Political forces in Egypt today face a dilemma: either proceed ahead expeditiously to elections in order to end the post-revolutionary rule of the military or slow down the electoral timetable and prioritize the writing of a new constitution. New political parties want more time to organize; parties, movements associated with the January revolution, and civil society groups are also pushing for guarantees concerning the content of the new constitution and the process by which it will be written.

There is also reason for serious concern that Egyptian authorities cannot be prepared to administer parliamentary elections—with results that will be accepted as legitimate by Egyptians—as soon as September, particularly if the military leadership insists on using the extremely complicated electoral system outlined in a draft law proposed on May 29. Thirty-six different youth and political groups have joined the “Free Front for Peaceful Change” in backing a “Constitution First” campaign, which is seeking 15 million signatures to support a revised timetable. The coalition has

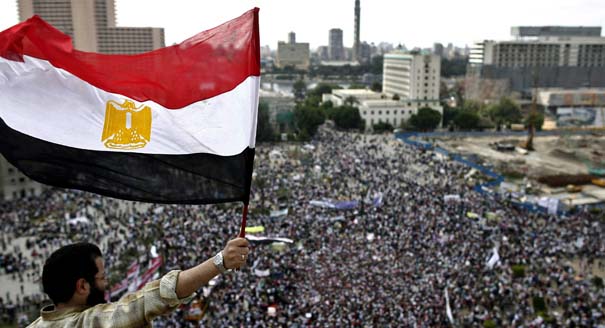

threatened to bring a million protestors into Tahrir Square on Friday, July 8 to protest, but the military leadership might still meet at least some of their demands before that.

Crosscutting Concerns

While the atmosphere in Cairo now is increasingly normal—economic productivity and tourism seem to be reviving, albeit slowly, while protests and new prosecutions of former officials and businessmen are declining—the struggle among political forces is heating up as the parliamentary elections planned for September approach. Political groups are expressing at least three sets of fears: that military rule will persist, that the National Democratic Party (NDP) will re-emerge in some form, and that the Muslim Brotherhood will dominate. These concerns pull activists in different directions, creating a confused political scene and conflicting sets of priorities.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) has made clear that it is eager to relinquish formal power to civilian authorities. Recently it articulated a desire, however, to retain significant political influence in the future. General Mamdouh Shahin suggested on June 16 that Egypt’s new constitution grant sweeping powers to the military, including the right to intervene in political affairs to protect the public interest and freedom from parliamentary oversight of its budget. A civil society conference with military participation on June 19 recommended that the new constitution make the military the protector of civilian institutions. Muhammad Saad Katatny, secretary general of the new Freedom and Justice Party established by the Muslim Brotherhood, points to the possibility that the military may be acquiring a new taste for power as the primary justification for holding parliamentary elections in September: “We must get the military back to the barracks; it is dangerous to let them continue in power too long.” Many businesspeople and others who once supported the Mubarak regime tend to share the desire for early elections, seeing a well-defined political timetable as critical to getting domestic and foreign investment flowing and the economy on its feet once again.

The Brotherhood and many other political forces share another concern, which is that the NDP might re-emerge in some form. While the top NDP figures—the Mubaraks, Secretary General Safwat Sharif, and Gamal Mubarak’s coterie of businessmen—are gone for good and the party itself was dissolved by court order in April, there is a widespread expectation that prominent families, particularly in rural areas, and businesspeople who formerly participated in the NDP will be able to leverage their old networks to win substantial parliamentary representation as independents or within parties. For this reason, the FJP, several of the other newly established parties—including liberals, leftists, and social democrats–and established political forces such as the Wafd and Ghad parties

announced on June 14 that they would field a joint slate of parliamentary candidates (the “National Coalition for Egypt”) in order to prevent an NDP resurgence.

But there are other coalitions forming as well that for the most part pit non-Islamist parties against the Brotherhood in a struggle over constitution first (or at least electoral delay) versus elections first. Constitution-firsters, mostly liberals and leftists, argue there is little sense in electing two houses of parliament and a president when the constitution to be written subsequently is likely to change the political system significantly enough to require all new elections within as little as a year. Behind their procedural argument is a fear that the FJP will do well in parliamentary elections and thereby have the largest say in shaping the constitution.

Election-firsters, led by the FJP, counter that a new constitution can only be legitimate if underpinned by elections; the current system mandates that the elected parliament choose a 100-member constituent assembly that would oversee the constitution’s writing, to be followed by a popular referendum on the document. They also argue that prioritizing constitution writing would violate the will of voters in the March 2011 referendum when three-quarters of voters supported constitutional amendments specifying the holding of parliamentary elections within six months.

Who will write the constitution and what will it say?

Egypt’s temporary constitution does not make clear who will write the document itself. Small committees combining judges, legal thinkers, and some politicians authored the constitutional amendments and new laws put out by the military leadership so far, and Deputy Prime Minister Yahya al-Gamal is reportedly working on a new draft constitution. The opacity of the process, as well as the fact that Muslim Brotherhood had a representative on the constitutional amendment committee while other political forces did not, has many political and civil society leaders worried.

Several political figures, movements, and civil society groups launched initiatives in early to mid-June aimed at preventing Islamists from dominating the process of writing and passing Egypt’s new constitution, no matter how many seats in parliament the FJP (which says it will nominate candidates for no more than 50 percent of the assembly) wins. Perhaps the most high-profile effort is one by presidential hopeful Mohammed ElBaradei who has

proposed a 17-article bill of rights that would exclude the military from the formal political process and guarantee citizens’ fundamental rights. Meanwhile, the Hisham Mubarak Law Center has launched an initiative under the slogan, “Let’s Write Our Constitution,” to promote citizen participation in drafting a constitution.

What the various initiatives have in common is an effort to secure assurances—from the SCAF, the Brotherhood, and in some fashion society at large—that the new constitution will enshrine universal human rights principles and what Egyptians refer to as “madniyyat ad-dawla,” that Egypt will be a “civil” state, not a religious one. Perhaps in order to secure Islamist cooperation on the latter, ElBaradei made what some observers have seen as a serious concession in his initiative, specifying that he would support the new constitution carrying forward language on Islam as the religion of the state and shari’a (Islamic law) as the main source of legislation.

The initiatives also seek to clarify the process for choosing the 100-member constituent assembly as this is not spelled out in detail in the temporary constitution. Muslim Brothers have been somewhat responsive to at least the latter concerns; Katatny said in a mid-June meeting that “a constitution cannot be imposed by a parliamentary majority but must take into account the views of all, including minorities,” and that “the constituent assembly must reflect the full diversity of Egyptian society.”

Muhammed Fayek, a former minister and veteran rights activist who now chairs a reformed National Commission on Human Rights, noted that the new constitution will be extremely important not only for the country but for the entire region due to the long history of Egyptian jurists writing other Arab constitutions and the likelihood that they will do so again in the future. “We export good things and bad,” he remarked.

Administering the Elections, Potentially a Major Problem

Few Egyptians have focused yet on what might be the most important argument for delaying parliamentary elections: Egyptian officials are unlikely to be ready to administer them in September. A proposed electoral law is still in draft form, adding to the uncertainty and inability of parties to mobilize effectively, and the specific dates for elections are still a matter of speculation. What is even more concerning is that the proposed system is nearly unparalleled internationally in its complexity. It envisages two-thirds of the assembly elected by individual districts and one-third through proportional representation (party lists). Several hundred seats are to be filled (the exact number remains unclear) and half of these must be reserved for workers or farmers, a carryover from the Nasserist era.

Moreover, Egypt has a unique system of electoral supervision by judges, but there are not enough judges to supervise each ballot box in the more than 50,000 polling places, necessitating the running of elections over several weeks in different parts of the country, with runoffs in each place. Despite this dizzying array of challenges and with only three months remaining before the elections, the electoral commission has not yet been called into existence. To complicate matters, the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, a time when little work is normally done, falls during August.

Factors are beginning to accumulate that suggest that the SCAF might relent and postpone elections. No electoral preparations are visible yet, most political forces other than the Islamists are pushing for at least a two- or three-month delay, and even the prime minister and several members of his cabinet have recently said publicly that they would prefer to see the constitution written first. While the revolutionary political forces were not strong and unified enough to persuade Egyptians to reject the March referendum that laid out the current timetable, they can probably still muster enough support to mount a major demonstration on July 8. That gives the SCAF a couple of weeks to decide. In any event, if real electoral preparations have not begun by then, Egypt risks holding elections that will be so plagued by administrative problems that a large number of candidates will not accept the results and the assembly will be unable to be seated—further tying the political process into knots.