Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

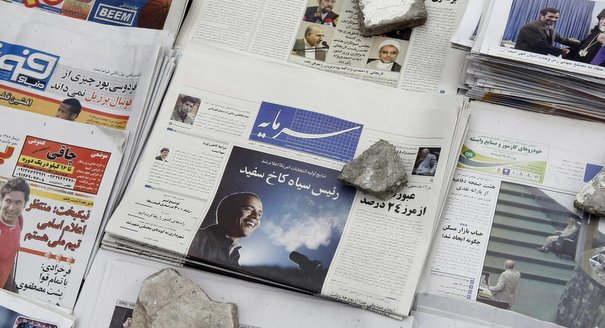

Source: Getty

President Obama's Video Message to Iran: Q&A with Karim Sadjadpour

President Obama reached out to the Iranian people and leadership on Friday in a recorded video message on the New Year holiday of Nowruz. Karim Sadjadpour discusses President Obama's Nowruz overture to Iranians, its likely reception, and next steps for U.S. policy makers.

President Obama reached out to the Iranian people and leadership on Friday in a recorded video message on the New Year holiday of Nowruz. In a new Q&A written from Dubai, Carnegie’s Karim Sadjadpour discusses the president’s overture, its likely reception among Iranians, and next steps for U.S. policy makers.

Why did President Obama choose this occasion for his video message to Iran?

It’s very thoughtful timing. In acknowledging Nowruz, President Obama showed the Iranian people that he has an appreciation for their culture and history. In Dubai, the reaction among the huge Iranian expat community has been overwhelmingly and universally positive.

Was there anything about the tone and language of Obama’s remarks that struck you as particularly significant or deliberate?

Obama made it clear to Tehran’s leadership that his administration is committed to diplomacy, and is genuinely interested in overcoming the tremendous mistrust that has developed over the last three decades. He mentioned the word “respect” several times, which is what Iran’s leaders always claim U.S. policy has lacked.

How would you rate Obama’s foreign policy toward Iran thus far?

It’s only been a couple months, but thus far I think the Obama administration’s approach to Iran has been more informed and nuanced than that of any U.S. administration in the last 30 years. Obama has been respectful without projecting weakness, which is always a difficult feat to achieve.

What can we expect Obama’s effort to accomplish?

Ultimately it takes two to tango, and at the moment, hardliners in Tehran who are not interested in having an amicable relationship with the United States have an inordinate amount of influence.

Rather than strengthen these hardliners, Obama’s overtures will put pressure on them to justify their often gratuitous enmity toward the United States. Most Iranians recognize that, in 2009, the “death to America” culture of 1979 is obsolete—it only prevents the country from fulfilling its enormous potential.

Whereas the Bush administration united Iran’s disparate political actors against a common external threat, the Obama administration, I believe, is going to deepen the divisions and incongruities among Iran’s political elites.

How should the Obama administration focus its efforts in Iran?

The administration should attempt to discern which Iranian policies are driven by immutable revolutionary ideology, and which are merely a reaction to punitive U.S. measures.

The United States should continue to focus on Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, whose authority is far greater than that of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. All of the most influential institutions in Iran—the Revolutionary Guards, the Guardian Council, the presidency, and the parliament—are led by individuals who were either appointed by Khamenei or remain unfailingly loyal to him.

Is the nuclear issue the biggest cause of tensions between the United States and Iran?

The nuclear issue is the trickiest of all, but it is only a symptom of greater mistrust between the United States and Iran, not the underlying cause of it. The United States must sustain an airtight multilateral approach on the issue, maintaining clear redlines and ensuring that the international community will respond if Iran crosses them.

Is there a consensus in Iran about re-establishing relations with the United States?

U.S. policy makers must recognize that certain Iranian elites, and others among the country’s allies in the region do not want to see a rapprochement between Iran and the United States, because that would diminish their influence and open them up to new kinds of competition. A small group of spoilers will likely attempt to subvert serious dialogues, perhaps by jailing Iranian-Americans on trumped-up charges, or sending new, large and conspicuous weapons shipments to Hamas or Hizbollah. But if the United States ends its confidence-building efforts in retaliation, it will strengthen the influence of hardliners seeking to derail an eventual reconciliation.

How should the Obama administration craft its rhetorical approach to Iran?

Hostile American rhetoric allows the Iranian leadership to portray the United States as an aggressor, and Obama’s remarks were very carefully crafted to play down that perception. But Obama should also be mindful of who he talks to, and when.

Notwithstanding private, introductory discussions, as well as ambassadorial-level meetings in Kabul and Baghdad, the United States should refrain from making any grand overtures to Tehran that could redeem Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s leadership style and increase his popularity ahead of the country’s June 2009 presidential elections. Since assuming office in August 2005, Ahmadinejad has used his influence to amplify objectionable Iranian foreign practices while curtailing domestic political and social freedoms and flagrantly disregarding human rights. His continued presence could serve as an insurmountable obstacle to confidence building with the United States.

Even if confidence building doesn’t succeed, the Obama administration’s diplomatic approach can help the Iranian people recognize that their own leadership is the impediment to improved relations, not the United States.

How will the Iranian regime respond internally to Obama’s overture?

With Obama having clearly expressed his support for reconciliation with Iran, this becomes an internal Iranian battle, and unfortunately, it won’t be resolved anytime soon. But Obama shows in this video that instead of tipping the scales in favor of the radicals, as the Bush administration did, he will pursue diplomacy to undermine their narrative that a hostile U.S. government is bent on oppressing Iran.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Karim Sadjadpour is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on Iran and U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East.

- What’s Keeping the Iranian Regime in Power—for NowQ&A

- How Washington and Tehran Are Assessing Their Next StepsQ&A

Aaron David Miller, David Petraeus, Karim Sadjadpour

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Firepower Against WillpowerCommentary

In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

- Georgia’s Fall From U.S. Favor Heralds South Caucasus RealignmentCommentary

With the White House only interested in economic dealmaking, Georgia finds itself eclipsed by what Armenia and Azerbaijan can offer.

Bashir Kitachaev

- Who Will Be Iran’s Next Supreme Leader?Commentary

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

- Turkey Has Two Key Interests in the Iran ConflictCommentary

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh