Chapter 1: Sovereign Wealth Funds and Ongoing Corruption, Illicit Finance, and Governance Risks

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) have existed for more than a century, typically as state-sponsored financial institutions that manage a country’s budgetary surplus, accrue profit, and protect a country’s wealth for future generations.1 Yet, for the economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), SWFs only burst into public consciousness in the mid-2000s, when widespread concerns arose that SWFs with large amounts of capital could control strategically important assets and threaten the national security of countries where they deployed their investments.2

The term SWF itself refers to money that is invested by a country in order to protect it from economic shocks or to save it for future generations. The institutions featured in this paper have been included and classified as SWFs if they are members of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF), if leading investor subscription services like the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute have categorized them as SWFs, or if cases or investigations have referenced them as SWFs. Only vehicles owned by a country’s national government have been included.

Early SWFs were set up in countries whose economies were reliant on exporting natural resources like oil, phosphate, and copper (for example, Chile, Kiribati, Kuwait, and Norway). Governments wanted to create a mechanism by which excess revenues generated when commodity prices were high could act as a buffer when there was an economic downturn. SWF investments also helped smooth out budgets, as the prices of those exports could rise and fall on international markets. SWF funding sources have expanded to include any surplus from foreign reserves, budgets, a country’s central bank reserves, public-private partnerships, or citizenship-by-investment schemes.

In the 1990s, SWFs held merely $500 billion in assets,3 but by 2020, they had more than $7.5 trillion in assets under management (AUM), equal to about 7 percent of the global AUM of $111.2 trillion.4 This exponential growth in SWF investments has seemingly ignored many potential systemic corruption and other governance challenges. As outlined in this chapter and those that follow, SWFs are often found in countries with high risks of corruption and significant governance challenges including poor rule of law. And because SWFs are usually completely under the control of governments, they can be used to pursue purely political goals. Moreover, SWFs often have no fiduciary responsibilities or minimal reporting obligations, making it difficult to understand where a country’s money is invested. Despite SWFs being publicly financed entities, they are not subject to rigorous international financial disclosure and accountability mechanisms that would check for issues such as corruption. There is also a substantial network of intermediaries (financial experts and professionals) that help SWFs invest, which, as this paper documents, can raise the risk of corruption and other governance challenges, if there is poor oversight and accountability. Basically, SWFs are only subject to voluntary self-regulation, and so far, as of 2021 twenty-nine SWFs—which account for roughly 80 percent of all SWF assets—are only in partial compliance with the self-assessment standards set out by IFSWF.5

Public consciousness of SWFs, their roles in economies, and their potential political impact grew during the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. Some SWFs played a “white knight” role to several Western financial institutions, providing large capital infusions to banks facing bankruptcy.6 In the first six months of 2008, SWFs injected more than $80 billion into Barclays, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and UBS, stabilizing the global credit market.7 At the same time, however, these large investments drew much more public scrutiny to SWFs. Yet, most of the international, government, and academic discourse since then has centered around the impact of SWFs on corporate governance, financial market stability, and national security risks—with corruption risks rarely being discussed.

The potential for SWFs to be used for grand corruption and kleptocracy first gained widespread attention in the early 2010s due to a scandal involving a Malaysian SWF called 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), which is described in detail in chapter 3. Under former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak and a financier named Jho Low, a series of con artists, bankers, Malaysian elites, and even Hollywood movie stars benefited from the diversion of more than $4 billion in funds from Malaysia’s 1MDB SWF.8 As media reports began to highlight troubling issues with the fund and as the U.S. Department of Justice launched an investigation, 1MDB found it difficult to use the international banking system. However, elites from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates came to the rescue, using their personal reputations and their own SWFs to help 1MDB continue to launder funds.

In the wake of that headline-grabbing corruption scandal, the question that remains unanswered is whether current research, government regulation, and international standards can adequately deal with the corruption and other governance risks that SWFs present. Using case studies of SWFs from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, the chapters in this compilation demonstrate that enduring systemic governance issues and regulatory gaps have enabled SWFs to act as conduits of corruption, money laundering, and other illicit activities. For SWFs to achieve their full potential, reform is needed not only at the institutional level of the SWF but also across the variety of actors and jurisdictions that make up the supply chain of SWF activity.

This introductory chapter is intended to help set the scene for what is a complex topic. The chapter presents an overview of SWFs, the potential risks of corruption and rent-seeking activities, and the impact these behaviors can have on a country’s citizens. The chapter also demonstrates how SWFs have evolved, how they are funded, where and how they invest, and the current international and domestic regulatory landscape. Finally, it summarizes the different SWFs examined and the recommendations for helping them reach their potential.

What’s in a Name: Challenges With Defining a SWF

Any discussion of SWFs is incomplete without addressing an ever-present definitional conundrum. Though recognized SWFs like the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) have been around since the 1950s,9 the term “sovereign wealth fund” emerged only in 2005,10 when it was coined by financial analyst Andrew Rozanov as a way to differentiate SWFs from other institutional investors.11 Since then, however, international organizations, governments, and academics have all created and employed slightly different definitions of the term SWF.12 The lack of a clear, single definition makes monitoring SWFs for money laundering, corruption, and other rent-seeking especially challenging because there is no uniform way to provide guidance on potential risks and to identify what financial behavior should be monitored and assessed. The differences in SWF definitions have also prevented states from maximizing their combined efforts in countering illicit acts.

Perhaps the best-recognized definition is the one contained in the Generally Accepted Principles and Practices (GAPP) that govern SWFs, otherwise known as the Santiago Principles. Drafted by the International Working Group on SWFs, the Santiago Principles define SWFs as “special-purpose investment funds or arrangements that are owned by the general government.”13 Created for macroeconomic purposes, SWFs hold, manage, or administer assets to achieve financial objectives and employ a set of investment strategies that include investing in foreign financial assets. SWFs are commonly established out of balance-of-payments surpluses, official foreign currency operations, the proceeds of privatizations, fiscal surpluses, and/or receipts resulting from commodity exports.

The Santiago Principles are considered global foundational standards under which SWFs have committed themselves to operate. A key element of the SWF definition is that the fund must be owned by a national or subregional government. For example, a fund owned by the state of Alaska would qualify as an SWF because it was owned by a state government within the United States. The next criterion is that the vehicle’s investments must include foreign investments. Therefore, any fund with a mandate to invest all its money domestically would not be considered an SWF. By that measure, the Türkiye Wealth Fund (discussed in chapter 8 of this compilation) would not usually be considered a SWF, as it has a purely domestic mandate. But to ensure consistency across the cases presented here, entities treated as SWFs in practice, such as the Turkish fund, are also included. Appendix A provides a more detailed discussion of various SWF definitions.

The Growth and Evolution of SWFs

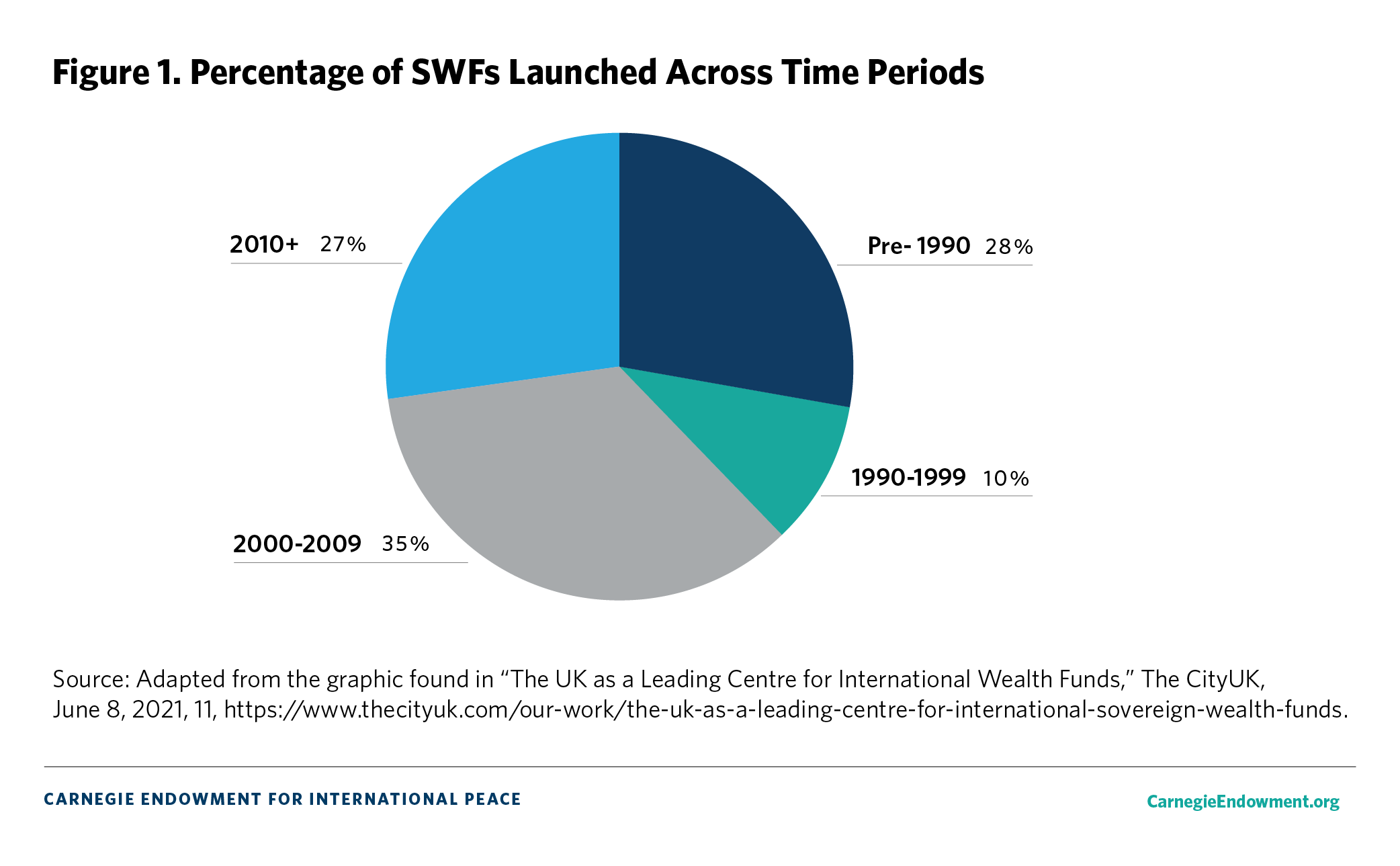

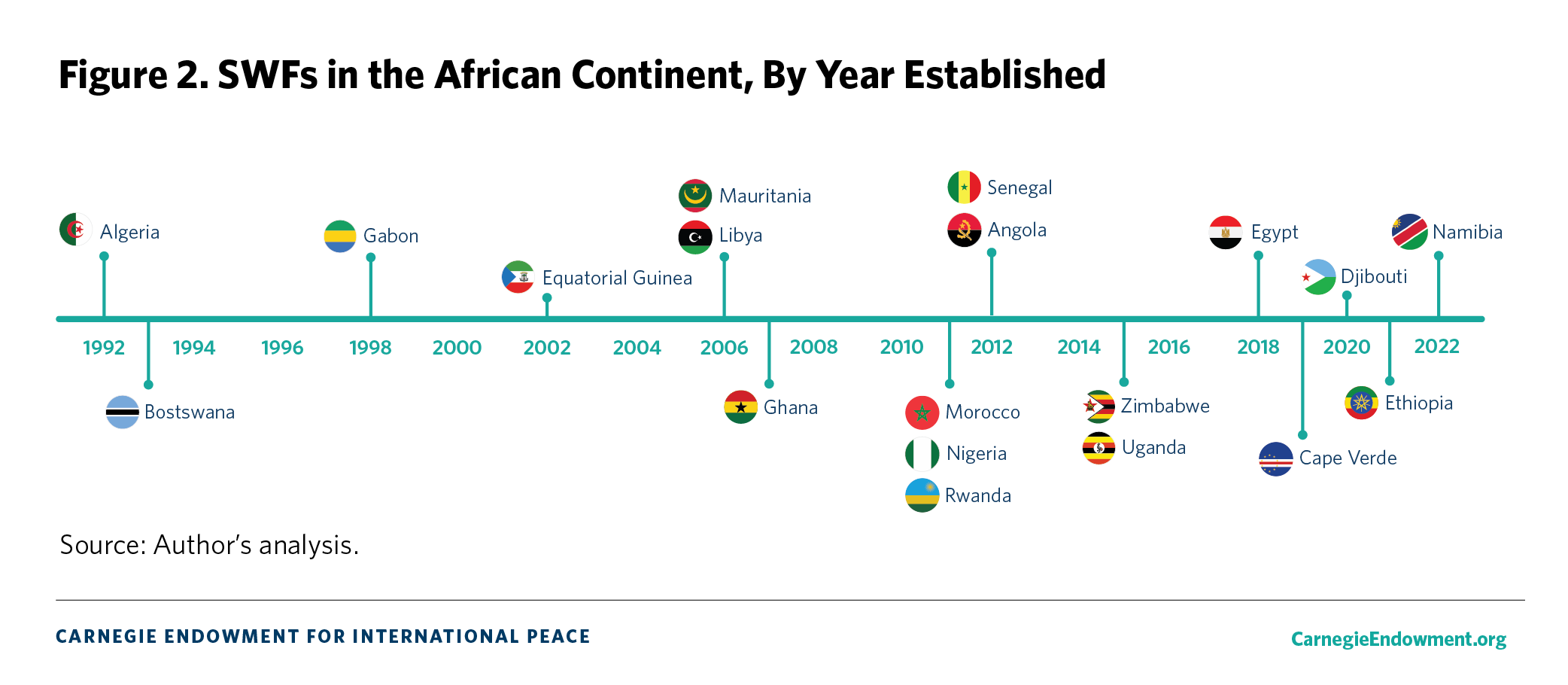

Charting the story of SWF growth provides important evidence for why so many SWFs appear to have serious corruption, money laundering, and other governance risks. Globally, prior to 2010, there were only fifty-eight SWFs.14 Today, however, SWFs have become an increasingly “fashionable” type of state-owned entity (see figure 1), and there are currently 118 operating or prospective SWFs.15 In the African continent alone, prior to 2000, there were only two SWFs. Since 2000, sixteen new SWFs have been set up (see figure 2). This increase in the number of SWFs has also meant a dramatic increase in the value of the assets that they own or control.

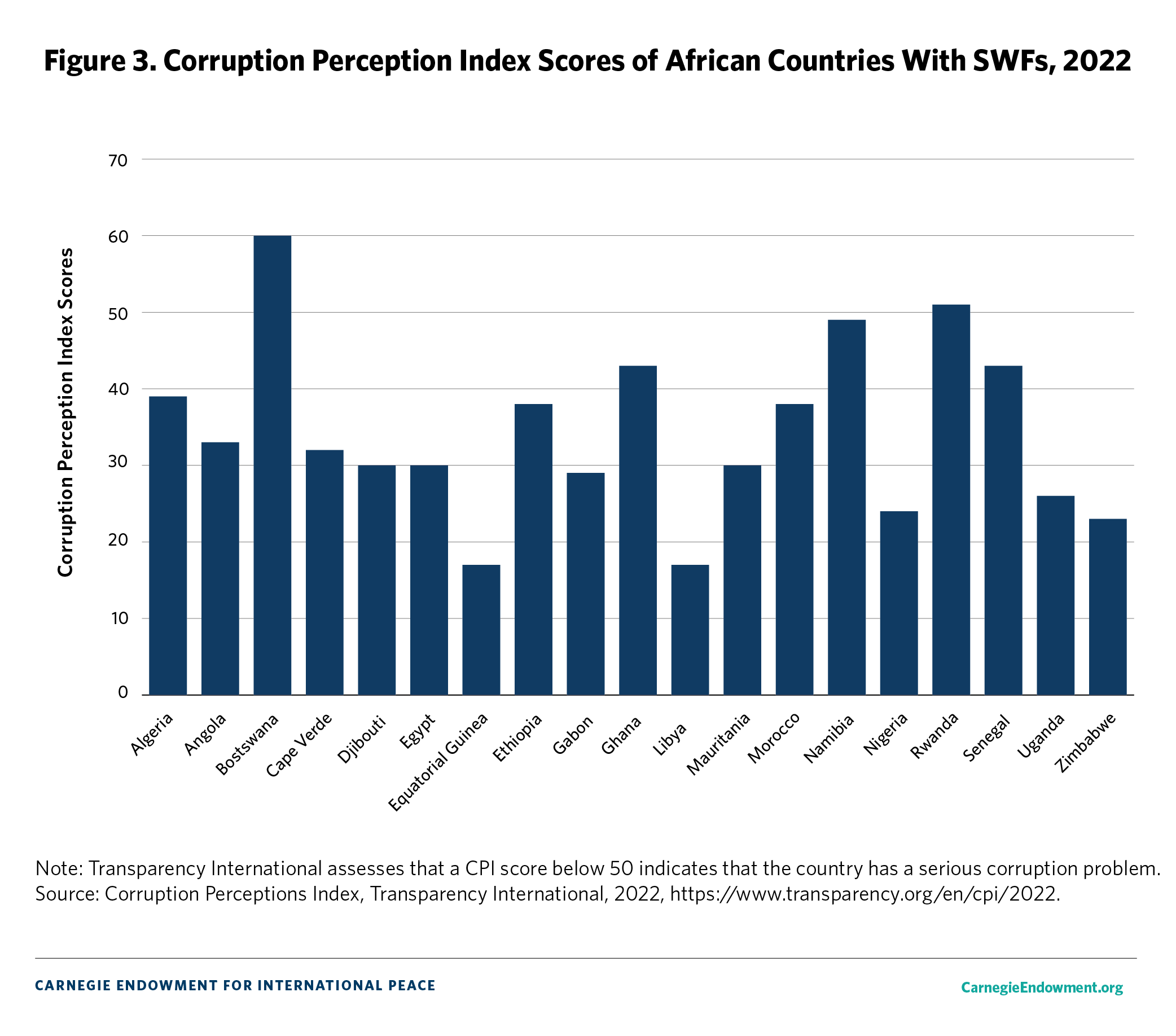

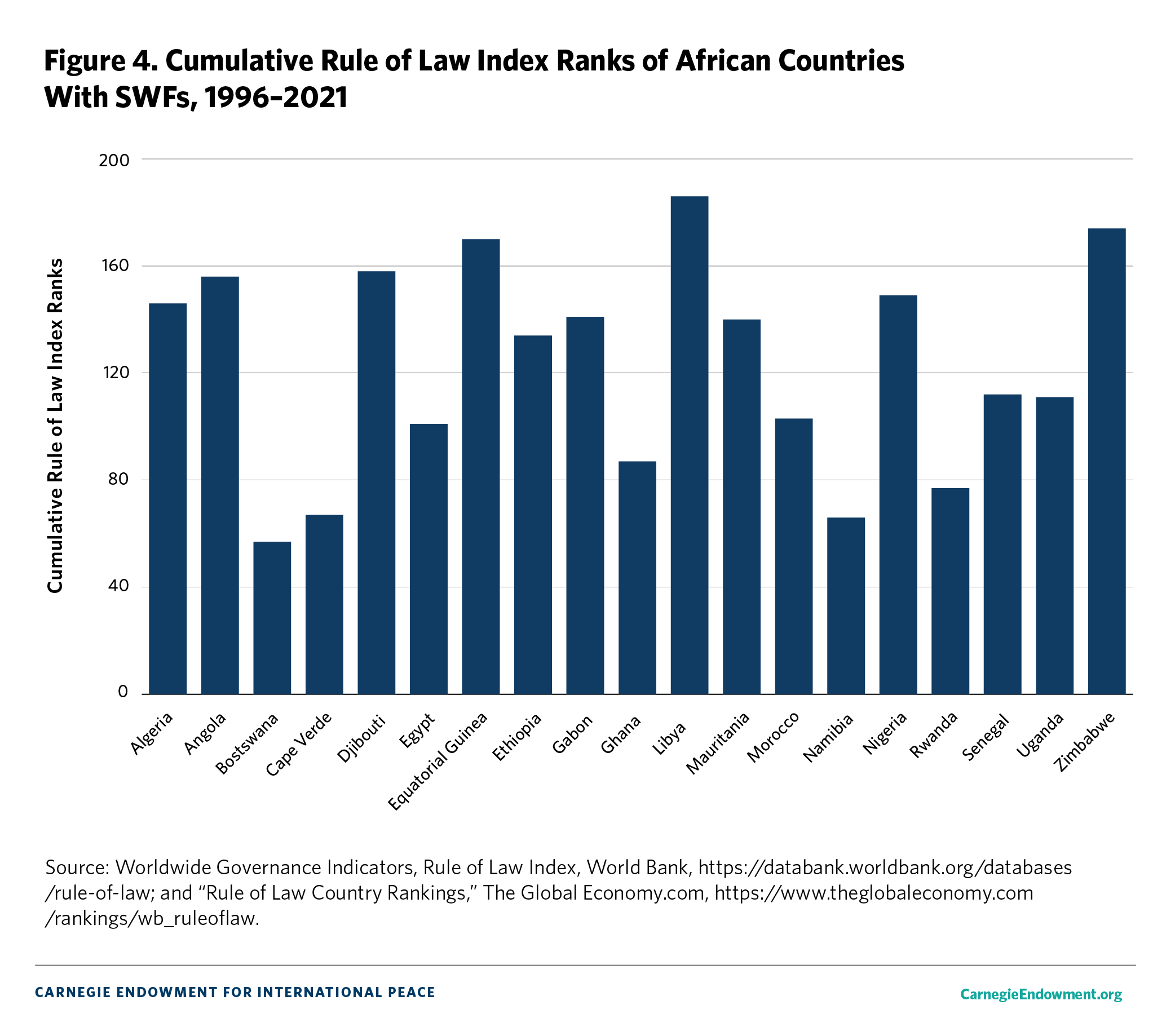

This dramatic growth in SWFs is concerning because they have been established not just in countries with strong rule of law and civil liberty protections but also in countries marked by high corruption risks, insecurity, violence, and weak or absent rule of law. For example, in 1999, the State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan was set up, and as of April 2023, it reportedly had $53.4 billion in AUM.16 Meanwhile, in 2022, Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) gave Azerbaijan a failing score of 23 out of 100, ranking the country 157 out of 180 countries; in 2021, the World Bank’s Rule of Law Index (ROLI) ranked the country 131 out of 192 countries.17 In another example, in 2002, Equatorial Guinea’s Fund for Future Generations was set up (see chapter 4), and now it reportedly has $165 million in AUM.18 Yet the CPI gave Equatorial Guinea a failing score of 17 out of 100, ranking the country 171 out of 180 countries; the ROLI ranked the country 175 out of 192 countries.19 Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate the CPI and ROLI index scores of African countries where SWFs have been established.20 With few exceptions, like Botswana and Namibia, the vast majority of countries on the continent that have or plan to set up SWFs have significant corruption risks and weak rule of law systems. Can SWFs that are meant to safeguard wealth for future generations successfully operate in a corruption-rich environment? The evidence that unfolds in the following chapters raises serious concerns about the state of play of existing governance norms and enforcement efforts. It also provides a compelling narrative on the need for clear policies related to the management of SWFs and lends weight to the recommendations included at the end of this compilation.

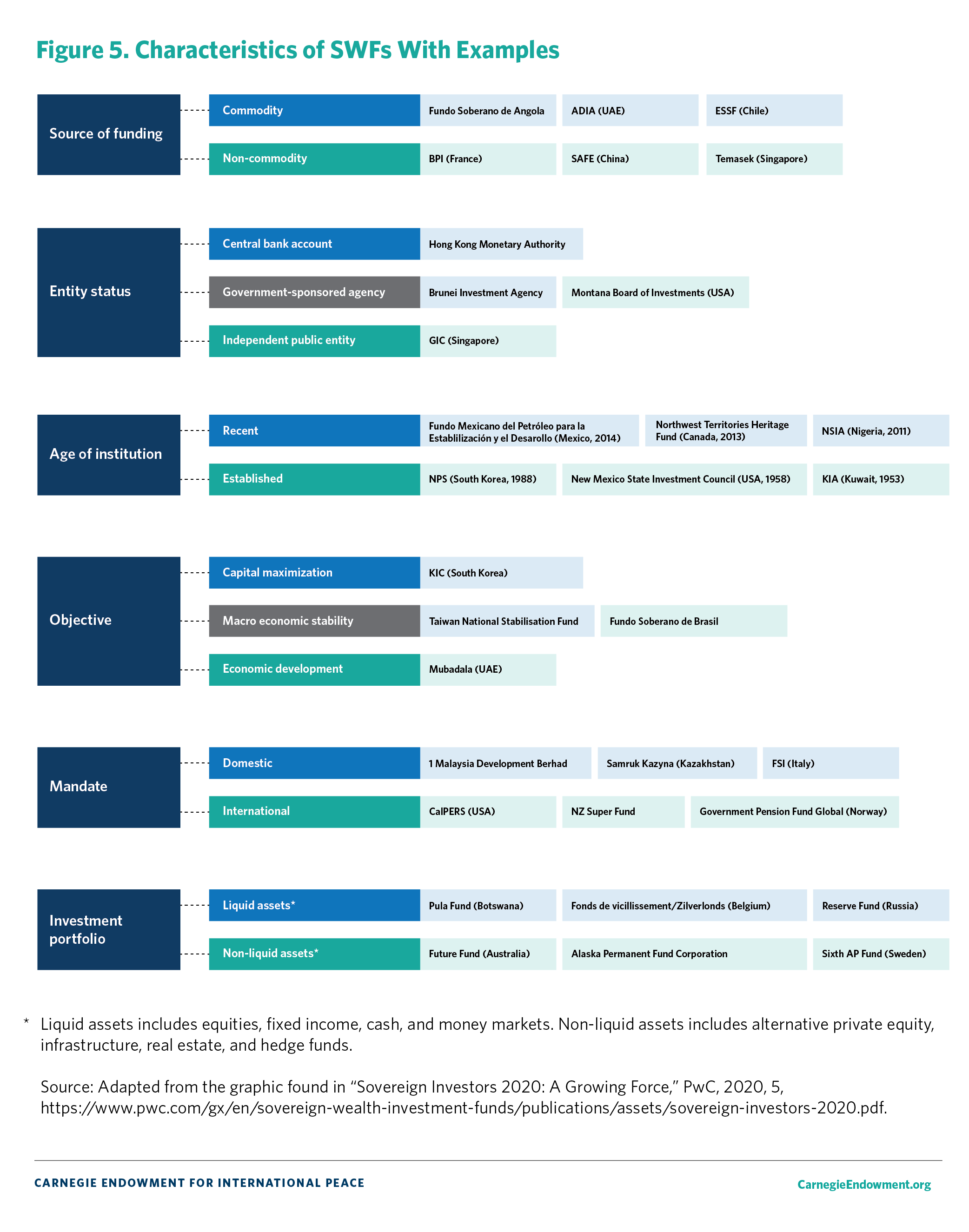

This dramatic growth in SWFs is also concerning because the sources of funding, objectives, mandates, investment portfolios, and the legal mechanisms through which SWFs have been set up vary significantly, making it more difficult to monitor and assess SWF behavior. Early SWFs could be broadly divided into three categories based on their unique objectives: (1) stabilization funds established to insulate a country’s economy from both internal and external shocks; (2) capital maximization funds established to transform natural resource revenues into longer-term wealth for future generations; and (3) strategic development funds established to help create jobs, improve infrastructure and development within the country, and ultimately help diversify the economy by moving it away from reliance on a particular sector or natural resource. Today, SWFs often have multiple objectives and mandates, and governments can alter the objectives based on changing priorities.

For instance, the KIA was set up in 1953 with the objective to invest Kuwait’s excess oil revenues and preserve the country’s oil wealth for future generations, and its mission has not changed.21 Similar to the KIA, the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund of Kiribati was created in 1956 to act as a store of wealth for the country’s earnings from phosphate mining.22 Early funds of this type were conservative in their investment strategies, primarily focused on investing in a mix of money market instruments.23

However, later SWFs—such as Bpifrance, Singapore’s GIC, the Türkiye Wealth Fund, and the Maltese National Development and Social Fund—were set up as noncommodity funds financed through the respective country’s foreign reserves or as existing public equity interests or assets financed through the sale of state-owned assets (or in Malta’s case, through the sale of the country’s passports).24 As the sources of funding have changed, so have the investments, objectives, and mandates of the funds.

According to the case studies in this compilation, SWFs have been used to amass large art collections (see chapter 3); acquire global sports teams and sponsor international sporting events (chapter 4); fund the development of, and manage the profits from, a national COVID-19 vaccine program (chapter 7); and route payments for defense contracts (chapter 11). All these investments are supposed to further the SWF’s stated goals of capital maximization, macroeconomic stability, or economic development. However, in reality, they are commonly linked to an array of potentially unlawful activities. And as each of the case studies in this compilation highlight, one need not probe far to reveal a pattern of troubling behavior. But, as this compilation will also lay out, domestic and international standards lack the language necessary to identify risks that lead to this behavior. Additionally, the discussion around SWF risks is seemingly divorced from the wider discourse on anti-corruption, anti–money laundering, and other norms associated with other types of state-owned entities.

Figure 5 illustrates that SWFs exist across a range of categories. Coupled with the aforementioned definitional issue, these variations in type make identifying atypical SWF behavior or SWFs at risk for corruption and money laundering all the more challenging.

In addition to the aforementioned factors, how an SWF’s objectives are fulfilled can contribute to governance and illicit finance risks. The mechanics of these investments and the network of actors and jurisdictions that facilitate these investments provide additional context on why corruption and broader governance risks of SWFs are allowed to thrive. As complex investment vehicles, SWFs and their investment strategies can be mapped in myriad ways; however, because the intention of this compilation is to address the corruption and money laundering pathways of SWFs, this paper will focus on answering three questions: How do SWFs invest? Who helps SWFs invest? And where do SWFs invest?

How Do SWFs Invest?

The purpose and objective of a fund determine how its investments are directed. For instance, capital maximization funds like the KIA—which tend to be the most “risk-seeking”—invest in hedge funds, real estate, private equity, and infrastructure (known collectively as “alternatives”) and other so-called yield-generating assets to meet their objectives. These assets aim to bring an investor short-to-medium-term returns by paying out dividends, providing an interest, or generating similar financial income.

Stabilization funds like the Mexico Oil Revenues Stabilization Fund have short investment time horizons and tend to be very liquid. As a result, they are looking for investment opportunities, such as bonds, treasury bills, and guaranteed investment certificates, otherwise known as long-term fixed income securities.25 Finally, sitting in the middle, economic development funds like Mubadala in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) invest in alternatives and other safer assets—such as short-term fixed income securities—to ensure a stable stream of lower-risk financing and to provide the SWF with consistent returns (see figure 5).26

These neat demarcations are useful in categorizing the overall mode of operations of SWFs, but they do not reflect all the ways in which a country uses an SWF or how the SWF’s priorities can shift over time.27 Stabilization funds, which tend to be the most risk averse, invest their money in cash, shares listed on a stock exchange, or investments that will provide a fixed income to the SWF through the life cycle of the investment.

For instance, the Malaysian 1MDB fund was set up as an economic development fund, and its investments were apparently intended to further the country’s development goals. But as chapter 3 discusses, these investments were merely a front to divert $4.5 billion with the assistance of numerous individuals, including government officials from Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The investment mechanism was seemingly legitimate—involving financial institutions with world-class reputations, such as Goldman Sachs—but, in reality, it was laundering stolen money to fund the individuals’ lavish lifestyles.

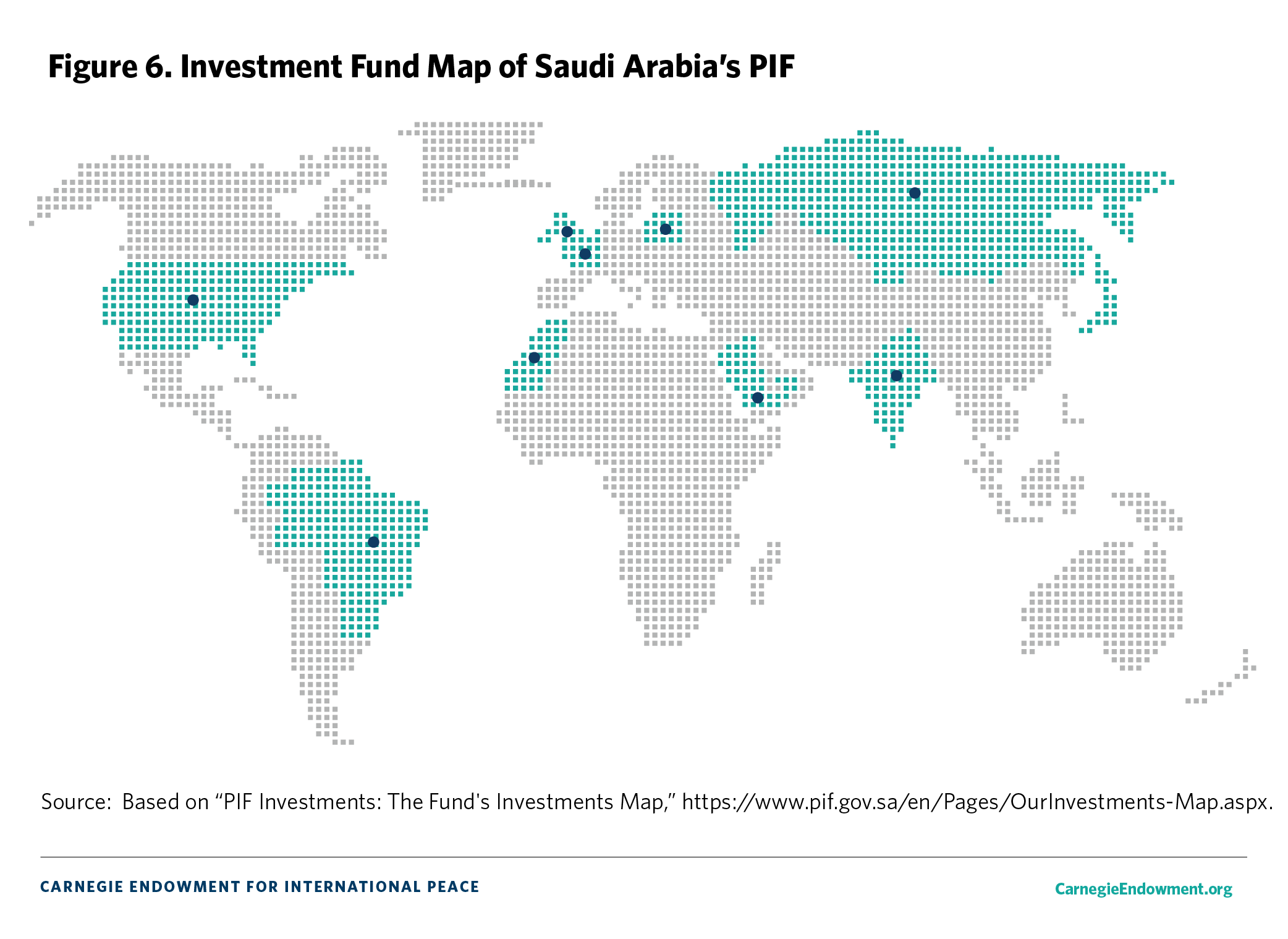

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has a similar global footprint and now supposedly has about $700 billion in AUM (see chapter 6 and figure 6).28 However, officials within the PIF have reportedly voiced concerns about the riskiness of PIF’s $2 billion investment into Affinity Partners, a private equity fund owned and operated by Jared Kushner.29 Investments like this and the recent pact between Saudi Arabia’s LIV golf tournament with the Professional Golf Association (PGA) Tour blur the line between pursuing economic development and purchasing economic or political influence, thus making assessments around corruption and other governance risks more challenging.

The way these SWF investments are carried out presents another difficulty in tracking them. SWF investment methods broadly fall into three types:

- Indirect SWF investment (the most traditional method), in which the SWF provides capital to another investment fund and allows that fund to manage the SWF’s money.30 This method accounted for the bulk of SWF activity in 2020 and 33 percent of all SWF allocations.31

- Direct SWF investment, such as the Qatar Investment Authority’s (QIA) purchase of the French soccer club Paris Saint-Germain in 2011–2012.32

- SWF and partner co-investment, such as the complicated 2016 deal between QIA and the commodity trading firm Glencore to invest in Russian oil giant Rosneft.33

Each investment method has an impact on profitability and its own corruption, money laundering, and governance risks. On the face of it, direct SWF investment may appear the easiest to track and therefore the easiest for public oversight and for authorities to check for money laundering or corruption risks. However, financial institutions and government agencies still need to explicitly evaluate and differentiate these risks based on the SWF’s location and the governance and transparency levels within the fund. With much of the discourse focused on the national security risks of SWFs, there appears to be little scrutiny of a variety of other types of risks. For instance, a lawsuit filed in Massachusetts alleges that $3.5 billion was stolen from the Saudi PIF and some of it was used to purchase eight condos in Boston.34 Yet prior to the lawsuit filed by the Saudi government, the transaction did not raise any red flags from financial institutions within the United States.

Still, indirect SWF investment may be more challenging to track and monitor. SWFs can often invest in a private equity fund and then use the private equity fund to make further purchases. This obscures the SWF’s identity and creates corruption, money laundering, and national security risks. For instance, a 2018 report from the U.S. Department of Defense stated that through such investment strategies, the Chinese government has been able to gain access to numerous cutting-edge, sensitive technologies from U.S. companies, which the department called “the crown jewels of U.S. innovation.”35 Similarly, another report from leading anti-corruption and financial transparency advocacy groups highlighted how municipal governments in China funded numerous Chinese venture capital firms that were then able to invest in sensitive U.S. technology sectors without drawing attention to their government connections.36

Finally, SWF and partner co-investment may present even more of a challenge. The deal in 2016 between the QIA and Glencore helped the two institutions together secure a 19.5 percent stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft for $11.3 billion.37 This investment was designed to give Russia a much-needed cash infusion in response to U.S. and European sanctions on Russia following its 2014 invasion of Crimea, which left the Russian economy and national budget struggling.38 The deal explicitly allowed Rosneft to repurchase the shares and allowed Glencore to purchase 220,000 barrels of oil a day from Rosneft; furthermore, the deal was primarily financed through Russian banks due to the ongoing U.S. and European sanctions.39 In 2017, Glencore and Rosneft sold 14.16 percent of the shares to China’s CEFC energy conglomerate. At the time, the Jamestown Foundation, a leading defense policy think tank, posited that this complex structuring would give China the opportunity to extend its influence over Rosneft, obtain a reliable oil supply that could not be “interdicted by foreign maritime powers,” and strengthen the credibility of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).40

The foundation also argued that the deal would give China “a functional (and opaque) way to essentially ‘bribe’ high-level Russian officials with cash that Moscow desperately needs.” Regarding Russia, it further stated that the deal would allow Rosneft, which has close to ties to Putin, to create “shady privatization schemes and what essentially amounts to a sophisticated version of money laundering via VTB.”41 Additionally, it said that the deal would allow Russia and President Vladimir Putin to create close relationships with “opaque business entities that enjoy state support in the Gulf and China.”

Who Helps SWFs Invest?

SWFs require an army of people to help guide and inform their investment strategies. For example, Norway’s Government Pension Fund–Global, one of the world’s largest SWFs, has a direct staff of more than 500 people from thirty-five countries and operates out of offices in Oslo, London, New York, Singapore, and Shanghai.42 Other smaller or less experienced SWFs may appoint an external investment manager. The chain of actors that help SWFs make investment decisions include the staff of the SWF, financial institutions, various private equity funds, consultants that provide expertise on sector-specific investments, external fund managers, and various other intermediaries vying for a lucrative piece of the SWF pie.

Many worrying patterns of behavior that repeatedly emerge when examining instances of SWF malfeasance and corruption come from weak governance norms that surround these external relationships, such as when private sector entities are either looking to gain the SWF as a client or are responsible for managing the SWF’s investment portfolio. In reading this compilation, the problematic nature of these relationships quickly becomes evident. In the case of the Angolan SWF (see chapter 4), the fund’s asset manager, Jean-Claude Bastos de Morais, advised the SWF to invest in at least four different opportunities where Bastos himself held an interest.43 In another case, the French bank Société Générale agreed to a settlement of 963 million euros ($1.05 billion) with the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) for allegedly bribing Libyan officials for the chance to manage the LIA’s investments.44

The case studies in this compilation demonstrate that a troubling relationship can exist between corrupt political regimes and private sector institutions that seek to maximize profit or personal gain but may give little consideration to what happens to citizens if the SWF’s resources are lost. However, all of this is not to suggest that external advisers should be disallowed; rather, stronger governance rules both within SWFs and private sector entities are necessary for SWFs to actually benefit from robust, external financial sector expertise.

Where Do They Invest?

The illicit finance and governance risks within SWFs do not exist in a silo. Almost always, SWFs invest outside their home country. Therefore, understanding where SWFs invest can be valuable in determining how best to address potential governance risks, including risks of corruption and money laundering. A 2021 analysis of a sample of SWF investment patterns found that in 2020–2021, the United States, India, China, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Russia, and Brazil collectively represented the destination for 73 percent of all direct investments. The United States accounted for the largest direct SWF investment at 28.8 percent, followed by India at 14.7 percent and China at 10.5 percent.45

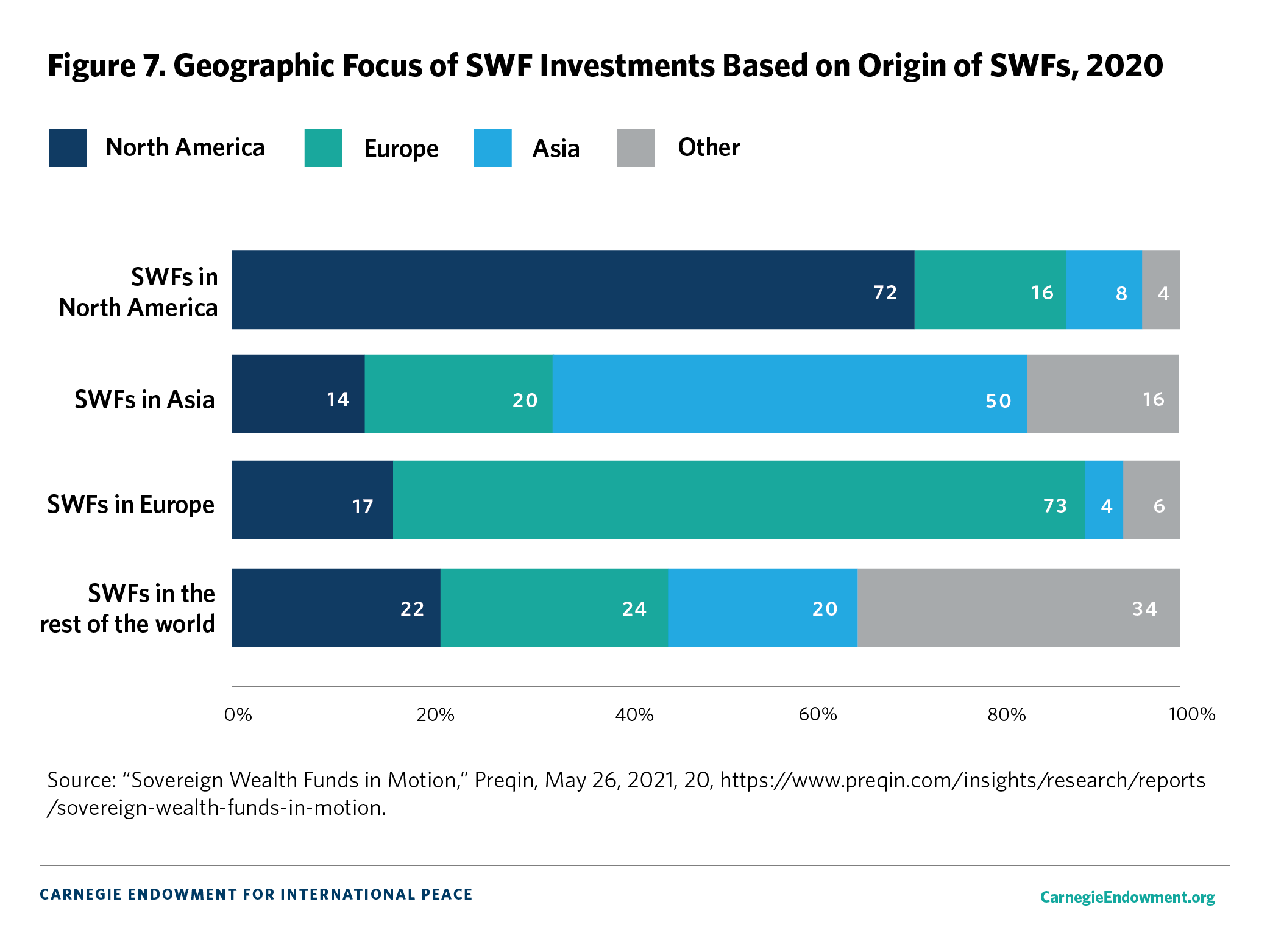

This pattern of investment, however, is only true of direct SWF investments. When including indirect investments, the amount invested in the United States, while significant, is not as large as the investment in the geographic region where the SWF is based. For instance, SWFs based in North America make 72 percent of their investments there, while SWFs in Asia make 50 percent of their investments in Asia and only 14 percent of their investments in North America (see figure 7).

These patterns of investment mean that countries serious about preventing their economies from being used as a conduit or safe haven for the proceeds of corruption and money laundering are in a prime position to scrutinize SWF investments for such risks.

Yet the case studies in this compilation show that despite the corruption, money laundering, and other governance risks associated with this significant pool of capital, SWFs or the legal structures through which SWFs invest appear to face minimal oversight when traversing the international financial system. For instance, as described in chapter 9, there appears to be little scrutiny of the Maltese SWF’s equity and bond investments in the United States as well as in emerging markets, even though that SWF is funded primarily through a controversial citizenship-by-investment program. Likewise, the 1MDB fund discussed in chapter 3 was able to invest in real estate, art, and movies in the United States with minimal scrutiny.

Sovereign Wealth Fund Regulation

Understanding the nature of existing international standards applicable to SWFs provides much-needed context on how corruption, illicit finance, and other governance risks within SWFs have emerged. The International Working Group of SWFs established the Santiago Principles in 2008 as a result of the tension between maintaining open investment policies in developed economies and protecting against the national security risks that SWF investments bring. The goal was to ensure the “domestic and international legitimacy” of SWFs.46 Today, the group’s successor, the International Forum of SWFs (IFSWF), champions the principles that specifically require SWFs to be transparent, accountable, independent, and commercially oriented.47 While laudable, the principles are not binding and only serve as guiding norms for SWF governance. Moreover, they do not acknowledge that many SWFs operate in environments with high corruption risks and weak rule of law, and they therefore fail to provide any guidance on how best to operate an SWF in such environments.48

The OECD has also provided several guidance documents on SWFs.49 However, to date, all of the documents have been designed to help countries where SWFs invest their funds address the national security concerns that first brought SWFs to prominence.50 These documents and those written by other international organizations such as the World Bank conspicuously shy away from using the term “corruption” in matters relating to SWFs. This is in sharp contrast to their guidance documents on state-owned enterprises—which explicitly address the issue of corruption.51

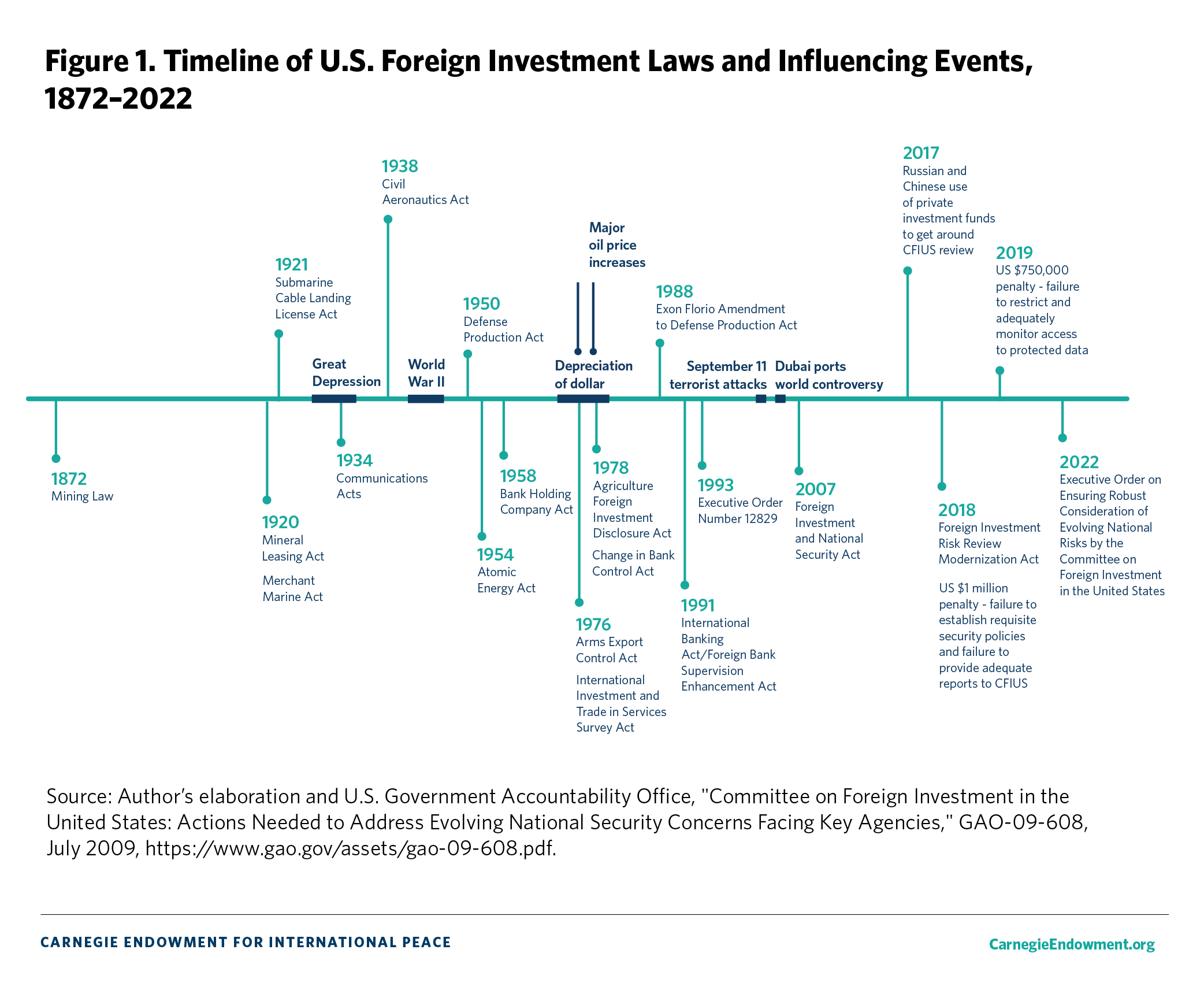

This fixation with national security has trickled down into domestic legislation. Across both the United States and Europe, numerous laws limit or scrutinize SWF investments for potential national or economic security risks but not for corruption and money laundering risks. A 2009 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office laid out the various national security restrictions in place across sectors, including transportation, technology, communications, national security, and energy (including nuclear energy). However, neither the report nor any subsequent public U.S. government agency report has dealt with the danger that SWFs could use the United States as a money laundering conduit or a destination for corrupt funds.52

In the absence of binding international standards, greater transparency through public information disclosure would help ensure accountability and reduce the risks of corruption and other types of illicit finance. This is a model particularly favored by the extractives sector to reduce corruption and associated money laundering risks. In many countries, foreign aid and investment into the extractives sector is contingent on meeting standards set forth by the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative, the Open Contracting Partnership, and other similar efforts.53 However, SWFs have thus far largely succeeded in keeping their operations and investments shrouded in secrecy. Exceptions like Norway’s Government Pension Fund, which has robust transparency and disclosure practices, have not shifted the overall SWF culture toward transparency. Gaps in transparency and data limit the ability of researchers and governments to better capture and track corruption and money laundering in SWFs (see chapters 2 and 12).

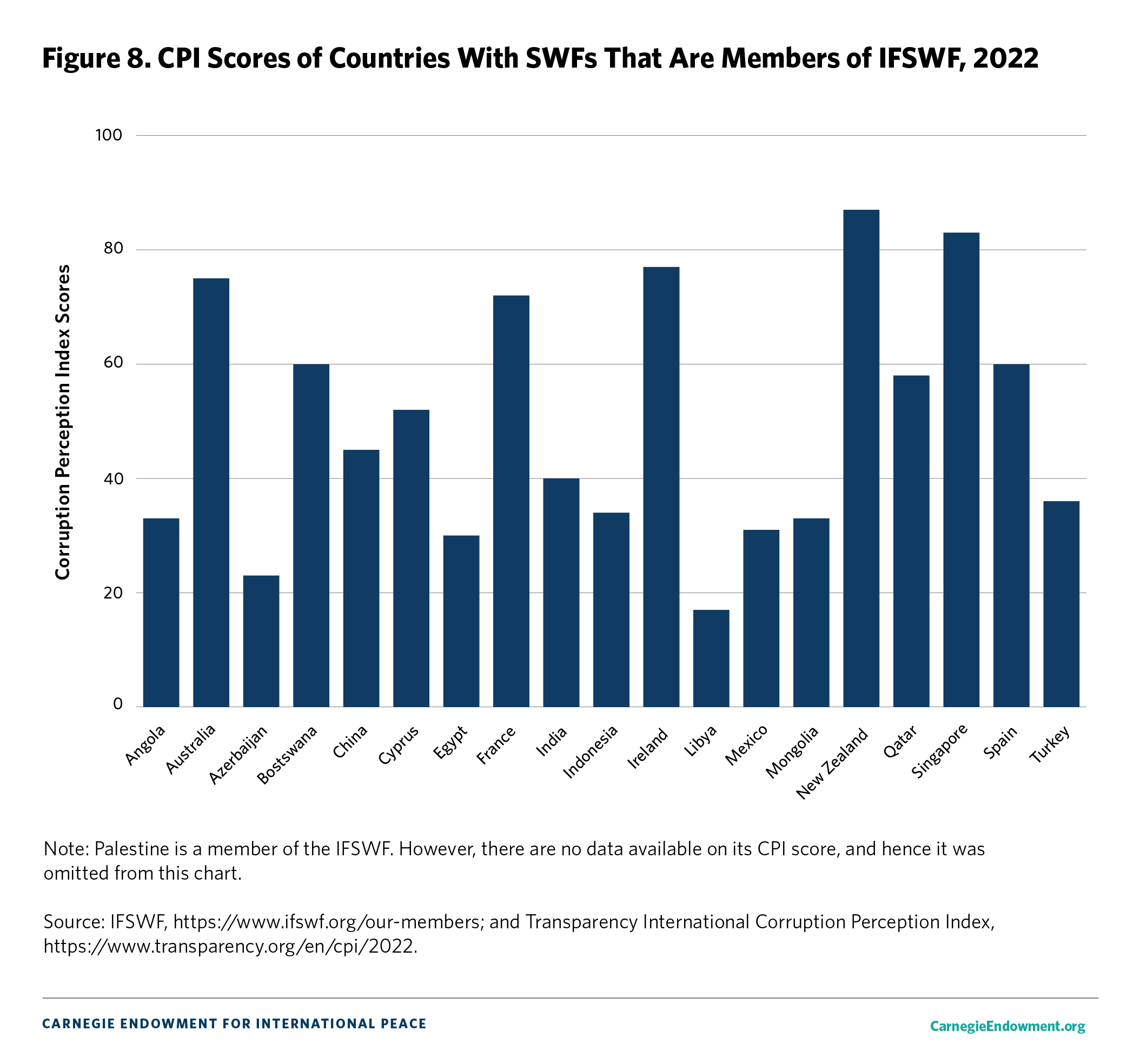

Finally, in the absence of clear regulations, industries often set up self-regulatory bodies to ensure standards and good governance. The IFSWF is the closest organization that exists to fulfilling that role for sovereign wealth funds. The organization was incorporated in 2014 to strengthen the SWF “community through dialogue, research and self-assessment.”54 The IFSWF model permits members to self-assess the robustness of their governance standards. Needless to say, this has not created the necessary incentives for SWFs to critically examine their operations. Several funds mentioned in this report are IFSWF members and have given themselves strong self-assessment scores despite the publication of news stories that raise legitimate concerns about the operations of these funds. An analysis of IFSWF members’ and associate members’ CPI scores reveals that a significant number of SWFs operate in corruption-rich environments (see figure 8). It thus remains an open question whether IFSWF membership provides some of these funds, whose behavior may raise red flags, a reputational benefit and added credibility.

Compilation Overview

Against this backdrop, the eleven chapters in this compilation examine specific cases that demonstrate SWFs’ susceptibility to corruption, money laundering, and other governance issues and the enabling environment that stymies efforts at detection and public oversight.

Chapter 2 further describes the potential corruption risks associated with SWFs, including how the current voluntary standards fall short. It also documents how the lack of free, publicly available data on SWFs prevents oversight and accountability by governments, civil society, and the media. It notes that the opacity of SWFs can lead to fears that funds are being used for political goals or being co-opted, rather than being used for their stated purpose.

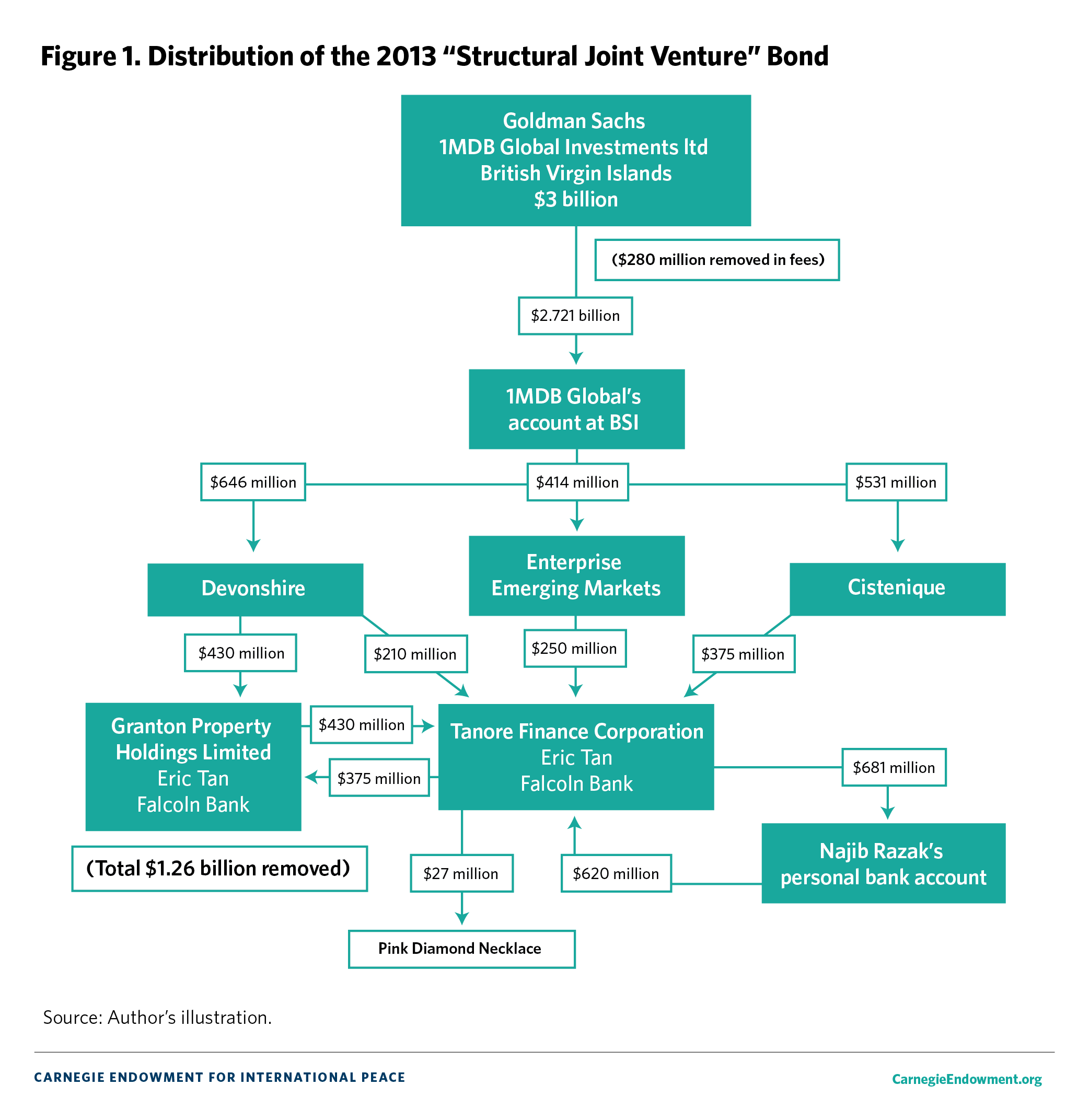

Chapter 3 describes one of the most famous and egregious examples of corruption associated with SWFs: the so-called 1MDB scandal. 1MDB was a sovereign development fund intended to improve the infrastructure and investment environment of Malaysia. Instead, $4.5 billion was siphoned off by senior Malaysian elites, politically connected individuals, and bankers to purchase everything from yachts to art to real estate. This case thus provides a model for how SWF-associated corruption and money laundering schemes can work and how their financial complexity can enable corruption and other malfeasance to continue for years largely undetected.

As noted in this introduction chapter, states have traditionally used SWFs to diversify the proceeds from natural resources and ensure that the proceeds can be saved for future generations. Chapters 4 and 5 highlight potential governance risks associated with natural-resource-based funds. In the case of Angola in chapter 4, a highly autocratic regime used its control over the government to divert oil funds to relatives and friends of the president, even though at the time it was ranked as having relatively good SWF governance by various indices. The Angola case also highlights how reforms can create cleaner and more resilient SWFs.

The case of Equatorial Guinea in chapter 5 then describes how an extreme lack of available information about SWF activity increases the risks that money will be illegally diverted. The well-documented grand corruption associated with the country and the fact that the oil—upon which the country’s export revenue depends—is due to begin to run out within a decade heighten the need for the highest levels of transparency and good governance of the SWF to be instituted in a most timely manner.

Chapter 6 further describes Saudi Arabia’s PIF, one of the world’s largest SWFs. The PIF, and especially its associated Vision 2030 fund, has been used to acquire world-famous sports teams and even establish an entirely new golf franchise through its pact with the PGA, giving Saudi Arabia significant control over the elite-level tournaments associated with an entire sport. Such investments provide a means for authoritarian leaders such as Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to launder their reputations through sports using the proceeds of their country’s natural resources.

Even SWF funds disbursed to help in an emergency like the coronavirus pandemic are not immune from allegations of diversion and corruption. Chapter 7 describes how Russia’s leadership gave the funding for and marketing of Russia’s Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccines to the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), an unusual form of SWF. The chapter describes how the RDIF forced some countries to purchase Sputnik V vaccines through a series of shell companies that eventually raised the price to double what it should have been.55

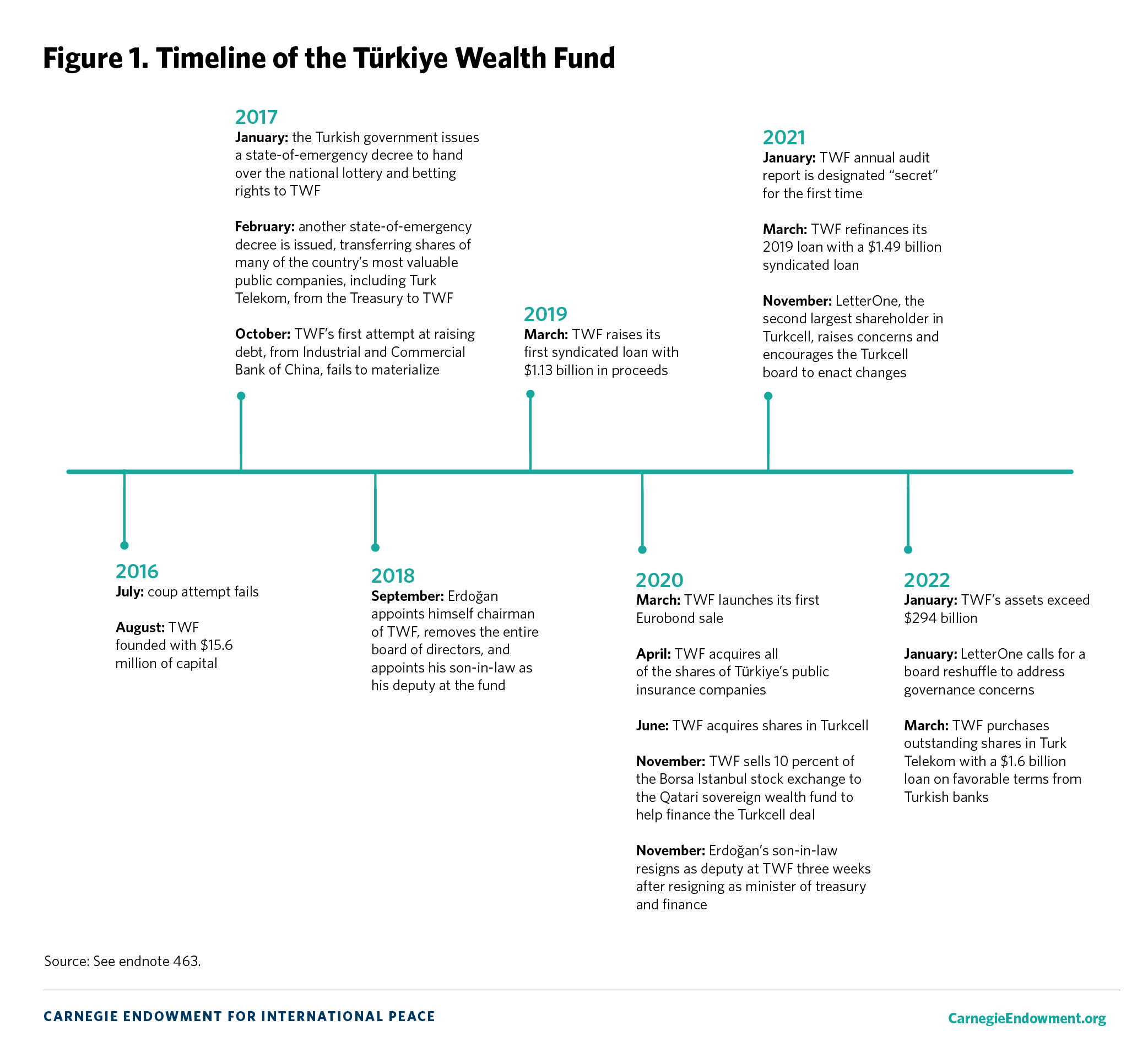

SWFs are usually established to invest and diversify a country’s natural resource wealth, but some countries establish their SWF via loans or taxpayer funds from the state budget instead. This means that such funds can become a parallel budget that is out of reach of oversight by parliaments and citizens, as illustrated by the case of Türkiye’s SWF in chapter 8.

