Tatiana Stanovaya

{

"authors": [

"Tatiana Stanovaya"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Coronavirus"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

Postviral Complications: What Next for the Russian Regime?

Russia is rapidly approaching a situation in which the public will lose the right to decide anything once and for all, because the authorities simply have no remaining political will or the resources to persuade the people.

President Vladimir Putin’s announcement on May 11 of the gradual lifting of the lockdown was somewhat at odds with Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin’s worried statements about the growth in new coronavirus cases. This is far from the only example of officials providing conflicting assessments of the situation. Throughout the epidemic, the seemingly consolidated system of authority has acted with a surprising lack of coordination and balance.

There are several reasons for this disarray, and the main one is the crisis of political responsibility. When Putin distanced himself from making routine decisions and delegated them to lower levels of the state apparatus, the government proved incapable of taking the initiative and acting of its own accord: this is one of the characteristics of the technocrats who dominate the cabinet. This technocracy, combined with an absent Putin, has resulted in the government ceasing both to think in political terms and to be guided by future elections and the public mood.

The difference between politicians and technocrats is that the former orient themselves on public support, while the latter focus on the opinion of their boss, and taking the initiative may result in punishment. A professional achievement is a well-compiled report that allows figures to be manipulated to conceal any failures.

This brings key performance indicators (KPIs) to center stage: the number of hospital beds, the availability of ventilators, and medical staffing levels. The higher the figures, the better the impression made on the president, and, therefore, the rosier the official’s political future. KPIs are taking over, isolating the government from reality. Reports about successes and achievements substitute for reports about problems and failures, and this is one of the reasons for the president’s inordinate optimism.

The crisis has shown that Russia’s famed power vertical—practically the main symbol of Putin’s rule—serves only one purpose: to create a political arena that is loyal to the Kremlin, from the federal level down to the local level. The system may not allow the opposition to take part in elections, it may guarantee victory for pro-Kremlin candidates, but it has no role in everyday management.

The key political actors right now are the regional governors, who have shown they’re not afraid to challenge the government, and who are making full use of their regional authority, which has unexpectedly proved most useful in a time of crisis. Years of reform have sharply reduced the regions’ financial independence, but Russia remains a federation, and the crisis has finally given the governors a chance to show the extent of their autonomy on issues that are not directly related to Putin.

The typical regional governor would never question the annexation of Crimea or call for the opposition to be allowed to run in elections, but is more than capable of ignoring ministers’ instructions regarding lockdown measures and introducing tougher measures as they see fit, including restrictions on traveling between regions. Every governor understands perfectly where their fate will be decided, and it’s not in the government.

The fact is that the government and public understand each other less and less, and have increasingly divergent priorities and values. This is happening at a time when the institutions that should regulate relations between the government and society are in no state to do so. The United Russia ruling party is paralyzed: its leaders have remained on the sidelines of the crisis.

Right now there is no obvious alternative to Putin, but as people find themselves in increasingly dire straits, any alternative will appear as a lifeline. For now, annoyance and unhappiness are building up, and much will depend on the extent and duration of the crisis. But for the government, a sociopolitical fallout is inevitable.

Demand in society for alternatives is growing, while the choice is only shrinking. The government minimizes the political role of even the most harmless candidates in elections, ensuring there is no risk to the Kremlin appointee. The idea of scrapping gubernatorial elections (again) is making a comeback. This is the simplest way for the authorities to safeguard themselves against the consequences of the current crisis and shore up administrative control.

Reducing the choice to a simple “for or against Putin” doesn’t allow the authorities to get a real sense of the public mood or to predict its behavior, and Putin’s rating does not reflect the real mood. Russia is rapidly approaching a situation in which the public will lose the right to decide anything once and for all, because the authorities simply have no remaining political will or the resources to persuade people.

The current perfect storm will end in the virus being defeated, but Russian society might find itself defeated alongside it. The state sees support for it as its dues, and protests as the result of manipulation. This will lead to more authoritarian administration: even more direct control over political processes, elections, and all forms of civil activity, causing social irritation to look for an outlet.

Contradictory trends are in store for Russia. On the one hand, the authorities are doomed to tighten the screws, yet the growing rivalry among the elites makes repression chaotic and indiscriminate. On the other hand, the number of local protests (mostly nonpolitical and small-town, for now) will grow. This will add to the growing unhappiness and assertiveness of party branches in the regions: a factor that will contribute to the erosion of the regime.

Putin was right when he said on March 12 that the right to run again in presidential elections was no guarantee of victory. As things stand in Russia today, the Kremlin cannot really guarantee anything, unless, of course, it decides to give up any pretense of democracy and follows the path taken by China.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Tatiana Stanovaya is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Signs of an Imminent End to the Ukraine War Are DeceptiveCommentary

- Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Finally in Sight?Commentary

Tatiana Stanovaya

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Russia’s Response to Its Spiraling COVID-19 Crisis Is Too Little, Too LateCommentary

As Russia weathers a fourth surge of COVID-19 cases, the country’s management of the public health challenge has yet to improve. What factors led the country here, and what does this mean for the Putin regime and the Russian people going forward?

Paul Stronski

- Civil Society and the Global Pandemic: Building Back Different?Paper

Civil society groups are simultaneously responding to the pandemic’s direct impacts and looking to a post-pandemic future. Many economic, political, and geostrategic challenges are shaping their thinking and their strategies.

Carnegie Civic Research Network

- Is There Any COVID-19 Vaccine Production in Africa?Commentary

Efforts are being made to ramp up production of COVID-19 vaccines in Africa to address the continent’s low rate of vaccination. As of September 2021, there are at least twelve COVID-19 production facilities set up or in the pipeline across six African countries.

Zainab Usman, Juliette Ovadia

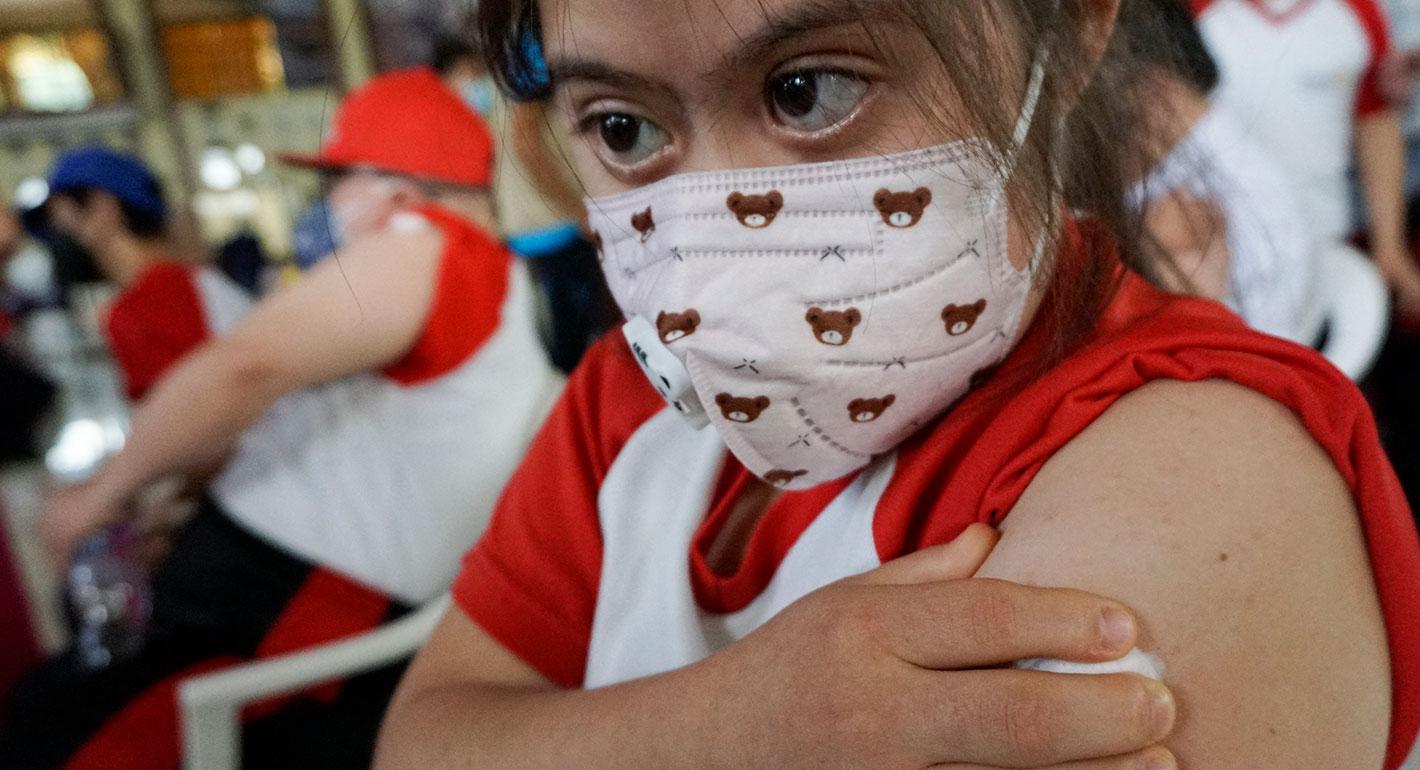

- How the Global Vaccine Divide Is Fueling Indonesia’s Coronavirus CatastropheCommentary

As Indonesia reels under staggering rates of COVID-19, an ambitious mass inoculation drive offers hope. But limited access to effective vaccines is trapping the Asian giant in an impossible choice between saving lives and livelihoods.

Sana Jaffrey

- Russia’s Vaccine Diplomacy Is Mostly Smoke and MirrorsCommentary

Russian scientists rolled out the country’s COVID-19 vaccine last summer, beating Western vaccine producers to the finish line. But scarce data, broken promises, and corruption have led the vaccine to lose its luster.

Grace Kier, Paul Stronski