Source: Journal of Democracy

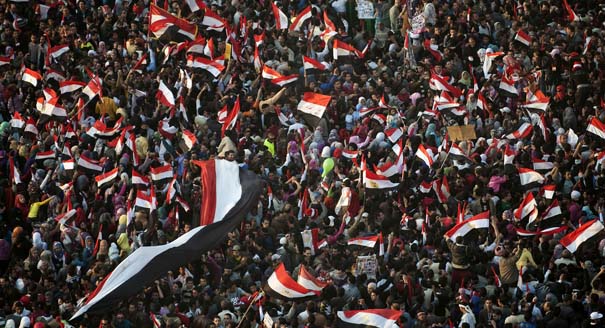

The handful of political openings that occurred in Arab countries after the 2011 uprisings have yielded a bitter harvest that Arabs and non-Arabs alike are struggling to comprehend. Tunisia is a nascent democracy, but it is fragile and torn by savage terror attacks. Libya and Yemen have broken down amid militia strife that has become a stage for proxy warfare. Syria is being consumed by the flames of a terrifying, multisided civil war that has seen the use of chemical weapons and the rise of a terrorist state in eastern Syria and western Iraq. And Egypt has undergone a vicious resurgence of authoritarianism. Observers will probably still be arguing about what went wrong when the next wave of change hits the region.

Nonetheless, it is now nearly five years since a young Tunisian fruit vendor’s December 2010 self-immolation lit a fuse that rocked the Arab world, and one can begin to discern what happened and what did not. Some on-the-fly diagnoses of the Arab countries’ failure to build more inclusive political institutions and processes will likely stand the test of time. In Egypt and Yemen, too many strongmen from the old regime remained in place or at least in a position to undermine the new order, with the help of other regional powers eager to prevent that new order from succeeding.Yet the essays that follow go a long way toward demolishing certain other early analyses of what went awry following the “Arab Spring.” Arab publics never really wanted democracy in the first place, one argument goes; they wanted economic betterment and gave up on the idea of democratic governance as soon as insecurity loomed and material benefits failed to appear. Another argument is that the Arab uprisings were all just so much hype, a soap bubble of social- and broadcast-media enthusiasm that quickly collapsed.

Public-opinion trends in countries that experienced popular uprisings in 2011 have been hard to track and subject to widely divergent claims. Did citizens of such countries initially want democracy, only to sour on the idea after watching their neighbors’ countries—or their own—succumb to instability and strife? Some of the competing claims about this have been based on assessments of confusing events such as the 2013 mass demonstrations against Egypt’s first freely elected president, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi.1 Other claims rest on polls of limited usefulness that asked questions in a particular way—for example whether democracy should be instituted “in the next year” (of course that made people in post-Qadhafi Libya nervous, and they tended to say no).2 And Arab media have sometimes provided a distorted lens through which to view public opinion, due to deliberate manipulation or strong pressures on reporters or owners of media.

The lack of reliable opinion polling is a major obstacle to understanding which views prevail in Arab countries. The Arab Barometer, which has been surveying people in the Arab world since 2006, helps to fill the gap. The contribution in this issue by Michael Robbins, the Arab Barometer’s director, compares the answers that respondents gave to questions about democracy in both the Barometer’s second and third waves (surveys carried out in 2010–11 and 2012–14, respectively). The survey takers covered nine Arab countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen.

The findings that Robbins distills from this opinion research are surprising. Public support for democracy (as indicated by those willing to say that it is a “good” or “very good” system of governance) held steady through both waves at a robust 70 percent or more across most countries. This is particularly striking since the second wave reached completion only after civil war had erupted in Libya and Syria, a military coup had toppled Morsi in Egypt, and Tunisia had come under terrorist assault. Storms abounded, in other words, but Arab publics would not give up the ship and remained on board with democracy. Arab citizens were only too well aware of the economic dislocations and security problems that came on the heels of the uprisings, but refused to blame democracy for them.

After much coverage of the role of social and broadcast media in sparking or fueling the 2011 uprisings,3 Marc Lynch’s article is a sober evaluation of the media’s role in what came after. Many observers believe that the media was not actually as influential as it was first thought to be, and that street-level, people-to-people interactions mattered most. Lynch goes further, however, and argues that the media contributed to the uprisings’ failure. Arab mass media may have brought people together at times—as when millions watched the same demonstrations on satellite television, for example—but all too soon Arab media outlets fell under the control of polarizing forces. Islamists and non-Islamists followed entirely different media, and even transnational media such as Al Jazeera were pigeonholed and ended up contributing indirectly to the “trashing of the transitions.” Lynch includes a note of hope, however, for he thinks that Arab media may turn again when challenges arise to the current authoritarian backlash.

The role played by various political players—especially Islamist and secular political parties—has been one of the most hotly argued topics among those who ponder why most of the Arab uprisings failed to give rise to viable democratic transitions. One oft-heard narrative holds that Islamist parties always sweep elections when given the chance, and will do anything to keep the power thus gained. Confronted with the contrary example of Tunisia, many have attributed the course followed by Ennahda— which agreed to omit mention of Islamic law from the new constitution and ceded power before its electoral mandate was finished—to that Islamist party’s preexisting ideological moderation relative to its counterparts in other Arab countries. If only the Arab world’s small, ill-prepared secular parties had been better positioned to compete with Islamists, another argument goes, surely the transitions would have been smoother and the likelihood of liberal principles being enshrined in new constitutions and laws correspondingly greater.

Correcting Misperceptions

The final three essays in this cluster are highly relevant to these concerns. Each goes a long way toward correcting prevailing misperceptions. Charles Kurzman and Didem Türko¢glu address two of the most persistent beliefs about democracy in the Arab world—namely, that Islamists always win free elections, and that once Islamists do so they ditch compromises and go back to longstanding positions such as an emphasis on Islamic law as the source and standard of legislation.

It is true, Kurzman and Türko¢glu say, that Islamists often win big in the first elections that follow a political opening. But then, the authors hasten to add, the picture changes: Voters tend to sour on the performance while in office of Islamists, who can go from “win big” to “lose big” at the drop of a ballot paper. In examining elections in fifteen Muslim-majority (though not exclusively Arab) countries since 1970, Kurzman and Türko¢glu find that Islamists (a catchall designation meaning all candidates from all Islamist parties taken together) win on average 15 percent of parliamentary seats. Since 2011, moreover, this average has hardly budged. Regarding the position of Islamist parties on some key issues such as the status of shari‘a and the rights of women, the authors detect general movement in a liberal direction up until about 2000, and relatively little change thereafter (including the years since 2011). Support for democratic processes, on the other hand, has continued to rise among Islamists since 2000.

As for Ennahda’s vaunted moderation, Kasper Ly Netterstrøm shows that this Islamist party agreed to keep shari‘a out of the Tunisian constitution while putting freedom of conscience in because it had to do so in order to keep a share of power, and not because it was informed by some preexisting spirit of moderation. To put it bluntly, Ennahda’s leaders acted out of fear. They were afraid that letting their country’s democratic transition fail might bring back a repressive regime that would target them once again. The religious and ideological justifications that Ennahda’s leaders offered for their compromise, says Netterstrøm, came only after the fact. But then, interestingly, he goes on to speculate that these justifications may change the way in which many Ennahda members think about what it means to be an Islamist and a Muslim.

Alongside the idea that Ennahda is a rare exemplar of Islamist moderation is the widespread notion that the Middle East’s secular political parties would surely be better stewards of liberalism if only they were able to win elections. The rap against these parties has always been that they are elitist and weak at the grassroots, hence easily thrashed at the polls by Islamists who know how to build support outside the tonier neighborhoods of a few big cities. But Mieczys³aw Boduszyñski, Kristin Fabbe, and Christopher Lamont make us wonder if these secular parties are really ready for democratic prime time.

The authors’ research regarding Egypt, Tunisia, and Turkey shows that in each country most of the larger secular parties have roots in authoritarian regimes and close ties to the security state. They also tend to be internally undemocratic and thus prone to factional splits (dissidents who lack “voice” still have “exit,” to use Albert O. Hirschman’s terms). Observers, say Boduszyñski and his colleagues, dwell on Islamists’ failings too much and on secular parties’ flaws too little. You need to look at both if you want to understand why attempts at democratic transition in these countries have been so troubled. Moreover, if you seek reliable support for liberal tendencies in the Middle East, the authors add, you are better advised to look to civil society rather than political parties, at least for now.

Grasping the reasons behind political upheavals as they are happening or after they have just occurred is always hard. In today’s Middle East, there is a hot, three-sided power struggle going on among elites long accustomed to rule, other political forces that have long existed but had little chance at power, and newer forces born of a rising generation with different ideas about how citizens and governments should relate. Each of these groups has, at various times, pushed its narrative forcefully both in the region and in the West, with echoes that are heard in media coverage and even in scholarly writings.

But the essays gathered in this issue of the Journal of Democracy do help to clarify a few points. There is still much support for the idea of democratic government among Arab citizens, but also a great deal of weakness among other actors—such as political parties and media outlets— that will need to play more constructive roles if the difficult task of building democracy is ever to be accomplished. These factors must be kept in mind by those who wish to make the next big wave of change in the Arab world one that will favor democracy—an outcome that is anything but certain.

1 Hernando de Soto, “What the Arab World Really Wants,” Spectator, 13 July 2013, www.spectator.co.uk/features/8959621/what-the-arab-world-really-wants.

2 “Libyans Not Keen on Democracy, Suggests Survey,” BBC, 15 February 2012, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-17045265.

3 See, among others, John Pollock, “Streetbook: How Egyptian and Tunisian Youth Hacked the Arab Spring,” MIT Technology Review, 23 August 2011, www.technologyreview.com/featuredstory/425137/streetbook; Robert F. Worth and David D. Kirkpatrick, “Seizing a Moment, Al Jazeera Galvanizes Arab Frustration,” New York Times, 27 January 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/01/28/world/middleeast/28jazeera.html.

This article originally appeared at the Journal of Democracy.