Andrei Kolesnikov

{

"authors": [

"Andrei Kolesnikov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

Don’t Rock the Boat: How Long Can Putin Avoid Capsizing?

Some Russian experts are predicting that the current Russian regime will last another ten years. Change is inevitable, but no one can forecast what form it will take. In the short term, the trend is for inertia and no change.

What will the Russian political landscape look like a decade from now? Is Russia slipping back to the Soviet past or evolving toward greater authoritarianism and aggression? Are those predicting revolution right to see the nucleus of change in civil activism and a new wave of democracy in labor protests? For all the differences in opinion, there is no doubt that a political transition is looming. The question is when and what shape it might take.

The number ten is being thrown around in Russian political discourse more and more often. Former oil tycoon and Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky thinks that the current regime will endure for about ten years. A recent report from the Moscow Higher School of Economics also talks in terms of this time frame, particularly in connection with the raised retirement age and pension reform.

Election campaigns are still important to the legitimacy of the regime. The system expresses the will of the majority while delegitimizing the minority and depriving it of any right to representation. In September, the same four parties currently in parliament will again pass the electoral threshold to win seats there. New political players—more aggressive and forged in the primaries of the ruling party, United Russia—will protect the regime as it prepares for the presidential election of 2018. Vladimir Putin is bound to win that election given the prevailing confusion and political apathy in the country, as well as Russians’ lack of hope for a bright future.

So this would certainly be the right time for transition, but how might it be navigated?

Those who buy into the ten-year theory see it this way: two more years leading up to the 2018 presidential elections, six years of Putin’s next term, and finally two years for a transition in the post-Putin era, ending in the triumph of democracy. Over this period, the leaders of the transition—figures such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky and former finance minister Alexei Kudrin—could lead Russia to free elections and a system that allows for the transfer of power.

The trouble with this position is that the regime has no capacity for liberalization and democratization, and it would be naïve to expect this even in the next political cycle. In the run-up to elections and amid an economic depression, the government has to sustain patriotic “Great Power” sentiments and feed the public hunger for the appearance of progress while opening up a domestic front against the opposition “fifth column.”

This is why all talk of government strategy really boils down to discussions of short-term measures—technocratic moves that have no effect on Russia’s political or economic model. Even Kudrin, who has the reputation of being a reformer, is not expected to come up with a revolutionary plan but simply to make quick, nuts-and-bolts economic changes that can deliver an immediate payoff. Efforts are being concentrated on figuring out a way to tweak economic policy in order to pull GDP growth back up to the levels of the early 2000s and win back the hearts and minds of the middle class without undermining the foundations of the autocratic political system.

Yet if Russia is to become investment-friendly, it must change its political regime and its “fusion” ideology—the cocktail of conspiracy theories, eternally bruised national pride, and justifications for a system where “power equals property” and “property equals power.” As it stands, the government’s entire economic policy is essentially a quest for higher oil prices.

Any unstable system that fears extinction puts on a big show while cowering in private. The Putin regime has surrounded itself with a National Guard and a safety net of faithful oligarchs who come with an emergency budget for throwing money at problems rather than solving them. The regime’s legitimacy relies on the heroic past of the country—or, to be precise, the heroic past of a different country: the USSR. Domestic policy is ultimately reduced to historical policy and any war becomes a “war of remembrance.” Even Crimea was annexed first through nostalgia and only later through coercive diplomacy. Nostalgia and the desire to tame history have become the means of legitimizing power.

Moreover, in a personalist political system, the key persona matters. Vladimir Putin could seek reelection yet again in 2024 if he fears for his life and health, or for the well-being of the greater “family,” whose composition will inevitably change over the next decade.

In this scenario, there will either be a direct and brutal fight for power, or a transition. The particular way this happens might range greatly—from infighting among possible successors to a plot by them with a chosen transition figure.

It is true that Putin’s departure would not guarantee immediate well-being and a “happily ever after.” His successors could be extremist nationalists—compared to certain members of his retinue, Putin already looks like the very embodiment of rationality. However, history shows that transitions usually lead from rigid authoritarianism to liberalization, whether mild or more radical (for instance, the progression from Stalin to Khrushchev or from Brezhnev-Andropov-Chernenko to Gorbachev). The specific individuals matter, but the consensus—both within the elite and civil society—generally leans toward change in such situations.

While the debate about Russia’s direction rages on, inertia often ends up as the prevailing trajectory, especially when the autocrat and the public have a common interest: “Don’t mess with anything so that things don’t get worse.” And everyone nervously eyes the oil price. It is naïve to think that this passivity cannot remain dominant for many years. It certainly can. For now at least, the government, the business community, and the general public are satisfied with Russia’s flawed institutions, even in spite of their underlying discontent.

About the Author

Former Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Kolesnikov was a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- How the Putin Regime Subverted the Soviet LegacyCommentary

- Putin’s New Social JusticeCommentary

Andrei Kolesnikov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

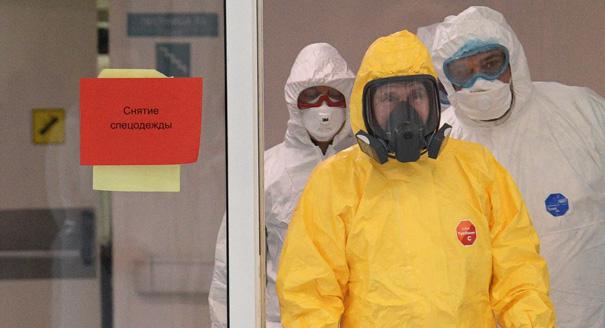

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya