Michael Pettis

{

"authors": [

"Michael Pettis"

],

"type": "other",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia"

],

"projects": [

"Eurasia in Transition"

],

"regions": [

"United States",

"China",

"Western Europe",

"North America",

"East Asia"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade"

]

}

Source: Getty

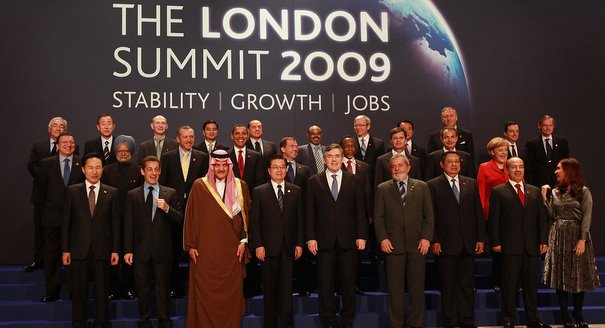

The G20 Meetings: No Common Framework, No Consensus

Until the United States, China, and the EU reach consensus about the roots of the global economic crisis and coordinate recovery policy, the world economy is likely to get worse before it gets better.

By failing to recognize the global implications of domestic recovery efforts, U.S. policy makers are risking increased trade friction and a longer downturn. The United States should coordinate better with China and the EU to keep trade open while the global economy adjusts to significantly reduced U.S. demand.

The April G20 meeting sidestepped the key issues dividing the United States, China, and the EU, who disagree fundamentally on the root causes of the crisis. Until the major powers reach consensus about the roots of the imbalance and coordinate policy to promote recovery, the world economy is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Key points for U.S. policy makers:

- China’s rapid growth depends on U.S. consumption, now rapidly declining. The stability of China’s political system rests, in large part, on the government’s ability to deliver strong growth. A deep, intractable recession could breed social unrest and aggravate nationalist tendencies.

- Asian economies have yet to feel the total impact of the crisis as the decline in U.S. consumer demand has not fully reverberated. The West must carefully manage the continued reduction in consumer spending to avoid sending Asian economies into an even more brutal tailspin.

- To prevent tit-for-tat protectionism, the United States and the EU should commit to coordinated stimuli to slow the decrease in Western demand for Chinese goods.

- China called for an alternate reserve currency because it believes the reserve status of the U.S. dollar—which allowed the United States to run almost limitless trade deficits—created the global trade imbalance. Chinese policy makers are deeply sensitive to any mention of China’s contributing role in the financial crisis.

Key points for Chinese policy makers:

- Beijing must commit to policies that boost domestic consumption directly, including liberalizing the domestic financial markets and interest rates, allowing greater worker autonomy in setting wages, raising the value of the currency, and taking steps to bolster the service sector.

- China’s stimulus plan increases exports rather than domestic demand, exacerbating the global imbalance.

- U.S. policy makers believe that policies aimed at encouraging production and suppressing domestic consumption—implemented by many Asian countries in the wake of the 1997 financial crisis—exacerbated the economic imbalances at the root of the current crisis.

Pettis concludes:

“With such fundamental disagreement among China, Europe, and the United States on the causes of the crisis, and with conflicting domestic policy needs, it is not surprising that the outcome of the G20 meeting was little more than a repeat of the 1933 London Conference. It is hard to see how the major powers can agree on anything substantial, what with the United States looking to craft an agreement on coordinated fiscal expansion but focusing so intently on domestic issues that it ignores the global context; with Europe reluctant to spend and far more concerned about re-regulating the global financial framework; and with China struggling to adapt its development model to a new world in which economic growth is no longer driven by out-of-control U.S. consumption.”

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie China

Michael Pettis is a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. An expert on China’s economy, Pettis is professor of finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, where he specializes in Chinese financial markets.

- What’s New about Involution?Commentary

- Using China’s Central Government Balance Sheet to “Clean up” Local Government Debt Is a Bad IdeaCommentary

Michael Pettis

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Other Global Crisis Stemming From the Strait of Hormuz’s BlockageCommentary

Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

- Shockwaves Across the GulfCommentary

The countries in the region are managing the fallout from Iranian strikes in a paradoxical way.

Angie Omar

- Taking the Pulse: Is France’s New Nuclear Doctrine Ambitious Enough?Commentary

French President Emmanuel Macron has unveiled his country’s new nuclear doctrine. Are the changes he has made enough to reassure France’s European partners in the current geopolitical context?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- The Iran War’s Dangerous Fallout for EuropeCommentary

The drone strike on the British air base in Akrotiri brings Europe’s proximity to the conflict in Iran into sharp relief. In the fog of war, old tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean risk being reignited, and regional stakeholders must avoid escalation.

Marc Pierini

- The U.S. Risks Much, but Gains Little, with IranCommentary

In an interview, Hassan Mneimneh discusses the ongoing conflict and the myriad miscalculations characterizing it.

Michael Young