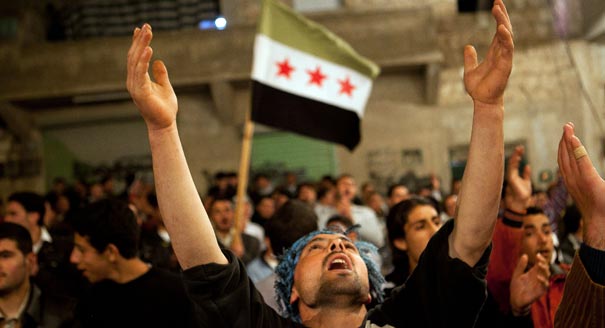

The endgame in Syria is approaching. The ongoing struggle between the opposition and the regime is reaching a climax. The suicide attack launched by opposition forces that killed senior members of the ruling elite was a ringing declaration of full-scale civil war against Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The opposition has made it clear that it will not accept any compromises and is willing to fight until it achieves victory.

What will Assad do? He is currently facing a deadlock. On the one hand, if he remains silent, it might be a sign of weakness and of a lack of confidence. If the Syrian president does not react harshly, even his staunchest supporters will turn away—with truly fatal consequences for his rule. On the other hand, if he retaliates with an iron fist, it will trigger more accusations that he is a cruel human rights violator and more.

There is a third option: Assad can admit defeat, withdraw from politics, and leave the country. But the probability that such a fallback option will actually be employed is low, even though it seems to be a good alternative.The crisis in Syria has reached a crescendo precisely when people are beginning to nourish hopes and expectations—in some cases unfounded, in some cases realistic—that a compromise, even if very flimsy, can be reached. Since key external actors, including the UN–Arab League envoy to Syria Kofi Annan, Russian President Vladimir Putin, U.S. President Barack Obama, and Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, are in constant contact, some believe there is still hope that the conflict will be resolved. Yet, at present, these talks make little difference.

It seems that the Friends of Syria group made up of external actors that support the opposition is incapable of controlling the Syrian rebels. But international proponents of the Syrian government are equally incapable of controlling Syrian regime supporters. It is not possible to make the belligerents negotiate.

For Russia, which supports Assad, the main difficulty is that it can neither rescue Assad nor compel him to be more balanced. Moscow will also be unable to prevent external military intervention. Russia is losing the last shreds of its influence in the Middle East, and it seems that after the already-inevitable fall of Assad, Moscow will have nothing left in the region. Indeed, this is one of the probable sources of Russia’s hopeless passion, with which it defends its last—inherited from the Soviet Union—Middle Eastern ally.

Other external parties to this conflict have their own difficulties, and with time, challenges will only mount. First of all, these states will have to be responsible for the opposition’s actions once it comes to power. The opposition’s record is by no means pristine, so further violence seems to be inevitable.

Second, the Friends of Syria group represents a wide spectrum of countries, so contradictions within the group are likely to arise. Qatar, for instance, has its own interests that diverge from those of Christian countries.

Thus external players have a difficult path ahead as well: they are all actors in and hostage to the Syrian tragedy.

.jpg)