- +2

George Perkovich, Jessica Tuchman Mathews, Joseph Cirincione, …

REQUIRED IMAGE

10 Plus 10 Doesn’t Add Up

This week, the heads of the world’s leading market economies – the Group of 8 -- convene in Scotland for their annual summit. Important issues including debt relief and global warming will dominate the agenda.

This week, the heads of the world’s leading market economies – the Group of 8 -- convene in Scotland for their annual summit. Important issues including debt relief and global warming will dominate the agenda. Unfortunately, these items have displaced nonproliferation from the top of their action plan. The G-8’s ground breaking commitment, unveiled at the 2002 summit in Kananaskis Canada to spend at least $20 billion over 10 years to combat weapons of mass destruction – known as the Global Partnership or 10+ 10 over 10 -- has fallen short on its promise and the urgency of confronting the spread of unconventional weapons is fading in many G-8 capitals, including Washington. While several non-G-8 countries have signed onto the initiative in the past three years, the non-U.S. core partners have not yet reached their target of $10 billion in pledges and far less than that amount has actually been spent to date, despite critical proliferation risks in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere. It is time for the G-8 countries to recommit themselves to the nonproliferation cause and re-energize their collective efforts.

As the countries with the most to lose economically from the use of any unconventional weapons, but most of all from a nuclear weapon, the G-8 has a compelling self-interest in ensuring that nuclear weapons do not spread and are not used. Yet despite the worthy goals of the 2002 Global Partnership, demand for and availability of nuclear weapons and materials far outstrip programs to prevent their spread. In fact, less nuclear materials were secured in Russia in the two years after the 9/11 attacks than in the two years before the strikes. Several key U.S. nuclear security programs have timelines that stretch out over a decade, time few experts believe we can afford in the battle against proliferation. Many G-8 pledges remain nothing more than promises and those monies that have been spent have gone to important, but less critical projects, including attack submarine dismantlement, instead of efforts to secure nuclear weapons, or eliminate nuclear materials.

To reinvigorate efforts, the United States should push its G-8 partners on two fronts. First, the United States should convince all G-8 states to appoint single, permanent points of contact responsible for coordinating and accelerating their nonproliferation efforts. These officials should be assigned the G-8 nonproliferation agenda full time and the coordinators’ group should meet regularly to ensure the Global Partnership makes steady progress. Today, no single person within the U.S. or any other G-8 partner government has such a role, and as a result, many key efforts are mired in bureaucratic wrangling and secondary legal battles. President Bush should appoint a U.S. coordinator immediately, to get the ball rolling.

Second, the U.S. should work with its G-8 partners to make the global economic consequences of a terrorist nuclear strike clear to the entire world. Many less prominent countries still suffer from the illusion that the nuclear threat facing likely targets is not a real threat to them. Yet the 9/11 attacks made clear that the economic impact of terrorism is global and a nuclear strike would dwarf the airplane-based attacks on New York and Washington. Thus, the finance and intelligence ministers within the G-8 should develop an economic risk assessment to help define the likely economic consequences of a nuclear strike. Today, no such estimate exists. It is likely that the outcome of such a study would make the cost/benefit analysis of early and effective prevention even clearer than it is today. This initiative is separate from the equally important and overdue need for leading states to develop a traditional joint proliferation risk assessment that could help states set priorities for funding and projects, but an economic assessment could add much needed energy to broader nonproliferation efforts.

If the leading economic powers on earth cannot demonstrate the commitment and urgency the threat of nuclear terrorism and proliferation demand, then we have little hope of preventing those who seek to use nuclear capabilities against us from succeeding. But in making this choice, we have to remember that there are no good responses once a nuclear weapon, or enough nuclear material to produce one, goes missing. Prevention is all we have, and we must do better than we are doing today.

Jon Wolfsthal is the Deputy Director for Non-Proliferation at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC.

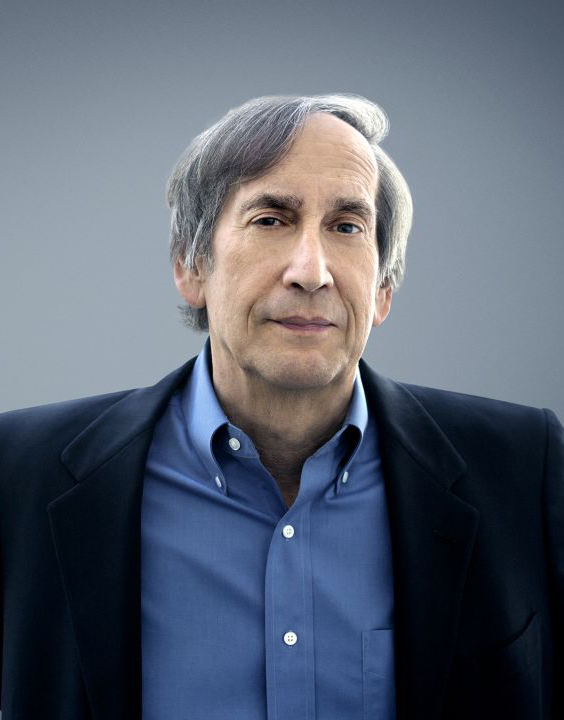

About the Author

Former Nonresident Scholar, Nuclear Policy Program

Jon Wolfsthal was a nonresident scholar with the Nuclear Policy Program.

- Universal Compliance: A Strategy for Nuclear Security<br>With 2007 Report Card on ProgressReport

- Talk Now, Talk Fast on North KoreaArticle

Jon Wolfsthal

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

The use of technology to mobilize Russians to vote—a system tied to the relative material well-being of the electorate, its high dependence on the state, and a far-reaching system of digital control—is breaking down.

Andrey Pertsev

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Promoting Responsible Nuclear Energy Conduct: An Agenda for International CooperationArticle

These principles aim to codify core responsible practices and establish a common universal platform of high-level guidelines necessary to build trust that a nuclear energy resurgence can deliver its intended benefits.

Ariel (Eli) Levite, Toby Dalton

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

Putin is stalling, waiting for a breakthrough on the front lines or a grand bargain in which Trump will give him something more than Ukraine in exchange for concessions on Ukraine. And if that doesn’t happen, the conflict could be expanded beyond Ukraine.

Alexander Baunov