Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

{

"authors": [

"Andrey Pertsev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

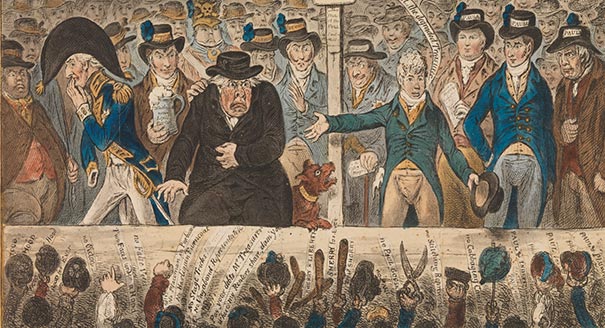

Source: Getty

Unhappy with plans to raise the retirement age, the decline in their living standards, and tax hikes, Russians can’t vote for the real opposition. Strong candidates are either not allowed to run or prefer to cooperate with the authorities by not running, while in-system parties deliberately tone down their rhetoric. Under such conditions, the protest vote becomes random: people are willing to vote for anyone but the ruling regime candidates.

The conditions in which Russia’s recent regional elections took place were extremely favorable for the federal government: strong candidates refrained from running or weren’t allowed to run, and the in-system parties composed government-friendly candidate lists for regional and local legislatures. But despite all of these precautions, we witnessed an incredibly powerful protest vote: four regions will have runoff gubernatorial elections, while in three, ruling United Russia lost to the Communist Party. To top it all off, an opposition candidate won the mayoral election in the city of Yakutsk.

The most unexpected result to come out of the regional elections on September 9 is a second round of gubernatorial elections in as many as four Russian regions: Primorsky, Khabarovsk, Khakassia, and Vladimir. This has happened only once since direct elections of regional executives were reintroduced in 2012: the Communist candidate Sergei Levchenko made it to the second round of the Irkutsk gubernatorial election in 2015 and won.

But Levchenko was a strong candidate, a State Duma member who enjoyed the support of the local business community. Those who advanced to the second round this time around had nowhere near his resources and weren’t even considered real opponents to the ruling party candidates.

LDPR State Duma member Sergei Furgal, who garnered 35 percent of the vote in the Khabarovsk region—the same as the incumbent governor—had his Duma status, campaign funds, and name recognition behind him. The other runoff candidates had none of those advantages. The Khakassia Communist Party leader Valentin Konovalov, who got more votes than the current head of the republic, is merely a municipal legislator. No one was serious about the chances of the Communist Party’s Andrei Ishchenko (Primorsky region) or LDPR’s Vladimir Sipyagin (Vladimir), but both earned enough votes to advance to runoffs against incumbent governors.

The regime’s candidates—both popular (Andrei Tarasenko in the Primorsky region) and less popular and excessively long-serving ones (Viktor Zimin in Khakassia, Vyacheslav Shport in Khabarovsk, and Svetlana Orlova in Vladimir) were clearly up against the protest vote. The voters were saying “anyone but them.” Even Vladimir Putin’s endorsement didn’t help: the president diligently met with all four and lent all the support he could.

This makes the results even more lamentable for both the heads of the regions and the Kremlin. It would be more palatable if the incumbents had been fighting against powerful and well-funded political figures, but struggling against a semi-spoiler, whose presence on the ballot was approved by none other than the incumbent, is an entirely different matter.

The regional election campaign exposes the general political problems of the government, which is currently forced to combat protest sentiment rather than individual opponents. A vote cast for an obscure candidate says one thing: people wish to demonstrate their discontent, even if it means voting for an absurd candidate like someone from the LDPR, headed by the notoriously provocative Vladimir Zhirinovsky.

In the past, regional elections faced a simple task: keep opposition candidates from winning, even if they were part of the system and loyal to the federal (but not the local) government. When gubernatorial elections returned to the political arena in 2012, the so-called municipal filter was introduced: in order to run, candidates had to receive support from a certain number of local legislators. This was used by the local authorities to keep opposition politicians off the ballot. Convenient names on the ballot provided convenient results.

