Tatiana Stanovaya

{

"authors": [

"Tatiana Stanovaya"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

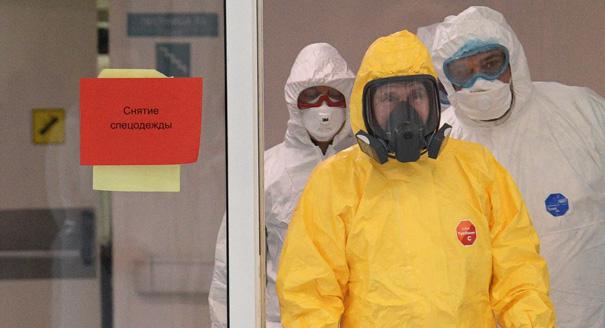

Source: Getty

Government by Proxy: Putin’s New Appointees

The appointment of a new head to Russia’s development bank VEB is an example of a new technocratic shift to deal with the economic crisis. These technocrats are generally proxies for powerful figures in the elite. Eventually, they could become an elite of their own.

The change at the top of Russia’s state-owned development bank, Vnesheconombank, is also a sign of a shift in the way the country is governed. Professionals are being called upon to fill top government jobs.

It is not that the elite wants to surrender power. Instead, in a time of economic turbulence, they are sending in proxies to do jobs, rather than getting involved themselves. The proxies are not afraid to accept responsibility and be the bearers of bad news, and they are easier to hold accountable. But in the process they may acquire political power themselves.

Two recent appointments illustrate the trend. Sergei Gorkov has been recruited to lead Vnesheconombank (VEB), while Oleg Belozerov has replaced the long-standing head of Russian Railways, Vladimir Yakunin.

Sergei Gorkov, an energetic 47-year-old who was deputy chairman of the commercial bank Sberbank, has been trusted with the job of house-cleaning at the debt-ridden VEB. Gorkov has had a varied career. He has a law degree, joined the security services, worked in Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s oil firm Yukos, but then redeemed that black mark on his career by doing valiant service at Sberbank.

This is not the kind of appointment that President Vladimir Putin would have made in his earlier years. Before, Putin’s strategy was one of expansion. The goal was to dislodge members of Boris Yeltsin’s elite, bring governors to heel, win control over major companies, build state corporations, and pump them up with assets and resources.

The main qualification for office was loyalty. That was controversial as professionalism was regarded as a lower priority than being “one of us.” But Putin dismissed the objections because he cared more about creating a “politically responsible elite” that shared his vision of Russia’s place in the world. Back then, nothing was more likely to jumpstart a career than personal acquaintance with Putin.

When this expansion of appointments had reached its limits, a different kind of expansion began as each of Putin’s protégés, whether in government office or at a state company, began to maximize his access to resources. But with the onset of the new economic crisis in Russia, it became clear that resources were finite. That realization sealed the fate of Vladimir Yakunin, who was boss of Russian Railways for a decade but lost his job last year. Yakunin was insatiable for subsidies and unable to manage the railway system effectively. When Russian Railways became a liability for Putin, Yakunin became a liability for Russian Railways.

The case of VEB is more complex. It was selected by the Kremlin as the purse for financing projects that would advance Russia’s grandeur. But it was later criticized for issuing loans it knew would never be repaid, including at least 240 billion rubles allocated for construction projects for the Sochi Winter 2014 Olympics and 496.6 billion rubles lent to unnamed Russian investors for iron and steel enterprises in Ukraine, especially in the Donbas.

VEB’s boss, Vladimir Dmitriev, was not a friend of Putin’s. He was a hired manager who was so obedient that he did not dare to ever contradict the Kremlin or deliver any bad news. Like many in Putin’s entourage, Dmitriev was motivated more by the interests of the president than by those of the institution he ran. That created a paradox. Putin wanted good news, but he also needed for everything to function without his hands-on control. After all, he has global issues to worry about, like Ukraine and Syria.

Once upon a time, the Kremlin just threw money at problems. But a full-scale government rescue of VEB would require 1.34 trillion rubles, in other words, $19 billion or 1.7 percent of Russia’s GDP.

For three months, the government brooded over how to get those billions. It would be possible to find the money, of course, but it would once again end up being managed by the unimpressive Dmitriev.

Hence the appointment of Sergei Gorkov. Asked whether VEB would be reformed, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that he is the wrong person to ask this question. The Kremlin is stepping back, VEB is in good hands, and Putin does not have to listen to any more bad news.

The change at VEB raises questions that are relevant to other Russian institutions. Will the new boss be willing to contradict the Kremlin and deliver bad news? If VEB pursues its actual mandate of creating the conditions for economic growth and stimulating investment, will the government at least not stop it from doing so? It is difficult to attract investors to a country where the authorities view business ownership as a special privilege and not a legally protected right.

The appointments of Gorkov to VEB and of Oleg Belozerov to run Russian Railways, reflect a wider shift of the balance of power toward professionals. These technocratic ministers have been keeping a low profile but getting a lot done.

Energy Minister Alexander Novak has suddenly appeared on the boards of Russia’s giant energy companies, Gazprom, Rosneft and Rosseti. Trade and Industry Minister Denis Manturov has assumed control over import substitution policy. Minister of Communications Nikolai Nikiforov launched the long-awaited Postal Bank. Deputy Prime Minister Yury Trutnev, who is also responsible for the Far East, showed up at the Davos World Economic Forum to promote investment in his region.

At the same time, influential players close to Putin are choosing to wash their hands of tough problems and working through lesser-known proxies. This is the case with the new railways chief Belozerov, whose appointment was pushed by Arkady Rotenberg, an oligarch and friend of Putin, and presidential aide Igor Levitin.

Overall, fewer Russian officials are willing to take public responsibility for their record, because that carries political risks. Those players who believe they can wait out the time of crisis are doing just that. The priority for them is to hold on to what they have. But for every political heavyweight there are dozens of “workhorses” who have nothing to lose. The current crisis gives them a chance to shine.

Moreover, what is temporary now could become permanent. The people who are entering the stage right now look like interim agents, proxies for major politicians and oligarchs, but tomorrow, they could become the new post-crisis elite. After all, many of the current political players also began as technocratic managers.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Tatiana Stanovaya is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Signs of an Imminent End to the Ukraine War Are DeceptiveCommentary

- Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Finally in Sight?Commentary

Tatiana Stanovaya

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya