There is an old Soviet joke: Lenin proved that the country can be governed by a cook, Stalin—that it can be governed by a single person, Khrushchev—by a fool, and Brezhnev—that it doesn’t need to be governed at all. As the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky said, it’s a somewhat barbaric way of looking at things, to be sure, but…

It may be accurate to describe Russia’s current political system as authoritarian, but in doing so, we greatly exaggerate how controllable the processes of governing really are. In reality, the ruling elites are concerned with only one thing: their own survival on the brink of a new political cycle signaled by the 2018 presidential election. Ordinary people, meanwhile, are concerned with surviving a lasting depression.

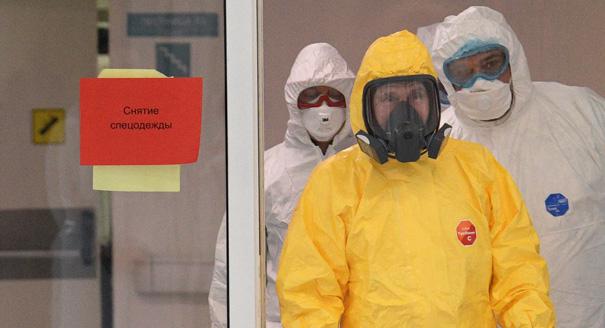

So everyone is concerned with themselves. Some pretend to rule, others—to be ruled. They even come together around an army, navy, and flag—personified by the image of the supreme commander in chief. Television is the main source of information, and the workers are told how they’re supposed to think and reason via the statements of Dmitry Peskov, Maria Zakharova, and Igor Konashenkov: the respective spokespeople for the Kremlin, the Foreign Ministry, and the Defense Ministry. This state of bad equilibrium could continue indefinitely.

Maybe this kind of authoritarianism truly is hybrid, including as it does aspects of democracy. These days, Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, authors of the 2010 book Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War, are quoted more than Marx and Engels were in the age of strict historical materialism. Just like the Moliere protagonist who was unaware that he spoke in prose, so too are we unaware that we live in a hybrid state. But, comrades, does that mean that we should get used to it?

Wasn’t the late USSR a hybrid? It certainly wasn’t pure totalitarianism. And does President Vladimir Putin really possess absolute power? What about the ceaseless toil of the vigilant masses and enterprising deputies, and the investigative and regulatory authorities who sometimes ignore Putin? Don’t all these people also help to make everyday life unbearable? Is the autocrat as powerful as we think when the personal opinions of several friends are no less important to him than the influence on Boris Yeltsin of his bodyguard and adviser Alexander Korzhakov was during a regime that we generally accept as democratic?

Western political scientists often hold forth about the rise of illiberal democracies, though they are hardly a new phenomenon. Franco’s regime and the national obsession with him in his “organic democracy,” the USSR, and the so-called people’s democracies in Eastern Europe have all been here before. The majority of Soviet citizens genuinely believed that they had unprecedented freedom under a socialist democracy. Current sociological studies show that the number of people who think they live in a free, democratic state only increases as the screws are tightened.

Modern Russia is a giant, post-imperial nation that is suffering from monstrous, post-imperial phantom pains along with the desire to reattach some of its lost limbs. And in many ways, we are not even post-Soviet, but purely Soviet people who just happen to be living in anti-Soviet circumstances. And when a Soviet/post-Soviet person suddenly notices the specter of the USSR in Russia’s government—inflated military power, the exportation of oil and fear—and realizes that, once again, the world is afraid of us, they feel good, because it’s something familiar.

So much has been written about Putin’s 80 percent approval rating. Maybe there is no longer a Putin majority, but only a Putin minority: does anybody have a real benchmark? But by virtue of mass apathy toward what’s happening at the top, this minority will be enough for the same rulers to hang on after 2018. The strategy of giving up food imports in exchange for Crimea continues, and Crimea has become a symbol of our recovered sovereign might.

But despite the sometimes uncanny similarities to the late Soviet era, such comparisons are incorrect. Firstly, back then there was colossal demand for change, and a leader appeared who was ready to initiate those changes. There was massive support for reforms, and the overripe public woke up quickly and began to develop ahead of the state.

This sort of thing doesn’t exist nowadays, although I do hear almost daily that “there has never been such demand at the top for a strategy of change”—except, presumably, in 2000 with German Gref’s program of economic development, in 2008–2011 with the Institute of Contemporary Development programs, and under the government’s innovative development strategy through 2020. In addition, the conditions of perestroika were unique, and cannot be replicated.

Secondly, despite incessant state intervention, the country has a market economy, which, embodied by an upscale ice rink next to Lenin’s mausoleum on Red Square, is in itself enough to save our ugly, hybrid system from a hungry death.

In one sense, it’s completely rational for the elites to avoid change, although it betrays their inability to look beyond the horizon. They are not frightened enough by the current stagnation to initiate changes in the system for their own sake. But what they do fear greatly is losing everything all at once by pulling some crumbling brick out of the system, causing the whole construction to come crashing down.

As for the masses, many—if not the majority—are simply afraid that things will get worse as a result of change. For that reason, if they’re ready to concern themselves with anything, it’s with negative adaptation: anything that increases their chances of survival. And anyway, what do the so-called reformers have to offer them? There was a hospital within walking distance, but now it’s been “optimized”—closed. There was a school, but now it’s gone. There were unofficial salaries on which people could live during a recession, but the authorities came along and made everything official. There was a job going, but now they say a robot is going to do it, for scientific progress has arrived, together with high-performance jobs.

The country is frozen in a brittle hybrid of bad equilibrium, and it’s afraid to even draw breath. Perhaps new U.S. President Donald Trump will help? But that line of thinking only brings us to another Soviet joke: During a recent party congress, the announcer says, “Everyone stand! We’re wheeling in the Politburo!”