Less than a year ago, concern mounted over the seemingly unstoppable rise of Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), as the party climbed to new heights in opinion polls. Only the Greens registered a similar rise in support. By September 2018, some polls found that the AfD was the second-most popular party in Germany. Political commentators began discussing a grand realignment of the German party system, where increasing polarization would turn two polar opposites—the cosmopolitan Greens and the nationalist AfD—into the new Volksparteien (people’s parties).

The German political system seemed set for a vicious cycle. As the AfD enjoyed more support, less political space remained for the other parties. Grand coalitions between Germany’s major parties became more likely, which, in turn, confirmed AfD supporters’ belief that other parties do not present any real alternatives and only the AfD can offer opposition.

That expectation has not come to pass. Germany seems to have escaped its vicious cycle. According to the latest opinion polls, political standings are more or less back to where they were in the 2017 federal elections (only the Greens still enjoy a higher degree of support than before): the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) at around 30 percent, the Social Democrat Party (SPD) and Greens at around 20 percent, the AfD at around 12 percent, and the Left and the Liberal parties at around 8 percent. The recent European Parliament election results are less comparable as turnout is always much lower than in federal elections. Certainly, Germany is not on the brink of a nationalist surge. A string of elections later this year in eastern German states (Sachsen, Thüringen, and Brandenburg), where the AfD is generally stronger, will likely result in the party receiving around 20–25 percent of votes, which could trigger more hyperbolic reporting on the rise of the far right. But recent years have provided Germany with valuable lessons on how to respond: a mix of political and institutional reactions, related to the German concept of militant democracy, have undercut the AfD and quieted concerns about democracy in Germany.

The AfD’s Resurrection in 2015

The AfD faced irrelevance in the summer of 2015. The party had been launched in 2013 by middle-class economic liberals who objected to the government’s policies to save the euro. The old Euroskeptic AfD gained 7 percent in the 2014 European Parliament elections and 10–12 percent in three eastern state elections the same year.

In 2015, the party splintered. A number of members, including the party’s chairman, left, believing that the AfD had become too extremist. When then minister of finance Wolfgang Schäuble convinced most conservative voters that he had held a firm line in debt crisis negotiations with Greece in July 2015, support for the AfD dwindled even more. The party reached rock bottom with public support at only about 3 percent, well under the 5 percent threshold necessary to enter parliament.

The 2015 refugee crisis changed things. Chancellor Angela Merkel, who had shown little interest in refugee issues before and whose government had tightened asylum laws in June 2015, announced “we will manage” the increasing flow of refugees and migrants—somewhat contrary to her image as a cool tactician—and did not close Germany’s borders in September 2015.

Merkel’s coalition partner, the Bavarian CSU, was uneasy with her decision but did not obstruct the policy. Indeed, no party in parliament voiced serious reservations in the first months, as nearly 900,000 migrants came to Germany by the end of 2015. Instead, Merkel rode a wave of public support fanned by the media, including tabloids like Bild, which ran a campaign with the English slogan “refugees welcome.” The mood changed when the government failed to communicate a plan to end the exceptional situation and after more than a thousand women were allegedly sexually assaulted or harassed in Germany on the night of December 31, 2015, by groups of men that included mostly migrants and asylum seekers.

Only the AfD voiced complete opposition to Merkel’s policy. In 2015, democracy functioned as usual: an important opinion, which attracted increasing support, was nowhere to be seen in parliament, so voters turned to an outsider party. The AfD’s subsequent rise appeared inevitable.

But new party leaders had put the AfD on a more extremist course, and the refugee crisis fanned the flames. In 2016, the party won more than 20 percent of votes in elections in eastern states and around 15 percent in western state election. In the 2017 federal elections, it received 12 percent of the votes.1

By 2018, the AfD’s ascendancy appeared unstoppable. According to September 2018 opinion polls, it had become the second-most popular party with 18 percent support. It particularly benefited from the Social Democrats’ decline. Since late 2015, the AfD had successfully set the public agenda: immigration began to dominate the evening talk shows after the summer of 2015, and the leading public TV talks shows covered issues like government weakness, Merkel, or migration more than thirty times in 2018, with little coverage of global warming despite a significant draught.

The debate reached fever pitch ahead of the Bavarian elections in September 2018. Increasingly, it appeared that the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, the CSU, would start imitating the AfD. Its leader, Horst Seehofer, frustrated that Merkel had given him few policies to appease the CSU’s conservative voters, declared “migration as the mother of all problems.”

Stoppable After All?

Today, the picture has changed. The AfD registers around 12 percent in opinion polls,2 which would make it the fourth-largest party in parliament. What has changed? In short: the reality on the ground has shifted, the party’s opponents have become more skillful, and the state has started to respond.

Migration across Europe is down. For a while, this development went strangely underreported in Germany’s public debate. Merkel basked in the glow of her compassionate policies in 2015 and was not interested in now claiming responsibility for the EU’s hardened external borders. And the AfD had an interest in portraying migration as an ongoing crisis. The reality of stricter EU immigration policies served neither party, but it has finally made an impression on the public.

The reduced number of migrants alleviated the public split between the CDU and CSU. As political scientist Timo Lochocki has argued, democratic right-wing parties can undermine the far right if they address hot-button issues like migration effectively and visibly. The CDU and CSU, as he points out, had spent two years doing the opposite: the sister parties argued publicly, which exacerbated the problem and signaled that the government was bickering instead of taking control—a boon for any far-right party looking to make gains.3

Another significant factor in the AfD’s decline was Merkel’s decision to withdraw as CDU chairwoman and stand down from the next race for Germany’s chancellorship. Her announcement deprived the AfD of its favorite bogeyman, having portrayed Merkel as a power-hungry politician bent on destroying Germany. The ensuing lively CDU leadership contest, which attracted much public interest, belied the AfD’s claims that the party system was sclerotic. The new leader of the CDU, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, has made outward appeals to cultural conservatives in her party since she was elected. For once, the public debate was not centered on the AfD and its statements but on the CDU.

With the Christian Democrats actively reintegrating conservative voters, the SPD returned to life as well, becoming more vocal about its traditional socioeconomic themes, pushing for higher pensions for low-income earners, and advocating for measures to reduce the lack of housing in large cities. The AfD’s silver bullet—making any political issue a cultural referendum on migration and Islam—was poison to the SPD, whose electorate combines traditional workers and younger, urban liberals. Cultural and identity issues are the wedge that divides these groups. But the reverse is also true: Social Democrat voters are more united on the socioeconomic issues that divide the AfD. Contrary to popular belief, the AfD’s voters are not economically downtrodden, rather they represent a whole range on the economic spectrum.

Finally, the German constitutional concept of militant democracy finally showed its teeth. In most countries, politicians and social norms are expected to keep extremists at bay. The authors of Germany’s constitution, traumatized by the experience of 1933, fortified the state’s institutions with the duty and defined powers to resist forces in society that threaten to undermine the democratic order.

In January 2019, Germany’s internal security agency (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV, which literally translates to Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution) announced that the AfD warranted potential investigation and that it would monitor the party’s youth wing and its most extremist internal faction, organized around Björn Höcke. This was doubly problematic for the AfD. On the one hand, it unsettled members of the party, especially those who work for the state and fear that their membership may become a professional liability. On the other hand, it finally focused the public’s attention on how and where the AfD had overstepped the boundaries of Germany’s constitution.

Before the federal agency stepped in, the AfD could easily dismiss criticism as politically motivated and partisan. Indeed, many journalists made life easier for the AfD by not distinguishing which facets of the party were antidemocratic as opposed to very conservative. The BfV’s 436-page dossier shed light on aspects of the party that run contrary to democracy. Any party can argue against immigration or be opposed to the EU within the confines of German democracy. But while the AfD’s program is generally in line with constitutional provisions, leading party members regularly make statements that violate constitutional principles.

As the BfV noted, AfD leaders and other members frequently frame their position on immigration by denigrating minorities and consider them second-class citizens at best. They employ an ethnic narrative around what it means to be German that is inconsistent with the civic framing of the German constitution. Some party members also argue in racist terms, going as far as to claim that immigration is equivalent to a genocide of the German people—with no penalty from party leadership.

In their attacks on Islam, leading party members go well beyond what could be considered reasonable critique of a religion. Some argue that Islam should have no future in Europe; others claim that Islam is not a religion at all. These positions threaten Germany’s constitutionally guaranteed freedom of religion.

In some wings of the AfD, even Germany’s constitutional democracy is questioned. Members regularly compare “the current system” to the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR). The absurd comparison—opponents of the GDR were sent to prison, while the AfD opines from the sofas of Germany’s tax-funded evening talk shows—suggests the party aspires to a system that is not democratic.

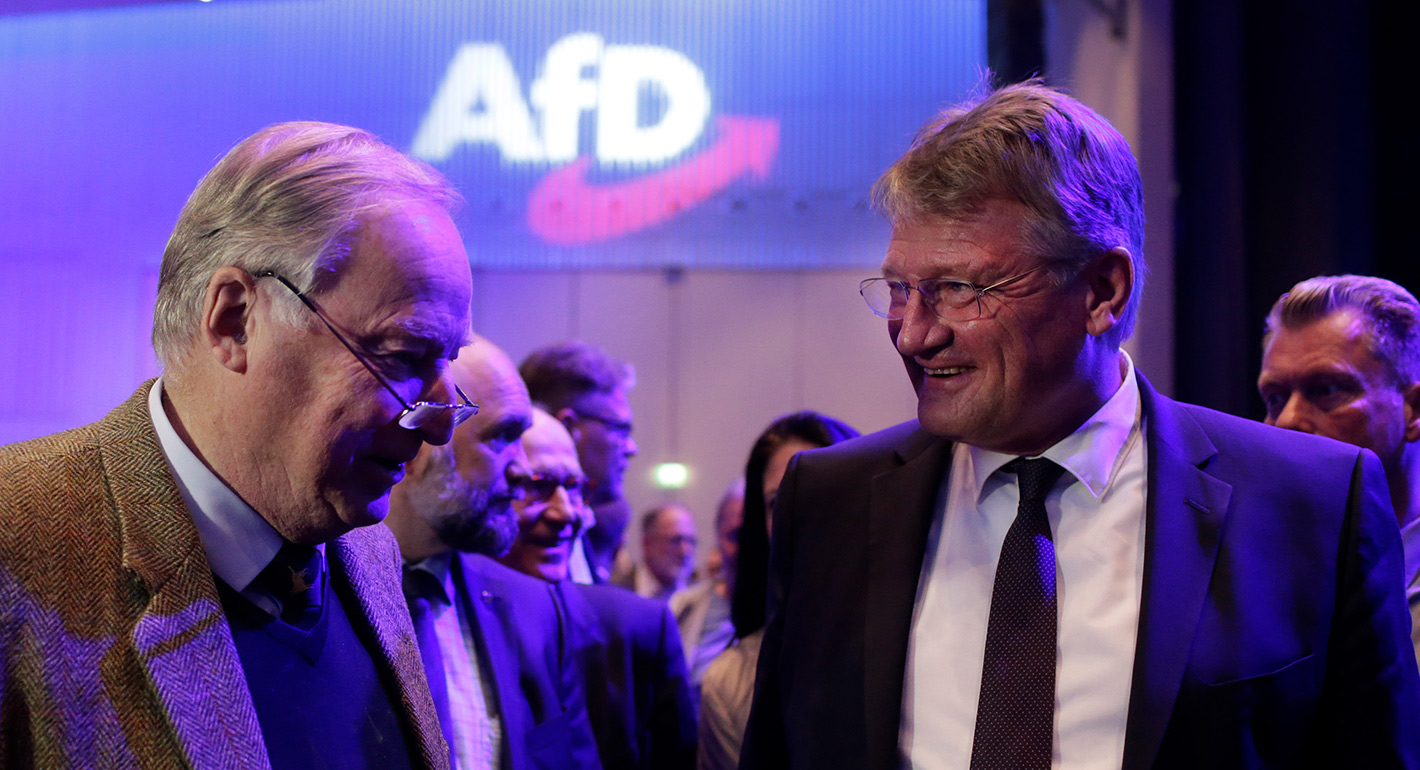

Leading AfD members also object to the way German culture approaches its Nazi past, arguing that history teachers should highlight more positive aspects of Germany’s legacy. In a speech last year, AfD chairman Alexander Gauland claimed that Germany’s twelve years of Nazi rule were mere “birdshit in 1000 years of successful history.” Considering the AfD’s many ambiguous statements on political violence, it has becomes clear that the party has extremist tendencies.

Lessons and Outlook

The German political scene has matured to the challenge of the AfD, a sizable party with extremist tendencies. Some media appear to support the AfD’s far-right agenda. Most notably, Bild reversed course from its “refugees welcome” campaign in 2015 and made immigration-related crimes and issues a prominent and permanent part of its news coverage—a case of highly selective reporting. But most media and politicians have become less likely to respond to every provocation, making it harder for the AfD to set the agenda. And there is mounting unrest inside the party, particularly due to the BfV’s investigation. But while AfD leaders occasionally try to exclude more extremist members, their steps are half-hearted and their statements tepid. It is more likely that AfD will sacrifice moderate support than abandon its extremist flank.

The AfD’s rise has been stopped for now. The situation looks less dramatic than it did six months ago. But only four years ago, the party had seemed to fade entirely out of the political picture. Contrary to long-held beliefs, Germany is not immune to far-right politics.

With its own network of media, the AfD is becoming an established part of the German political scene and well-integrated into the globalized extreme right. New circumstances could propel the party upward again, reducing other parties’ ability to form coalitions and again setting in motion that vicious cycle.

The German political scene has become less consensus-oriented than it was during the last decade. The party system has grown to six parties with stable support beyond the 5 percent threshold. All parties have defined their agenda more clearly, offering greater contrast with their rivals. The CDU may adjust the centrist course it adopted under Merkel; it appears to be moving cautiously to the right under Kramp-Karrenbauer, at least on issues of identity. After eleven years of grand coalition governments since 2005, a less centrist government—from either side of the spectrum—might refresh German democracy.

Germans are less confident than they were ten years ago. Germany’s geopolitical environment is deteriorating quickly, the immediate economic outlook is worsening, and there are doubts whether core German industries have a future. Berlin’s start-ups may dream of becoming the next Facebook, but Germany’s industrial giants fear becoming the next Nokia.

Will domestic politics be added to the list of existential threats? Not if Germans can revive political competition without losing the stability that is based around some foundational consensus. Other political parties must stop giving the AfD so much attention and provide voters with more identifiable alternatives. Germany needs more meaningful competition within the democratic spectrum.

Based on these trends, it was not surprising that the AfD only received 10.9 percent in the European Parliament elections, although low turnout is another explanation. Polling data show that almost 2 million of its supporters did not turn to other parties, they merely stayed at home. In national elections, turnout is much higher. The more critical test will be parliamentary elections in three eastern states—Brandenburg, Sachsen, and Thüringen—in fall 2019. It is possible that the AfD becomes the strongest party in these state parliaments. Almost thirty years after the reunification of Germany, there are still significant differences in political temperament between many West and East Germans. German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in 1989, called East Germany’s uprisings a “catch-up revolution,” a somewhat arrogant label that implied the West had nothing to learn and that the East would adjust. It has not turned out to be so simple.

East Germans have shown themselves to be far more skeptical of Germany’s democracy than West Germans. In a 2019 poll, only 42 percent of East Germans expressed their confidence in the current form of German democracy, compared to 77 percent of West Germans. East Germans have tangible grievances—such as a significant underrepresentation in the higher echelons of the federal bureaucracy—but most of the differences stem from mentality.

Many East Germans expect more from the state and are consequentially more critical of its shortcomings. As East Germans idealized Western democracy during communist times, some disappointment may have been inevitable. But German democracy offers space for any political program—even law-and-order conservatism—as long as it does not cross into political extremism. The challenge, then, is how to appeal to this electorate while drawing clear redlines against the kind of extremism promoted by the AfD. For deeper change, some form of national dialogue that reviews the history of reunification and differences between East and West Germans is overdue.

Michael Meyer-Resende is executive director for Democracy Reporting International in Berlin.

This article is part of the Reshaping European Democracy project, an initiative of Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program and Carnegie Europe.

Notes

1 Timo Lochocki, Die Vertrauensformel (Freiburg: Herde, 2018).

2 Situation in May 2019. For data, see Lochocki, Die Vertrauensformel.

3 Lochocki, Die Vertrauensformel.