Source: Arab Reform Initiative

Since the removal of the Mubarak regime in 2011, the United States has struggled to develop a coherent policy of engagement that can protect American interests while winning trust among Egyptians and their leaders. American assistance, either funding for NGOs during the Morsi period or military assistance to the Sisi regime, has often been unpopular with many Egyptians. Throughout this period, the US has focused on cooperating with whoever is in power in order to continue security cooperation. Cooperation with the regime, however, may clash with American interests in supporting a new democratic opening. With tens of thousands in jail and hundreds condemned to death, the US cannot pretend that Egypt is transitioning toward democracy.

The future of US policy should be shaped according to a forthright assessment of what, rather than whom, the United States should support in Egypt. She recommends several principles that the US should guide such an assessment, including the continued need for stability, the importance of ending political polarization, the need for an improved economy and the importance of engagement with the population in the restive Sinai region.

American policy toward Egypt since the 2011 revolution has been indecisive at times, but it has been driven by one constant imperative: get along with whoever is in power in order to continue security cooperation. While such a policy might appear to be the very soul of practicality, it has instead resulted in all camps—nationalists, Islamists, and liberals—becoming furious at the United States and suspicious of its intentions.

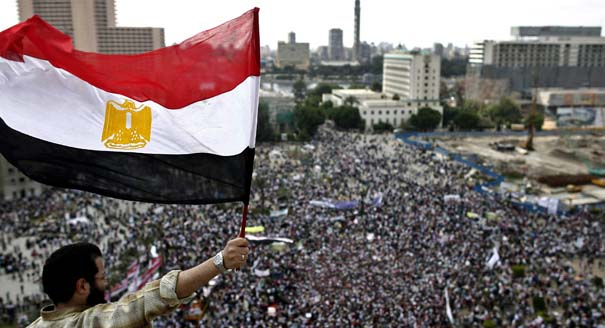

Egypt’s popular uprising of January 2011 put the United States—a nation that prides itself on supporting democracy worldwide, but which had a 40-year relationship with Egypt built on strong ties with the military—in an uncomfortable position. President Barack Obama had placed less emphasis on democracy promotion than his predecessor, but he pivoted neatly within a week of the beginning of the uprising and called for President Hosni Mubarak to step down. There followed a rash of enthusiasm in Washington for the new democratic opening in Egypt, but that sentiment lasted less than a year.The United States had a difficult time marshaling economic assistance for Egypt early in the transition, partly because it occurred amidst the financial crisis in the United States and Europe and partly because it was nearly impossible to coordinate such assistance with the military-led transitional government. In spring 2011, the United States hastily cobbled together a package of $150 million (most of it reprogrammed funds already intended for Egypt) in emergency assistance, which then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced on a trip to Cairo in March. Far from welcoming the assistance, however, Egyptians generally denigrated it as far too little.

Moreover, Minister of International Cooperation Faiza Aboul Naga objected strongly to the fact that roughly $65 million of the assistance would go to American and Egyptian nongovernmental organizations rather than to the government. She initiated a public campaign against the assistance to NGOs, accusing the United States of carrying out illegal acts and trying to manipulate Egyptian politics. Still, President Obama offered to increase assistance in May 2011, proffering $1 billion in debt relief over three years in the form of a debt swap to be spent on mutually-agreed programs such as education. But the terms of the swap could not be negotiated with Aboul Naga’s ministry, which was in charge of negotiating foreign assistance agreements.

By the end of 2011, Aboul Naga’s public campaign against NGOs had become a full-fledged investigation and legal case, and on December 29, 17 Egyptian and American groups were raided and closed down. In June2013, 43 NGO employees (including 19 Americans) were convicted of carrying out activities without permits, although all of the organizations had applied for permits long before.

The NGO case cast a shadow over US-Egyptian relations, but the verdict came as Egypt was electing its first post-uprising president. The American administration was eager to ingratiate itself with the new administration of Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, a group with which American officials had had little contact, so it reacted relatively quietly to the verdict.

Morsi and others from the Brotherhood were eager to build their international bona fides and worked hard at showing they would play a responsible role in foreign affairs, such as by helping the United States to broker a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel in November 2013.American officials also found that Morsi’s advisors were more receptive than the generals of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) had been to reaching a deal with the International Monetary Fund that would involve significant economic reforms. But the honeymoon ended with Morsi’s issuance of a constitutional declaration in late November that paved the way for a constitutional process that would run roughshod over secularists and their constitutional demands.

American officials, fresh from praising Morsi’s constructive role regarding Gaza, were reluctant to criticize the president’s undemocratic moves in public. As opposition to Morsi built, not only among secular opposition and youth groups but also within the police and judiciary, American officials kept largely silent in public. Privately, they worked with European envoys to press Morsi and others from the Brotherhood to compromise with secularists, but Morsi was deaf to such pleas.

Throughout all this turmoil, even after the NGO trial, one aspect of American engagement with Egypt had remained constant: security cooperation, including $1.5 billion in annual assistance to the military. However, the July 3 military coup against Morsi, following massive public demonstrations on June30, tested even this relationship. American laws mandated the suspension of assistance to any military that had overthrown a democratically elected leader in a coup, but American officials sidestepped the legislation by not using the term to describe events in Egypt. At first, they also resisted suspending any aid, trying instead to broker a compromise between Egypt’s political forces. This time, however, it was the military, led by Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, that showed no interest.

As diplomatic attempts at reconciliation collapsed and human rights abuses mounted–notably, the break up of a Cairo sit-in in which some 1000 were killed–the United States began quietly suspending major deliveries of military equipment such as aircraft and tanks. Although American officials stopped short of calling the removal of Morsi a coup, they voiced concern publicly about the undemocratic nature of the move and the human rights abuses that followed–something they had largely refrained from doing during the tenure of either SCAF or Morsi. This provoked a storm of criticism, accusations of support for the Brotherhood, and conspiracy theories from Egyptians supportive of the coup.

At the same time, however, the administration could not quite let the relationship go. Other forms of assistance, such as counterterrorism and economic assistance, continued to go to Egypt, and routine security cooperation (principally military over-flights and warships transiting the Suez Canal) went on. The administration also expressed support for Egypt’s transitional roadmap and appeared eager to restore the military assistance it had suspended. As such, many Brotherhood supporters expressed suspicions that the United States must have given a green light for the coup.

How did the American administration, which tried to ride the wave of change in Egypt in such a way as to preserve bilateral cooperation, end up facing the strongest anti -US sentiment in the country in decades? Some degree of Egyptian public anger might have been unavoidable, as the United States was closely associated with the deposed Mubarak regime. The military-backed government also deliberately fanned anti-US sentiment (planting stories from unnamed official sources about American conspiracies with the Brotherhood to smuggle weapons and terrorists into Egypt) as a way to push back against American pressure and to undercut liberal protest groups seen as connected to the West. The American administration bears part of the blame for alienating all sides, however, due to a policy that was self-serving, inconsistent, and short-sighted.

The United States continued to struggle with policy toward Egypt in 2014 as the country moved toward a presidential election with only one real contender, the very al-Sisi who had removed Morsi. The US Departments of State and Defense tried hard to lift the suspension on military deliveries and succeeded in sending some attack helicopters in spring 2014. But a steady flow of bad news on human rights developments–tens of thousands jailed for protesting, mass trials, hundreds sentenced to death, a draconian anti-protest law, the Brotherhood and 6 April Youth Movement outlawed and its leaders imprisoned–made it difficult to return to business as usual. Several senior members of the US Congress imposed new legislative conditions and hampered administration attempts to restore all military assistance.

As the al-Sisi presidency begins, the United States is badly in need of a new strategy in its relations with Egypt. There is no democratic transition at present and Washington should not pretend there is; at the same time, it will need to preserve some cooperation with the al-Sisi government and find ways to support the strong and ongoing demands of the Egyptian people for bread, freedom, and justice. Such a strategy should be based on a forthright assessment of what, rather than whom, the United States should support in Egypt.

Simple principles can help to guide this assessment. First, only by maintaining a reasonable level of stability can Egypt be a good security ally or counterterrorism partner for the United States, a good peace partner for Israel, and a good trade partner for Europe. Second, overcoming the current situation of repression, protest, and escalating insurgency will require a situation in which Egyptians can move beyond polarization to build consensus on the future of their country. Thus, what the United States should support is the opening of space for free expression, political and social pluralism, and civil society activity. Third, Egypt faces dire economic challenges that can only be resolved by responsible government reforms (gradual replacement of subsidies with cash payments to the poor) and facilitating job creation by the private sector (especially small and medium enterprises). Fourth, since Egypt faces a real challenge by terrorist groups based in the Sinai, the United States should support a policy of economic and political engagement with the population in that region in order to combat support for extremism.

This paper was originally published on the Arab Reform Initiative.