Tatiana Stanovaya

{

"authors": [

"Tatiana Stanovaya"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

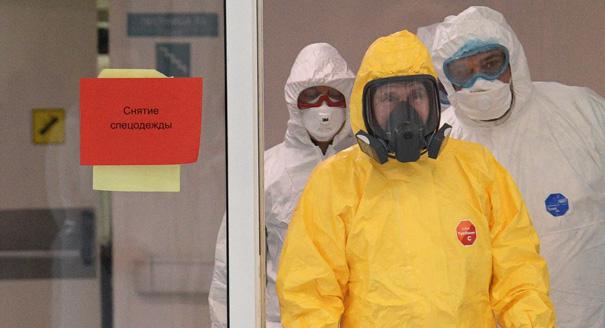

Source: Getty

Putin’s Post-Political Government

This year’s Direct Line with Vladimir Putin revealed that politics has been entirely removed from the public sphere in Russia. Government decisions are now made with zero input from the people.

On June 15, Vladimir Putin hosted his annual Direct Line call-in show on live television, fielding questions from handpicked concerned citizens across Russia.

Each year, the topics of conversation are more or less predictable. This year, the Russian president was expected to touch on Russian relations with the United States under Donald Trump; dialogue with the EU and NATO; Brexit; the growth of anti-globalist sentiment around the world; and Russia’s strategies in Ukraine and Syria.

On the domestic front, the president would discuss the protest wave spreading across Russia; the role of the opposition; the State Duma’s newfound involvement in political processes; government policy on NGOs; the growing role of the special services; and the effectiveness of the National Guard—in addition to a host of economic issues.

But Putin covered virtually none of these topics. In fact, the President chose not to address any substantive political matters during the Direct Line, making this year’s show fundamentally different from its predecessors.

Over the course of the show, Putin reduced government policy dilemmas to personal and local problems. For instance, the president treated the problem of low salaries for young teachers—the show’s first topic—as an issue that the administration of the school in question should address. In one way or another, Putin described every problem that was brought to his attention as a particular or even exceptional case in which government policy had broken down, but didn’t discuss the policy itself.

Rather than formulating any kind of broad position on important policy issues, Putin the national leader presented himself as Putin the national building superintendent: the scope of government policy was reduced to the technical elements of business management, without any thought given to long-term solutions.

Indeed, the subject of the future almost completely disappeared from this year’s Direct Line script, popping up only in Putin’s final remarks, in which the president briefly listed several vague, long-term goals, including income growth, eliminating substandard housing, and increasing productivity.

But the president didn’t say a word about how any of this might be accomplished—not because he makes no decisions but rather because the government is no longer accountable to the people. The state has entirely absorbed the public sphere, and Russians have been deprived of all agency.

In practice, this means that Russia’s political and administrative spheres are becoming hermetically sealed; because the state no longer needs to explain what it’s doing, Putin’s agenda becomes increasingly distinct from the one presented to the public.

This is probably why Putin discussed issues like the protests surrounding St. Isaac’s Cathedral and the Matilda movie only in very general terms. Putin does not believe these problems are about relations between his government and the Russian people. “We have to depoliticize the problem, forget that it exists,” he said as he voiced support for handing St. Isaac’s Cathedral over to the Russian Orthodox Church. The president’s choice of words clearly illustrates that he sees everything political as destabilizing and destructive. Even the opposition, in his view, should play an advisory rather than political role.

Putin alluded to high politics only during his Q&A session with the press after the Direct Line, when the president addressed his true “enemies,” accusing the BBC of spreading propaganda and supporting opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

Discussion during the Direct Line boiled down to problems that the regime imagines to be socially important: the future of particular companies, and pensions, salaries, and other matters that are viewed as an unavoidable social obligation that the president must fulfill. Meanwhile, he solves the real problems behind closed doors.

In this context, the timing of this year’s Direct Line is very telling. It aired much later than its traditional April time slot. The show was delayed because Putin has much more important issues to address—Syria, the terrorist attack in St. Petersburg, intensifying contacts with the United States, and a visit to France, among others. The Direct Line went on the air only when the president’s schedule allowed it; after all, such a performance requires serious preparation.

Putin’s motivation for speaking to the public is also changing: he now sees it as an act of political charity rather than as a conversation with the constitutional source of his power. The president is used to defending his political views, however critical others might be of them. He has excelled at it, and willingness to engage in an open and honest dialogue has always been part of his image. Over the past year, however, this willingness has disappeared.

Finally, the Direct Line served as a further indication that Vladimir Putin equates his legitimacy with that of the state. All forces that attempt to weaken him are automatically seen as a threat to Russia. Critics of the regime will tell you that the “No Putin—No Russia” slogan is not new. But there’s something different about the refrain now: the government is completely closed off from the public, which now plays a purely nominal role, as the regime attributes popular support to itself automatically.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Tatiana Stanovaya is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Signs of an Imminent End to the Ukraine War Are DeceptiveCommentary

- Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Finally in Sight?Commentary

Tatiana Stanovaya

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya