Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

{

"authors": [

"Tang Xiaoyang"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"China and the Developing World",

"China’s Foreign Relations"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Southern, Eastern, and Western Africa",

"East Asia",

"China"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

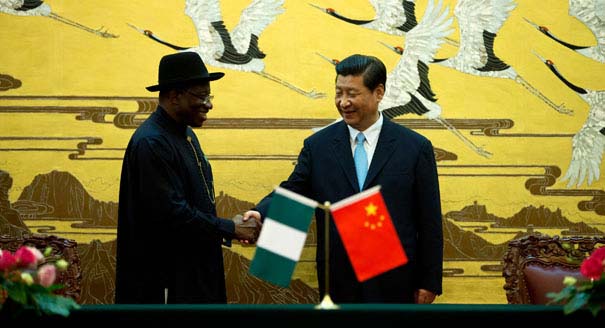

Source: Getty

China is facilitating economic development in African countries not only through government-directed investment but also through the market forces unleashed by Chinese value chains.

Source: Phoenix Weekly

With the relationship between China and Africa as close as it has been recently, the international community has long raised the question of whether China’s involvement amounts to “neocolonialism” or “the purchasing of friends.” It is true that economic diplomacy does currently dominate the relationship between China and Africa. However, such diplomacy does not only focus on economic exchanges—these instances of mutually beneficial economic interactions also open doors to wide-ranging, ongoing exchanges that are political, social, and cultural in nature. Economic diplomacy does not merely involve government decisions—rather, government policy only serves the function of providing direction, offering limited support, and reducing barriers.

Economic diplomacy also includes wide-ranging interactions between China and Africa at the societal level. As economic incentives serve as a fundamental driving force for globalization and modernization, economic diplomacy between China and Africa is also an important contributor to both parties’ efforts to advance along the path to modernization. Economic diplomacy between China and Africa is also an important part of developing the globalized market economy.

Since China’s period of reform and opening up, the market economy has unleashed China’s energy along industrial value chains and allowed these networks to reach new heights of economic development. In terms of foreign policy, China’s approach to Africa has already moved from providing political support and the dominance of ideological considerations to a sort of economic diplomacy that is focused on facilitating win-win cooperation through the market economy.Once thought of as a “hopeless continent,” Africa has undergone structural economic adjustments and encouraged privatization over the past decade, as opposed to the past practices of relying largely on policy adjustments and external aid. Compared with Western countries, one sees that China’s economic diplomacy policies toward Africa are relatively more unique and appropriate. This is because Chinese and African industrial chains and economies have proven to be highly complementary.

As one of the world’s important centers for industrial production, China’s economic development is currently in the midst of transition and needs Africa’s energy and resources. At the same time, China can provide Africa with low-cost industrial products as well as civil engineering teams. The interconnection of these industrial chains will only be able to continue developing in a politically stable environment. The United States and European countries cannot accomplish this, because their levels of industrial development are comparatively high. African markets do not strongly favor cutting-edge technological products, while Western countries are not especially interested in making investments in the small, risky African market.

Therefore, China and Africa’s closely integrated economic development is not merely a result of the policies by either party. This development is more a result of the links and interactions that global industrial chains have made possible.

Compared with the methods that Western countries have used to developing resources in or promoting aid to African states, China seems to have taken an opposite, more diversified approach to growth in Africa. Just as a Japanese scholar put it, China is steadily constructing a unique and stable path for providing aid.

Economically speaking, there are three major models that guide how aid is given, including a pure-aid model, a pure-investment model, and one model that combines commerce and aid.

The pure-aid model is primarily a continuation of the assistance that China had previously extended toward Africa. Between 1950 and 1970, China initiated a large number of purely aid-based projects in Africa. Examples of these projects include the Tanzania Zambia Railway as well as some large-scale farms. In agriculture, investments tend to be large, risks tend to be high, and profitable returns require a long timeframe, so it is difficult for such investment to introduce market mechanisms. In light of this, China will continue to provide the aid that it has in the past for a number of African agricultural projects. Overall, this type of project will account for a very small portion of total projects.

The pure-investment type is primarily focused on manufacturing and extracting energy resources. With regard to the latter, China’s need for resources is structurally changing. State-owned enterprises such as PetroChina, Sinopec, and CNOOC are extracting oil in countries in West Africa such as Nigeria and also in countries in East Africa such as Sudan. Angola is already China’s second biggest source of petroleum, and the petroleum that China has extracted in Sudan accounts for 5 percent of the country’s total oil exports. Corporations such as the China Nonferrous Metals Group are also extracting minerals in countries such as Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It should be pointed out that while China is importing resources from Africa that does not mean that China has taken possession of (or occupied) these resources. Chinese enterprises are involved in the extraction of Africa’s natural resources primarily as participating shareholders, and it is actually the United States and European countries that have taken the majority share and operation rights of the oil fields and mineral resources. Even India has done this more frequently than China.

When it comes to manufacturing, small privately run Chinese enterprises have been increasing their investments in Africa. This includes the shoe industry and the manufacturing of small commodities. Comparatively, the manufacturing industry needs to become more competitive in the worldwide market, for example when it comes to the cost of labor and meeting the needs of the market. Since the African market environment is still in need of improvement, China’s pure-investment type projects have had quite a few difficulties. At the same time, however, these projects are gradually maturing in spite of these troubles.

It is the combination of commerce and aid that has greater Chinese characteristics. This is especially true when it comes to infrastructure construction, for example railroad construction projects in Angola and Kenya or a light rail construction projects in Ethiopia. Infrastructure projects have the dual properties of serving as both commercial products as well as public goods. When China is carrying out infrastructure construction projects in Africa, it will often use preferential credit provided by the Export-Import Bank of China or the China Development Bank. An important example of this is what scholars have been calling the “Angola Model,” in which China helps Angola with commercial loans for infrastructural construction, which are guaranteed with oil. Past experience has proven that this type of model is highly sustainable.

The latter two developmental models have resulted from an important shift that China has made over the last decade. These approaches have had greater and more positive effects for Africa’s development in terms of the globalized economy’s industrial chains. Careful analysis shows that aid provision alone will not necessarily produce the best results, because such a model would likely lead to African countries becoming dependent, while at the same time weakening progress in these countries’ industrialization and modernization.

The African continent has an area of 30 million square kilometers and includes more than 50 countries. Chinese citizens in Africa chiefly live in the southern part of the continent, especially in South Africa. In the 1990s, Chinese business people (including many hailing from Fujian) went to South Africa, the continent’s most developed region, in search of opportunities for development. For the past two decades, Chinese people have established an extensive presence in the country’s mining, machine-production, electronics, science and technology, and small commodity industries. They have also established a large number of China-town residential districts.

Another place where Chinese people arrived relatively early and established a broad presence is Nigeria in western Africa. With its population of 200 million, the country offers an extensive market. Early in the 1970s, the four great families of Hong Kong began searching for commercial opportunities there. From the 1980s onward, increasing numbers of mainland Chinese business people, contracting companies, and oil companies have come to Nigeria. Now, the country’s steel factories, plastic factories, ceramics factories, furniture factories, construction companies, and oil companies all exhibit the influence of Chinese business people.

Countries such as Angola, Sudan, Zambia, and Ethiopia have also attracted great numbers of people from China. At the outset, Chinese people went to these countries for natural resources, but as time progressed, their presence began to expand into infrastructural construction, agricultural demonstration centers, small commodities markets, and other industries. This represents one of the most important changes in China’s economic diplomacy toward Africa in the past decade, namely that Chinese business people have broadened their involvement from solely energy-related natural resources to a number of different sectors involving production along various value chains.

In addition, the African continent has its own complex history of colonialism. Chinese populations have expanded from African countries in southern and eastern Africa once under Great Britain’s influence to countries in western Africa that used to fall under French influence. Chinese enterprises and business people that are active on the front lines in Africa urgently need individuals that have mastered the French language.

As economic diplomacy between China and Africa becomes more diversified and the number of Chinese people in Africa continues to increase, the next issue that needs to be addressed is overseas regulation. A small portion of Chinese enterprises have already become more conscious of the importance of learning about local laws and regulations, learning about legal hiring practices, studying local languages and cultures, and thereby slowly becoming integrated into local communities. But even so, a large number of Chinese enterprises in Africa are still like “untended sheep”, loosely dispersed and not overseen closely by a central authority. In a large number of African countries and regions that have yet to establish mature systems for regulating markets, the issue of how Chinese enterprises operating in local markets should be regulated remains a topic in need of further discussion and exploration.

Many different aspects of China’s economic diplomacy toward Africa are gradually developing, including its contours, the personnel involved, aid programs, and also investment amounts. In the eyes of a number of foreign scholars, this diplomacy has brought China not only economic gains, but also great political and diplomatic benefits. For example, China has been able to host great international events, including the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. This would not have been possible without strong support from China’s African brothers and sisters on the international stage.

However, as an economic latecomer, China’s overall influence in Africa is significantly less compared with that enjoyed by developed countries like United States, Japan, and others in Europe. In addition to the influence stemming from many years of colonialism and the influence of mass media, differences in how aid is provided is another important reason for this difference.

When USAID designs an aid program or plan, policy issues are an important factor. They are typically based on strategies that African countries or regional organizations have adopted. These aid programs also conduct detailed research on the goals proposed in these plans, make targeted suggestions for aid programs to local governments, provide technical advice, and assist in implementing these strategies. European countries, the United States, and Japan have emphasized that aid needs to be embedded in African countries’ development plans. These policies are evaluated meticulously.

Currently, China’s strategic planning and research toward African countries is still insufficient. China’s aid programs, such as training seminars, hospitals, schools, demonstration centers, and cooperation zones, are generally first designed and planned out by the relevant departments and committees in China, and then African countries are asked if they need such programs. In such cases, African countries will often feel that they are receiving something for free and will gladly accept. However, many of these aid programs are divorced from these countries’ internal governmental systems, and it is very difficult to include these programs in their national planning. Therefore, on the one hand, African countries feel that they can get along with or without such programs. On the other hand, China’s influence on the policies of African countries is limited. For example, after the agricultural demonstration center in Tanzania was established, there was a shortage of individuals ready to take part in training. This was because the local government did not have the enthusiasm or the energy to mobilize individuals to participate.

This article was originally published in Chinese by Phoenix Weekly.

Tang Xiaoyang

Former Resident Scholar and Deputy Director, Carnegie-Tsinghua Center; Chair and Professor, Department of International Relations, Tsinghua University

Tang Xiaoyang is the chair and a professor in the Department of International Relations at Tsinghua University. He was a resident scholar and the deputy director at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center until June 2020.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

Cargo time release studies offer a path to greater economic gains and higher trust between neighboring countries.

Nikita Singla

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont