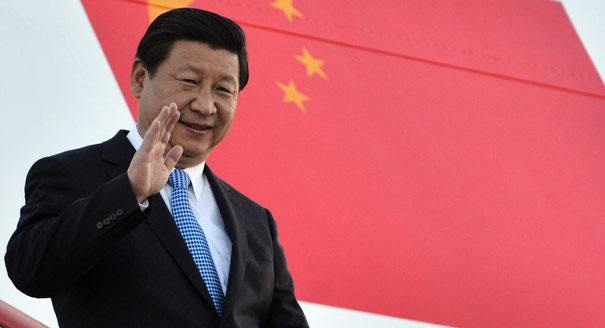

The new Chinese administration, led by President Xi Jinping, has made notable changes to the country’s foreign policy agenda. China has begun to play a more active, innovative role in international affairs and has adopted a new global perspective.

In a Q&A, Zhao Kejin explains that despite those changes, the core principles guiding the country’s foreign policy remain the same. Beijing’s primary goal of promoting a fair and peaceful international order informs all aspects of the country’s international relations and will shape the future of Chinese foreign policy.

- What are the primary aims of Chinese foreign policy?

- How has China’s international strategy changed since the new leadership assumed power?

- How is the global order changing? What does the new leadership see as China’s place in that order?

- Are U.S.-China relations likely to improve?

- Has China’s policy on North Korea changed with the new leadership?

- What role will developing countries play in China’s foreign policy?

- Do China’s military expansion and its increasing assertiveness on territorial disputes indicate that Beijing is adopting a more aggressive foreign policy?

What are the primary aims of Chinese foreign policy?

In its foreign policy, China seeks to achieve modernization, create a benevolent and peaceful external environment, and take steps that allow it to develop its domestic economy. To that end, the critical points of Chinese foreign policy are maintaining peaceful relations with other states and complying with the principles of fairness and justice.Beijing hopes to build momentum for its domestic development through its external activities, including securing resources overseas. The Chinese government contends that diplomacy should ensure the country’s prosperity, open up new paths for the nation’s rejuvenation, and create conditions that benefit the Chinese people.

How has China’s international strategy changed since the new leadership assumed power?

Since Xi came to power, China has become a more aware, involved international actor and is pursuing innovative initiatives with the hope of becoming a new sort of great power. In general, there have been three big changes in China’s foreign policy.

First, instead of looking at issues from a China-centric perspective, Beijing now looks at issues from a more global angle, using international trends to inform its external relations.

Second, China is now more aware of and takes more initiative on issues of global importance. Beijing is increasingly willing to assume responsibility on these matters.

Third, China is placing greater emphasis on innovation and awareness. This is demonstrated by its focus on new initiatives, such as first-lady diplomacy and increased communication with neighboring countries, and by its determination to pursue what Xi has called “a new type of great-power relationship” with the United States.

On June 27 at the 2013 World Peace Forum in Beijing, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China had to become a great power and pursue great-power relations but that it should not do so in the mold of previous great powers. This means that China will not tolerate interference from foreign forces in its diplomatic decisions and will not seek alliances or hegemony. Instead, Beijing will pursue a path of peaceful development.

How is the global order changing? What does the new leadership see as China’s place in that order?

Today’s international system is based on multilayered, multidimensional networks. Whether it is an enterprise, a country, or a person, no single entity can exist in the world without a network.

This new order means that great-power relationships are no longer between countries but rather between networks. If these different networks are allowed to interact, eventually a consensus and a sense of community will emerge, as happened with the European Union. The network will progress into an interconnected system in which each stakeholder has mutual interests, and there will no longer be divisive viewpoints.

China is in the process of finding its place in this new world order and seeking its own competitive advantage. Beijing has begun strengthening its networks, including ones in which the United States does not participate, such as in the association of developing countries known as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership between China and ASEAN.

Moreover, China has actively promoted reforms in global organizations such as the IMF, the World Bank, and the UN. The premise of these reforms is that China prioritizes sustainable domestic development first and external affairs second.

Are U.S.-China relations likely to improve?

The core of the U.S.-China relationship has long been competition, and Washington will not abandon competing with Beijing. China, however, has decided that the key to its future is not to fight a war with the United States—and certainly not to claim U.S. turf—but instead to establish better relations between the two countries so that China can develop itself and create the necessary conditions for peace.

I am cautiously optimistic about the prospects of Beijing realizing this goal and the United States and China establishing a new type of great-power relationship. There is cause for hope in that the long-term future of this relationship will be decided by the people, and the Chinese and American people want the same thing: to live in peace and prosperity. Given the increasing bilateral connections between China and the United States, there will be more and more issues of mutual interest.

However, I am cautious because there are always those on both sides that want competition and confrontation, as their thinking remains rooted in Cold War ideology. There are also contradictions and frictions as well as profound disagreements on values and interests between the two countries that could potentially lead to difficulties in the bilateral relationship.

Both sides will need to make concerted efforts to avoid these potential pitfalls and establish a more productive relationship, such as reducing political interference in U.S.-China relations and instead letting market forces rule the relationship. The United States should abandon its discriminative economic policy toward China, which has not changed since the Cold War, and both countries should allow market forces to decide the fate of their economic cooperation.

In addition, the United States and China should strengthen bilateral communication and contact at all levels, from heads of state to specific government departments and civil society actors. This increased interaction will allow the U.S. and Chinese governments to form a consensus. It will also establish a risk management mechanism to not only reduce points of friction but also develop understanding between the two countries as well as a way to manage crises and prevent tensions from escalating.

The two countries will need to respect each other’s core interests and avoid challenging each other’s bottom lines on these issues. For China, these interests are Taiwan, the South China Sea, Tibet, Xinjiang, and the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands territorial dispute. This also means that China must not challenge the United States’ position as the global leader, and the United States must not challenge the ruling position of the Chinese Communist Party.

Has China’s policy on North Korea changed with the new leadership?

Under the Xi administration, China has shifted its North Korea policy from one meant to preserve the “traditional China–North Korea friendship” to one that promotes China’s foreign policy goal of advancing a peaceful and stable order. Accordingly, China is now more willing to criticize North Korea when Pyongyang takes steps to undermine this order.

The present Chinese policy is about advancing principles, including the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, the resolution of disputes through dialogue and consultation, and the maintenance of peace and stability in the region. China will support any policies that adhere to these principles and oppose any that challenge them.

This shift is a reflection of Xi’s commitment to creating a peaceful, just international system and of the fact that China will not allow North Korea to challenge this order.

What role will developing countries play in China’s foreign policy?

Developing countries will be a cornerstone of China’s foreign policy under Xi. Developing countries and emerging powers are China’s reliable friends and sincere partners. While not forgetting its old friends, China must actively expand its development of new partnerships. These relationships support China’s overseas interests and investments but are not motivated by strategic concerns.

Xi’s first trip after assuming power was to Russia, which indicates that Beijing prioritizes emerging countries, as China is one itself. This visit also testifies to China’s emphasis on great-power relationships.

The trip aroused speculation that China was seeking to unite with Russia against the United States, but these accusations are baseless. Beijing prioritizes its relationship with Moscow for a very practical reason: China shares a longer border with Russia than with any other neighboring country. There was not a single indication that the Chinese president visited Moscow for strategic reasons.

Likewise, there have been accusations that Xi’s recent visits to Latin America are part of a strategic plan to undermine U.S. hegemony in the region. In reality, these visits have no strategic significance or considerations whatsoever. They represent comprehensive global diplomacy intended to establish a new, more balanced type of development relationship among partners. They are certainly not aimed at containing the United States.

Do China’s military expansion and its increasing assertiveness on territorial disputes indicate that Beijing is adopting a more aggressive foreign policy?

China’s military expansion is a necessity born of its rapid economic development, which has given it many interests to protect. It is not for the purpose of aggression.

China is not threatening other countries. On the contrary, it has good relationships with nearly all its neighbors (except for Japan and the Philippines, with which it has territorial disputes).

China only began having trouble on territorial matters after the U.S. pivot to Asia because the United States is attempting to undermine Beijing. Washington exaggerates Chinese aggressiveness and uses China as an imaginary threat to enhance the power of its alliances and provide an excuse for U.S. arms sales.

The power to shape contemporary global discourse is in the hands of the United States, but China will not simply give up its territorial interests. Although Beijing seeks peaceful development, it is China’s legitimate right to respond to any external provocation that it deems threatening to its national security.

This article was published as part of the Window into China series