Tatiana Stanovaya

{

"authors": [

"Tatiana Stanovaya"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

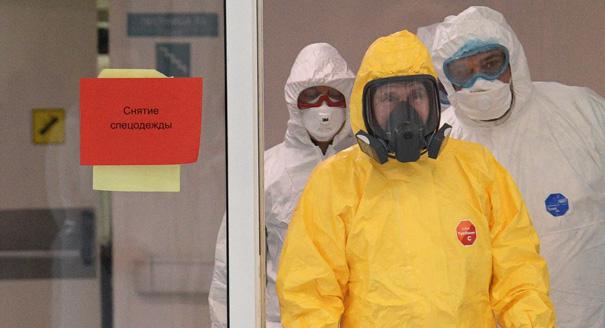

Source: Getty

Opposition From Within: Russia’s New Counter-Elite

In political systems that block change through elections, the main guarantee of a regime’s stability is its capacity to absorb a potential counter-elite. At the moment, the regime is preventing any such renewal from occurring. Yet a counter-elite is in the process of formation nonetheless—one that can eventually take Russia in a new direction.

Observers of the Russian political scene are constantly looking for clues as to where political change will come from. At a time when Russia’s “systemic” opposition, which is represented in parliament, is widely perceived as compromised, there is a common belief that the only viable alternative to the current ruling class will come from the “non-systemic” opposition, which does not play by the rules set by the Kremlin and does its politics on the street.

However, there is good reason to believe that the observers are looking in the wrong place, and that real political change in Russia will eventually come from a counter-elite that forms within the current regime.

In the post-Soviet world, existing elites have rarely been replaced by outside forces. Instead, the pattern is for disgruntled members of the ruling elites to break away and counterpose themselves to the existing regime. A classic example of this phenomenon is Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, in which Viktor Yushchenko, who had been a prime minister under President Leonid Kuchma, called for the overthrow of the ruling elite. This type of transition is only possible, however, with the backing of major business interests, regional officials, or prominent political groups.

By this logic, it is likely that those who will come to power in an elite rotation in Russia are people who already hold high-ranking positions in the current regime and are well integrated into the ruling class. It needs to be emphasized that we are not talking about the collapse or overthrow of the Putin regime. For a counter-elite to crystallize, it is only necessary for the regime to weaken considerably.

A key role in any future transition will be played by those in government whom we can call technocrats. These are individuals, ranging from middle-ranking bureaucrats to ministers and to the heads of parliamentary committees, who are competent professionals and display no conspicuous political ambitions of their own. This description fits most members of the current government—in contrast to those who served in the governments up until 2012.

The neutrality of these bureaucrats could allow them to swiftly and seamlessly transition into the counter-elite when the time comes.

Internal conflicts and disputes within the government are getting more frequent. That brings back memories of the Yeltsin era and the 1990s, when Russia’s ruling elite was in an almost permanent state of crisis and riven by disputes between different powerful groups. Based on that experience, we should not be surprised if in the future those whom we hear today expressing their loyalty to Putin transition into being the Kremlin’s opponents tomorrow.

Another way of describing this phenomenon is to say that a large number of those who serve in the current Russian establishment are “decorators” who help keep up the appearance of Russia’s “decorative democracy.” Increasingly, many of these individuals feel slighted by the Kremlin and feel that it shows no appreciation for their efforts. For example, when the Kremlin decided that it needed to revamp the Duma, more than half of the members of parliament from the ruling party ended up with no party support or financing for the election.

Those who were denied electoral victory in order to clear a path for new Kremlin favorites have not lost their political ambitions and are still looking for alternative paths of advancement. One of the main problems United Russia faced last year was that its own members had jumped ship to join the systemic opposition.

A new section of the elite is forming, which believes that “traditional values” may be more important than loyalty to the president and might in the future advocate “Putinism without Putin.”

The loyalty of business elites to the Kremlin is also provisional. We have gotten used to the notion that Russian business is fully loyal ever since 2003–2004, when it took Putin just one year to convert the country’s politically powerful oligarchs into mere businessmen who put their money only where the authorities allow them to.

Yet large sections of Russia’s top businessmen made their fortunes in the 1990s and feel no obligation to Putin. Businessmen are pragmatic and unsentimental. Corporate decisionmakers adjust to national trends and prepare for all scenarios, including a change of elite. We need only recall the intense interest that Alexei Navalny registered in business circles in 2011–2012. We can expect that if the rules set by the current regime begin to cost business billions in lost profits and hundreds of unrealized projects, then those who are currently pragmatic will begin to dream about regime change.

Another headache for the Kremlin is presented by the diverse leaders of Russia’s far-flung regions. While the current regime has full control of federal politics, it is not just difficult but even dangerous to find a strong leader for each region. After all, a strong politician with high levels of electoral support will be harder to control. What Moscow needs is hard to deliver: effective regional managers who can be painlessly removed if things go wrong.

Recently, the Kremlin has been appointing as governors not strong managers but men associated with the security services and conspicuous only by their loyalty. This attempt to simplify and strengthen governors’ subordination to Moscow will only result in more mistaken and dangerous decisions at the regional level.

If federal power gets weaker, the overwhelming majority of the regional political establishment will end up in opposition to Moscow. Literally the whole of the regional elite, with the exception of those with personal ties to the president, can potentially turn into a counter-elite.

Where do these trends leave Russia’s long-suffering non-systemic opposition, which still harbors ambitions of dislodging President Putin? Paradoxically, despite their capacity to effect political change, it is they who are least likely to form a new counter-elite. The kind of leaders who can generate street protests are too dangerous and unpredictable, and those who possess money and power will do everything to leave them on the margins of political life.

And yet despite all its problems and its miserable showing in the last parliamentary elections, the non-systemic opposition can also help form the future ruling class in Russia. That will occur not through electoral victory but through the growing personal prominence of certain individuals—something that exiled oligarch and opposition leader Mikhail Khodorkovsky has acknowledged. A new era will begin when the non-systemic opposition becomes systemic and the Kremlin is no longer able to bar it from elections because it fears a political explosion.

This is not a matter of ideology. As a change of regime gets closer, ideological labels will take second place to pragmatic considerations and connections to the man who constructed the system, the president. Many observers fall into the trap of identifying liberal members of the elite such as Alexei Kudrin or Anatoly Chubais as a potential counter-elite and alternatives to Putin. Yet even the opponent of Putin who has the strongest ideological objections to the current president may at the critical moment end up being more pro-Putin than Putin’s inner circle.

Ultimately, in political systems that block change through elections, the main guarantee of a regime’s stability is its capacity for renewal from within. That capacity depends on how well the system can absorb a potential counter-elite. At the moment, the regime itself is cracking down and preventing any such renewal from occurring. Yet a counter-elite is in the process of formation nonetheless—one that can eventually take Russia in a new direction, whether that be toward liberalization or a tougher form of authoritarian rule.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Tatiana Stanovaya is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Signs of an Imminent End to the Ukraine War Are DeceptiveCommentary

- Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Finally in Sight?Commentary

Tatiana Stanovaya

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya