Download the PDF

Russians have traditionally had strong yet contrary feelings about change, both longing for and fearing the transformation of the country. In the late 1980s, the last major era of radical change when the Soviet Communist system began to fall apart, the rock singer Viktor Tsoi sang words that all of Russia knew by heart: “Change! Our hearts demand it. Change! Our eyes demand it!” Attitudes are different now. After a long period of political stability dominated by one leader, President Vladimir Putin, the March 2018 election promises only a formal imitation of change, as Putin is universally expected to win another term. But against the backdrop of renewed protests, the Russian election raises the question of what will come next for the country as its long-serving leader begins his final term.

How do Russians understand the idea of change and how do they think it should come about? What kinds of changes do they welcome or dread? The Carnegie Moscow Center and the independent Russian polling organization the Levada Center posed these and many other questions in an August 2017 nationwide survey of roughly 1,600 Russians. They also explored these questions more deeply with four focus groups held in Moscow in July 2017.1

The survey revealed that many Russians do not exhibit strong enthusiasm for profound changes and often cannot articulate how the country’s trajectory should be amended. Yet, paradoxically, increasing numbers of them do not fiercely support the status quo, albeit for differing (and sometimes conflicting) reasons. The growing numbers of people who want modernization are mostly concentrated in urban centers and, above all, in Moscow. The return of protesters to Russian streets in 2017, and the modest success of the democratic opposition in Moscow’s September 2017 municipal elections, suggests that this dissatisfaction with the country’s current lot presumably will grow in Putin’s next presidential term and likely necessitate eventual changes in one form or another.

Yes to Change, But What Kind?

Many in Russia often view the absence of change as a positive, not a negative, phenomenon. Neither the country’s core ruling elite nor many ordinary Russians see a clear need for modernization, which they perceive to be a liberal project. Only liberals show a strong interest in this type of reform. Yet Putin has twice been the author of transformative change in Russia, just not of the liberal variety. In the early 2000s, he satisfied the population’s demand for a return to order and stability. In 2014, with his forced takeover of Crimea, he fed their yearning for a restoration of Russia’s great-power status. These changes have been designed to preserve the existing political system, not to reform it. Putin and his team see that they are earning popular acclaim not from modernizing, but from appealing to the archaic and keeping things as they are. In 2018, they will only be willing to make small (mainly economic) policy adjustments. They are keenly aware of what happened to perestroika, the reform project of the late 1980s, when then Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev started a process of democratization only to lose power.

The first big conclusion Carnegie and Levada’s survey data revealed is that many Russians say they want change, but different groups’ understandings of the concept vary widely (see figure 1). The vast majority of respondents—more than 80 percent—say they want to see some degree of change: 42 percent reported a desire for radical, comprehensive change, and another 41 percent expressed a desire for incremental, gradual improvements. Only 11 percent said they preferred that everything be left as is it.

The survey indicated that the largest social group that wants “decisive change” in Russia is those who have gained the least from the existing order. These individuals tend to be at least fifty-five-years old, poor, and without higher education, and they generally live in towns with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants.2 These people have no interest in economic liberalization. They simply want to live better. The irony of their situation is that this social group is the least capable of understanding which policies would improve their personal circumstances, and this makes them perfect targets for populist politicians.

Few who advocate radical change can be classified as liberals and democrats, the social group that wants to see a more law-based, open political system in Russia.3 The gradualists are a larger, more diverse group that favors incremental change. Many of them support Putin and the existing political order, have college degrees, and are relatively affluent. They may want to fix a few minor problems, but they fear that a complete overhaul of the status quo could threaten their quality of life. This group would welcome a rational road map of nonradical reforms, if one were on offer.

Moscow is a case unto itself. Its citizens combine a preference for small, gradual changes with staunchly liberal views on the need for judicial reform, free elections, and media freedoms. The information-rich, relatively free environment of Russia’s largest city allows Muscovites to think more deeply about their ambitions. However, there are also plenty of people in Moscow, even some liberals, who support tighter state regulation of the economy.

The Russians polled widely believe that young people are the group most interested in change (see table 1). But this supposition is not supported by the facts.

In reality, contrary to any preconceptions that young people are the drivers and advocates of change, they are perhaps the most conservative group on this issue. Survey findings showed that fewer (34 percent) young people, aged twenty-five years and under, are strongly in favor of decisive, far-reaching change than any other age group.4 Young people are also the most likely to say that no change at all is necessary (15 percent of respondents, compared with roughly 10 percent of other age groups). Almost half of young people believe that Russia needs only minor changes.

Why is this the case? It may be because this generation grew up under Putin, knows no other leader or political system, and has not experienced other state models. Support for the government has been higher among young people than the national average. However, when young people become adults (twenty-five- to thirty-nine-years old) with careers and are then responsible for their own lives and families, their desire for change seems to grow.

Yearning for a Better Life

The survey results also revealed a consensus across all societal groups that Russian leaders must prioritize the public’s material well-being (see figure 2).5 Most respondents want to see higher living standards and greater justice. When survey participants were asked what reforms they would like to see, some of the most common responses were measures that would result in “a better quality of life for ordinary people,” “higher incomes for Russians,” “improved welfare of the population,” and “increases in salaries and pensions.”

Similarly, many of the Moscow focus group participants wanted Russia to shift its focus from foreign affairs to domestic policy. Even members of Moscow’s middle class mentioned wistfully that they would like the government to look after them more. Some contrasted the policies of the oil-rich leaders of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates with those of Russia’s leaders, saying that the latter “don’t love their people and are trying to fleece them.”6 Some Russians seem to mythologize oil-rich Arab countries as models of fair redistribution of oil revenues that allow people to work less, receive more money, and live better.

A desire for state payments and state-imposed price controls cannot be fully explained as a public longing for state paternalism. It reveals a symptom of dissatisfaction with Russia’s status quo, combined with a lack of understanding about what should be done. (See table 2 for a breakdown of what policy priorities survey respondents believe their government should focus on.) This outlook reveals that many Russians, including many individuals from progressive groups, feel disoriented and lack a basic understanding of how an economy works. This apparent disconnect may help explain why the very same people can simultaneously say they want to see the reimposition of state economic regulations, while also believing that the main achievement of the early 1990s was the appearance of sausage (a symbol of the success of liberal reforms) on store shelves.

Meanwhile, Muscovites name the goals of fighting against corruption and fostering economic development two or three times more frequently than inhabitants of other parts of Russia do. One in five Moscow residents said they want to see free and fair elections.7

The near unanimity on the role of the state is likely due to the almost complete absence of public debate in Russia about the reform process. Many people form opinions by watching the populist hosts of national television talk shows—such as Vladimir Soloviev, Dmitry Kiselyov, and Nikita Mikhalkov—rather than listening to experts and specialists.8 The problem is not the illiberal ideas these figures expound so much as their hysterical, hateful, aggressive language.

The liberal respondents in the focus groups believe that people like them want to see change the most. They understand relatively well how the general public regards change. One member of an older liberal focus group said, “I think that most people want change. Probably about 80 percent want change. The trouble is everyone is afraid of these changes. . . . Everyone wants changes without revolutions, without upheavals.” Another member of this focus group remarked that many people want change that turns the clock back:

“I am in touch with people who work in small remote towns in the European part of Russia. People there want change, too. But they want a very different kind of change. They want the government to get stronger, they want all rich people to be shot, they want kind Comrade Stalin to come back and save everyone. That would be change, too.”

Other groups had quite different views on change. Members of a younger, more conservative focus group want to see national wealth redistribution away from one or two percent of the population to the general public. One such respondent said, “We need to develop domestic production, create jobs, and fight the phenomenon of labor migration, which drags down wages.” The older conservative group wanted to see a fight against corruption through a much more punitive justice system. Meanwhile, many members of the Moscow focus groups, of different ages and ideologies, again stand out for advocating radical change. A focus group moderator asked, “The changes that you named, are they even feasible at all in our country?” The young liberals offered a series of ambitious answers, such as: “Perhaps if we change the entire system, from top to bottom”; “if we tear it all down”; “only if we change the existing regime”; and “well, it’s like the Berlin Wall—once it came down, everything changed.”

The Cost of Improvement

While many Russians concur that the status quo is untenable, disputes arise over what should be done to improve economic and other domestic policies. One constant is that all groups stress the passivity of both the authorities and the people. As one focus group participant put it, “Most people want change, but don’t want to do anything to make [such changes] happen,” and “they are afraid that things will only get worse.”

Reforms come at a cost. Naturally, no one wants to pay for such changes, as everyone would prefer that someone else bankroll them. One member of an older liberal focus group declared, “Usually, people say that ordinary people should pay the price for reforms. Why can’t the oligarchs pay this price?” Strikingly, there was a consistently negative view of both the era under former president Boris Yeltsin and Yegor Gaidar’s 1992–1993 economic reforms. In a December 2015 Levada poll, only 11 percent of respondents had favorable feelings about them. The public opinion survey confirmed that many respondents exhibited little willingness to bear even small costs for the sake of change (see table 3). Respondents were most receptive to adjusting to new technologies and acquiring relevant skills: 64 percent of respondents said they were at least somewhat willing to adapt to technological change (27 percent said they were not). They were far less open to other changes.

Many were especially reluctant to countenance any change in social benefits: 77 percent were not willing to relinquish some benefits today for a better life in the future (compared to 16 percent who were). The urban, middle-aged, middle class—particularly individuals between ages twenty-five and thirty-nine and residents of big cities—were most amenable to paying extra for higher-quality services. City dwellers were also more willing than others to put up with the closure of unprofitable enterprises. Overall, these views seem to suggest not so much a belief in paternalism as a clear conviction that the state must bear the burden of social obligations—that the state owes its citizens something.

Who Is Mister Reformer?

Efforts to understand what changes different segments of the Russian population might support raise the question of which public figures might carry the banner of reform. Asked to list past Russian reformers, focus group participants in Moscow often mentioned Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, Alexander II, and Pyotr Stolypin—citing names from their childhood history textbooks with the benefit of a post-Soviet perspective. All Soviet and post-Soviet leaders made the list, including Stalin. But the key economic reformer of the 1990s, Yegor Gaidar, was only mentioned once, remaining in the shadow of his political patron, Boris Yeltsin. When asked whose reforms were successful, almost everyone named Peter the Great. Respondents identified successful reformers as those that strengthen and consolidate the state and increase its military might. It is revealing that Peter the Great made the cut, but Gorbachev and Yeltsin did not. One participant remarked, “Peter [the Great] was a father of the state, he was a true leader. Gorbachev and Yeltsin weren’t. Would one really call either of them a father of Russia?”

Focus group members understood that liberalization took place under Khrushchev, Gorbachev, and Yeltsin, but even liberal participants did not always approve of their actions. The persistent preconception that these leaders wrecked everything has become hardwired into mass consciousness. The same is true of the mythic portrayal of the 1990s as a time of chaos for Russia. When pressed for details about this era, focus group members did recall that this was when the country gained economic freedom and private property, when food appeared on store shelves, and when Russians achieved freedom of movement and freedom in general. As one participant stated, “Everyone won. You can’t even compare Communism with this. Has everyone forgotten that [under Communism] you couldn’t just buy a car or take a trip abroad?” Asked to list countries that are successful models of reform, respondents named a diverse group of states, including Georgia, Germany, and South Korea.9 However, they mostly agreed (with a certain fatalism) that Russia has botched its own reform efforts. The widespread view was that no one in contemporary Russia has successfully conducted reforms and no one ever will.

Why have reforms failed? Members of focus groups generally said that the reforms were never completed. Moreover, some asserted that transformations tend to claim “victims” and that those “close to the gravy train” often oppose change. Besides, others claimed, Russia is simply too vast for successful change to take hold. Some believed that reformers do not know how to talk to the people, and that they do not explain what they want to do and how. This last criticism came from the most progressive respondents, who seemed to watch events from a distance, reluctant to get involved. This typical psychological malady seems to stem from people voicing support for reforms in principle, but viewing it as someone else’s responsibility to carry them out.

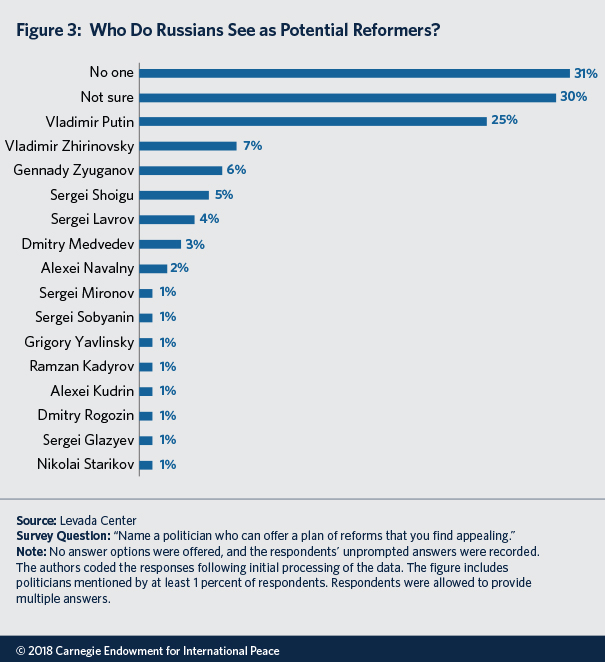

Given this skepticism, it is not surprising that, when survey respondents were asked to name Russia’s most successful current reformer, the most common response was “no one.” A total of 61 percent of participants could not name a single politician who offered a plan for change that they liked (see figure 3).

The next most popular choice was Putin. Significantly, there is no debate about Putin. Almost no one questions his legitimacy as president. He is a constant, the portrait on the wall that can no longer be taken down. As there is no political alternative to Putin, one-quarter of respondents expressed the belief that he is capable of proposing and initiating reforms. The number was higher among young people, well-educated individuals, and inhabitants of big cities.10 That suggests that more progressive individuals are still grateful to Putin for his past achievements and do not demand the impossible, such as the appearance of an alternative political figure. Moreover, many in Russia’s middle class are employed by the state in some capacity and depend on the state for their well-being.

Focus group participants were also willing to forgive Putin a lot; as one participant conceded, “even Putin can’t fix these problems.” The idea that Putin cannot be displaced reveals an underlying, largely unspoken recognition and passive acceptance of the existing authoritarian regime. Putin is still reaping the benefits of renewed legitimacy following the 2014 takeover of Crimea. Six months before the next presidential election, 52 percent of Russians were ready to vote for Putin—almost twice as many as at the same time in the 2012 electoral cycle.

Politics Still Matters

Ultimately, the survey results pose a challenge to Russia’s ruling regime. Contrary to the widespread belief that Russian elections, being rigged in advance, have been completely discredited, many people nonetheless believe in them as an instrument of change (see table 4). In fact, the largest plurality of respondents (43 percent) said they believed in the need “to vote for parties/candidates that offer a plan of changes that [they] most prefer.” This included the most progressive groups: individuals aged twenty-five to thirty-nine who hold college degrees, have high incomes, work in management, and use the internet daily. The same held true for residents of Moscow, the country’s most active place in terms of efforts to effect change, thanks perhaps to the city’s positive trends of civic activism. Roughly 69 percent of Muscovites think that voting is the optimal means of achieving change, compared to 36 percent in small cities and rural areas.

Fewer respondents indicated willingness to take more active steps. Between 16 and 21 percent said they would “take part in the work of public and political organizations,” “submit complaints and suggestions to government agencies,” or “sign open letters and petitions.” These approaches allow citizens to call the government’s attention to problems and urge officials to address them, while personally remaining on the sidelines. A member of one focus group who believes that public passivity is the main obstacle to change but still trusts in Putin said, “Most people want changes, but don’t want to do anything to make them happen.” Incidentally, 12 percent of respondents said that they would “volunteer for public and political organizations or causes.” This is a fairly significant percentage, given that this kind of volunteering requires a commitment of time and energy, is unpaid, and can be dangerous either physically (in the case of firefighting, for example) or politically (given that the authorities often punish citizens for unsanctioned volunteer activities).

Citizens willing to engage in overt political activism comprise a still smaller minority. Relatively few people—8 percent—said they were willing to take part in protests, while only 4 percent of respondents were willing to donate money to public and political organizations or projects, although, again, these numbers were much higher among the young, educated individuals, and residents of Moscow.

Conclusion

Collectively, these survey and focus group results reveal a paradox. Most Russian citizens do not express a strong desire for sweeping change and do not have in mind a specific road map for reforms. They lack a clear idea of who can offer reforms and how to carry them out most painlessly. And yet most Russians (including the post-Crimea, pro-Putin majority) understand that the country cannot move forward, or even stay in place, without reforms. Russian elites, whose primary objective is to remain in power after 2018, need to understand that their traditional adaptive strategies (ultraconservatism and state involvement in all aspects of public life) ultimately do not work. If they want to secure the public’s trust, these authorities will ultimately have to change themselves one way or another.

Notes

1 The Levada Center survey polled 1,602 Russians over the age of eighteen. The four focus groups of eight individuals were composed, respectively, of young liberals, older liberals, young conservatives, and older conservatives.

2 These observations are based on the underlying Carnegie-Levada survey data.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 The authors noted that respondents seemed particularly interested in this question’s topic—some interviewees provided five or six answers, and most provided at least three. Such enthusiasm in answering survey questions is rare. It appears that the authors touched on a topic that is very important to the respondents. The authors of the report coded the responses after an initial processing of the data.

6 This and the following quotations come from the focus group discussions.

7 These numbers are drawn from the underlying Carnegie-Levada survey data.

8 Ibid.

9 This information comes from the July 2017 focus group discussions in Moscow.

10 These observations are grounded in the underlying Carnegie-Levada survey data.