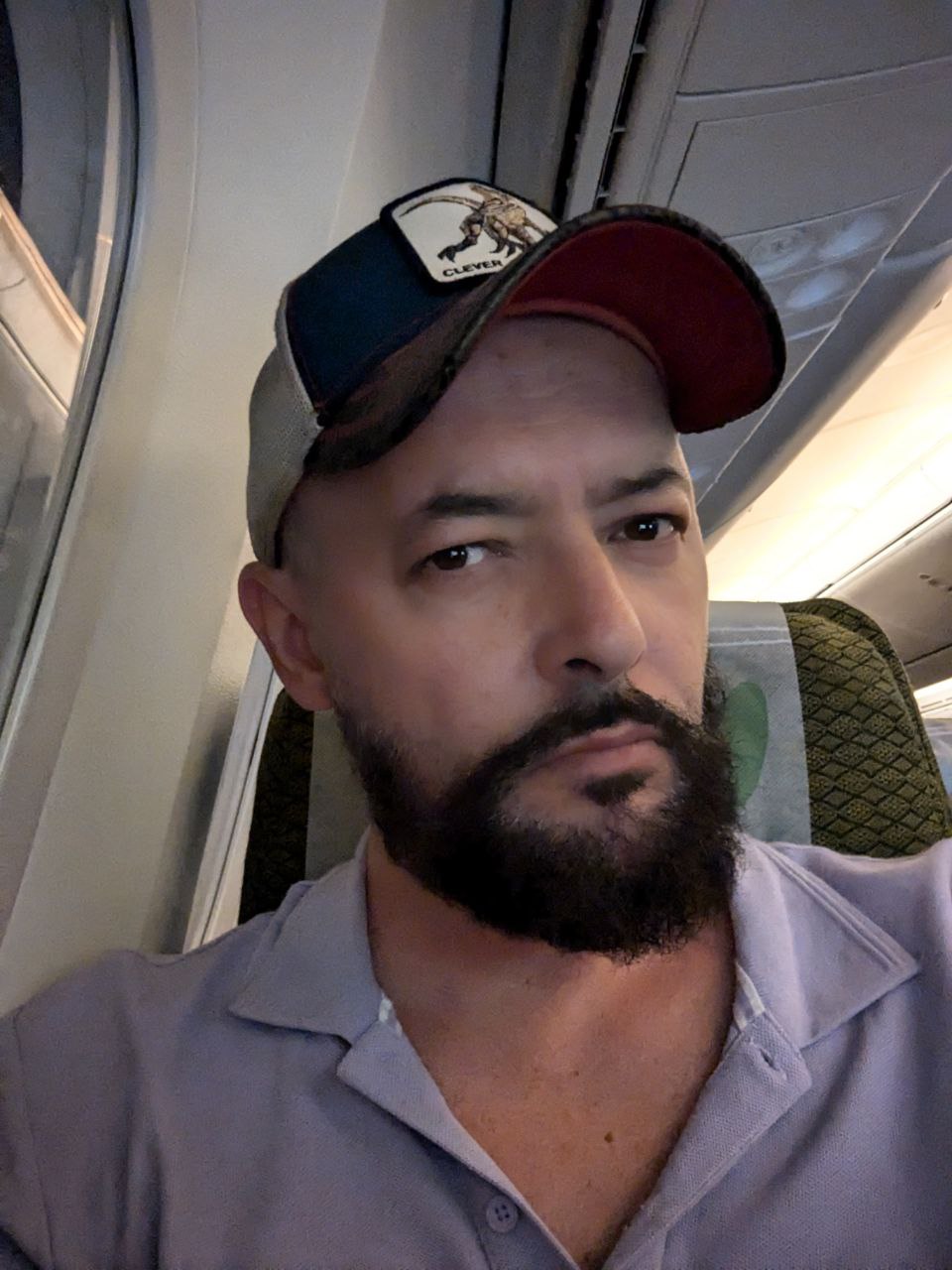

Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Baunov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Moscow’s Crisis Is Now Russia’s Crisis

By agreeing to the brutal suppression of peaceful protests about Moscow city elections, Mayor Sobyanin has submitted to collective responsibility. For Putin and the Kremlin, it is impermissible that elections can be lost. This is a message for Russia’s next parliamentary and presidential polls.

A short time ago, the mayor of Moscow, Sergei Sobyanin, seemed to have achieved something rather special.

Sobyanin had won praise for transforming Russia’s capital into a much more European city and apparently neutralized opposition by peaceful means, while also keeping the approval of President Vladimir Putin and remaining independent of the ruling party United Russia.

Now, in just a couple of weeks, this speeding ambition has flown back and hit him like a boomerang. Twice the streets of Moscow have seen the biggest protests in Russia since 2012, followed by ugly scenes of police repression and the detention of thousands of demonstrators.

What’s more, Moscow has lost its status as a special political enclave in the country. The crackdown on protest is being directed not by the mayor but from the Kremlin. Both Russia’s rulers and the opposition see the confrontation as a trial run for a bigger showdown in the parliamentary elections of 2021 and the next presidential election of 2024.

The occasion for this crisis was something fairly run-of-the-mill: the denial to opposition candidates of a chance to run in the Moscow city assembly elections. In 2014, before the last elections to the assembly, Sobyanin had secured from Putin the right to have the contests fought between individual candidates without any party lists—in contrast to the practice in the rest of Russia.

It was just like the special dispensation some powerful European cities used to receive from their monarch in medieval times. And it worked well for Sobyanin in 2014, when his favored candidates won seats in the assembly nominally as independents. It entrenched the mayor’s status as the only politician in Russia—apart from Putin himself—who was detached from the official party, United Russia, and all its problems.

This time, however, the practice led first to a procedural trap, and then a political crisis. Under the new rules, candidates not backed by a political party were required to collect about 5,000 signatures in order to register. Muscovites then watched with growing anger as pro-government candidates were registered, without actively bothering to collect signatures, while popular opposition candidates were denied registration on technical grounds.

The Moscow city authorities could have defused the problem by permitting opposition candidates to register after all. But the decision was taken at a higher level. A show of tolerance would have been a bad precedent for other regions and for the 2021 parliamentary elections. The other way was chosen—direct confrontation with the opposition.

The political demonstration held in the center of Moscow on July 27 was about more than just the city elections. The response was brutal. At that demonstration and the subsequent one a week later, protesters were beaten and around 1,000 were arrested on each occasion.

Between the two protests, dozens of opposition activists, including many would-be Moscow city deputies, were detained and charged. It was a deliberate display of raw power. One opposition figure, Mikhail Svetov, was even arrested just after he had left talks in Moscow city hall.

When Moscow Mayor Sobyanin appeared on television and expressed his full support for the crackdown, it was obvious that no cracks could be allowed to be seen in the ruling elite. Instead, they have what might be called a pyramid of responsibility. The upper levels do not want to be held responsible for repressive measures taken by lower-level officials—as happened with the arrest and then release of journalist Ivan Golunov in June. But anyone lower down the structure has to support the decisions taken at the top.

So, Moscow’s crisis also became Russia’s crisis. Both sides in the struggle understand that much more is at stake than mere participation in some municipal polls, and see this as the first skirmish in a battle for the Kremlin. Normally, the police would not have handed out brutal beatings to peaceful demonstrators complaining about the rules of admission to the Moscow city assembly. This was a message of force from the country’s rulers that this is what people will get if they want to depose the tsar and “destroy Russia.”

That in turn has energized Russia’s “non-systemic” opposition, who want to get rid of Vladimir Putin. Three weeks ago they were talking about a modest regional campaign. Now they have a more ambitious program of civic resistance across Russia. They have no clear hope of victory. But they do see a chance to disrupt the Kremlin’s plans for an orderly transition between Putin and a chosen successor, by channeling various forms of discontent: the unhappiness of the Russian intelligentsia, the economic woes of ordinary people, resentment of Moscow in the provinces, uncertainties in the elite.

The biggest loser in this process so far is Sobyanin. He is now the object of scorn of the critical Moscow middle classes. The Western diplomatic and journalistic corps, who were impressed by the improvements he had made to Moscow, are now much more chilly.

For Putin himself this is nothing less than a matter of national security. For him elections are not a mechanism for settling domestic differences; they are a direct threat to his power. His Russia cannot be defeated in a war, but it can theoretically be defeated in an election. The system demands that elections cannot be lost.

The state response has been harsher than the one that followed the protests in Moscow in the winter of 2011–2012. Then the government did not honor the political demands of the protesters, but it did meet them halfway by working to deliver the urban classes better digital services, public transport, and green space. Seven years on, that has inspired the new wave of Muscovite protesters to demand more, to build a more genuine model of Europe in their city.

The demonstrators are getting the opposite of Europe; they are experiencing a Russia that again much more strongly resembles a police state. Unlike last time, it is the government which has escalated the crisis. The authorities have responded to peaceful protests with violence, arrests, and detentions, as if a revolution was under way, more or less saying to the protesters, “You want a revolution, we are ready, let’s fight!” It is as though they are trying to protect themselves from future scenarios by doing surgery on an abscess that is not yet dangerous.

This is not a regime that has a considered strategy and a consistent ideology; it acts in response to events. The crises, threats, and successes it has experienced all leave their mark and condition future behavior. When immediate crises are over, the limits of permissible action are stretched each time. The ruling elite sees the suppression of the current demonstrations in Moscow as a kind of training exercise for putting down a future revolution. It’s an experience that they feel deeply and will remember for next time.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Baunov is a senior fellow and editor-in-chief at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

- Could Russia Agree to the Latest Ukraine Peace Plan?Commentary

Alexander Baunov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Getting Debt Sustainability Analysis Right: Eight Reforms for the Framework for Low-Income CountriesPaper

The pace of change in the global economy suggests that the IMF and World Bank could be ambitious as they review their debt sustainability framework.

C. Randall Henning

- How Middle Powers Are Responding to Trump’s Tariff ShiftsCommentary

Despite considerable challenges, the CPTPP countries and the EU recognize the need for collective action.

Barbara Weisel

- How Europe Can Survive the AI Labor TransitionCommentary

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley

- The EU’s New Industrial Strategy and Global DisorderResearch

The fear that Europe might ‘fall behind’ rival economic powers has long shaped European integration. In the present phase of global disorder, this fear has intensified.

Scott Lavery

- Does Russia Have Enough Soldiers to Keep Waging War Against Ukraine?Commentary

The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets