Introduction

The passing of Pension Law 319 by Lebanon’s Parliament in December 2023 was a milestone. For decades, the vast majority of the Lebanese people have lived with little or no income security in their old age, a situation that has worsened since the economic-financial crisis that began in 2019. Approximately 80 percent of the Lebanese population has no formal pension coverage, which forces elderly people to rely on family or other types of informal support. Rapid demographic changes—resulting from decreasing fertility rates, longer life expectancies, and high emigration of the working-age population—create serious challenges for the country, which is becoming one of the fastest-aging societies in the region. Even the few fortunate workers in the formal private sector who are enrolled in the country’s social security institution, the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), receive upon retirement a lump-sum amount as an end-of-service indemnity. The amount is inadequate to live a decent life in old age: on average, with forty-five years of employment, the lump sum is equivalent to three years of salaries. In 2023, Lebanon was one of two countries in the Arab region without a pension system for the vast majority of its workers.

Since 2019, Lebanon has experienced the most severe socioeconomic and financial crisis in its history. The economy has contracted for five consecutive years, with GDP falling from $55 billion in 2019 to $22 billion in 2022. The national currency has lost 98 percent of its value; inflation has been in triple digits for four years; and poverty and unemployment rates have increased significantly—with severe implications for social cohesion and stability. Well over 50 percent of the population is estimated to be under the national poverty line, and 74 percent of people aged sixty-five and above are estimated to be income-vulnerable. Social protection systems prior to the crisis were already weak, fragmented, underfunded, regressive, and incapable of meeting the needs of the poor and vulnerable. The crisis further weakened the state’s ability to protect the population, as the collapse of public finances reduced funding for social programs, including health, education, social safety nets, and public pensions.

The new pension law—which entered discussions around twenty years ago—replaces the current end-of-service-indemnity scheme in the NSSF, which was established in 1963 and envisioned as temporary. The specific pension system introduced in Law 319 offers a monthly payment during a retiree’s lifetime through a nonfinancial defined contribution (NDC) pension system. This means that it is a public pension system in which working-age individuals contribute and pay for the benefits of current retirees, as in a classical pay-as-you-go pension system. But the pension is calculated based on the value of the contributions (plus interest) accumulated in individuals’ “notional” accounts—notional because they exist only for accounting purposes and have no real money in them—and life expectancy at retirement. The new law also restructures the NSSF’s governance and operational framework.

If well-designed, the NDC is arguably one of the best systems to balance issues related to work incentives, redistribution, fiscal sustainability, and the management of financial risks. Few countries have been able to introduce this type of reform, so those who made it happen in Lebanon deserve praise. Yet no pension reform is perfect, and there are potential problems with the design of Lebanon’s new pension scheme with respect to the adequacy of benefits and redistributive arrangements, solvency and the distribution of financial risks, impact on the labor market, and transitional arrangements. As policymakers move into the implementation phase of the planned reform, it is important that they consider and tackle these problems, thereby ensuring that Lebanon does not miss a golden opportunity to provide adequate social protection for its population.

Adequacy of Benefits and Redistribution

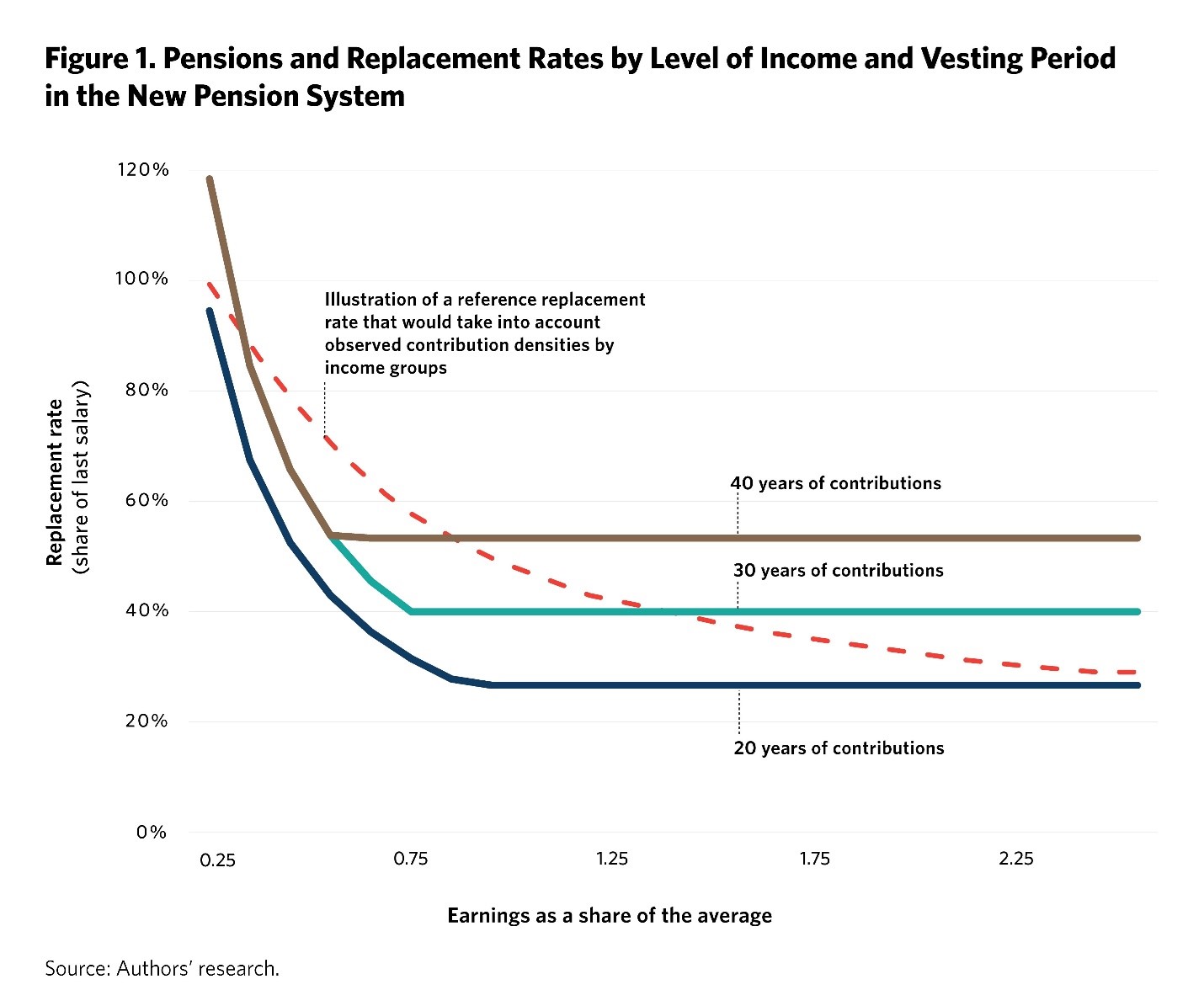

A public pension system can aim to replace 50 percent of preretirement income to the average worker, more to low-income workers, and less to high-income workers. The rationale is that by the time workers retire, many expenditures that are part of active life—mortgages, education and other expenditures for children, and clothing and transportation related to work—will no longer be required. Assuming that health coverage is provided after retirement, a worker with average earnings could maintain standards of living with a pension equal to 70 percent of his or her preretirement income, with 50 percent coming from the public pension system and 20 percent from private savings. Replacement rates would have to be higher for low-income workers because, regardless of their age, there is an incompressible set of expenditures to maintain a decent standard of living. At the other extreme, replacement rates could be lower for high-income workers, as they are expected to have other sources of savings. Hence, the mandate of the public pension system in terms of benefits would imply replacement rates that gradually decline with the level of income (see dotted line in figure 1).

In the new pension system in Lebanon, the pension coming from retirees’ own contributions could range between 20 and 40 percent, depending on the number of years they spent in the system and the growth rate of wages. This pension is calculated by dividing the savings accumulated in the notional individual account (contributions plus interest equal to the growth rate of the average wage of plan members) by a so-called annuity factor that is, more or less, equal to life-expectancy at the age of retirement—for example, 16.4 years for a male aged sixty-four.

But the new system also offers two guarantees in the form of a minimum pension and a minimum replacement rate that together increase replacement rates to the 30–80 percent range, depending on incomes and vesting periods. The first guarantee is a “top-up” to ensure that one’s pension is never below the minimum, which is currently set at 80 percent of the minimum wage if one is a full-career worker. (One receives 55 percent of the minimum wage if one contributes fifteen years and 1.75 percent extra for each additional year, up to 80 percent.) The second guarantee is on the replacement rate; new retirees receive 1.33 percent of the average of their entire career wages for each year of contributions. (Past wages included in the calculation of the average are adjusted by the growth rate of the average wage.)

With these guarantees, a full-career worker would fare well in the new system, but the majority of workers who do not contribute to the pension system for their entire active lives would still receive pensions that might be too low. A full-career worker earning the minimum wage would get a replacement rate of 80 percent, owing to the minimum pension guarantee (the first guarantee), and anybody with an income higher than 75 percent of the average would have a replacement rate of around 53 percent; this is more than the replacement rate it is possible to receive through the contributory pension alone (see orange line in figure 1). But most workers are not full-career; for the average worker, who is more likely to contribute for twenty years, the replacement rate would be 67 percent if earnings are close to the official minimum and only 27 percent if earnings are above 75 percentage of the average (see blue line in figure 1).

The second guarantee (on the replacement rate) is also problematic for another reason: it eliminates the raison d’être of individual contributions/savings. Indeed, most workers, regardless of income, are likely to benefit from the second guarantee. The savings in the notional accounts would become irrelevant because the pension they can finance would be below the pension that is calculated based on the 1.33 percent accrual rate. The NDC system becomes in practice a defined benefit pension system because for most workers the pension would be calculated as a fixed percentage of past earnings and not based on the value of the savings accumulated in their accounts and life expectancy at retirement.

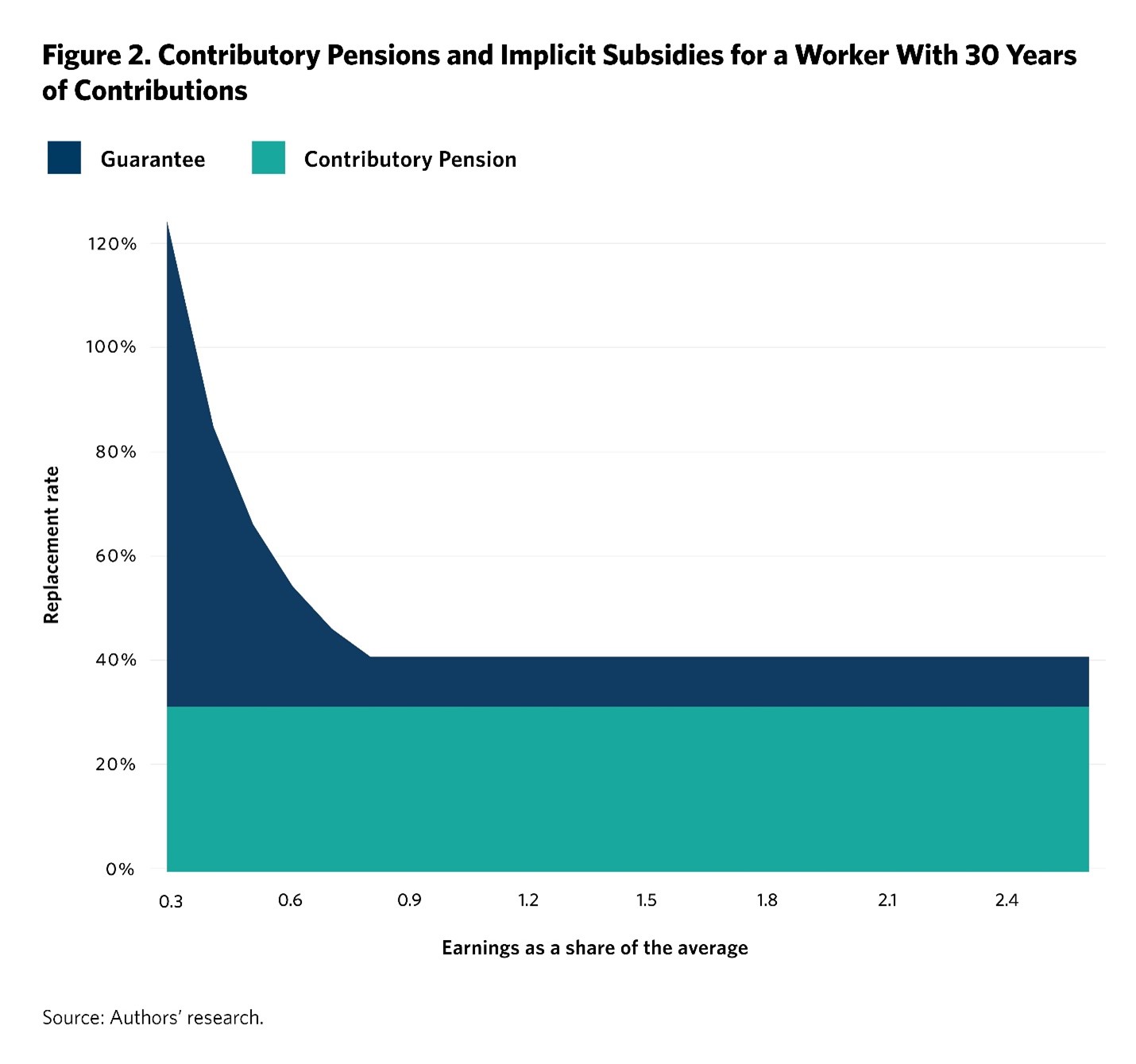

Yet another issue with the second guarantee is that it could prove both unsustainable and regressive. Because the system would be paying more than what individuals would finance with their own contributions, it might not be sustainable; the cost of the guarantee per plan member is not explicit. It might also be regressive because the value of the implicit subsidies (the value of the guarantees above the value of the contributions) would be higher for high-income workers (see figure 2).

There are also problems with the first guarantee. Beyond the fact that it is not good practice to peg the minimum pension to the minimum wage, which is subject to ad-hoc adjustments, “top-ups” are also not a good idea because they reduce incentives to contribute or declare wages in full. If one contributes more and receives a higher contributory pension, the top-up is reduced by the same amount, and one still gets only the minimum pension; there is a 100 percent marginal tax on additional contributions for low-income workers. The extra 1.75 percent of the minimum wage that a worker receives for every extra year of contribution (during which one pays 17 percent of one’s salary) does not compensate for this tax.

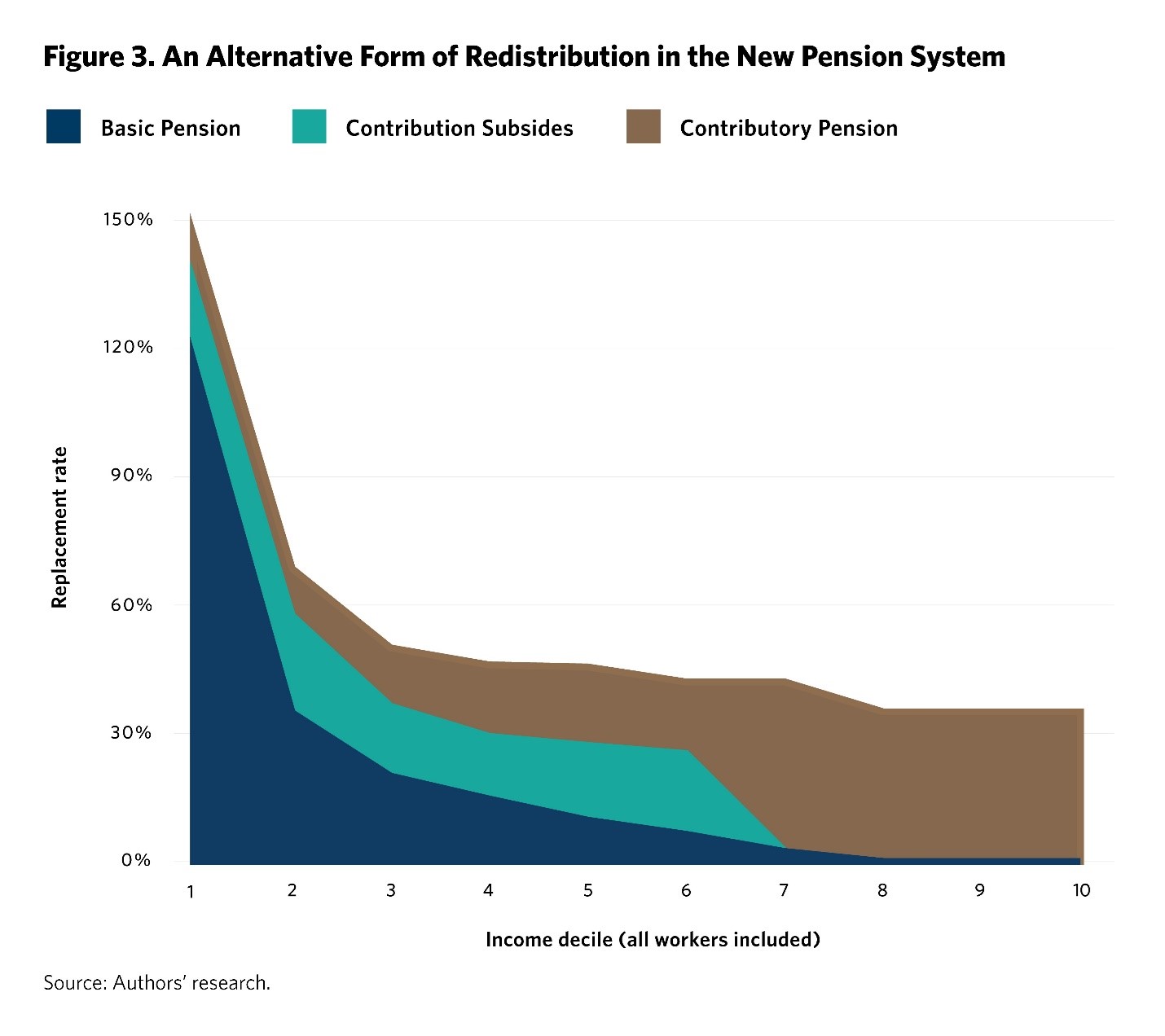

Redistributive arrangements within a pension system are key to ensuring that all workers have an adequate pension during old age, particularly if they spend part of their active lives in the informal sector and have low contribution densities. Yet these arrangements need to be carefully designed to ensure that they are progressive and do not reduce incentives to work and save. A better alternative for Lebanon would have been to introduce a basic tapered pension that is paid regardless of the number of years of contributions, combined with contribution subsidies (matching contributions calculated and paid at the time of retirement) that decline with income. For example, the basic pension could be equivalent to 25 percent of average earnings for workers in the first decile of the income distribution and then decline to zero for individuals in the seventh decile (a 20 percent taper or clawback). Contribution subsidies, on the other hand, could start at 60 percent for low-income workers and fall to nil for individuals in the eighth decile (see figure 3). This type of redistribution would be targeted and transparent (meaning the fiscal cost would be explicit), while creating strong incentives to contribute. And, preferably, it would be financed by general revenues and not implicit taxes on labor, which reduce incentives for the creation of formal jobs.

Solvency and Distribution of Financial Risks

As with any other financial institution, the solvency of a pension system requires that, at all times, liabilities be equal to assets. The main liabilities include both pensions-in-payment, which the fund will continue to credit until all retirees die, and accrued pension rights of active members, which depend on past contributions. The structure of assets, on the other hand, depends on the type of system. In fully funded systems, the assets include financial assets such as deposits, equity, or bonds, as well as real assets such as buildings. In the new NDC system in Lebanon, there is a third asset—less well-known—called the pay-as-you-go asset. Technicalities aside, this asset is like investing in a type of government bond that pays a share of future contributions. The new law does not make reference to this asset, yet it is a critical determinant of the solvency of the new system.

Indeed, the interest rate that the new system can pay on the contributions that accumulate in notional individual accounts should be related to the growth rates of the financial and pay-as-you-go assets of the NSSF. Instead, the interest rate set by the new law is equal to the growth rate of the covered average wage. This could be a good approximation of the sustainable rate of return on contributions, but it still requires having a mechanism to restore solvency when liabilities outpace assets. At this stage, the value of these NSSF assets and liabilities is unclear because the actuarial reports and other analytical documents that informed the law have not been made public. It is also unclear what the costs are of the guarantees on the minimum pension and the minimum replacement rate. This lack of transparency creates concerns about the credibility of the reform and may increase Lebanese citizens’ distrust of the NSSF.

There is one more important question that is often overlooked in pension reform: how to allocate financial risks among the government, employers, workers, and retirees. What happens when, due to a crisis such as the coronavirus pandemic or a financial meltdown, the assets of the pension system contract abruptly and severely, falling below liabilities? In a fully funded defined-contribution system, the answer is clear: workers bear the risk. If the value of the assets of the pension fund falls, it means the savings workers have in their individual accounts also fall by the same amount, thereby maintaining solvency.

But this is an unfortunate outcome for workers, particularly those close to retirement. The virtue of NDC systems is that there is more leeway to allocate risks. For instance, the new system could fix the rate of return on contributions for a given period of time (so that it would not fluctuate with the growth rate of the average wage), and the government would assume any temporary, unfunded liability that emerges. At any rate, it is important to have a clear mechanism to allocate financial risks—something that is currently not part of the new law.

Coverage, Labor Markets, and Transitioning to a New System

Pension systems and other social insurance programs were originally conceived with the idea that, as economies develop, most workers would eventually end up as wage employees in medium or large formal firms. This has not happened and is unlikely to happen anytime soon, particularly in middle- and low-income countries. Not only do many wage employees work for small, low-productivity, and informal firms, but also, between 20 and 40 percent of workers are self-employed. Some of these are in liberal professions, and others are employers, but the majority are farmers or self-employed workers managing household enterprises.

A well-designed pension system should be integrated into local labor markets and be able to cover all workers, regardless of the type of job or economic sector—including the informal sector, which in Lebanon employs the majority of the labor force. There are a few conditions for a pension system to work this way: there should be a clear link between contributions and benefits so that new entrants do not compromise the solvency of the system; there should be transparent and progressive redistributive arrangements to help those who cannot contribute or save enough; these redistributive arrangements should provide incentives to enroll and contribute, unlike pension top-ups; and redistribution should not be financed by implicit taxes on labor, which can reduce the share of formal work. None of these conditions are present in Lebanon’s new system. In addition, the new law is silent regarding the pension system for the public sector (both civil servants and members of the armed forces), which itself needs to be reformed. Ideally, the new law would have included provisions for a national pension system that merges the public and private systems and treats all workers alike.

Working out the right transition arrangements is a very important part of a reform package that introduces structural changes to the pension system. The key is to ensure that the new system starts with a clean balance sheet, whereby assets are equal to liabilities. This implies calculating any unfunded liabilities in place prior to the reform and ensuring that they are financed through dedicated government bonds. In the case of Lebanon—particularly given the current economic crisis and the significant wage adjustments that are taking place—priority should have been assigned to shielding employers, in particular small enterprises, from the unfunded liabilities of the end-of-service indemnity (the fact that the last employer is responsible for financing any gap between the lump sum benefit and accumulated contributions plus interests). These liabilities are likely to increase, given that the lump sum will be calculated at much higher wages than those over which contributions were paid. Unfortunately, instead of eliminating the end-of-service indemnity under the transition arrangements set by Law 319, workers close to retirement are given the choice between the old-lump sum and the new pension, and those with salaries more than double the minimum wage are likely to choose the former.

Conclusion

The stakeholders involved in reforming Lebanon’s pension system recognize some of the issues raised in this article. But they also stress that Pension Law 319 is about finding political compromises. And they point to one of the main achievements of the reform: the change in the governance structure of the NSSF that includes having fewer board members, fewer meetings, and the separation between a newly established investment committee and the position of NSSF director general. These are important changes, and they have the potential to improve the administration of the new system, but they are not enough to address the problems of adequacy of benefits, solvency, and coverage.

Since the new pension system has been approved by Parliament, it is unclear at this stage what can be done to improve the design of redistributive arrangements, in particular the design of the second guarantee. But it is a priority to calculate the assets and liabilities of the NSSF and the fiscal costs of the proposed reforms. Additionally, it should be possible to create mechanisms that ensure the solvency of the new system, along with others that allocate financial risks. Finally, it is important to revisit the transition arrangements and better shield the private sector from the unfunded liabilities of the end-of-service indemnity. With Lebanon yet to fix its banking system or stabilize the economy five years into the crisis, the last thing the country needs is to add to its financial woes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For more details regarding the license deed, please visit: CC BY 4.0 Deed | Attribution 4.0 International | Creative Commons.