A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

Source: Getty

Lebanon’s financial collapse and the Syrian conflict have allowed for the growth of an illicit economy, giving rise to a new breed of drug traffickers with ties to Lebanese parties and influence in the security forces. To address this, the country must adopt a comprehensive approach.

Syria’s conflict has given rise to Captagon traffickers in Lebanon, who wield greater political and institutional influence than traditional clan-based hashish traffickers. This is driven by several factors, including a growing cash economy in Lebanon, facilitating illicit trade, and a decline in rent from Gulf countries. Any effective response must account for economic realities in Lebanon and postwar Syria and be implemented swiftly to capitalize on the Assad regime’s downfall in Syria.

Over the past decade in Lebanon, one of the consequences of the conflict in neighboring Syria has been the expansion in the illegal production and trafficking of Captagon, a codrug of amphetamine and theophylline. The Captagon trade has introduced new, cross-sectarian actors who have leveraged political and security networks to accumulate immense profits and influence, surpassing Lebanon’s traditional tribal clan-based drug networks in reach and impact.

Since the first decade of independence after 1943, Lebanon’s drug trade had focused on hashish (or cannabis) production as well as opium production, and was concentrated along the eastern border with Syria in the northern Beqaa Valley. This became a matter of regional and international concern and foreign countries put pressure on the Lebanese authorities to address the problem.1 Lebanon often responded by dispatching the army and security forces to destroy hashish fields, while encouraging farmers to grow alternative crops. However, this failed to stem the drug trade. In reality, the authorities were playing a double game. On the one hand, they implicitly accepted a continuation of the drug trade, seeing it as compensation for the Beqaa’s marginalization. On the other, they tried to show foreign countries that they were responding to outside demands. Annual crop destruction became a ritual, albeit a largely empty one, whether before 1975, when the Lebanese civil war began, or after it ended—from the 1990s onward until roughly 2012, the second year of the conflict in Syria.

The main actors in the drug business hailed from major Beqaa clans. While these clans were often represented in parliament, their agricultural background and the fact that they operated within their clan’s areas limited their ability to impact politics in Beirut. The clans protected drug networks and allowed traffickers to hide from the authorities, while the drug trade provided jobs and allowed for limited development.2 For a weak Lebanese state, often navigating between national and regional crises, the Beqaa drug trade was usually a manageable nuisance.

However, in the past decade and a half since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, the Captagon trade introduced a new breed of drug traffickers from the Beqaa’s fringes which was not made up of members of major clans. These actors have cross-sectarian political affiliations, have accumulated larger profits—Captagon pills cost less than $1.00 to produce and can sell for as much as $20.00 in Gulf Arab markets3—and have developed an ability to influence politics and security in a more extensive fashion than clan-based traffickers.4 The careers of two Captagon kingpins, Mohammed Rashaq and Hassan Daqqou, both of whom were arrested, tried, and convicted by the Lebanese authorities, demonstrate the extent to which the trade can harm Lebanon’s state institutions and regional relations, particularly with Arab Gulf states, the main market for Captagon.5 The traffickers’ ability to extend their influence beyond sectarian and clan politics and develop relationships at the center of political life, while also recruiting members of the security services in their operations, underlines the threat they pose to the state’s stability and integrity at a time of domestic financial crisis and external economic pressures.

The traffickers have also benefited from other developments in Syria and Lebanon. These include U.S. sanctions on Syria, through the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act,6 or the sanctions the U.S. authorities have imposed in recent years on individuals, businessmen, and institutions in Lebanon.7 This is not to mention the collapse of the Lebanese financial system in 2019, which allowed bankrupt banks to deny or limit customers’ access to their bank accounts, a major consequence of which has been the growth of a cash economy.8 Whereas in the past, Lebanon’s political class lived off rents primarily from the Gulf states, this has largely dissipated as these states have focused their attentions elsewhere.

The growth of an illicit economy in Lebanon has provided an alternative source of funds, in what for now remains a poorly regulated environment. This makes it more difficult to curb the Captagon trade, while the sway of drug trafficking networks may allow them to impose new institutional and political realities in Lebanon and post-Assad Syria. Moreover, such networks, as they accumulate capital and political connections, can act as spoilers in any economic recovery or political transition. The Syrian regime’s downfall in December 2024 will present a short-term challenge for trafficking networks, as it was a main producer of the drug. However, given the existing production capabilities on the Lebanese side of the border and continuing demand in the Gulf states, Lebanon could see increased manufacturing of the drug in the future. That is why regional states and Western countries should seek to preemptively address this danger.

While the clan-based and Captagon drug networks may differ, the relationship between them is mostly symbiotic,9 and most of those cells of Captagon traffickers arrested by the authorities have also included clan members. The Captagon networks make use of the well-established, clan-based networks. Since Lebanon’s independence in 1943, clans in the northern Beqaa Valley, mostly Shiite but also Christian and Sunni, have been involved in growing, producing, and trafficking hashish and opium for sale nationally, while acting through intermediaries to sell their drugs regionally and internationally.10 Unlike Captagon, hashish and opium production is an agricultural endeavor, with a long chain of beneficiaries starting with peasants. The political affiliations of the clan-based traffickers and the violence they deployed often impacted their ties with other clans, while political parties and politicians in the Beqaa have sought to mediate in disputes and manage conflict, a role that Hezbollah has mostly taken on in more recent times.11

Clans offer protection to their members against government raids in a relatively remote region referred to as the jurd and characterized by a rugged mountain range. Drug traffickers often rely on networks from other Beqaa regions, notably the West Beqaa, to act as intermediaries in sales to foreign markets, particularly Latin America, where these networks have contacts.12 This has tightened profit margins and limited the impact of clan-based networks on politics and local development.13 Unlike profits from Captagon trafficking, those from the hashish trade are more spread out, which doesn’t allow for the accumulation of sufficient capital to gain wider political influence. Moreover, clan politics are rigid and clan relations and political connections are largely predetermined. The fact that the clans often engage in blood feuds has given politicians or parties major roles to play in reconciling them, which has limited the clans’ political power. Major drug traffickers have had to abide by clan politics, which since the 1990s have been dominated by allegiance to Hezbollah and its politics of resistance. Hezbollah and a second Shiite party, the Amal Movement, monopolize Shiite politics and have blocked the rise of alternative communal representatives, specifically in the Beqaa Valley.14

The leadership of Hezbollah and Amal originates mainly from southern Lebanon, which has further marginalized the underdeveloped Beqaa both in terms of Shiite and national representation. In the northern Beqaa, Hezbollah has focused not on the region’s development, but on responding to demands from the larger clans that the party address the fate of members jailed on drug charges.15 In the past, the government cracked down on drug production by destroying hashish fields before the harvest or arresting those involved in trafficking, while Hezbollah turned a blind eye.

This policy remained in place until 2012, when public calls to legalize hashish gained political support. Senior politicians, whether the then interior minister Marwan Sharbel, a Maronite Christian, or Walid Jumblatt, the Druze leader, supported legalizing hashish,16 citing the potential advantages of securing revenues for the strained national economy, especially after two U.S. states legalized marijuana.17 During this period, hashish traffickers from known clans, notably Nouh Zeaiter, made television appearances and contributed to the debate, calling for legalization. The absence of political will to curb hashish trafficking as well as Lebanon’s economic stagnation and the negative economic impact of the Syrian war were factored into these discussions, with the political class showing flexibility toward the networks.18

In tandem with this approach, Hezbollah, Amal, and their allies, acting on behalf of their clan constituents, backed an amnesty for the hundreds of people jailed on drug-related charges up until 2020, most of whom were from northern Beqaa clans.19 The amnesty did not see the light of the day, as it was caught up in demands by other Lebanese religious communities to see their members released from prison on various charges. Given the contentiousness of the amnesty issue, it was delayed indefinitely until a sectarian consensus could be reached. Nevertheless, an amnesty remains a serious option and would include Captagon traffickers. Hezbollah in particular sees this as an opportunity to bolster its support in the Beqaa, not least in light of the major damage caused to Shiite areas by the conflict with Israel in 2023–2024.

Links between Lebanon’s political class and clans engaged in drug trafficking have long been assumed, but are not a matter of public knowledge. They also do not indicate that the clans have used their connections to advance their drug interests. For example, one figure from the Beqaa, Yahya Shamas, both a politician and a suspected drug trafficker, was elected to parliament in 1992. In November 1995, he was arrested and charged with drug-related offenses, for which he served time in prison.20 Shamas denied the charges and said his confession was obtained under torture. He was assumed to be a drug lord during the 1980s and early 1990s.21 After his release, Shamas remained politically active within his clan and region. He ran in the elections of 2018, though he did not win.22 However, there were no signs he had exploited his parliamentary position to secure wider influence or improve cross-border relations for business purposes. In fact, his political ascendancy in the 1990s was seen as a reward for his financial success and connections with both Hezbollah and Amal, as well as with Syria’s effective viceroy in Lebanon at the time, General Ghazi Kanaan.23 Shamas’ political position served his clan but apparently not its business interests.

This replicated the example of another prominent trafficker-politician, Nayef al-Masri, who served in parliament during the 1970s. In 1970, the Greek authorities seized an airplane in Crete loaded with hashish, which reportedly had taken off from an airstrip on one of Nayef’s properties in the Beqaa.24 Lebanon’s interior minister at the time, Kamal Jumblatt, had accused Nayef of smuggling weapons, hashish, and cigarettes on his private jet.25 Yet, despite his ability to do so, Masri’s resources and reach remained largely confined to his region.

The most well-known clan figures in the drug business include Nouh and Mounzer Zeaiter and clan members from the Shamas and Masri families.26 While Nouh Zeaiter, the country’s most visible drug dealer, has been widely accused of trafficking in Captagon, he has denied these charges while admitting that he traffics in hashish.27 Yet members of the Zeaiter clan have been arrested in operations against Captagon networks. Nouh Zeaiter’s political connections are mostly restricted to the two dominant Shiite parties, Hezbollah and Amal. These connections have involved explicit demonstrations of support on his part, particularly during the conflict in Syria, when Zeaiter appeared at Hezbollah military positions, openly endorsing the party and then Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.28 Yet, beyond the Shiite parties, there are few signs Zeaiter has connections and influence over Lebanon’s political life or security services. He remains a wanted man, although the government has not seriously attempted to arrest him due to his ties with Hezbollah and he continues to appear regularly in media outlets.

The Captagon networks in Lebanon transcend borders in a way the clan-based networks do not. Unlike the Beqaa clans, the leading Captagon traffickers tend to come from smaller families and marginal border towns, and have strong connections on both sides of the border with Syria. Some are dual Lebanese and Syria nationals. They have also cut across political fault lines and fostered parallel interests among a wider array of actors than the clan-based traffickers, building connections in Lebanon and Syria as well as with transnational traffickers. The traffickers appear to have little interest in engaging directly in political life by securing political positions in state institutions for themselves, nor do they appear in media outlets. At the same time, however, their ability to find collaborators in Lebanon’s leading parties, such as Hezbollah, and in the security forces is a new and more worrisome characteristic of their behavior when compared to the clan-based drug traffickers.

Captagon networks are fairly ecumenical in that they do not restrict participation by members of clans and employ both Lebanese and Syrians. Investigations of the traffickers Rashaq and Daqqou showed that they employed clan members, though not from a single clan as in the case of the hashish or opium networks.29 There are advantages in hiring clan members, in that this extends the influence of Captagon networks to other regions while remaining independent of the clans’ political allegiances. It also provides flexibility in that clan members who are arrested are likely to be included in any eventual amnesty in the Lebanese multisectarian system, which tends to encompass prisoners from all religious communities. Such flexibility has allowed traffickers to maintain relations with a wide array of political or social forces, often antagonistic ones, keeping their networks’ options open. In Rashaq’s case, he had a residence in the mainly Christian area of Adma, near Jounieh, where the Lebanese Forces Party (a major opponent of Hezbollah) has influence and where Lebanese security forces are stationed.30 This demonstrated his comfort with navigating the complex Lebanese sectarian system. It is hard to imagine a trafficker from a Beqaa clan behaving in a similar way.

Judges, lawyers, and local officials confirm that in the last decade there has been a shift in the drug business from clan-based production and trafficking of hashish and opium to the production of Captagon.31 The Captagon trade requires greater trafficking expertise and a wider set of relations, and gathered pace during the Syrian conflict. It leveraged the established hashish and opium trafficking routes and networks in border regions, then relied on their political, security, and transnational connections to complete the cycle. In the Daqqou case, for instance, the accounts of his interrogations showcased his involvement in international shipments and in setting up front companies.32 Although the trade made Rashaq and Daqqou wealthy, their relations with the region’s clans did not spill over into violence, which would have been bad for the Captagon trade, given the clans’ military power and ability to mobilize.

The lack of violence between the two parties could be attributed to two factors. The first was the Lebanese government’s decision in 2012 to halt its annual destruction of hashish and opium fields, which helped sustain enough business for everyone. The decision was justified mainly as a measure to mitigate the negative economic impact of the Syrian conflict on Lebanon’s economically vulnerable border region. The second was the inclusion of clan members in the Captagon network and the overlap between different parts of the business—manufacturing, trafficking, and local distribution.33 From the information provided during the arrest of trafficking cells, each part of the business includes representatives from the different networks involved in the trafficking. They maintain and manage relations with clans in the border peripheries, which is as necessary as having political connections.

Among those involved in these networks are Hezbollah-affiliated individuals.34 In two cases, individuals connected with the party, including the brother of former parliamentarian Hussein Moussawi, were arrested for their role in manufacturing Captagon, while institutions such as Hezbollah’s Beqaa-based religious seminaries were said to hold stocks of the drug.35 Later investigations cited the party as a facilitator in the movement of drugs to the border region and southern Syria. Such evidence, while not as conclusive as in the case of the Syrian regime, was enough to link Hezbollah to the Captagon trade in public debates over the drug.36

The information surrounding the two Captagon traffickers arrested, Rashaq and Daqqou, reveals how the new class of traffickers is more sophisticated in the way it runs its operations than clan-based traffickers, whether in the capital it can raise or in its political and security connections.37 The 62-year-old Rashaq is from the Syrian town of Flita, near the border with Lebanon.38 The inhabitants of Flita, like those of many towns along the Lebanese-Syrian border, have maintained relations with the Lebanese side, specifically with distant relatives among the large families of Arsal, a mainly Sunni border town in the northeastern Beqaa. The absence of strict controls over the border since independence and the mountainous terrain around Flita have turned it into a smuggling hub where connections and cross-border relations have long been celebrated. Rashaq’s notoriety stemmed from his ability to operate from Arsal, which was a center for Syrian opposition groups, specifically the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra, today known as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which publicly split from al-Qaeda in 2017.39 In 2013, members of the town’s large Hujairi clan were injured in defending Rashaq against a kidnapping attempt. This highlighted his importance, though he was a Syrian trafficker in a Lebanese town.40 Simultaneously, Rashaq was also known for his ties with Hezbollah, which supplied him with ingredients for manufacturing Captagon.41 His ability to manage paradoxical relationships was not uncommon during this phase of the war in neighboring Syria, given the level of violence and lack of security on the Lebanese side of the border area.

Hassan Daqqou, who was born in 1978, comes from a poorer background. He also originates from a town on the Syrian-Lebanese border, Tufail, where smuggling is a major economic activity for many people, including Daqqou’s father.42 While Tufail is in Lebanon, it was more connected to the Syrian side of the border and has historically been disregarded given its location. Daqqou began selling watches in the street, but gradually expanded his activities to include a string of businesses that included owning a pesticide factory in Jordan, a car dealership in Syria, and a fleet of tanker trucks.43 His growing wealth allowed him to purchase a vast number of properties in Beirut and the Beqaa Valley. In his interrogation and trial, Daqqou spoke of his links with the elite 4th Armored Division of the Syrian Army, which was led by Bashar al-Assad’s brother Maher, as well as the assistance he provided to Hezbollah during the Syrian conflict.44 He also mentioned the role he had played in assisting the intelligence service of Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces, known as the Information Branch.45

The activities of Captagon traffickers, like those of the more traditional networks, have emerged from a specific socioeconomic context in Lebanon that has facilitated the rise of illicit activities, drug-related or otherwise. The Captagon networks have stepped into a vacuum created by the Syrian conflict and Lebanon’s financial and economic collapse in 2019–2020, as well as the structural shift that has taken the country away from a reliance on already declining regional rentierism.

Most alarmingly, the Captagon trade has permeated into the politics and security institutions of the Lebanese state. While there is no evidence that prominent individual members of the political class have been involved in trafficking, some appear to have developed ambiguous ties with traffickers, provoking uncomfortable questions in Lebanese society.46 Moreover, leading political parties, notably Hezbollah, are suspected of involvement in the drug trade. All this indicates that the Captagon trade may be far more difficult to eradicate than is believed.

The Syrian conflict was a major driver behind the expansion of the Captagon trade after 2012. The Assad regime faced great pressures because of the conflict due to sanctions and its refusal to accept any political solution that would have helped normalize the situation in the country. Starved of funds and unable to secure reconstruction financing, the regime integrated the Syrian military into the Captagon trade.47 This network of relations created surprising parallel interests as it also included cross-border smuggling networks that had been aligned with the Syrian opposition, as well as networks that benefited from Hezbollah’s cooperation or protection in Lebanon.48 Crucially, the Assad regime capitalized on the growing demand for Captagon in the Gulf states. Billions of dollars flowed into Syria from the Gulf, without political conditions, allowing Assad to wield the drug trade as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the affected Arab countries.49

Although the Captagon trade was initially a state-driven expansion under a precarious Assad regime in Syria, its foundations—sustained demand in the Gulf, technical expertise in producing Captagon, and vigorous transportation networks—extended beyond the regime itself. The spread of illicit economic activity such as Captagon trafficking reflected a dysfunctional response in Lebanon and Syria to the weakening of the rentier systems on which they had depended, where revenues from oil- and gas-producing countries had been redistributed through various means to non-oil producing countries, or limited oil producers. The two benefited from this rent, but its decline, due to sanctions on Iran and a shift in Saudi policies, along with the failing Lebanese and Syrian economies and political orders, forced both countries to turn to shadow markets to survive.50

Following the Assad regime’s downfall, much light was shed on its involvement in the Captagon trade.51 The regime had assumed a major role in mass producing the drug, with annual revenues estimated at some $10 billion in the period 2018–2019 and up until the downfall of Bashar al-Assad.52 This was a figure higher than Syria’s then GDP.53 The details of how the Captagon business grew to this scale has yet to be fully elucidated, though the trade had thrived between Eastern Europe and the Middle East during the 1980s, and was then brought to Syria by Bulgarian-trained chemists.54 Evidence from the Captagon networks pointed to a connection with Maher al-Assad’s 4th Armored Division and to fifteen major production facilities.55 Investigations by the Lebanese authorities established links between Daqqou and Maher al-Assad’s bureau chief, General Ghassan Bilal, who maintained regular contact with the network to discuss the delivery of Captagon consignments from Syria.56 Bilal was called “the boss” in Daqqou’s conversations. However, the subject matter between the two was restricted to Bilal’s end of the operation and did not cover Daqqou’s Lebanon activities, in which he communicated with various actors and facilitated shipments abroad. For instance, in Daqqou’s investigation files, leaked to media outlets, there are references to his Saudi SIM cards and contacts.57 For the border-based traffickers, Syria was a major but not the sole production hub. Daqqou had Lebanese connections, whether with Hezbollah or within the Lebanese state and market, and maintained relations with traffickers in countries to which Captagon was sent. While the Syrian regime was in solid control of its territories, its trafficking networks relied on the services and connections of people like Daqqou and Rashaq, who were therefore not easily replaceable.

Lebanon’s side of the Captagon trade, as revealed by the Daqqou investigation, pointed to a replication of the way the postwar political elite runs Lebanon—namely through a division of the national spoils among the main confessional leaders (referred to in Arabic as al-mohasasa).58 In other words, the country’s divisions notwithstanding, when it comes to crime, the networks have parallel interests. A number of factors came together to expand the scope of illicit activities. By the time of Daqqou’s arrest in 2021, the country had been two years into a financial and economic collapse. The regional funding of Lebanon’s political class had decreased with the change in Saudi leadership from 2015 onwards.59 The first Donald Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign against Iran impacted both Tehran’s own finances and Lebanon’s economy, with increasing scrutiny of the banking sector60. Hezbollah’s role in supporting the Assad regime and its presence along the Lebanese-Syrian border made it a de facto partner in Captagon trafficking. Washington accused Hezbollah of using the drug to finance its activities and imposed sanctions on affiliated individuals.61

The emergence of a cash economy in Lebanon thanks to the banking restrictions after the financial collapse of 2019–2020 played a major role in facilitating illicit transactions. In 2022, the cash economy was estimated at $9.9 billion, equivalent to just under half of Lebanon’s GDP, according to the World Bank.62 This developed alongside the widespread smuggling that was taking place across the Lebanese and Syrian borders, of gasoline and fuel oil in particular, with smugglers benefiting from the fact that Lebanon subsidized their price.63 Even when this costly system provoked severe shortages of essential commodities in Lebanon, the government sustained it amid accusations of collusion between politicians and smugglers.64 A highlight of this era occurred in the northern village of Al-Talil, where thirty people were killed by a fire in a warehouse where fuel had been stored.65 Those involved in fuel smuggling used their political connections to avoid accountability and paid families of victims to drop their lawsuits.66 Such connections and collusion, including with Hezbollah, were essential for conducting smuggling operations between Lebanon to Syria during the 2019–2022 period.

But smuggling was only the most visible side of the emerging illicit economy. Less so was the Captagon trade, even if, following Daqqou’s arrest in 2021, his photos with Lebanese politicians exposed disturbing associations. These photographs were widely circulated and showed the trafficker with former prime minister Saad Hariri, the secretary general of the Future Movement, Ahmad Hariri, and Hezbollah parliamentarian Ibrahim Moussawi. Daqqou’s contacts with Moussawi and with Saad Hariri, who was a leading anti-Assad figure who had supported the Syrian opposition during the early years of the uprising in Syria, showed his pragmatism.67 Daqqou’s transactions included buying cars from the country’s former interior minister Nouhad Machnouk, another anti-Assad figure, and receiving a license from the then interior minister Mohammed Fahmi to build storage facilities in his town.68 All the political figures denied that they knew Daqqou was a Captagon trafficker, although this is hard to believe. Daqqou’s convoy, lavish lifestyle, and border activity surely must have raised suspicions about the sources of his income among those otherwise wily politicians.69

An ability to span political divides, which Daqqou displayed, was also visible among traffickers in Syria, the Lebanese Captagon networks’ passage to the broader Middle East. While the Assad regime remained the main actor in producing the drug on an industrial level, the smuggling of Captagon into Jordan entailed dealing with established local networks. Some of these had been set up by commanders of Syrian opposition groups who had stopped fighting the regime after Russian-led reconciliation agreements in 2018, but nonetheless remained hostile to it.70 These commanders and networks were essential, as they knew the terrain, had links with Jordanian clans on the other side of the border, and could navigate a heavily militarized region. Given that Deraa Governorate in southern Syria remained insecure for government soldiers and violence persisted up until the regime’s collapse in December 2024, it is clear that local smuggling networks had agency with regard to the Captagon suppliers, and that the relationship was a marriage of convenience, given both sides’ need for resources.71 Opposition forces in Deraa would later mobilize and play a key role in toppling the regime.72

Also involved in the cross-border Captagon trade from Syria through Jordan was Merhi al-Ramthan, a local shepherd turned trafficker who was known as “Southern Syria’s Escobar.”73 In May 2023, the Jordanian authorities assassinated him in an airstrike.74 Media reports suggested that Ramthan had connections with the Syrian military intelligence services and Hezbollah,75 yet his strength stemmed from his ability to operate across the border. Given Jordan’s heavy securitization of the border, traffickers employed creative means of sending consignments across, including using swarms of drones and pigeons, while relying on difficult weather conditions to evade surveillance. The Jordanians also conducted airstrikes against two suspected drug traffickers in Syria’s Suwaida Governorate in January 2024.76

In northern Syria, the Captagon smuggling route to Türkiye also entailed collaboration between the Syrian regime and militant groups that are part of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA).77 The extent of SNA-affiliated involvement in drug trafficking is now public knowledge, with discussions of the matter in anti-Assad media outlets.78 The SNA’s presence in Syria has geographically expanded since the regime’s downfall.79

The Captagon traffickers’ connections also extended to the Lebanese security forces, as well as to senior figures on the demand side in the Gulf states. Mohammed Rashaq’s links to security officers made headlines,80 showing that he had recruited them to help conceal his activities.81 Indeed, one officer worked for him for years, and was later arrested. No less noticeable was Rashaq’s ability to secure his own release from a Syrian prison in 2011, underscoring his connections in Syria.82 His cross-border contacts famously included a Saudi prince, Abdel Mohsen bin Walid bin Abdul-Aziz, who was arrested in Beirut in 2015.83 The Saudi national, whom the Lebanese called the “Captagon Prince,” was arrested in November 2015 while preparing to leave with nearly 2 tons of Captagon in a private jet.84 The prince’s case demonstrated the prominence of the demand factor in Saudi Arabia, where sixteen government employees were arrested in October 2024 in a crackdown on the drug network.85

The Rashaq and Abdul Aziz arrests occurred as tensions rose between Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Hezbollah over the latter’s intervention in Syria and Yemen, and as Saudi Arabia was transitioning to the effective rule of Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In 2016, Rashaq was arrested along with a Lebanese Internal Security Forces (ISF) colonel who was referred to in media reports as “a partner” of the drug trafficker. While the arrests of Rashaq and the Saudi prince were linked, given that both were involved in Captagon trafficking, the way they were arrested, and by whom, suggested there were different political agendas behind each of the moves. Two different security agencies arrested Rashaq and Abdul-Aziz. Airport security, whose head at the time was affiliated with Hezbollah, arrested the Saudi prince. Rashaq, in turn, was arrested by the ISF’s Information Branch, which was loyal to former prime minister Saad al-Hariri, a Saudi ally, after it received intelligence on his activities from the authorities in the Gulf states.86 All this showed that the dynamics of the drug trade are often very much tied to politics, reflecting how Captagon trafficking has been integrated into broader political rivalries. This underscores, again, how difficult it may be to put an end to it.

While Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing arrangement virtually invites political influence over the security agencies, the Captagon networks’ diverse ties allowed them to ease the conditions of those detained, though this negatively impacted the country’s reputation and the integrity of its security services. For instance, the head of Lebanon’s custom authorities, who was affiliated with Hezbollah’s then Christian allies, the Free Patriotic Movement, was accused and arrested for illegally lifting the travel ban on Abdul-Aziz in 2020, months after the Beirut blast on August 4, which led to Saudi assistance for, and solidarity with, the Lebanese.87 The prince’s favorable treatment in Lebanon’s prison system was already under the spotlight after he had published a video of himself celebrating his birthday with friends.88

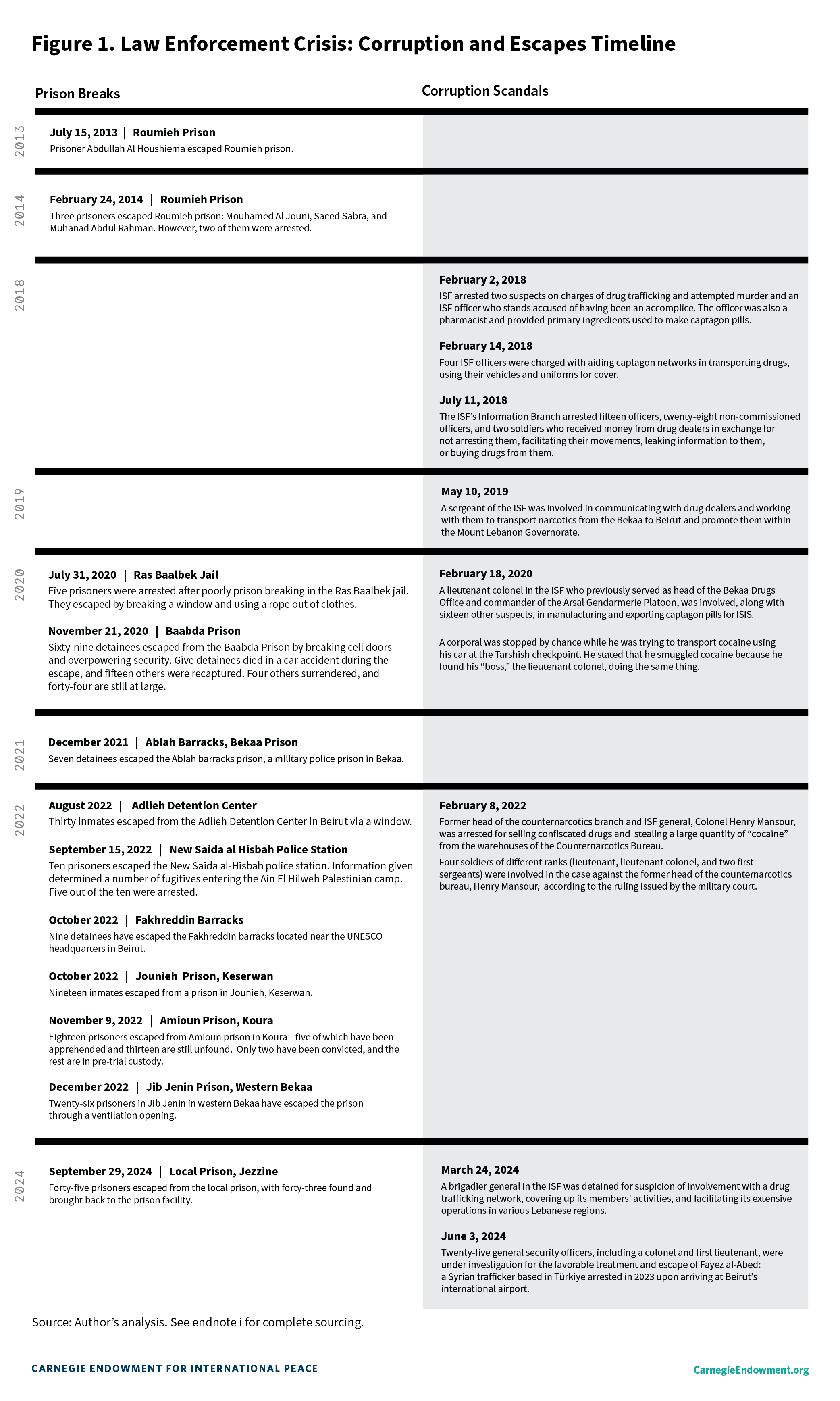

Such examples of indulgent treatment of those arrested for drug offences were a recurrent theme, specifically after the financial and economic crisis of 2019–2020. This was largely due to the depreciation of the Lebanese currency, and therefore a decline in the purchasing power of officers and soldiers. In 2018, four officers from the ISF were charged with aiding Captagon networks in transporting drugs, using their vehicles and uniforms.89 The post-2019 investigations into the drug trafficking connections of ISF personnel were much wider. A noteworthy case was the arrest in early 2022 of a former head of the counternarcotics branch, an ISF general, for selling confiscated drugs.90 The most recent case involved the investigation of twenty-five General Security officers over the favorable treatment and escape of Fayez al-Abed, a Syrian trafficker based in Türkiye, who was arrested in 2023 upon arriving at Beirut’s international airport.91 These cases demonstrate how traffickers have used their political connections and financial capabilities to bribe security officers and subvert their agencies (see figure 1).92

The Captagon networks’ connections across the political spectrum highlighted how the generalized corruption in Lebanon could benefit criminals. In this regard, they replicated the high-profile case of Bank Al-Madina in 2003. The bank was accused of money laundering, embezzlement, and fraud, and was eventually closed down by the country’s central bank.93 The main culprit, Rana Koleilat, was arrested, but was able to use her political connections and financial resources to turn her jail cell into what the media called “a serviced suite,” before escaping the country.94 The scandal exposed payoffs to politicians and security figures, and no doubt this was a factor in ensuring that Koleilat evaded accountability. The Bank Al-Madina scandal deepened public distrust in political elites, the security services, and the judiciary, and it is in precisely such an environment that the Captagon networks were able to prosper.95

This sociopolitical reality was also reflected in another dimension of the Captagon traffickers’ ability to penetrate the Lebanese political system, namely their suspected collaboration with Hezbollah. As the Trump administration sanctioned Iran from 2018 onwards, a trail of evidence pointed to the party’s connections to illicit networks, and specifically to the Captagon trade. Two trends were noticeable in Hezbollah’s approach to the Lebanese economy, since the start of the conflict in Syria in 2011, and particularly after 2018. First, the party contributed to Lebanon’s growing cash economy through its reliance on informal financial actors.96 Hezbollah is also suspected of having played a role in cross-border smuggling with Syria during the years that followed the Lebanese financial crash in 2019, or facilitating it, when subsidized goods in Lebanon, such as fuel, medicine, and basic goods, were resold at a profit in Syria. These activities resulted in billions of dollars of losses to the economy. U.S. sanctions also shed light on Hezbollah’s links to currency exchange companies,97 seen as fronts allowing the party to bypass global restrictions on financial transactions and channel money to fund its activities.

Second, Hezbollah contributed to weakening the Lebanese government’s drug policies after the beginning of the Syrian conflict.98 While funding from Iran continued to flow to Hezbollah, even after U.S. sanctions heavily impacted Tehran’s resources and oil industry from 2018 onwards,99 the party used its influence to push for a laxer Lebanese approach to drug crimes, and this before the Syrian regime invested heavily in the Captagon trade. Hezbollah’s control of the Lebanese-Syrian border and its rejection of anything more than a cosmetic role for the state in managing crossings, contributed to the growth of the illicit trade. In fact, the party’s marginalization of the state in policing borders became systemic following the beginning of the war in Syria, and resulted in a situation where even the empty ritual of the annual destruction of hashish and opium fields in the Beqaa was discontinued.100

U.S. sanctions have targeted Hezbollah-affiliated individuals who had alleged ties with the Syrian army’s 4th Armored Division over Captagon production.101 While the Hezbollah connection has been related mainly to transporting or facilitating the movement of Captagon, recent sanctions have cited the party’s involvement in production activity inside Syria.102 Hezbollah’s role in Lebanon was an extension of the one it played in Syria, specifically in facilitating or turning a blind eye to the activity of drug traffickers. In the interrogations of Daqqou, the Hezbollah connection was obvious in the trafficker’s ability to coordinate the cross-border passage of drug consignments.103 Regardless of the level of evidence implicating the party, the fact that Hezbollah, which was present on both sides of the border, never stopped or hindered the movement of Captagon implied some form of involvement, while production also occurred in regions where the party maintained a military presence.104 Moreover, Hezbollah had connections to individuals involved in transnational connections, specifically with South America, whether in Venezuela, Mexico or in the triborder area between Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay.105 In Mexico for instance, a Hezbollah-affiliated operative, Ayman Jomaa, was linked to the Los Zetas drug cartel.106 This affiliation was behind U.S. pressure to shut down the operations of the Lebanese Canadian Bank in 2011.107 In various reports, researchers often attribute 20–30 percent of Hezbollah’s $1 billion in revenues both to donations from wealthy Shiite expatriates and to illicit dealings.108

The Captagon trade affected the Lebanese state in other ways as well, most significantly by harming its regional credibility and interests. In April 2021, Saudi Arabia froze fruit and vegetable imports from Lebanon after the authorities discovered a shipment of 5.3 million Captagon pills in pomegranate crates at Jeddah port.109 The rising tensions peaked when Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Beirut in October 2021 in retaliation for the then Lebanese information minister’s comments on the Yemen conflict.110 Such measures were taken partly because of the impact of the Captagon trade on Gulf societies, and more broadly because of Hezbollah’s sway in Lebanon and involvement in the Yemen war. For the Gulf states, these issues were linked. They viewed Captagon trafficking as a war waged against them by other means, particularly through networks in which Hezbollah—which supports Ansar Allah, the main enemy of Saudi Arabia and the UAE in Yemen—was involved. A shipment of 95 million Captagon pills to Saudi Arabia via Malaysia was attributed to Daqqou in 2021.111 Not coincidentally, this was the year the ISF Information Branch arrested him and launched an investigation into his activities.

In a sign of how Lebanon was caught up in a wider regional political game because of Captagon, in 2023 the Assad regime sought to leverage the Captagon problem to normalize relations with the Arab world after years of isolation.112 In fact, in May 2023 Saudi Arabia restored diplomatic ties with Syria, only two days after the Arab League had welcomed the country back into its fold. But this did not change the Syrian regime’s behavior. For it to have ceased drug production, it would have had to find lucrative alternative revenue sources. Given the regime’s weakness in Syria’s peripheries, from where the drugs were being smuggled into neighboring countries, as well as its reliance on militias and elite units of the Syrian army involved in Captagon production, limiting the drug trade would have required long-term structural changes inside Syria that it was either unwilling or incapable of addressing.

Despite the overthrow of the Assad regime, there are no guarantees that Captagon trafficking will stop. Jordan continues to be worried about the flow of Captagon in spite of the drop in production. The Jordanian authorities believe Captagon manufacturing facilities are continuing to operate in southern Syria.113 The prospect of a reduction in Iranian funding for Hezbollah following the conflict with Israel in September–November 2024, as well as the tremendous cost associated with funding its institutions and rebuilding areas of party control devastated by the Israelis, could even push the party to bolster its involvement in Captagon production. However, traffickers would need to play a major role in coordinating cross-border activities, as the factions on the Syrian side of the border are staunch enemies of Hezbollah. Much will also depend on the capacity of Lebanon and Syria to undermine the drug trade. With the recent election of Joseph Aoun as Lebanon’s president and a rise in international support for the country’s armed forces, it is highly probable that the state will increase its counter-narcotics efforts with tangible results.114 For the new Syrian government, which seeks a lifting of international sanctions, the challenge is even greater given its limited economic capacities and the need to unify the various factions now in control of border regions.

The regional and international response to post-Assad in Syria will impact the ability of Captagon networks in Lebanon to recover from the collapse of the Syrian regime and its 4th Armored Division, and from the weakening of Hezbollah. While the scale of production and logistical support may not reach the same levels as they did previously, Hezbollah’s financial needs and those of other political groups in Syria could mean that production and trafficking networks will survive. The Jordanian authorities have continued to target production facilities and smuggler networks.115 The fact that some Syrian opposition groups were involved in Captagon production and trafficking could suggest they may resume their activities, unless new policies and an economic recovery in Syria provide opportunities for alternative courses of action.

The prolongation of U.S. sanctions on Syria, even after the downfall of the Assad regime, may well create an economic environment that allows illicit networks to recover, albeit in a more decentralized way, which would be even more challenging to contain and could have potential spillover effects on Lebanon.116 The inability of Syria’s new leadership and institutions to control the country’s border regions as it musters resources to face emerging challenges elsewhere could also improve the conditions for Captagon trafficking. That is why the transition in Syria may be best addressed through a lifting of sanctions on the country and an increase in aid in order to improve living conditions. The decision of the European Union in January 2025 to begin easing sanctions on Syria was a positive step in this regard.117 Law enforcement will not be sufficient on its own to end to Captagon trafficking, as the example of Lebanon’s borders will confirm.

What happened in Lebanon may foreshadow what occurs in Syria. After the arrest of Rashaq in 2016 and Daqqou in April 2021, Captagon production and trafficking resumed, with the seizure of consignments to the Gulf market and the arrest of a major Iraqi drug trafficker in Beirut in 2024.118 The resumption of the Captagon trade and the trafficking networks’ scouting of new markets, such as Iraq,119 demonstrated their capacity to adapt. Lebanon’s financial and economic crises and the lack of political will to adopt reforms and place the country on the road to financial recovery will mean that the purchasing power of the security forces is likely to continue to deteriorate, rendering personnel more vulnerable to illicit networks. If the influence of Captagon networks grows, this could undermine the government’s ability to contain the drug trade, pushing foreign states to address the matter themselves. Given the divisions in society, this could harm Lebanon’s fragile civil peace. On the other hand, with the Syrian regime gone and Hezbollah weakened, there is an opening to address Captagon trafficking through sustainable economic means with regional and international backing.

One dimension of such an approach could be the long-term, equitable development of the northern Beqaa through support for existing agricultural projects and a revival of the tourism sector, which has been strangled due to security challenges and Hezbollah-imposed restrictions aimed at maintaining the party’s strict control over the region. Border clashes and lawlessness have led many Lebanese to stigmatize the northern Beqaa, discouraging them from visiting the area and enjoying what it has to offer. A more active state presence there could help restore its image as a cultural hub and the site of one the world’s most renowned Roman ruins in Baalbek.120 This would entail a multiyear investment to establish a viable economic alternative away from decades of reliance on drugs and smuggling.

Another policy route which has been suggested on the national level is expanding the legalization of Lebanese hashish and medical cannabis for export and implementing a 2020 law which focuses on its use in the medical industry. Regulating hashish and medical cannabis with state support could help the security services filter out Captagon production and trafficking networks. The government has not taken specific steps to implement the 2020 law, such as the formation of a commission with an authority to issue licenses.121 This is a policy option that had support in the Najib Mikati government and could provide an estimated revenue stream of $1.5 billion.122 The government and parliament were acting on a commissioned McKinsey & Company report,123 which recommended legalization to boost revenues for the state’s coffers.124 That is why the first government under Joseph Aoun’s presidency should push for implementation of such a law and expand it beyond medical use, selling hashish to countries where consumption is legal. Aoun, who in his inaugural speech promised to focus on fighting drug production and trafficking,125 should prioritize developing economic alternatives, alongside a crackdown on drug networks, to ensure a durable solution to the problem.

Captagon trafficking in Lebanon has reflected an interplay of local, national, and regional factors. The growth of the Captagon trade has presented new challenges for the country’s political system and has undermined the security services during years of economic stagnation, the conflict in Syria, as well as Lebanon’s financial collapse after 2019.

The security forces, with shrinking resources and depreciating salaries, have had to confront a more capable smuggling network, one with powerful local collaborators, cross-border connections, and an ability to maneuver around border controls. The impact of the Captagon trade negatively affected different categories of Lebanese exports, given the networks’ use of agricultural products, office supplies, fashion, food, and beverages to conceal their consignments. In the past three years, regional pressure has driven security responses to the Captagon network, but with few resources available for Lebanon’s institutions it would be difficult to expect continued success in the crackdown against trafficking.

While the downfall of the Syrian regime may create an opening to stem the Captagon trade, the traffickers’ supply chains, cross-border networks, smuggling routes, as well as continued demand abroad all represent significant challenges. Moreover, given the participation of former Syrian opposition groups in trafficking, Assad’s exit will not necessarily curb trafficking. Focusing on a strict security approach to the problem is not going to work if the current dire economic and financial conditions in Lebanon and Syria persist. Moreover, the countries’ law enforcement capacities will remain tied to the financial recovery in both states, which must sustain the budgets of the military and security services and the standard of living of their personnel. Without this, Captagon networks are likely to resume their activities.

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan

Recent leaks made public by Al-Jazeera suggest that this is the case, but the story may be more complicated.

Mohamad Fawaz