The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

{

"authors": [

"Dan Baer"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Coronavirus"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"Global Governance"

]

}

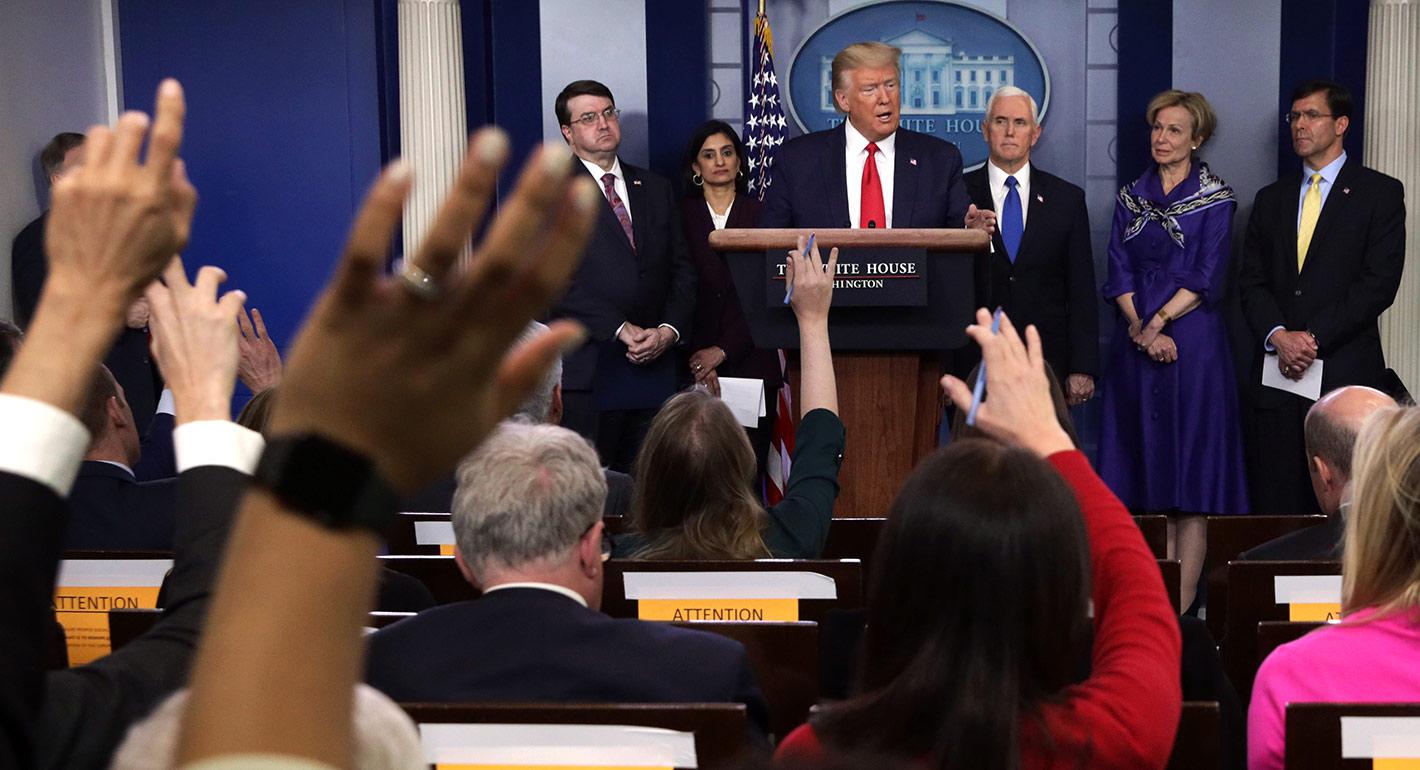

Source: Getty

Washington’s failure to lead in a moment of global crisis will have lasting effects on its stature in the world.

Source: Foreign Policy

Last weekend, the German newspaper Die Welt reported that the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump had sought to entice a German company working on a coronavirus vaccine to move its research operations from Europe to the United States. According to an unnamed German official quoted by the Berlin-based paper, the Trump administration’s intent was to have the eventual vaccine “only for America.”

It’s still unclear what exactly happened. Was there an attempt to buy the company? With private money or public funds? Trump’s new acting director of national intelligence who remains ambassador to Germany, Richard Grenell, denied the report. Jens Spahn, the German health minister, confirmed it. It seems likely that there was some sort of overture—even if it is also likely that we don’t have all the facts. As former ambassador Steven Pifer observed on Twitter, while there once was a time when a story like this—the United States sneaking around the back of a close ally to steal medicine—would have seemed unthinkable, the past behavior of the Trump administration makes it seem entirely plausible.

The story is now out there, and there has been no small amount of hand-wringing over the damage that has surely been done to the image of the United States and the U.S.-German relationship: Imagine the reaction of the German people, who are dutifully following Chancellor Angela Merkel’s request to self-isolate in order to flatten the coronavirus curve, as they read that the U.S. president was trying to buy critical medical research with the hopes of using it only for his own country. Add this to the fact that in Italy, it is China, not the United States, that is delivering medical equipment and assistance as the Italian health system bends under the strain of the pandemic. And furthermore, that Trump last week announced restrictions on travelers to the United States from Europe without prior coordination with European partners or even a word of warning. Suffice it to say that the past week has marked a relative low point in trans-Atlantic relations.

The past week also underscores two consistent failings of Trump’s foreign policy: First, that the Trump administration is lousy at preserving the trust and goodwill that is essential to sustained, cooperative relationships with other governments. And second, that the coronavirus pandemic is laying clear the folly of Trump’s “America First” theory of foreign policy—and of other approaches to foreign policy, on both the left and the right, that are premised on the fiction that the welfare and interests of the United States can be protected and defended separately and apart from the welfare of the world.

What’s so disheartening about the idea that Trump might try to poach a vaccine for exclusive use in the United States is not the craven greediness of it; it’s that it so obviously misunderstands the nature of the threat this pandemic poses. Countries need to cooperate internationally to ensure that somewhere in the world—anywhere in the world—a vaccine is discovered as quickly as possible, and ultimately we need a vaccine to be globally accessible. It is plain stupid to think that hoarding medical research that could yield interventions that would treat or protect against a pandemic would actually serve U.S. interests.

The United States needs a functioning European economy. American farmers and businesses depend on trade with the rest of the world. U.S.-based multinationals depend on foreign workforces. Pandemics can cause instability and conflict that endanger American troops and interests overseas. The United States is a global power: The world depends on the United States, and the United States depends on the world.

The response to the coronavirus might have been more efficient if it had first appeared in a country that wasn’t authoritarian and didn’t suppress news about the virus in the early weeks. And it might have been more effective if the United States were helping to lead and coordinate the world’s response to the outbreak, rather than claiming for weeks that the virus was not going to affect it and therefore was nothing to be concerned about, before pursuing a set of policies that surprised the closest U.S. allies.

When I was in government, I often wanted to tell people that they couldn’t use the words “Marshall Plan” in meetings: It seemed like every meeting about a crisis somewhere in the world had one person who would say, “What we need is a Marshall Plan for [insert country or region].” And while that trope became frustratingly predictable, it of course reflected the fact that moments of great need can be moments of great opportunity for American leadership. For a generation or more, the Marshall Plan’s intent and effects had a lasting impact on the popularity of and trust in the United States across Europe. Trump’s mismanagement of the domestic coronavirus response has been dire. America’s failure to lead in a moment of global crisis will have lasting effects on its stature in the world.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

A prophetic Romanian novel about a town at the mouth of the Danube carries a warning: Europe decays when it stops looking outward. In a world of increasing insularity, the EU should heed its warning.

Thomas de Waal

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

The risk posed by Lukashenko today looks very different to how it did in 2022. The threat of the Belarusian army entering the war appears increasingly illusory, while Ukraine’s ability to attack any point in Belarus with drones gives Kyiv confidence.

Artyom Shraibman

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum