Andrei Kolesnikov

{

"authors": [

"Andrei Kolesnikov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

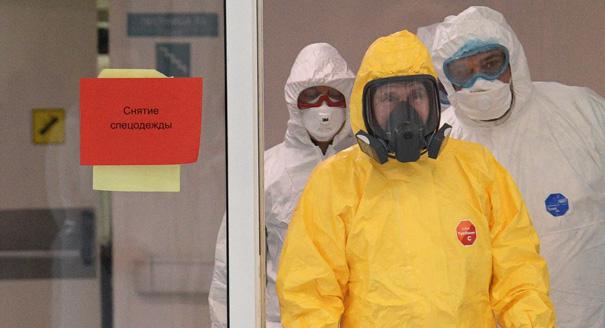

Source: Getty

Russia’s Waiting Room

The Russian system is in a crisis whose outcome is uncertain. But social protest is unlikely to deliver change. Change is more likely to come about through modernization from above.

In Russia, making predictions about even the near future is difficult. The trail ahead is full of false signals and we can all too easily extrapolate yesterday’s trends into tomorrow.

As it enters 2016, Russia is reminiscent of a large waiting room at a huge railway station. The arrival-departure board is blank. No trains are coming in. The final destination is not clear. Even the price of a ticket is unknown. What is more, no one is in a rush to go anywhere: those at the bottom hope for better times, those at the top are watching the oil prices, counting their cash, and looking around for someone else to milk for revenues.

The current Russian system is not designed to function in a situation when the oil price drops below $80 a barrel and, as a result, its social underpinnings are starting to crumble.

Yet we analysts often fail to read the evidence correctly. Take, for example, the recent protests by long-distance truckers against new road taxes, which many believed might even lead to a change in Russia’s political order. Instead, as the truckers appealed to the president to help resolve their problems, they ended up legitimizing a system that lacks political institutions, where only the man at the top can resolve problems.

Economic decline across the country does not portend mass political protests. It doesn’t even promise mass social protests. There may be some local social discontent that will not translate into anything political. The country lacks tools and channels to make that happen.

People will ask their leader to give them some cash, restore justice, or abolish stupid decisions. It’s not that people are afraid to go to jail. They simply fail to see the connection between domestic and foreign policies on the one hand and the string of economic challenges they face—from the weak ruble to high inflation—on the other hand.

The current regime is trying to divine the future from the fluctuation in oil prices. It is drawing new road maps and attempting—in vain—to change small things without changing the overall political framework.

Instead, the authorities should look at the big picture. By 2025, Europe may have to absorb up to 100 million refugees fleeing natural disasters, in addition to refugees from humanitarian crises, and labor migrants. This won’t be merely a European problem, it will affect Russia as well. How can the country prepare? How can it avoid the mass xenophobia that could arise in response to the refugee influx? What will happen to the regime in this case?

Another big-picture problem is Russia’s aging population. By 2030, Russia will have as many pensioners as it has able-bodied workers, which will bring about the collapse of the pension system. In any event, the pension system as we know it today will cease to exist.

A further trend is that as the state becomes more self-sufficient and indifferent to the plight of its citizens, there is less assistance from the top and relationships in society become more horizontal.

In other words, Russian civil society won’t stop helping the destitute, sick, and uneducated even if all NGOs are declared “foreign agents.” There will be more self-organization. New centers of legitimacy will emerge, not to challenge the state, but to fill the gaps where it is absent. Is the state ready for such developments? What are its thoughts in this regard? Most likely it has none.

In order to understand how to live better in the future, we should first think about what kind of future we don’t want to see—to imagine not the Russia we want to see in 2030, but the one we don’t want to see.

Russia’s current economic, political, and mental crisis is so deep that we need to start from the negative. No modernization, no significant change, including in the economy, is possible within today’s political framework with all of its political restrictions.

Gorbachev’s perestroika failed insofar as it was boxed in by the narrow parameters of socialism, but it did succeed in establishing a vector of possible development. And, like all other Russian modernizations, it started from the top. There are no other options. Let me put it even more cynically and definitively: Would there have been change if no one had permitted democracy and glasnost? The answer is, no.

In this age-old drama, the people mostly just stay silent, as at the end of Pushkin’s play Boris Godunov.

At best, members of the large social group that we could call the “post-Crimea majority” merely open their mouths to shout out “Right decision!” Even the truckers’ protests didn’t get beyond feeble attempts to hold to account secondary figures such as oligarch Arkady Rotenberg or Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev while they appealed to the president for help.

So, as long as Russia’s social protests are directed not against the system but in appeal to a higher authority, the only change will come from a minority in Moscow. The decisionmaking minority that craves modernization has to be at the very core of the regime, in the Kremlin and the Old Square, the headquarters of the presidential administration.

In the meantime, everyone is in waiting mode. No one knows how long it will be before the regime and society emerge from the waiting room.

About the Author

Former Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Kolesnikov was a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- How the Putin Regime Subverted the Soviet LegacyCommentary

- Putin’s New Social JusticeCommentary

Andrei Kolesnikov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya