When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

{

"authors": [

"John Judis"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

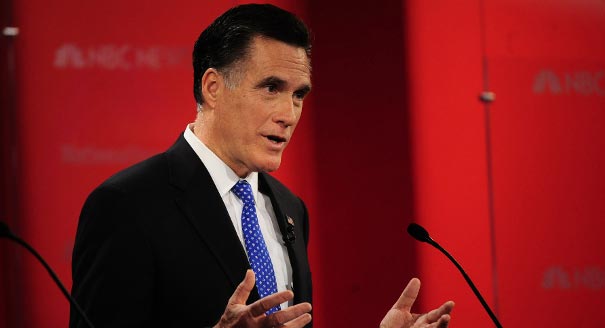

Following the first full-scale Republican presidential debate, Mitt Romney remains the most likely Republican nominee.

Source: New Republic

The first full-scale Republican presidential debate had to be a disappointment even to the most committed voters. Issues were rarely joined. The only candidates who looked like they could win the nomination and perhaps even be president were Romney and former Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty, but Pawlenty looked for the first hour like an actor from a community theater suddenly cast in a starring role on Broadway. If this debate and the recent Boston Globe poll is any indication, Romney is going to have to stumble badly not to win New Hampshire. And if he wins New Hampshire, he could be a good ways towards winning the nomination.

New Hampshire fits Romney’s candidacy. There is a vocal, but small religious right. In the 2008 Republican primary, Romney, John McCain, and Rudolph Giuliani—none of whom were favorites of the Christian right—amassed 80 percent of the vote. Pat Buchanan did win in 1996, but as an economic protest candidate. Republican voters will probably be overwhelmingly concerned with the economy and jobs. And the infusion of independents, who will not be distracted in 2012 by a competitive Democratic race, will probably pitch the electorate on economic issues somewhere to the center-right rather than the far right. In the Globe poll, a majority of likely Republican voters backed raising taxes on Americans making more than $250,000 a year.

If there is a social issue that stirs the New Hampshire voters, it is the kind of patriotism that McCain evoked in 2000 and 2008. In the Globe poll, likely Republican primary voters opposed cutting military spending by 58 to 38 percent and speeding up withdrawal from Afghanistan by 63 to 31 percent. Romney has tailored his own message to these voters. His announcement speech on June 2 in Stratham was a paean to “America’s greatness.” And in the debate, he distinguished himself from his rivals by opposing a quick withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Through the two hours, Romney generally seemed sure of himself. He only appeared peeved when he was asked twice about his opposition to the auto bailout and his prediction that it would mean the death of the auto industry. Romney supporters have told me that he will say almost anything on issues that he doesn’t care about, such as abortion or gay marriage, but that he is careful not to overstate his position on economic issues. That was apparent in the debate when the moderator pressed Romney for his position on the debt ceiling. Unlike Representative Michele Bachmann, who stated her willingness to vote no on the debt and everything else, Romney carefully put his position in conditional terms. Republicans should support raising the debt ceiling if Democrats agreed to spending cuts. He would not frame his response as a threat.

As a former governor, Pawlenty has some credibility as an economic policy-maker, but his pronouncements in the debate, like his earlier speech at the University of Chicago, seemed thin and somewhat vague. Perhaps the most interesting thing he said was that while he liked Paul Ryan’s budget, he would introduce his own Medicare plan. He became more eloquent in talking about God and religion and abortion. That will serve him well in Iowa, but not in New Hampshire.

It was difficult to take the other candidates seriously. Representative Ron Paul is back, but without his opposition to the Iraq war to win over younger voters. Now it’s mostly crackpot monetarism. (He wants to revive manufacturing in the United States by strengthening the dollar.) Bachmann likes to play up her role as a rightwing gadfly in the Republican congress, but she lacks Palin’s charm and sexual charisma. Gingrich looks like a grouchy Howdy Doody and is unlikely to last until New Hampshire, unless he plans like Alan Keyes to make a business of running for president. Santorum only stirs when God and sexuality beckon. And Herman Cain can be disarmingly candid—yes, we need food safety laws, he admitted (Bachmann and Paul would have said no), but we also need to screen Muslims very carefully before appointing them to government.

Romney, of course, has serious weaknesses as a general election candidate—like George H.W. Bush, he appears most at home with the country club set—and he will certainly have trouble convincing social conservatives in the South and parts of the Midwest to vote for him. As of this debate, however, he looks like he is in pretty good shape. Pawlenty will have to figure out how to operate on the big stage to challenge Romney. Or someone formidable will have to get into the race.

The Republican presidential primary electorate is not as rightwing and provocative as the mid-term electorate. It’s doubtful that the electorate could turn to the presidential equivalent of Christine O’Donnell or Sharon Angle. As a recent Fox poll revealed, 73 percent of Republicans nationally think it is “very important” that the Republicans nominate someone who can beat Obama, while only 53 percent thought it was “very important” that they agree with the nominee “on most major issues.” That’s a result that at this point has Romney’s name written all over it.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

And how they can respond.

Sophia Besch, Steve Feldstein, Stewart Patrick, …

They cannot return to the comforts of asymmetric reliance, dressed up as partnership.

Sophia Besch