This rule no longer works. The authorities may come up with a perfect list of candidates, ostensibly leaving people no choice but to vote for the regime’s pick or stay at home. But now voters may go to the polls and select any name on the ballot in protest. Just imagine how much more disastrous the results would have been if the ballots had featured recognizable and powerful names, or sharp critics of the regime.

The situation in the Vladimir region is a good illustration of the overall picture. Sipyagin, a regional legislator from the LDPR, made it to the runoff alongside the incumbent governor Orlova. Sipyagin was elected to the regional legislature on the LDPR party list, meaning it was the persona of Zhirinovsky that got him his seat. The Communist candidate, the television journalist Maxim Shevchenko, didn’t make it through the municipal filter, which means that a purely symbolic candidate forced a runoff with the incumbent.

The Vladimir election has one more telling characteristic. Acting Governor Tarasenko might not have had time to gain recognition in the Primorsky region, and Shport and Zimin have never been particularly popular in their respective regions, but Orlova was once an almost revered figure. She came from the outside and was a populist who could make promises and talk to people directly. She could pop up in any municipality, lash out at local officials, find the responsible party, and showcase it to the disgruntled public. Just a few years ago, people would take pictures with her on the street.

But the public gradually grew tired of the good czarina. The proposed pension reform dealt the final blow to her approval rating. The “people’s governor” failed to speak out against increasing the retirement age, which destroyed her political image.

The elections for regional legislatures also delivered some surprises. United Russia lost the party list elections in the Khakassia, Irkutsk, and Ulyanovsk regions, where the Communists won. The last time this happened was in the Stavropol region in 2007. Moreover, with the exception of Ulyanovsk, where the Communist Party list was headed by the popular State Duma member Alexei Kurinny, the Communists presented somewhat convenient lists for United Russia. In Irkutsk, for instance, Communist Governor Sergei Levchenko didn’t even head his party’s list.

So again, these results were shaped by protest sentiments. LDPR’s growing percentage of votes seems to lend credence to this suggestion. The party is essentially now a substitute for the long-scrapped “Against All” choice on the ballot. In nine regions, United Russia got less than 40 percent of the vote. The victory of the little-known Sardana Avksentyeva in the Yakutsk mayoral election points to the same issue: when voting for her, people were protesting the absence on the ballot of the popular local legislator Vladimir Fedorov.

So what’s going on? Unhappy with plans to raise the retirement age, the decline in their living standards, and tax hikes, people can’t vote for the real opposition. Strong candidates are either not allowed to run or prefer to cooperate with the authorities by not running, while in-system parties deliberately tone down their rhetoric. Under such conditions, the protest vote becomes random: people are willing to vote for anyone but the ruling regime candidates.

The removal of unwanted candidates only placed an additional burden on the post-election power vertical in the region. A strong in-system opposition governor-elect brings his experience and team to the office, which might be unpleasant for the vertical, but doesn’t destroy it. However, if a symbolic candidate who lacks a team and experience wins, he or she might not be easily manageable.

Another problem for the regime is possible coalitions between in-system opposition parties in places where United Russia failed to win the majority. Politicians may learn to agree among each other, but not with the regime.

Finally, to chip away at the Communist Party’s election gains, the authorities let spoiler parties such as the Communists of Russia run in some “red” regions. But the spoilers unexpectedly cleared the electoral threshold and are now eligible to nominate their own State Duma candidates, which also complicates the political system, creating space for a new bargaining process and agreements.

While trying to clear and simplify the political field, the federal center has actually made more complications. Instead of dealing with alternative structures, the power vertical is now facing chaotic protest, which can’t be resolved by traditional means: in fact, they only multiply chaos.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

The EU lacks leadership and strategic planning in the South Caucasus, while the United States is leading the charge. To secure its geopolitical interests, Brussels must invest in new connectivity for the region.

Zaur Shiriyev

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy