If the regime in Tehran survives, it could be obliged to hand Moscow significant political influence in exchange for supplies of weapons and humanitarian aid.

Nikita Smagin

{

"authors": [

"Konstantin Skorkin"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Russia",

"Eastern Europe",

"Ukraine"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

The Kremlin continues to view the breakaway republics as a buffer zone and Trojan horse inside a recalcitrant Ukraine, but allowing their inhabitants to take part in Russian domestic politics will help to score key propaganda points.

The more the Minsk agreements aimed at ending the conflict in eastern Ukraine dissolve into a diplomatic pipe dream, the more active Moscow is becoming in integrating the breakaway Donbas republics into Russian life. The September elections for the Russian Duma will be another—perhaps irreversible—step in that direction.

The upcoming Duma elections won’t be the first time that Moscow has involved the inhabitants of the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) and Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) in Russian domestic politics. The first attempt to make use of Donbas votes came during the nationwide vote on amending the Russian constitution last summer, when Russian passport holders who wanted to vote were bused into Russia’s neighboring Rostov region to do so. Back then, the number of voters was limited (by the coronavirus pandemic and the relatively small number of Russian passport holders there) to 14,500.

Now the number of people in the Donbas in possession of Russian passports has risen to 600,000, warranting a more serious approach to voting. There will be no polling booths on the territory of the LNR and DNR, to avoid incurring new Western sanctions. Instead, Russia’s newest citizens will be able to cast their votes remotely, via the internet.

Russia’s Central Election Commission ruled on July 21 this year that Donbas residents who hold a Russian passport and are not registered at a permanent place of residence in Russia would be allowed to vote online. With this in mind, the Rostov region was included in the regions permitted to trial electronic voting this time around.

As of the start of August, 148,000 people in the DNR (out of 300,000 Russian passport holders) had applied for a Russian Pension Fund ID number, required to gain access to the online voting system via the state services website. In the LNR, that figure was 158,000.

To simplify access to the Russian state services website, the DNR local network operator Phoenix is moving over to the international dialing code for Russia, +7, while the LNR operator Lugacom is already using Russian mobile number prefixes. Ahead of the vote, consultation points will open across both republics to provide assistance to anyone struggling to register to vote. And, of course, there will still be the traditional buses on hand, taking voters just over the border to polling stations in the Rostov region.

This flurry of activity doesn’t necessarily mean that Russia is preparing to officially invite the DNR and LNR to become parts of its federation. The Kremlin continues to view the breakaway republics as a buffer zone and Trojan horse inside a recalcitrant Ukraine, but their participation in Russian domestic politics will help to score key propaganda points.

Above all, allowing them to vote in the Duma elections will help Moscow to convince the inhabitants of the Donbas that it will not abandon them. And providing them with Russian passports and other official documents will enable them to integrate into Russia, on an individual basis at the very least.

The Kremlin is also interested in the people of the Donbas as additional reserves of loyal voters. After the worst fighting in 2014–2015, nearly everyone whose sympathies lay with Ukraine left the region. The rest may not feel any particular fondness for the LNR and DNR authorities and their semi-fictional statehood, but they are usually loyal to Russia. They are unlikely to support the opposition, and generally hold President Vladimir Putin’s policies and the current Russian authorities in high regard, so Russian parties are eager to court them.

The first party to make use of the Donbas issue was A Just Russia. After it merged with the writer Zakhar Prilepin’s left-wing nationalist For Truth project, the Donbas agenda became firmly established in the party’s manifesto, including demands for Russia to recognize the DNR and LNR. Prilepin himself fought in the Donbas conflict as a field commander, and is now trying to convert his image as an insurgent into votes by running for the Duma. Also representing A Just Russia-For Truth is Alexander Kazakov, a former advisor to the assassinated DNR leader Alexander Zakharchenko.

Russia’s Communist Party also has an interest in the Donbas voters. Again, its position is that Russia should immediately recognize the DNR and LNR. Traditionally, support for the Communists was strong in the Donbas: it used to be something of a “red belt” for Ukraine. But in recent times, Russian state media (which has the unreserved trust of many in the Donbas) has portrayed it as a protest party, which might work against it.

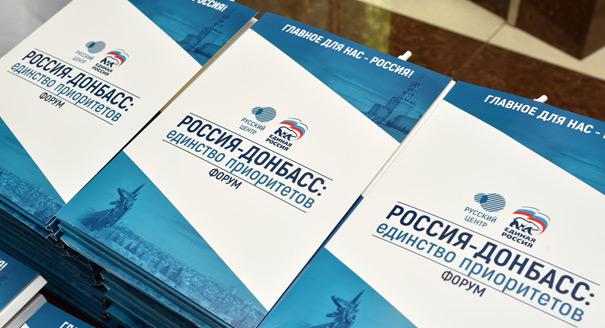

The domestic politics bloc within the Russian presidential administration couldn’t possibly leave such a propaganda gold mine to the opposition parties—even the “in-system” ones that the Kremlin allows to play a role—so the ruling United Russia party has also turned its attention to voters in the Donbas. In May, Andrei Turchak, secretary of the United Russia general council, visited Donetsk: the first official visit to the DNR by a party heavyweight. In addition, the United Russia party list for the Rostov region now includes the name of Alexander Borodai, one of the founders of the DNR and its former prime minister.

It’s likely that United Russia will receive the most votes in the Donbas. Inhabitants of the self-proclaimed republics are counting on the Russian authorities alone to resolve their fate, so voting for the ruling party is, for them, akin to investing in their own future: they hope their loyalty will not go unforgotten by Moscow.

The Ukrainian Foreign Ministry has already protested the decision by Russia’s Central Election Commission to allow people in the Donbas to vote electronically, but there is little Kyiv can actually do. Its calls for new sanctions against Russia and for the West not to recognize the Russian elections will most likely go unheeded. (Kyiv did not recognize the last Duma elections either, since voting took place in Crimea.)

Ukraine missed the window of opportunity when it would have been much easier to implement the Minsk agreements: when it would have been a question of reintegrating a region that was admittedly hostile, but one that was nevertheless close and understood. In the years that have passed since the conflict began in 2014, Donbas has drifted further and further away from Ukraine. Economic ties have been severed, the media landscape is completely controlled by Moscow, and the region is populated by more and more people with Russian citizenship.

It’s hard to imagine a situation in which Ukraine could reincorporate a region whose loyalty is entirely directed toward a neighboring country, and which has representatives in the parliament of another country. That means that Kyiv will only procrastinate even further over the implementation of the Minsk agreements, in the hope of some global changes in the future.

Moscow, for its part, has not given up on reintegrating the Donbas into Ukraine, giving it a way in to Ukrainian domestic politics, but essentially sees the DNR and LNR as a useful buffer zone on its western border. Even while insisting at an international level on the return of the Donbas to Ukraine, Moscow is binding the breakaway region to itself ever more closely. With every Russian passport handed out there, and every vote cast in Russian elections, the chances of resolving the Donbas crisis in the way envisaged through the Minsk 2 agreement gets slimmer and slimmer.

Konstantin Skorkin

An independent journalist.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

If the regime in Tehran survives, it could be obliged to hand Moscow significant political influence in exchange for supplies of weapons and humanitarian aid.

Nikita Smagin

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

The interventions in Iran and Venezuela are in keeping with Trump’s strategy of containing China, but also strengthen Russia’s position.

Mikhail Korostikov

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber