In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

{

"authors": [

"Richard Sokolsky",

"Aaron David Miller"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Middle East",

"North Africa"

],

"topics": [

"Democracy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

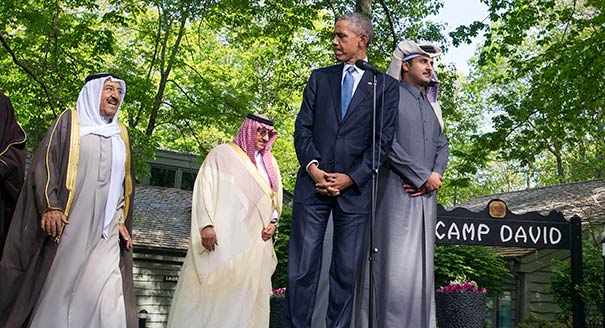

Source: Getty

U.S. interests and values, particularly when it comes to transforming the governance and political institutions of other countries, are almost always at odds with one another.

Source: American Interest

The great inside-the-Beltway think-tank sweepstakes is in full swing to see who can come up with the next big foreign policy idea for a new administration. After years of setbacks and disappointments, a hearty and familiar quadrennial is trying to make a comeback: the notion that the promotion of democracy and human rights should be the key organizing concept for U.S. foreign policy.1

It’s an inspiring and noble sentiment. But it is also a deeply misguided one.

Between the two of us, we have almost sixty years of experience working for Republican and Democratic administrations. And one lesson we’ve learned is that U.S. interests and values, particularly when it comes to transforming the governance and political institutions of other countries, are almost always at odds with one another. Not only does America lack the capacity to reconcile them, but it also may not always be prudent to try.Here’s why. First, American exceptionalism, particularly when it comes to exporting our values and way of life to others, stops at the water’s edge. The values we proclaim may well be universal in the abstract, but they are also a unique product of our history, geography, and political system. They are not made for export.

If the past 25 years of U.S. foreign policy demonstrates anything, it is the limits of America’s power to pursue transformational change in a cruel and recalcitrant world. Trillion-dollar social science experiments based on idealized conceptions of the Middle East have resulted in thousands of lost American lives, many more crippling injuries, and the shattering of the U.S. image of competency and credibility on the international stage. It is the height of naivety—however well intentioned our motives may be—to believe we can repair a region that lacks the leaders and institutions and sense of responsibility required to own up to, let alone resolve, its problems. And it is stunningly arrogant as well to believe that the rest of the world is eagerly waiting for our “City on the Hill” lectures and pronouncements about how they should organize their politics and societies.

Second, this magical thinking—that either through persuasion or pressure the United States can shape or influence in any fundamental way how other governments treat their own citizens and minorities—also reflects a galactic misunderstanding of authoritarianism. Whether it’s the acquiescent authoritarians like those of Saudi Arabia or the adversarial ones such as those ruling Iran, the prime objective of the rulers is to guarantee their own tenure and literal survival. U.S.-fostered democracy promotion threatens the system that perpetuates their power and privileges. Convincing these elites to preside over the dismantling of this system is asking them to commit political suicide.

Third, human rights doctrines that seek to straitjacket the United States into behaving consistently deny a great power the flexibility it requires to deal with the world as it is. And foreign policy in that world is necessarily filled with inconsistencies and anomalies that can’t be reconciled with cookie-cutter slogans that don’t take into account diverse and singular U.S. interests. The United States supported a so-called Arab Spring in Egypt and Tunisia, but would we want to encourage an Arab Spring that led to massive unrest and instability in Saudi Arabia or Bahrain? America invaded Iraq to overthrow an evil dictator and then occupied it in an effort to help transform Iraqi political and social institutions—with disastrous effect. Is the United States then either obligated or categorically prohibited from invading and occupying Libya and Syria, too?

Fourth, it is neither virtuous nor smart to articulate unrealistic doctrines or unattainable goals that allow the gap between our rhetoric on democracy and human rights and our actions to become so large that our credibility is swallowed by the void separating the two. The Obama Administration fell into this trap with the President’s Cairo speech in 2009, its repeated calls for Assad’s removal, and the declaration of the President’s red line on Syrian chemical weapons in 2013. Given the extreme difficulty the United States has experienced in spreading democracy, the solution to closing this gap is not to double-down on our democracy commitments but to temper our ambitions and act with greater restraint.

The spread of democracy is in the U.S. interest. John McCain is right: Our values are ultimately our interests. But we need to promote them in more measured ways and with the lowest of expectations. As one democracy expert has observed, the most effective approach is to pursue “good enough governance,” which prioritizes security, the delivery of basic services, and economic growth over the promulgation of democratic practices, which the United States has zero chance of implementing.2 Such outcomes will often fall short of our high-minded rhetoric. They will be neither pretty nor perfect nor heroic. But it is an approach that may well be better suited to the grim and stubborn realities that define the world in which we actually live.

1 See, for example, “U.S. Must Put Democracy at the Center of its Foreign Policy,” FP.com, March 16, 2016.

2 See Stephen D. Krasner, “Autocracies Failed and Unfailed: Strategies for Good Enough Governance,” Democracy Digest, March 16, 2016; and Stephen D. Krasner and Amy Zegart, “Pragmatic Engagement,” The American Interest Online, May 4, 2016.

This article was originally published in the American Interest.

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Russia and Eurasia Program

Richard Sokolsky is a nonresident senior fellow in Carnegie’s Russia and Eurasia Program. His work focuses on U.S. policy toward Russia in the wake of the Ukraine crisis.

Senior Fellow, American Statecraft Program

Aaron David Miller is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, focusing on U.S. foreign policy.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

With the White House only interested in economic dealmaking, Georgia finds itself eclipsed by what Armenia and Azerbaijan can offer.

Bashir Kitachaev

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh