While China’s economic strength is transforming its position in Asia, territorial disputes and other contentious issues are also shaping Beijing’s relations with its neighbors. In a Q&A, Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group, analyzes the global order and China’s changing role in Asia. Bremmer says Beijing prefers to focus on its bilateral relationships, but will increasingly need to work productively in multilateral settings as its influence grows.

- How is China’s global role changing? How is China’s role in Asia changing?

- How strong are China’s relations with its neighbors in Asia?

- What challenges does China face in Asia?

- Will China work multilaterally in agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership?

- What is the future dynamic of the Asia-Pacific region?

How is China’s global role changing? How is China’s role in Asia changing?

The global order will orient more and more toward China as its authority grows. With China becoming wealthier and soon taking over the title of the world’s largest economy, other countries will have no choice but to turn toward Beijing.

Asia will remain the most critical region for China (as well as for global growth) in upcoming years. Beijing’s reach goes basically everywhere in Asia, especially in Southeast and Northeast Asia. And China is the biggest economic player in the region.

But this doesn’t mean that the United States will be going away anytime soon. The United States and Japan are allies and this impacts China’s options. China and Japan are economic competitors and there are still significant security tensions between them. Given the importance of both Japan and the United States, China needs to maintain good relations with them and be especially careful to avoid conflict.

China also needs to do more to build trust with other countries in Asia. Not many countries in Asia trust China and the Chinese do not have an ideology that promotes the idea of kinship with its neighbors. This has compelled China to focus on developing strong bilateral relationships.

How strong are China’s relations with its neighbors in Asia?

China’s focus on developing bilateral relationships is exhibited by its extensive network of expat business communities in Asia. The success of these business communities, primarily in Northeast and Southeast Asia, has increased China’s economic influence throughout the region.

The significant Chinese business communities provide two-way channels for China’s leaders. Chinese business expats can supply on-the-ground insight of how these countries perceive China, while also providing informal means for Beijing to influence the decisions of other governments. And these strong economic ties work well with China’s preference for bilateral—rather than multilateral—relationships.

The strong presence of Chinese expats and significant Chinese investments in countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines have actually tempered tensions over territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

And, of course, there are other examples of China’s strong economic ties reducing tensions with its neighbors. China was almost at war with Taiwan at times over the last several decades, but now Beijing’s relationship with Taiwan is largely about how open mainland China is to Taiwanese inbound investment. And a million Taiwanese live in mainland China today, which provides a great market for the Taiwanese.

This is a strategy that China needs to continue to develop with countries that are of economic importance.

What challenges does China face in Asia?

China confronts several challenges in Asia. One significant security issue is its relationship with Japan. Unlike China’s relations with Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, and even Taiwan, there are virtually no Chinese doing business in Japan. It’s a black box for the Chinese. This poses a problem for China since Japan’s economy is much larger than the other countries and remains closely aligned with the United States.

But China’s main challenge in Asia is tempering its aggression on the security front. China’s heavy pushback on security issues has scared countries like Vietnam. While China has the advantage and is the dominant investor in Vietnam, its confrontational stance on territorial disputes in the South China Sea can be perceived as excessively aggressive. And this could cancel out the leverage China enjoys given its economic advantage.

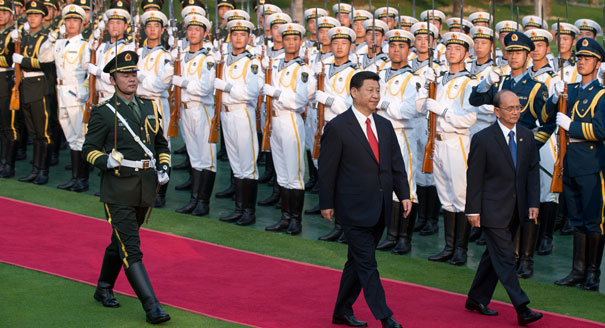

China’s investments in Myanmar also highlight the need for Beijing to be less aggressive. Currently, China is the dominant economic force in Myanmar, but it has been unwilling to give fairer treatment to locals when it comes to Chinese development projects. As a result, locals protested against the Chinese presence. If China does not address this issue a lot of Chinese businessmen will find themselves cut out as the Singaporeans, Japanese, and Thais start to enter Myanmar’s market.

In addition, China needs to address other economic and social issues, including the increasing ethnic tensions in Malaysia. There has been a growing call for a more pro-local Malay policy because the Chinese expat community has been seen as profiting at the expense of Malaysians. Still, Malaysia—or any other Asian country for that matter—does not want China out because the Chinese economy is too dominant. China retains the advantage in most of its economic relationships, but should be careful not to lose it through increased antagonism.

While Beijing is skilled at bilateral state-to-state relations, China’s ability to move beyond them is limited. China needs to be more involved, flexible, and act as a partner. This will require China to participate more at the multilateral level.

Will China work multilaterally in agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership?

The global order is reorienting toward multilateral coalitions, which can be dangerous for China given its focus on developing bilateral relationships. There will possibly be a dangerous backlash against the Chinese if they do not adapt their political and economic systems quickly enough.

In the present Asia-Pacific political environment, however, China is unlikely to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP is perceived as part of Washington’s “pivot to Asia” strategy, and with Japan’s involvement, China is unlikely to warm up to the TPP anytime soon. But multilateral coalitions could begin to form the counter to China’s bilateral standard in Asia and this could ultimately push China to join the TPP.

Over the long term the TPP could be seen from China in the same light as the World Trade Organization (WTO)—as China’s wealth increased, it actually sought WTO membership because it recognized the trade and economic benefits. Chinese membership in the TPP is contingent on several factors: that the TPP works, that China’s wealth continues to increase, that a cold war between China and the United States does not break out, and that China slowly adopts the rules and standards in keeping with the TPP mandate.

While this is the ideal, given its current political environment, China is not ready to join the TPP.

What is the future dynamic of the Asia-Pacific region?

In my recent book, I discuss the emergence of a G-Zero world where no single country or group of countries can provide consistent and successful global leadership. This dynamic will play out in Asia.

In Asia, the so-called pivot states, including Indonesia, Australia, Kazakhstan, and Singapore, are the most likely to do especially well in this environment. They are not overly reliant on major powers and can therefore use their relationships with bigger powers in their favor.

While it’s important for these countries to have positive relations with China, they are also able to pivot between China and other major economies. Singapore is a prime example. Singapore’s relationship with China is strong, but it still maintains good relationships with nearly every other country in Asia. Even pivot countries, however, will eventually be forced to mark their allegiances.

Other countries will suffer given their extremely close ties with China. This includes Mongolia, Laos, and Cambodia. Mongolia is a key country to watch. Even though it is rich in natural resources, the Chinese have essentially bought all of the significant resources. This has led to a backlash from the local Mongolians and the new Mongolian leadership is actually trying to limit the amount of Chinese investment coming in. But it’s too late—China already owns most of Mongolia.

China will need to adapt to this dynamic in Asia. However, change to any Chinese foreign policy will be incremental. Xi Jinping will be focused on expanding the social safety net within China first and China’s new leadership will likely be very cautious and risk averse for now.

The author is the president of Eurasia Group