Over the past few years, Myanmar has broken away from strict military rule and engaged in a rapid political and economic transition that has attracted global attention. The government that came to power in 2011 embarked upon a series of democratic reforms, reaching out to civil society and opening up to the West.

Many observers believe that these reforms will lead to more distant relations with China, which has been Myanmar’s primary political and economic partner for decades. Yet while Myanmar’s democratic reforms may appear to signal a move toward the West, their success will in fact depend on Chinese economic engagement—a point that democracy activists should not overlook.

The United States normalized relations with Myanmar in early 2012 and has lifted most of its sanctions against the country. In November of that year, U.S. President Barack Obama paid an official visit to the country, the first by a sitting U.S. president. Since then, U.S. and European donors have provided generous assistance in the form of financial and institutional support. They have also helped prepare the country for its 2015 general election. Myanmar’s rapid political transition raises the hope that the country will soon become a Western-style democracy if it continues with its current reform agenda.On the economic front, Myanmar’s GDP growth rose from 5.5 percent in 2012 to 6.5 percent in 2013. The main drivers of this were increased gas production, strong commodity exports, and foreign direct investment after the lifting of sanctions.

However, economic reforms are fragile and have not advanced as fast as the political transition because structural economic change is lagging behind. The promised privatization of all the country’s state-owned enterprises has been moving slowly. As a result, inefficient state-owned enterprises still monopolize key sectors such as oil, telecommunications, and electricity. Businesses controlled by military interests have privileged market access.

This is particularly problematic because sustainable and broad-based economic growth is essential to political reform. The people of Myanmar anticipate a better quality of life as a result of the government’s transition, but these expectations depend on the creation of a healthy and sustainable economy. If economic reforms fail to raise the standard of living, frustrated citizens may turn on their new political leaders and systems and, however incorrectly, blame hasty political reform for slow economic change.

In addition, there could be serious consequences for the country if Myanmar’s economic reforms do not catch up to its political transition. The rapid increase in gas revenues is already causing high inflation in Myanmar. The country’s economy still depends largely on extractive industries, the wealth from which is not widely distributed because privileged interest groups seize the benefits for themselves, exacerbating the country’s income inequality.

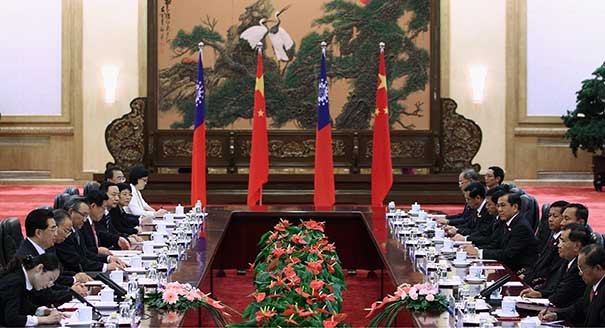

In order to ensure a peaceful and effective political transformation in Myanmar, the country has to improve its economy. Beyond moving forward on structural reforms, the government needs to actively engage China, which has an immense impact on Myanmar’s economic position.

Chinese economic activity is a significant driver of Myanmar’s growth and impacts various aspects of the country’s economy. China is not only the largest buyer of gas from Myanmar but also the source of deep-pocketed investors, numerous tourists, and affordable industrial products that fuel Myanmar’s economy.

If China’s demand for Myanmar’s resources recedes, or if Chinese investors become hesitant to establish factories in the country, Myanmar’s economy will suffer a significant blow. Western economic activity in Myanmar cannot replace China’s comprehensive engagement, as Western companies have only shown interest in limited economic sectors, like oil and gas.

Given the importance of solid economic growth, advocates of Myanmar’s political reforms must ensure that the country’s transition will not affect its relationship with China. Domestic political reform should not become an opportunity for foreign countries to expand their influence at China’s cost.

One high-profile case that may give the impression that democratization equates to distancing from China is that of the Myitsone Dam. The hydroelectric power project in northern Myanmar was planned by the state-owned China Power Investment Corporation, which provided a total investment of $3.6 billion. When the Myanmar government halted the project in September 2011 after protests over the dam’s environmental impact, many observers interpreted the incident as a fundamental change in Myanmar’s foreign policy. It was even compared to the color revolutions that took place in the former Soviet Union in the early 2000s, during which political change led to diplomatic hostility toward Russia. Such comparisons are dangerous and should be avoided, for they may arouse China’s suspicion and affect bilateral ties.

How can China be reassured that Myanmar’s political reforms will not damage Chinese interests? Crucially, the advocates of Myanmar’s political reform need to provide a more balanced picture to the public about Chinese activities in the country. Western media tends to exaggerate its coverage of the mistakes that China has made in Myanmar and fails to show how China has taken steps to address these problems or how Chinese engagement contributes to Myanmar’s economic growth. This dramatization makes China an obvious target of political criticism from Myanmar’s opposition party and civil society, which are heavily influenced by Western media. Hostility and suspicion then accumulate between China and Myanmar’s opposition—tensions that could be defused with the help of better-informed public opinion.

Democracy activists and supporters of Myanmar need a deeper understanding of the political and economic dynamics behind Chinese investment in Myanmar. As paradoxical as it may seem, Chinese investment is an indispensable condition for Myanmar’s further political reform.

This article was published as part of the Window into China series