Tatiana Stanovaya

{

"authors": [

"Tatiana Stanovaya"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

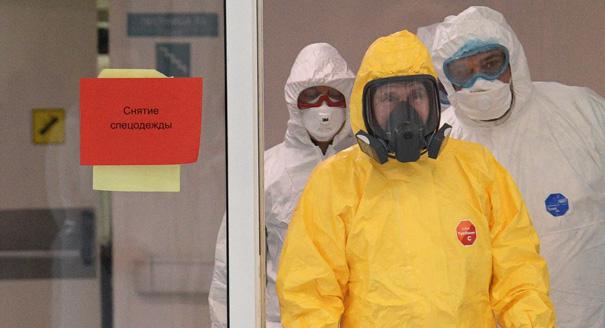

Source: Getty

No Longer the People's President: the New Putin

Vladimir Putin has stopped being the charismatic champion of the people and become the champion of the elite. He has changed into Putin the Strategist, focused on geopolitics. Losing interest in the detail of domestic policy, he has become part of the oligarchic system he created.

The old Putin is gone.

The Russian president used to be a charismatic leader of the authoritarian type, while remaining "one of us" for ordinary Russians—someone who related to their wants and needs. This was the man who personally challenged terrorists, built the famous power vertical, and banished the oligarchs.

Putin's annual presidential press conference at the Kremlin on December 17 offered the Russian public someone different: a new leader who is the product of geopolitical crisis, economic failure, and personal psychological changes.

The change in the nature of Putin’s political leadership—his estrangement from the public and stronger identification with the elite—has been obvious since the spring. This week we saw it on view more completely.

The new Putin no longer delves into financial and economic questions, amazing the audience with his in-depth statistical recitations. His can’t properly engage in a conversation on budgetary or financial issues.

Putin's introduction and prepared statement addressing the economic situation, on which he dwelled quite extensively at the beginning of the press conference, were actually prepared before the steep fall in oil prices over the last week.

“We are past the peak of the crisis,” said Putin. But that comment was prepared for a situation when oil prices were a third higher than they are now. Admitting that “we will not rush to adjust the budget for now,” Putin said in effect that he doesn’t know if it has to be adjusted or under what circumstances that would happen. He has no answer to the question.

That was just one instance of "I don't know." It appears the president doesn’t know if Rosneft should be privatized. “No one knows,” he says. He doesn’t know if the retirement age will be increased, and, if yes, how and when. He doesn’t "really understand what happened” with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the Islamic State.

Apparently, Putin just doesn’t want to know or understand anything that he finds boring. That’s for other parts of the government.

The only thing that interests Putin nowadays is the military operation in Syria and related issues. Even the issue of Ukraine, which would have provoked a lengthy emotional reaction in the past, got lost in a discussion about custom tariffs. The Donbas theme has lost its piquancy for Putin, and he no longer bothers to equivocate about a Russian military presence there.

A narrowing of expertise means delegating responsibility, primarily to the government. But, by kicking issues downstairs, the president is more dependent on the system he created. That is why Putin said, for the first time ever, that there were no plans to reshuffle the government. The president is no longer the enforcer. Instead, his government is full of little Putins.

A stark illustration of this trend was Putin’s answer to the question about raising the retirement age. It’s a strategically important socioeconomic issue on which Putin has always defended the people against the liberals in government, who want Russians to work longer.

But, on December 17, he uttered a phrase that would have been impossible a few years ago, saying, “I’ve always resisted raising the retirement age.” In other words, the president is supposedly up against a strong and persuasive force—the government—that is forcing him to give in.

This is not to say the government or Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev is getting stronger. The problem is that, as Putin tries to delegate decisions downwards, the system stops working. No one is prepared to take responsibility. For the past three years, the government has not made a single meaningful decision in socio-economic policy. They have just carried out Putin's instructions.

The Putin of late 2015 fails to convince. We know he is a politician who can deliver long, eloquent, and convincing speeches. He can hold an audience. He is able to articulate a clear position on both foreign policy—his strongest side—and domestic issues. Yet, none of that was on display at the press conference.

Instead, we saw a Russian leader who has stopped being the people’s president and is now serving the state-affiliated oligarchy. The detailed attention he used to pay to the rights of the small man, and to social issues, has completely disappeared. Instead, Putin defended all the controversial measures that are irking the public: paid parking, the “Platon” toll system for truckers, and removing pension rights for working older citizens.

In one illuminating exchange, Putin was challenged about the behavior of the children of the elite. When he called the accusations “problems of secondary importance,” he inadvertently conceded the truth behind them. He was effectively saying that these “secondary” things are indeed unpleasant, but acceptable. Putin evidently sees discussion of the state oligarchy he constructed, in which officialdom and business are closely intertwined, as an issue for the elite, not the public—as a political matter and not one for criminal investigation.

To put it another way, Putin has stopped being a champion of the people and become a champion of the elite.

In parallel, his language of communication with the people has also changed. This week we didn’t hear any street slang or sexist jokes. The jokes that the president did tell were told against the people. Putin can no longer afford to criticize the oligarchs or the bureaucracy because he has become part of their system.

The new Putin is a politically neutral state strategist—a functionary with faded charisma who feels uneasy in public and has lost interest in government and domestic policy. Instead, we see Putin the Strategist—an international actor who is mainly sending messages to the leaders of other countries and foreign elites.

At home, the reins of government have been handed over to a “collective Putin,” whose job is to suppress the “fifth column” of political opposition, raise the retirement age, and stitch together acceptable budgets.

It is not just diminishing resources and the end of oil-fueled prosperity that has brought about this change (although that has definitely played a role).

Rather, Putin’s psyche has morphed. He now feels that his domestic mission is complete. It’s not that he’s accomplished particular goals, but he believes he built a system that can help accomplish them over time. Now Putin sees Russia's future through the prism of geopolitics.

But this approach leaves the public out of the equation. The question is whether the people are ready to accept this new arrangement—this surrogate Putin—when the real Putin has decided to devote his time to fighting a war in Syria. After all, the people need feeding, just as much as the elite does.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Tatiana Stanovaya is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Signs of an Imminent End to the Ukraine War Are DeceptiveCommentary

- Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Finally in Sight?Commentary

Tatiana Stanovaya

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya