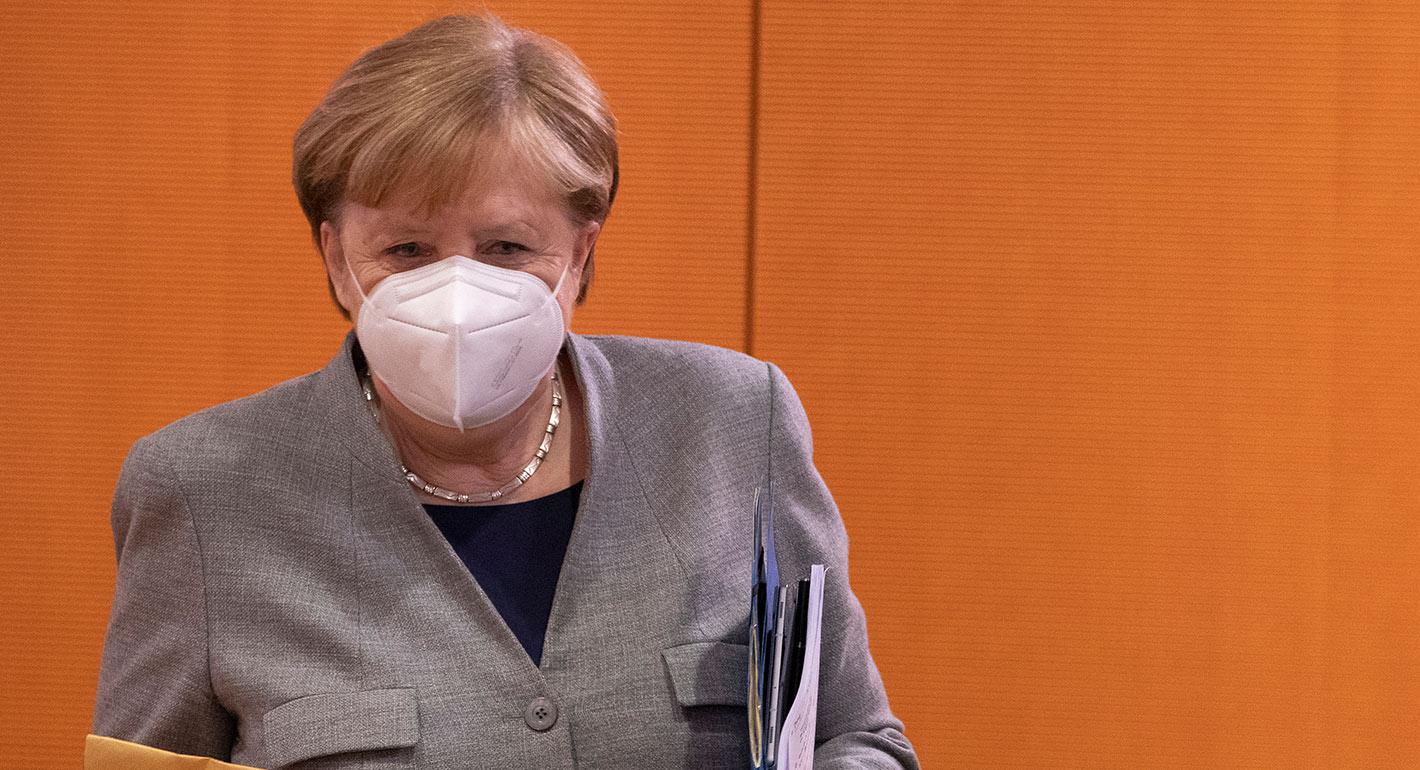

Unless the coronavirus pandemic upends Germany’s federal elections in September 2021, Chancellor Angela Merkel will be political history.

This consummate politician—chancellor since 2005—will leave the center stage after winning four elections for her Christian Democratic Union party (CDU).

But before she does so, Merkel has to deal with some urgent matters. She must ensure that Germany and the EU can economically recover from the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic that is sweeping across Europe.

She has a few months to mend bilateral and transatlantic relations with the incoming U.S. administration of Joe Biden.

And she must give the EU the direction and strategy it needs to deal with China and Russia at a time when both countries are sowing divisions in Europe and exacerbating tensions in the transatlantic relationship.

Merkel’s Would-Be Successor

Whoever succeeds Merkel has big shoes to fill. Armin Laschet, the fifty-nine-year-old son of a coal miner, is likely to run for chancellor after having become CDU’s new leader during a virtual party conference on January 16. He beat his main contender, Friedrich Merz, a longtime critic of Merkel and a politician turned businessman. Ahead of the vote, Laschet told delegates, “The Germany I imagine is a European Germany.”

Despite his avuncular manner, Laschet is no pushover. He is currently the premier of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s most populous state. This conservative centrist, against all the odds, won that top job in 2017 in a region long considered the bastion of left-wing Social Democrats.

Since then, Laschet has pursued Merkel’s centrist policies. He supported her decision to allow over 1 million refugees fleeing the war in Syria to enter Germany in 2015. He has spoken out against the far-right, anti-immigration party, the Alternative for Germany. He advocates for integration and inclusive policies. He is an intensely pro-European politician, having served as a member of the European Parliament. And like Merkel, he’s a consensus builder.

Over the past year, the pandemic tested his political and leadership skills. He was slow and indecisive about imposing a lockdown, even as the virus raced through his state. Since then, he has signed onto Merkel’s tough lockdown policies.

On climate change, he supports the coal industry lobby that is still strong in the region but also wants much more renewable energy sources. Indeed, if he wants to be the next chancellor, he needs a greener profile, particularly since current opinion polls show that the Greens are now the second-biggest political party. That makes them possible coalition partners for the Christian Democrats. Were that to happen, Merkel’s legacy might be challenged.

Merkel’s Legacy

Under Merkel’s helm, Germany changed. She moved the conservative, male-dominated Catholic CDU party to the center, which is no easy feat for someone brought up in communist East Germany and whose father was a Lutheran pastor.

She abolished military conscription, eventually came around to accepting single-sex marriage, gave parents more flexibility when it came to taking leave for newborn children, and supported the introduction of a minimum wage.

But her two biggest domestic decisions—closing nuclear power stations and throwing open Germany’s doors to over 1 million refugees—shook her party and showed her real grit.

The former decision broke the back of the powerful energy lobbies that had close ties with the CDU. The latter spurred the rise of the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany party. Over the past few years, the far-right party has attracted CDU supporters disgruntled with Merkel’s policies.

Yet that trend changed with the arrival of COVID-19. Merkel’s steady handling of the pandemic reassured voters. Her approval ratings soared to over 70 percent. Her standing confirmed how crisis management has always been her forte, whether saving the euro during the global financial crisis of 2009, keeping Europe together during the refugee crisis, or now coping with the pandemic.

Her legacy, however, is inconsistent, especially with regard to Russia and China and some of the EU’s own member states.

Merkel took a very hard line against the Kremlin when Russia illegally annexed Crimea in early 2014. She persuaded other EU leaders to impose sanctions on Russia and has repeatedly criticized the way in which Russian President Vladimir Putin has cracked down on human rights and opposition figures.

When a Russian opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, was poisoned last summer by operatives sent by the Kremlin, it was Merkel who brought him to Berlin where he was treated and protected around the clock. As soon as he returned to Moscow on January 17, Navalny was arrested. Merkel’s support for him shows her commitment to human rights and individual freedoms.

Yet her critics, especially the Green party, say the chemical attack on Navalny was the ideal opportunity for Merkel to either impose further sanctions on the Kremlin or stop the construction of Nord Stream 2. This second pipeline being built across the Baltic Sea will bring more gas directly from Russia to Germany. It will make Germany more dependent on Russian energy. It provides Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned energy giant, with lots of cash. And the project has often soured relations with Poland and Ukraine; both countries earn lucrative transit fees for transmitting Russian gas to Europe.

Despite her warnings to Putin over the Navalny case, Merkel chose not to stop Nord Stream 2 or apply new sanctions. This is a puzzle for her domestic supporters and allies.

The other puzzle is Merkel’s China policy.

The Trump administration has repeatedly applied pressure on most European governments to avoid using Chinese technology for the 5G telecommunications networks. It wasn’t just because of Trump’s anti-Chinese policies. There are serious security considerations, which Merkel’s own party and the intelligence services have repeatedly warned her about. Several European governments have decided to ban the Chinese technology. Merkel, on the other hand, insists there will be safeguards.

On another Chinese-related issue, Merkel introduced a much tighter screening policy for Chinese investments in Germany, recognizing the security concerns for companies and the need to protect German strategic assets. Yet just before Germany ended on December 31 its six-month stint in heading the European Council, Merkel pushed through an ambitious EU-China investment deal.

The deal was forged against the backdrop of Beijing’s fierce crackdown in Hong Kong, its imprisonment of individuals critical of China’s handling of COVID-19, the detention and re-education camps for the Uighur minority, and China’s increasingly authoritarian rule.

Merkel’s support for human rights and the rule of law doesn’t square with her policy toward China. Compared to the sharp criticism by the United States and the UK on China’s record on human rights both on the mainland and in Hong Kong, the response by Germany and the EU has been timid. She could have made a difference.

Even inside the EU, Merkel has refrained from sanctioning Poland and Hungary. The Polish government continues to systematically undermine the independence of the judiciary and the courts. The Hungarian government has clamped down on nongovernmental organizations, academic institutions, and a free media. Merkel’s critics, particularly the Greens, accuse her of not standing up for the EU’s values and principles.

Merkel’s supporters say she is a pragmatist at heart, one who over the years has kept the EU together during crises and who doesn’t want to burn bridges. That pragmatism has won her party four successive elections. But if Laschet manages a fifth term for the CDU and if the Greens become the CDU’s coalition partners, continuing Merkel’s legacy will not be a given. The Greens will push for a more assertive policy toward China and Russia and a more active role on defense and security issues inside NATO, an organization in which Merkel had little interest. They also will push for more European political and economic integration and an EU that will do much more to defend values inside and outside the bloc. The center—pursued by Merkel and supported by Laschet—may be in for a reassessment.