Andrei Kolesnikov

{

"authors": [

"Andrei Kolesnikov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

Yeltsin’s Overcoat

Ten years after Boris Yeltsin’s death, we’re only beginning to grapple with the legacy of his transformative presidency.

“Well, I’ve seen this before,” Shamil Tarpishchev sighed on November 25, 2015, the day of the opening of the Boris Yeltsin Center in Yekaterinburg, which is designed to look like the first Russian president’s Kremlin office. Either Tarpishchev, Yeltsin’s personal tennis coach, was passing through the museum for a second time, or he was transported back to the 1990s.

In all likelihood, it was the latter. A plane full of current and former officials—the entire 1990s elite—descended on Yekaterinburg for the opening, at which Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Medvedev, and Yeltsin’s wife Naina gave speeches honoring the late president. For a moment, it seemed that a truce had been struck among the attendees; the Kremlin’s war on the Yeltsin era had been temporarily put on hold.

Yeltsin died ten years ago this month, and to younger Russians—as well as to the political technologists who built the current regime by differentiating it from Yeltsin’s—his presidency seems impossibly far off.

Russians do remember Yeltsin, however, though not terribly fondly. It’s like the anecdote about the two old clowns who are not invited on tour. One says “They forgot about us,” while the other says “No, they remembered us.” A former assistant to Yeltsin, Georgy Satarov, who is currently one of Putin’s opponents, remembered this very joke on the November 25, 2015, plane to Yekaterinburg.

For many years, the Levada Center has run a survey in which it asks respondents, “Do you think the Yeltsin era brought more good or bad?” Responses over time provide important insights into Russian political psychology: in 1999, when Yeltsin’s presidency was coming to an end and Russia was in the throes of default, and when a young blonde officer from the KGB with a brusque manner of speaking was ascending to power, 72 percent of Russians said that there had been more bad than good under Yeltsin.

But by 2012, old grievances had been forgotten, and this number had fallen to 55 percent. Between 2012 and 2016, 68 percent of Russians said there had been more bad than good under Yeltsin—in part a reflection of the surge in national pride that accompanied the annexation of Crimea. When life is good, Russians tend to remember the past as being worse.

Another Levada Center survey asked Russians whose policies had been better, Gorbachev’s or Yeltsin’s. In 2016, respondents were nearly split down the middle. Yeltsin and Gorby, despite being irreconcilable political opponents, will go down in history together as a duet. They reflect the way Russian high politics is seen as a pendulum swing: Lenin is bad, Stalin is good, Khrushchev is bad, Brezhnev is good, Gorbachev and Yeltsin are bad, and Putin is good. In short, leaders who introduce “thaws” are bad, while those who bring about “freezes” are good.

Thus rocks the cradle of history in which Russians doze, failing to recognize Yeltsin as the tsar-liberator he hoped to be. And indeed, Yeltsin was not a model democratic politician. But then again, where could such a figure have come from in the Soviet Union, where freethinking was punishable by exile in the freezing north or execution?

Still, Yeltsin was a measuring stick: a Russian politician should be tall, handsome, capable of grand gestures; he should be occasionally funny, silver-haired, and strong but intelligent. Who but Yeltsin could have garnered the support of millions of people who had been awakened—paradoxically—by his opponent, Gorbachev? Who but Yeltsin could have provided political cover for those like Yegor Gaidar trying desperately to reform Russia? Only Yeltsin, who massively damaged his popularity so that future generations might live better.

Putin rode into politics on Yeltsin’s back, both standing in opposition to the tumult of his predecessor’s reign and bringing with him economic ideas that had emerged thanks to Yeltsin, Gaidar, and the institutions they created. This exemplifies the kind of political schizophrenia that characterizes the current regime. Fyodor Dostoyevsky said, “We all came out of Gogol’s ‘Overcoat,’” referring to Nikolai Gogol’s story. In the same way, all of us in modern Russia came out of Yeltsin’s overcoat but feel the need to disavow the 1990s.

Still, authoritarianism a la Russe does not flow entirely from Yeltsin’s legacy or his message to the next generation of politicians to “take care of Russia.” Yeltsin left behind important democratic and economic institutions that his successors had the opportunity to develop or squander. After he left office, Yeltsin could only watch, seemingly restraining himself from criticizing his political heirs.

Ten years is not enough time to appreciate the scale of Yeltsin’s impact. Just as Moliere’s Monsieur Jourdain didn’t know that he had been speaking in prose his whole life, the average Russian doesn’t stop to think that they are living in a country that Yeltsin created—whether good or bad.

Yeltsin was a great man in every sense of the word. On June 12, 1991, 57 percent of Russians, or 45.5 million people, voted for Yeltsin. They expected him to work wonders, but instead he gave them the tools to work wonders themselves—something not everyone wanted to do.

About the Author

Former Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Kolesnikov was a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- How the Putin Regime Subverted the Soviet LegacyCommentary

- Putin’s New Social JusticeCommentary

Andrei Kolesnikov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

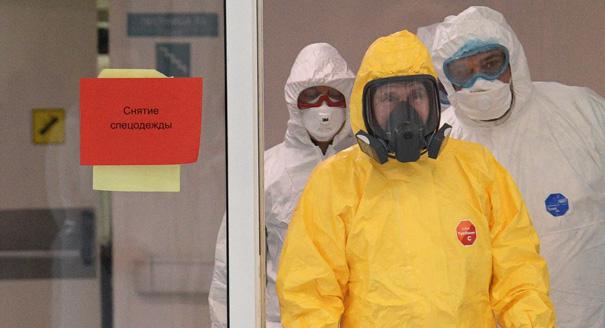

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya