Source: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

I became acquainted with Secretary McNamara in the mid- 1990s when I helped organize a series of Track II dialogues between Americans and Indians and Pakistanis. This was before India and Pakistan became overt nuclear-armed states with their tests in 1998. In these dialogues the aim was to discuss with influential Indians and Pakistanis – former generals, foreign secretaries, and the like – the risks and burdens that arise from nuclear-armed competition. No one had wrestled so hard and openly with these challenges as Robert McNamara. He had done so while serving as Secretary of Defense during and after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then in the decades following his government service. Thus, we were honored and moved that he would volunteer his time and subject his body to the wear and tear of travel to South Asia to share his experiences and perspectives.

By the mid-1990s when we were conducting our dialogues in South Asia, the Cold War was over. McNamara had even earlier concluded that the military utility of nuclear weapons was a dangerous illusion. He had come to this view in large part through the Cuban Missile Crisis and the subsequent attempt he led to develop a strategy of “flexible response.” That strategy – which has bearing on Indo-Pak relations today as I will elaborate – was McNamara’s and NATO’s answer to the problem posed by the apparent superiority of Warsaw Pact conventional forces over those of NATO. McNamara’s team had concluded that NATO could not simply rely on massive nuclear retaliation to deter Soviet conventional aggression – this would not be credible. Instead, NATO needed to develop more symmetrical means to deter or fight Warsaw Pact conventional forces.Thus, Flexible Response called for NATO to expand its conventional military forces and diversify its theater nuclear forces so that NATO could “counter an attack at whatever level the aggressor chose to fight.”1 U.S. strategic nuclear forces, designed to attack the Soviet homeland, would be held in reserve as the ultimate deterrent (but also at the ultimate cost, as retaliatory strikes on the U.S. would be inevitable).

Yet, as McNamara later acknowledged, Flexible Response was never really operationalized. NATO did not build the envisioned conventional capabilities. The problem of asymmetry did not go away for the U.S. until the Soviet Union collapsed and the Cold War ended.2

India and Pakistan are now wrestling with problems like those posed by the perceived asymmetry in NATO and Warsaw Pact military capabilities. Indeed, for years observers of the South Asian scene have said that Pakistan is struggling with security threats similar to those that NATO faced in the Cold War, and so, naturally, Pakistan must rely increasingly on nuclear weapons to offset India’s growing conventional power, much as NATO did to balance the Warsaw Pact. (Pakistani elites do not discourage these comparisons.)

But such comparisons are both misleading and incomplete. What is misleading – and I mean misleading in effect, not intention – is that the asymmetries between India and Pakistan are much more complicated than those that confronted the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The South Asian asymmetries exist at the level of overall power, and nuclear and conventional capabilities, and the policies that India and Pakistan use to impose their will on each other. Indeed, the structure of the relationship between India and Pakistan creates unprecedented complexities and difficulties as I will explore later.

What is incomplete in analogies between the predicaments of NATO and Pakistan is that NATO’s answer to asymmetry – flexible response – was chimeric, not something to be relied upon. As McNamara later acknowledged, even if Flexible Response had been resourced fully, the problem of confining potential use of nuclear weapons to the tactical level in the Central European theatre was impossible to solve with an abiding degree of confidence. This was the central point McNamara made during discussions in South Asia. NATO and the Warsaw Pact just lived fitfully under a cloud of insecurity until the Soviet Union collapsed from its own internal failures and fissures and the Warsaw Pact dissolved.

Tonight I want to very briefly describe the cloud of insecurity and potential nuclear war that darkens the horizon between Pakistan and India. Then I will summarize what I think are the five unprecedented structural features that produce the risks of conflict and that seriously complicate efforts to mitigate them. These structural characteristics are important for scholars to analyze and necessary for policy-makers to understand in trying to redress them. In the third part, I will explore five options that India – as the defender – could consider to induce Pakistani authorities to decisively turn against the use of asymmetric force against India. All of this, of course, has implications for U.S. policy. For, the U.S. is the outside power that has been and will be most likely to intervene to de-escalate potential crises between India and Pakistan. My hope is that we can discuss U.S. policy options in the Q and A.

Historical Background

The history of Indo-Pak competition is fascinating and intricate. Time allows only the shortest summary here tonight. I skip over partition and three wars – in 1948, 1965, and 1971 -- and begin with the nuclear tests that India and Pakistan conducted in May 1998.

After the nuclear tests a hopeful peace process was launched in February, 1999. It was aborted months later when the Pakistani Army secretly – under the guidance of Pervez Musharraf -- infiltrated “irregular” forces to occupy high-peaks in the Kargil region of Kashmir that had been held previously by India. This led to the Kargil Conflict, in which at least 1,000 military personnel from both sides were killed, and thousands more wounded. Indians drew the frightful – to them – conclusion that Pakistani Army leaders now felt that nuclear deterrence would give Pakistan a free hand to undertake small-scale violence against India, believing that India would not use its conventional military power to retaliate against the Pakistani heartland, because doing so could trigger nuclear war.

While Indians were still wrestling with the lessons from the Kargil conflict, in December 2001, terrorists associated with two Pakistani militant organizations attacked the Indian Parliament in New Delhi. This prompted India to undertake a massive mobilization of 500,000 troops toward the border with Pakistan. The ensuing crisis lasted nearly two years. India sought to compel Pakistan – now led by President General Pervez Musharraf – to disband the jihadi/terrorist organizations involved in this attack and to disavow the use of proxy or terrorist violence against India. Musharraf made intermittent efforts to this end -- under pressure from the U.S. too -- which helped modulate the crisis.

But the Pakistani crackdown on militant groups was never fulsome. Pakistan’s motivations were attenuated in April 2002 when devastating riots erupted in the Indian state of Gujarat, leaving more than 1,000 Muslims dead. The Indian state government – led by Narendra Modi who now seeks to be prime minister of India -- was either complicit or at least feckless in trying to stop the carnage. A month later, the most potent militant group in Pakistan, the Lashkar-e-Taiba attacked on Indian Army campy in Jammu, killing thirty-six people, including wives and children of Army personnel.

This crisis wound down by late 2002, and shortly thereafter the two states began a secret, back-channel dialogue to try to find ways to resolve the Kashmir issue.

Meanwhile, the Indian Army, in 2004, announced a new military strategy that it called “Cold Start.” This was their answer to Kargil and the 2001 terrorist attack. Rather than spend months mobilizing massive armored formations for major attack deep into Pakistan, the new plans called for creating smaller highly-mobile units with supplies pre-deployed at positions close to Pakistan, so that Indian forces could attack within three days’ of authorization. The attacks would be at multiple points to challenge Pakistan’s defensive planning and deployments. Importantly, the scale of the Indian forces would allow them only to take small slivers of Pakistani territory. Indians thought or hoped that the limited scope of the planned operations would stay below the threshold that would cause Pakistan to use nuclear weapons.

The idea of Cold Start still has not been translated into real military capabilities, but the idea itself has been enough to drive the Pakistani Army to seek a counter. Their answer has become clear in the past three years. It is to develop battlefield nuclear weapons. If the Indians want “Cold Start,” Pakistani wits say, then we will give them “Hot End.”

In any case, through the mid-2000s, while the Indian and Pakistani militaries prepared for the worst, the back-channel diplomacy proceeded and made some progress. Pakistan continued to be plagued by internal violence. Extremist groups grew and proliferated, not only along the Afghan border but also in the Punjabi heartland. Yet, no major terrorist attacks were projected from Pakistan into India. Meanwhile, President Musharraf’s power began to plummet in 2007, and with it his capacity to turn the back channel peace process into an official breakthrough. In 2008 he left the country.

Then came the Mumbai attack, on November 26, 2008. Ten Pakistani terrorists rampaged through two luxury hotels, a Jewish center, and the Railway station in Mumbai, killing 164 and wounding more than 300 others. India, notwithstanding the Army’s earlier declaration of the Cold Start strategy, did not respond militarily. As Prime Minister Manmohan Singh reportedly said in private, “this is the cost of living in this neighborhood.” It would be self-defeating for India to divert its energies from the strategic priority of developing the economy.

The televised horror of the Mumbai assault and the clear evidence that the perpetrators had been trained and orchestrated in Pakistan led to immediate global condemnation of Pakistan, and caused considerable embarrassment and humiliation for many Pakistanis who were sickened by what they saw.

I sketch this history simply to give you a picture of the challenges facing those in India and Pakistan who seek to prevent war or manage it if it comes. The war starts with dramatic terroristic violence in India conducted by individuals and groups emanating from Pakistan, with plausible ties to elements in the Pakistani intelligence services. The Indian state then faces enormous emotional and political pressures to respond militarily to inflict enough pain to compel the Pakistani Army and intelligence services finally to curtail such proxy violence and eradicate the groups that perpetrate it. However, if the forces India would develop and deploy were actually as effective as they are intended to be in penetrating into Pakistan, they could prompt Pakistan to use nuclear weapons to stave off such defeat.

Meanwhile, efforts to negotiate peace between the two countries, often behind the scenes, create incentives for extremists -- and perhaps some in the Pakistani security establishment who prefer neither peace-nor-war -- to create crises by conducting low-level attacks against India. And Indian bitterness over unpunished terrorism leaves New Delhi leaders loathe to make magnanimous offers to Pakistan.

We can say many things about this dynamic, but one of them is that no other nuclear-armed competitors have faced risks of war as direct, proximate, and complicated.

Five Structural Characteristics of the Challenge

The episodes recounted above point to at least five structural factors that combine to make the nuclear dynamic between India and Pakistan unique among all nuclear-armed states.

Most broadly, these two states operate in a strategically competitive triangle that includes China. India strives to develop nuclear weapons, missiles, and other platforms to achieve a strategic deterrent against China, whose strategic capabilities are growing. India also figures China’s assistance to Pakistan in assessing the threats it faces. Pakistan calibrates its nuclear and related requirements against the capabilities it projects that India – trying to balance China -- will acquire over coming decades.

This southern Asia triangle is connected to another triangle comprised of the U.S., Russia and China. China develops strategic capabilities in competition with the U.S. – nuclear weapons, missiles for conventional and nuclear missions, submarines, anti-satellite systems, etc. The U.S. develops capabilities in anticipation of what China is doing. Russia reacts to both.

Further connecting the two triangles, U.S.-Indian cooperation alarms China and Pakistan. So, Pakistan is frustrated that it cannot control how the U.S. may augment India’s nuclear and conventional capabilities. And India is frustrated that it cannot control China’s assistance to Pakistan.

No such complicated, multi-directional dynamics affect nuclear-armed states other than India and Pakistan.

The second structural factor is India’s inherent superiority in overall power. In human and economic resources which can be transformed into coercive the two countries, over time, simply will not be evenly matched. This drives Pakistan to seek asymmetric strategies to deter and/or compel India.

Here arises the third pertinent structural condition: Pakistan, faced with India’s growing conventional capabilities, has relied on asymmetric counters in the form of sub-conventional aggression (terrorism and insurgency in Kashmir). This is augmented now by a commitment to build battlefield nuclear weapons.

Thus, the structure or spectrum of conflict (and/or deterrence) between Pakistan and India runs from the sub-conventional to conventional to nuclear, and is asymmetric at each level.3 To say this another way, deterring Pakistan or India from initiating major conventional war against each other is over-determined at this point in history. Both governments and populations know they cannot achieve any policy objective through initiating a big war. So, too, there is no problem deterring the Pakistani state from launching a bolt-from-the-blue nuclear attack on India. The challenges are preventing subconventional aggression and the asymmetric escalatory process that it could trigger.

This points to the fourth structural condition, also unique: Pakistan is home to violent groups recruited and trained to project terrorist violence into India.4 The most effective of these groups, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba, originally were nurtured by Pakistani agencies. At the very least, Pakistani authorities have not tried seriously to dismantle them. The operation of militant organizations dedicated to attacking India raises portentous questions about the monopoly and unity of state authority over the projection of violence from Pakistani territory.

Deterrence theory generally assumes that states operate as unitary rational actors. To be sure, complex systems such as states are often riven by competing organizations, interest groups and personalities. Thus, the internal dynamics within “normal” states mean that the unitary rational actor model is an ideal type, rather than a descriptive reality. Still, when it comes to functions as portentous and centrally controlled as initiating and managing warfare between nuclear-armed states, it is generally assumed that a tight, coherent line of authority operates in ways approximately consistent with the unitary model. The implications for deterrence stability are profound if a state is not functioning as a unitary actor, or claims not to be when it is convenient, or is not perceived to be by those who seek to deter it.

If a terrorist attack happens, India would feel enormous pressure to retaliate militarily to impose a cost on Pakistan (and to satisfy Indian desire for revenge). India would simultaneously seek to compel the Pakistani state to eradicate the terrorist groups and to deter the Pakistani military from escalating the conflict by using nuclear weapons to counter India’s conventional military operations.

India’s management of this combined compellence-deterrence strategy would be challenged enormously by the uncertain structure of Pakistani authority over anti-Indian terrorists. For example, while India could perceive that the terrorist attacks it attributes to Pakistan signal Pakistani aggressiveness, Pakistani leaders could perceive the initial terrorist attacks as a reflection that the Pakistani state is merely unable to stop aggrieved citizens from compelling India to make political accommodations in Kashmir or more broadly. If Pakistani leaders did not authorize the terrorist attack on India, and India retaliated militarily, the Pakistani leaders would feel that India was the aggressor, and Pakistan the aggrieved defender. In normal models of compellence and deterrence, the defender is more motivated to run risks, including the use of nuclear weapons, against an aggressor who is attacking its territory.

On the other hand, Indians are aware that Pakistani authorities have incentives to claim they have no control over the terrorists who attack India. By not holding the Pakistani state responsible, India would give Pakistan a free pass to facilitate or at least do nothing to stop terrorists from attacking. So, under the logic of deterrence and compellence, India feels itself to be the aggrieved defender and is motivated to hold the Pakistani state accountable for terrorism that emanates from Pakistani territory.

You see that when the unitariness of state control over instruments of violence is ambiguous, as in Pakistan, it is possible for both antagonists to feel they are the righteous defender. Both may feel that the leadership of the other is firmly in control and creating false pretexts to obscure its aggressiveness. Both can feel that the other is escalating disproportionately, which in turn fuels escalation. In short, the room for misperception and therefore miscalculation grows enormously.

The fifth structural factor in the Indo-Pak competition is the two states’ (generally tacit) reliance on outside powers, especially the United States, to intervene diplomatically to prevent a crisis or low-level conflict from escalating. This could be seen in the Kargil conflict, the 2002 crisis, the 2008 crisis, and the logic of Cold Start.

Groping For Solutions

Pakistan and India are groping for solutions to these structural challenges which no other nuclear-armed competitors have ever faced. These challenges afflict both states.

The ideal situation would be if Pakistan were to take actions to demonstrate that it no longer seeks directly or through proxies to “liberate” territory now controlled by India. Of course, persuading Pakistani leaders to demobilize anti-India jihadi groups will be extremely difficult without a tolerably “fair” resolution of the Kashmir issue. Even with confidence-building diplomacy over Kashmir, Sir Creek and Siachen, it would take significant time and effort for India to convince Pakistanis that its intentions are purely defensive. Yet, because India’s core interests really are not offensive vis a vis Pakistan the basis exists for eventually persuading Pakistan that it does not need to retain “irregular” forces to fight India.

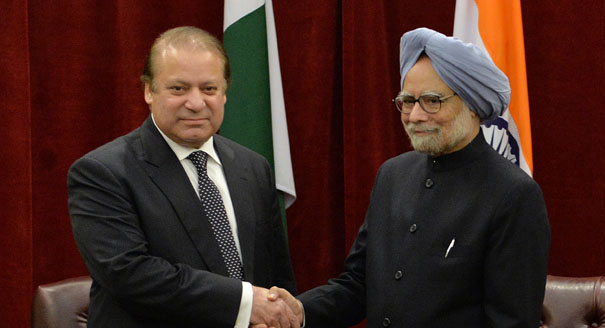

There are some signs that the Pakistani leadership recognizes that further terrorist attacks against India are not in Pakistan’s interest. As a former director general of the ISI put it in a recent conversation, “have you noticed that there has not been an attack on India since Mumbai in 2008? Don’t you think this means something?” The same retired general noted that in the 2013 Pakistani election campaign no party ran on anti-India positions. Indeed, Nawaz Sharif, whose margin of victory was surprisingly great, campaigned that he was best equipped to improve relations with India. A new Army doctrine adopted at the end of 2012 identified internal militancy as the “biggest threat” to Pakistani national security. Army Chief of Staff General Kayani has called for Pakistanis to fight a “war on extremism and terrorism,” which he termed a “just war.”

The question is whether Pakistan’s turn against militancy will extend to groups that concentrate their violence against India, not the Pakistani state. In the discussion period, if you like, we can get into how challenging this truly would be for Pakistan to do.

But the Pakistani Army and ISI will be less likely to demobilize the anti-Indian “reserves” if India continues under a “proactive” strategy to augment the conventional military forces it deploys against Pakistan. The circularity of this problem is apparent. As a result of all this, it is reasonable to think that we are some time away from defusing the terrorist (or subconventional) trigger of Indo-Pak war. Thus, India will continue to consider what options it should pursue to compel and/or deter Pakistan from tolerating or facilitating violence against India.

India could consider five basic options. They are presented here in simplistic form, recognizing that each would require detailed evaluation.

Option 1: Reinforce Cold Start

One option is to continue the logic of Cold Start and seek ever greater conventional military capabilities to punish and/or deter Pakistan. Recently, Indian analysts and leaders have questioned the strategic wisdom of threatening multi-pronged rapid Army incursions into Pakistan if that would prompt Pakistan to use battlefield nuclear weapons. Yet, Indian decision-makers could conclude that seeking clear Army-centric superiority is the right strategy, but that the problem has been the too-slow acquisition of the requisite forces and operational acumen. In this view, doubling down on capabilities to invade Pakistan and humiliate its Army could motivate Pakistani decision makers finally to do everything in their power to curtail terrorism.

However, multiple factors militate against this asymmetric option. Practically, materially, bureaucratically…India is having a very hard time implementing anything like the military magic of Cold Start.

But more importantly, the strategy itself is flawed. The core problem stems from the objective of putting Indian boots on Pakistani territory in response to anything less than a major conventional aggression by Pakistan. If Indian forces succeeded well enough to defeat the Pakistani Army and occupy slices of Pakistani territory, then how would that Army and the ISI have the will and capability to more effectively counter the most formidable anti-Indian terrorist groups in Pakistan? The Army and the ISI would seem to be necessary instruments in dismantling or at least compelling groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba to abandon terrorism against India, but would they be willing and able to do so after being defeated by India?5

Presumably, India’s leverage to compel Pakistan would stem from the armed occupation of some Pakistani territory, albeit of a limited scope. (“If you want your land back, do what we tell you to.”) But how long could the Indian forces remain before they would experience the challenges that much better equipped U.S. and NATO forces experienced on Iraqi and Afghan territory? Would not the presence of Indian troops on Pakistani soil spur recruitment of militants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere to fight the occupiers and mount terrorism attacks in Kashmir and the Indian mainland?

At the very least, militant groups and their sympathizers would become more motivated to resist efforts by Pakistani leaders to tame them. Indeed, groups that practice terrorism often seek to provoke the adversary to over-react, in order to intensify their members’ commitment and rally the wider nation to the justness of their cause.

An Army-centric strategy to put Indian boots on Pakistani ground also bumps against the central effect of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons have proved relatively useless for compellence, for defeating insurgencies, and for deterring terrorism.6 Their real value is to deter other states from committing aggression into your territory on a scale that threatens existential interests. An Indian strategy that centers on moving troops and armor into Pakistani territory invites a relatively credible threat of Pakistani nuclear retaliation against those forces, placing the burden of the next escalatory move onto India.7 Pakistan could use nuclear weapons only on its own territory, to destroy the invaders and avoid defeat at their hands. India then would face the huge escalatory risk of deciding whether to be the one to make nuclear strikes across the border, knowing that this could likely prompt Pakistani nuclear retaliation on Indian cities. Provoking nuclear exchanges would be excessively disproportional to the stakes created by the original terrorist attack on India. This would make the threat to do so either not credible, or extremely unwise, or both. Moreover, India has a strong interest in reducing the salience of nuclear weapons in Indo-Pak relations. An Army-centric strategy like Cold Start would have the opposite effect, notwithstanding Indian intentions.

The core reality that Cold Start neglects is that India does not want to acquire or occupy any territory now controlled by Pakistan. This reality is the basis for hope that Pakistan could conclude that it can live at peace with India. A strategy whose success posits such occupation, even on a limited scale and for a limited time, hardly seems in India’s interest.

Option 2: Symmetric Counter-Terrorist Strikes

Recognizing the liabilities of an Army-centric strategy to compel a nuclear-armed neighbor to abandon terrorism, India could consider a different option that would be more proportional, precise, and credible. Such an option would consist of punitive air-borne strikes on the organizations and, if possible, individuals responsible for conducting and facilitating the terror attack(s) on India. Striking perpetrators rather than invading Pakistan with ground forces would avoid most of the liabilities of an Army-centric strategy.8

The huge problem with this option, of course, is capabilities. India lags far behind the United States and Israel in acquiring the intelligence, reconnaissance, and precision-strike systems that are necessary to locate and kill terrorist targets from the air (via missiles and manned and un-manned aircraft). This is one reason why the Cold Start concept emerged in the first place. (Another reason is the institutional and cultural dominance of Armies and Army-thinking in India and Pakistan).

Even if India did acquire the intelligence means to identify Lashkar-e-Taiba and other groups’ training camps in Pakistan and the missiles and precision-guided bombs to hit such fixed targets accurately, many of the facilities that would be most easily targeted would be co-located with non-combatants. Strikes against such targets could create counter-productive effects such as media images of innocent victims or of bombed structures that were empty at the time of attack, leaving the targeted terrorists unscathed.

Furthermore, how would India reassure Pakistan that the incoming missiles or aircraft are not carrying nuclear weapons? The risks of miscalculation and over-reaction would not be insignificant.

Finally, a stand-off counter-terrorism strategy would be Pakistan-specific. Yet, India now benchmarks its military plans and requirements against both China and Pakistan. Thus, it is far from clear whether Indian leaders, defense policy-makers, and military would find it desirable and/or feasible to tailor two demanding and expensive strategies and capabilities – one for Pakistan and one for China. This is a central challenge of the triangular structure of India’s security relations with Pakistan and China.

Option 3: Foment Insurgency in Pakistan

There is an alternative symmetrical option: India could counter future sub-conventional “aggression” from Pakistan with similar Indian support for insurgent groups contesting the Pakistani state. This form of symmetric retaliation would not pose the technical and economic challenges to India that a strategy of precise, stand-off punitive attacks would. The symmetry could reduce the risks of escalation to major warfare, while at the same time imposing a physical cost on Pakistan for its perceived unwillingness to combat anti-Indian terrorism.

However, a symmetrical sub-conventional strategy would not serve Indian interests. India would need to keep its support for Pakistani insurgents/terrorists secret. India would be stooping to the morally and legally low level of behavior it condemns Pakistan for practicing. The need for secrecy would deprive the government in New Delhi the means to satisfy its public (and opposition) that it was acting robustly against the presumed Pakistani offense. Moreover – strategically-- helping violent groups in Pakistan would make Pakistan still less governable and more violent than it is today. Yet, India’s long-term interest is for Pakistan to be better governed, less violent, and more prosperous. For these and other reasons, then, Indian leaders would be wise to eschew temptations to pursue sub-conventional violence against Pakistan.

Option 4: Develop Battlefield Nuclear Weapons

A fourth option would be to symmetrically counter Pakistan’s plans to develop and deploy battlefield nuclear weapons. Pursuing battlefield nuclear weapons would not substitute for any of the prior options, but would complement them. The objective – a la Flexible Response -- would be to seek escalation dominance by deterring Pakistan from using battlefield nuclear weapons in response to Indian use of force after a terrorist attack. The most likely scenario would be if India conducted an Army-centric military campaign a la Cold Start.

Indian strategists and politicians have long decried battlefield nuclear weapons – whether in Europe or on the subcontinent. Indians have argued that the notion of limiting nuclear use to the battlefield is delusional because escalation would be inevitable. They argue that in a nuclearized environment the only rational policy is to foreswear first use of any nuclear weapons. If Pakistan or another adversary does not recognize this imperative, they will create an existential threat to India which India would meet with massive retaliation. Thus, in April 2013, the chairman of India’s National Security Advisory Board, Shyam Saran gave a semi-official response to concerns that India’s nuclear doctrine and capabilities were not adequate to address Pakistan’s development of battlefield nuclear weapons. Saran said that “if India is attacked” by nuclear weapons of any kind “it would engage in nuclear retaliation which will be massive.”9

However, just as McNamara and the Kennedy administration found that the doctrine of massive retaliation lacked credibility, Indian strategists eventually may also conclude that threatening massive nuclear retaliation in response to limited Pakistani use of nuclear weapons on invading Indian military forces may appear too disproportional and undiscriminating. It would be more credible on all counts to develop nuclear weapons with ranges, yields, and targeting doctrine to threaten Pakistani conventional forces, while retaining massive retaliation options to deter further escalation.10 There are technical issues here, of course. Could India develop a more flexible nuclear arsenal like this without further explosive testing? How long it would take? How much it would cost?

In any case, India’s political leaders are likely to prefer (at least privately) to seek a less militarized modus vivendi with Pakistan that would dissuade Rawalpindi from deploying battlefield nuclear weapons. However, if terrorist threats from Pakistan go unchecked, and India pursues an asymmetric, proactive Army-centric strategy like Cold Start in response, Pakistan will not eschew battlefield nuclear weapons. Eventually, then, pressure will mount in India to develop symmetric counters. This leads to the dilemmas of Flexible Response which McNamara could never resolve.

Option 5: Non-violent Coercion

The fifth option is in some ways the least orthodox, although it is consistent with Indian practice since the movement to achieve independence from the British empire. India could explicitly pursue a strategy of competitive restraint, or non-violent leverage. Instead of responding to Pakistan-sourced terrorist attack with major conventional military operations on Pakistani territory, and then preparing to match Pakistan up the escalation ladder, India could hold fire and mobilize Pakistani society and international organizations against the Pakistani military-intelligence establishment that has not done enough to end anti-India terrorism.

Such a strategy would recognize that India’s core interest is to see Pakistan become less violent, better governed, and more vested in peaceful economic cooperation with India. The Pakistani Army and ISI traditionally have impeded Pakistan from evolving in this way, largely by projecting India as an aggressor that would destroy the country if it were not for the resolve and skill of a well-resourced Army. Yet, recent political-economic developments in Pakistan demonstrate that a majority of Pakistanis question the Army’s obsession on India. This majority clearly does not support terrorism against India.

Indian restraint in the face of another such attack with links to Pakistani state agencies would deprive the Army of a rallying opportunity and instead leave it further exposed as a source of danger and embarrassment to many Pakistanis. If international outrage and moral-economic sanction could be mobilized against Pakistan – in lieu of war which would carry the risks to India mentioned above – such pressure would further the prospects of Pakistan’s evolution toward the sort of state that India ultimately would prefer to live next to.

Of course, competitive restraint or non-violent coercion would not be instinctively satisfying and would be politically difficult to execute. The “normal” strategy would be to respond to violence with violence. India rightfully seeks to be recognized as a major power. Great powers hit back, national security experts will say. Yet, if the experiences of the ultimate great power – the U.S. -- in Iraq and Afghanistan are instructive, Indian decision-makers would be wise to consider more subtle and sustainable approaches that are more fitting to the threat.

To their credit, some Indian leaders, including Prime Ministers Vajpayee and Singh, have understood the relative wisdom of military self-restraint in the face of terror attack. They have understood that violence, in the words of Hannah Arendt, “like all action, changes the world, but the most probable change is a more violent world.”11 Moreover, subconventional aggression is different from conventional war or nuclear attack. Responding disproportionately to it is likely to be self-defeating, even if your army wins its battles. In the words of former Indian foreign secretary Lalit Mansingh, following the Mumbai attack, “There is no military option.” Instead, as Steve Coll reported, Mansingh said India had to “isolate the terrorist elements” in Pakistan, not “rally the nation around them.”12

If this is correct – and I think it is – then the great challenge for Indian leaders and opinion shapers is to cultivate public support in advance for such a strategy. This political-strategic effort could be augmented by building support in advance in the United States, the European Union, the G-20, and the United Nations to bring Pakistan to account if its agencies are found negligent in preventing future terrorist attacks on India. UN Security Council Resolution 1373, passed after the 9/11 attacks, obligates all states to take actions to prevent and suppress terrorists’ efforts to recruit, organize, train, fund-raise and carry out attacks. This is a Chapter VII resolution. Pakistan – clearly – in the past has not met the requirements of this resolution, but has been protected by China and the U.S. from being exposed to the moral, political, and economic pain even of UN debate over sanctions for its failures to make serious efforts to comply with the resolution’s counter-terrorism requirements.

India has its own reasons for being wary of investing authority in the UN, but the larger point is that Indian officials could do much more to develop and execute a strategy to mobilize international political, economic, and moral power against Pakistani security agencies that fail to counter terrorism against India.

Of course, for a strategy of muscular self-restraint to achieve its full power, India (or any other state) must not be acting from a position of weakness. One must have the real option to act forcefully and effectively, and then withhold that option out of a superior self-restraint and moral-strategic wisdom that will be recognized by the opponent and the international community.

Thus India would still need to reform its management of national defense and acquire intelligence, reconnaissance, and strike capabilities that could be used against Pakistan. It would still need to maintain a combination of army, navy and air force capabilities that would prevail in a major conventional war if Pakistan initiated it. India also would need a reliable, survivable nuclear force to deter unbounded escalation. Finally, and all too often neglected in the discourse on deterrence and national security, India must be seen willing to negotiate forthcomingly and fairly to resolve the outstanding territorial issues with Pakistan and address the grievances of Kashmir Muslims.

Conclusion

In his memoir, Robert McNamara wrote, looking back particularly on Vietnam: “we failed to recognize that in international affairs, as in other aspects of life, there may be problems for which there are no immediate solutions….At times, we may have to live with an imperfect, untidy world.” The challenges of Indo-Pak relations that I have described and analyzed this evening are truly untidy….and dangerous. And, while Indians and Pakistanis find it easier than Americans to accept the untidiness of the world, they may benefit from encouragement not to fall into the strategic trap that I think McNamara was identifying: That is, the impulse to find immediate solutions to all problems may lead to over-reaction. Over-reaction is another way of describing a strategy that is mistaken because the ends and the means around which it revolves are both disproportionate to the problem.

The use of military force to counter terrorism is an especially tempting solution because it can be enacted very quickly. But it also can quickly escalate to over-reaction. (The U.S. has data on this). This is another reason why the Indian tradition of strategic non-violence, however imperfect, is less risky and more conducive to long-term success than a militaristic strategy to counter terrorism in a nuclearized environment.

But the strategic importance of proportionality and not over-reacting is an introduction to another lecture, for another evening, with another speaker.

Notes

1. McNamara, “The Military Role of Nuclear Weapons: Perceptions and Misperceptions,” Foreign Affairs, 1983.

2. Then the problem of asymmetry emerged for Russia as the Warsaw Pact dissolved and NATO expanded.

3. Here I treat “spectrum” loosely as a structure.

4. Of course, states cannot control all of the external activities of all of their citizens. Terrorists emanate from many states, including the U.S. The key distinction is whether a state does all it can to prevent its territory from being a base of terrorist operations, and if one or more of its citizens engage in terrorism against another country, the intensity with which the home state investigates and brings perpetrators to justice, in cooperation with the state that has been attacked.

5. If India deployed heavy forces which proved victorious, the Pakistani Army and ISI would not retain the capabilities to disarm internal militants. If India only used minimal force to tactically defeat the Pakistani Army in limited areas, then Pakistan would not be compelled by this to disarm the anti-Indian terrorist groups.

6. Sources to come.

7. Indian strategists recognize this risk and thus conceptualize that Indian forces under Cold Start would be demonstrably unable to dismember Pakistan and instead would only be suited to take limited ground, stopping before Pakistan’s nuclear red line would be crossed. However, there are reasons, including insights drawn from experimental psychology and war games, to expect that Pakistan would perceive India’s intentions, capabilities, and actual operations to be more aggressive than India would perceive or intend them to be.

8. As the Indian defense analyst, Major General (ret.) G.D. Bakshi wrote shortly after the Mumbai attack, “A full scale war in response to a singular act of terrorism may not always qualify as a just or proportionate response.” Response “at the lower levels of the escalation ladder…would [be] far more feasible, just and proportionate [and would transfer] the onus of escalation entirely on to Pakistan….Indian air attacks across the [international border/boundary] in response to mass casualty terrorist actions in the Indian mainland would be fully justified.” G. D. Bakshi, “Mumbai Redux: Debating India’s Strategic Response Options,” Journal of Defence Studies, vol. 3, No. 4, October 2009, p. 21-22.

9. Shyam Saran, “Is India’ Nuclear Deterrent Credible,” speech delivered at the India Habitat Center, New Delhi, April 24, 2013, p. 16.

10. China could provide an alternate model for India: Beijing has not sought nuclear symmetry vis a vis the U.S. and Russia, deploying battlefield nuclear weapons in large numbers. However, the U.S. and Russia do not pose the sorts of threats to China that Pakistan does to India. Since the 1969 Sino-Soviet border war, Russia and the U.S. have not posed threats to mobilize forces to take Chinese territory, or to conduct terrorist operations in China.

11. Hannah Arendt, “Reflections on Violence,” New York Review of Books, February 27, 1969, reprinted in New York Review of Books, July 11, 2013, p. 66.

12. The New Yorker, “The Back Channel,” March 2, 2009.

This speech was priginally published on the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.