From Ukraine to the South and East China Seas, the international system experiences new turbulence, even as it searches a new balance. Ostensibly, the United States and Russia are in a conflict over Ukraine. In reality, they are in a conflict over the fundamentals of the post-Cold War settlement. Russia, pushing back against expanding Western influence, is labeled revisionist and "resurgent." China is not yet in a conflict with the United States, but the Sino-U.S. relationship, too, is experiencing increasing strains. As its power grows, China advances its interests in the maritime zones east and south of its shores, for which it is termed "assertive." Worried, China's smaller neighbors in Asia, like Russia's in Europe, are flocking to seek U.S. protection, thus re-invigorating Cold War-era alliances and creating new informal ones.

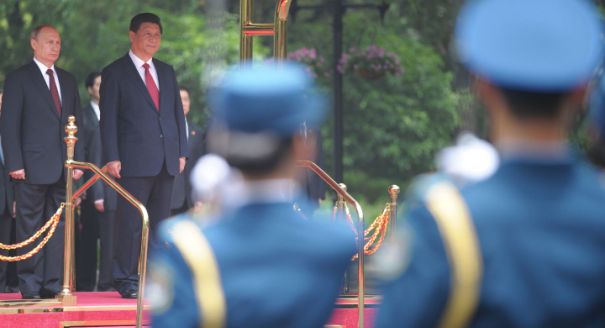

In mid-2014, for the first time in four decades, the United States' relations with China and Russia are substantially worse than those two countries' bilateral relations. The lopsided triangle now being formed and probably ignored in Washington, where Russia is heavily discounted as a factor, has Beijing in a more advantageous position than ever before. This position would allow China access to more resources, and would make its strategic rear in the north even more secure as it deals with the issues south and east of its shores. The result is that the unique position that the United States has held since the 1990s as the dominant power in Eurasia is now history. Symbolically, the Pentagon's quiet departure last month from the Manas air base in Kyrgyzstan closes the book on that era.