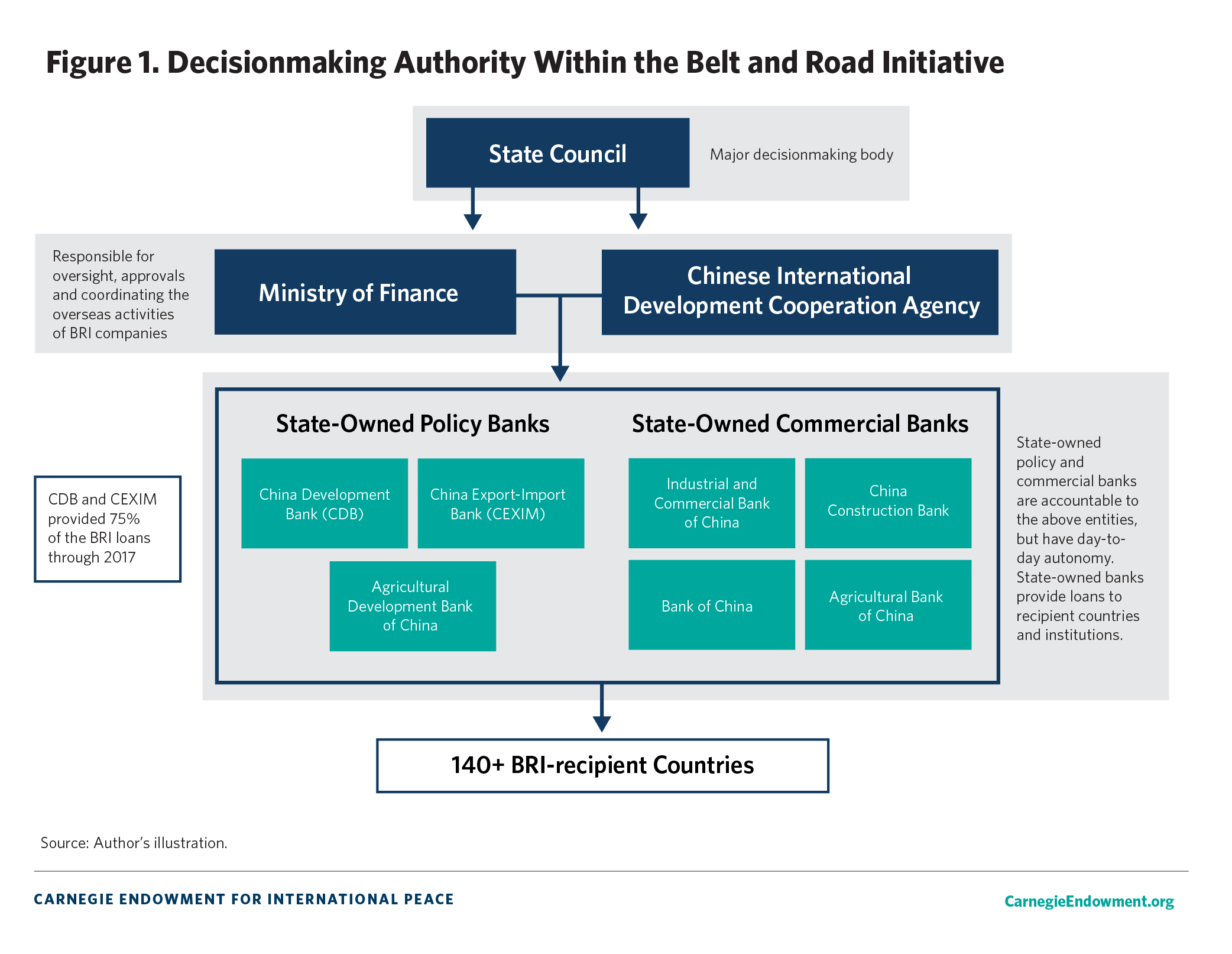

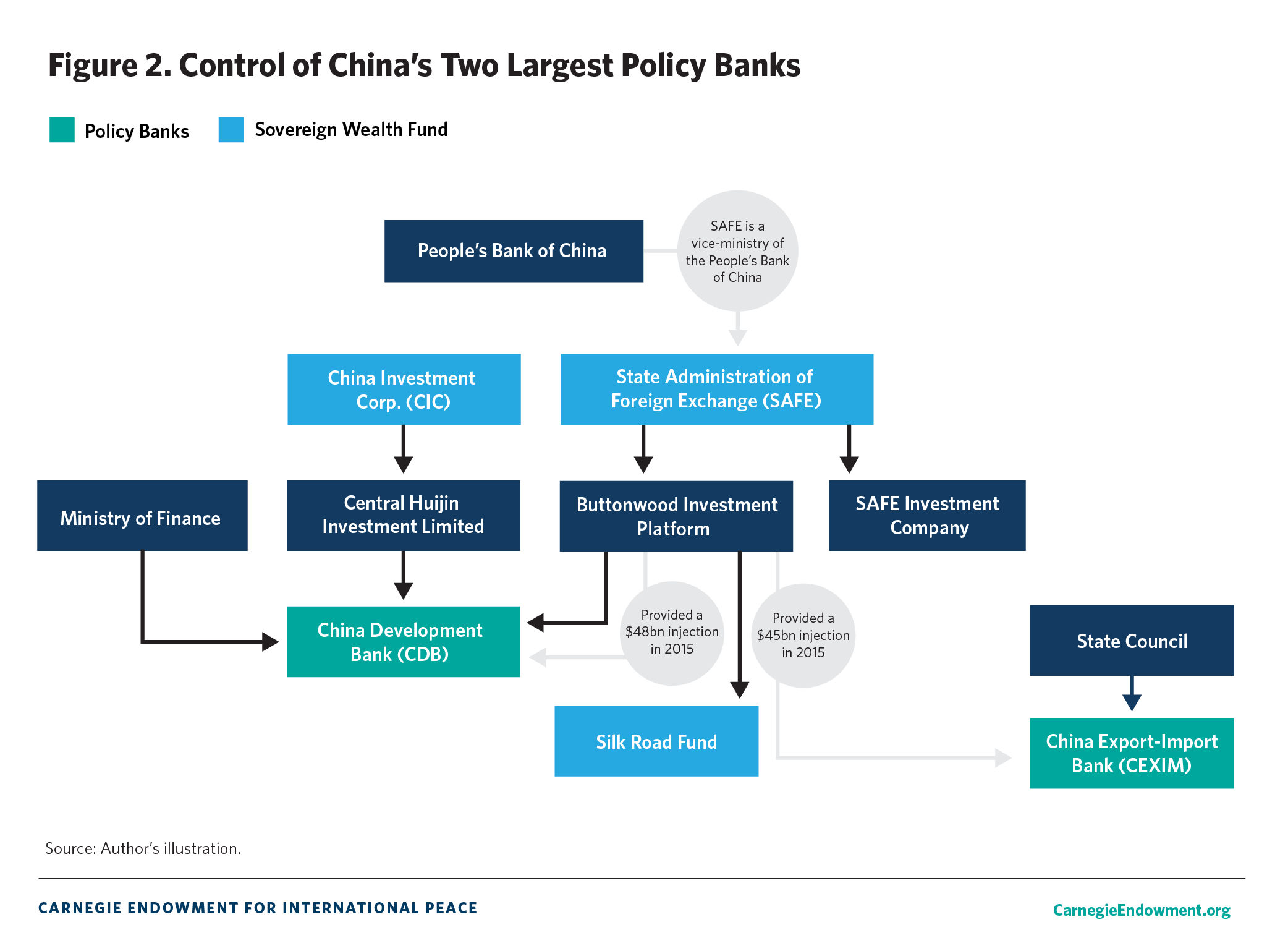

Scholars and policymakers have long worried that China’s BRI is a mechanism for opaque deals designed to help China further its global ambitions, especially through so-called debt-trap diplomacy. Chapter 9 describes how Chinese SWFs undergird the BRI, providing funds to help enable the BRI’s overseas investments.

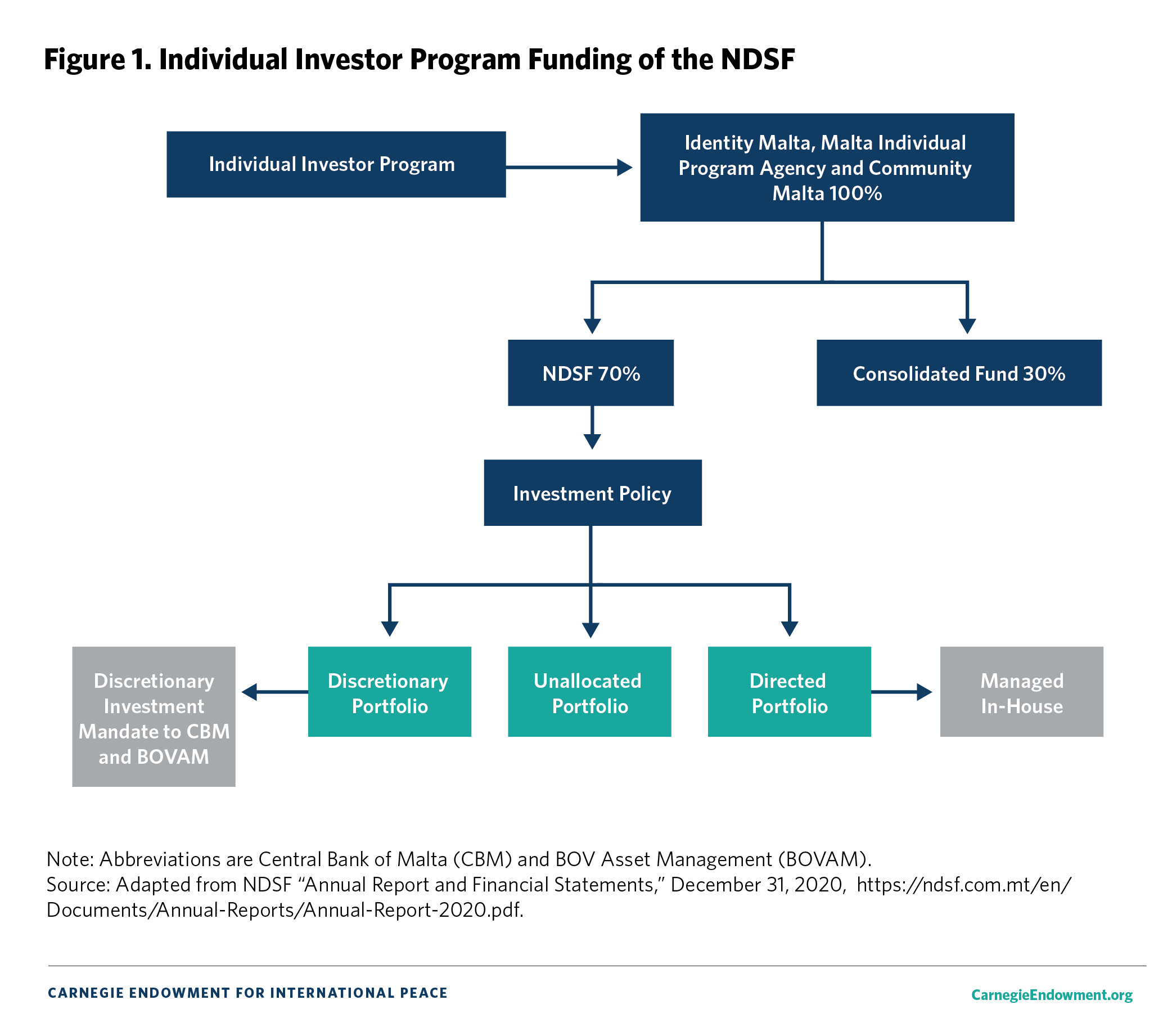

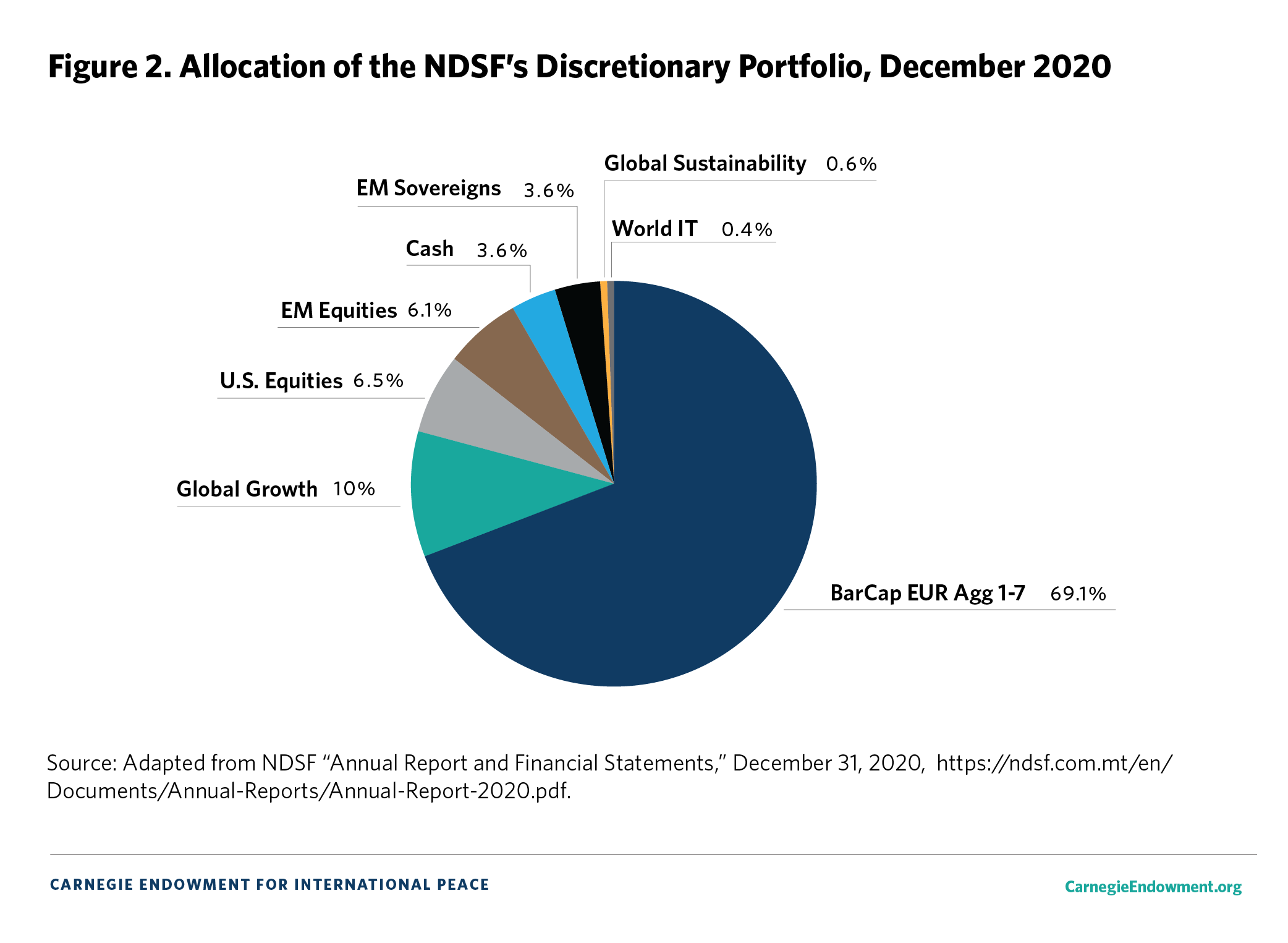

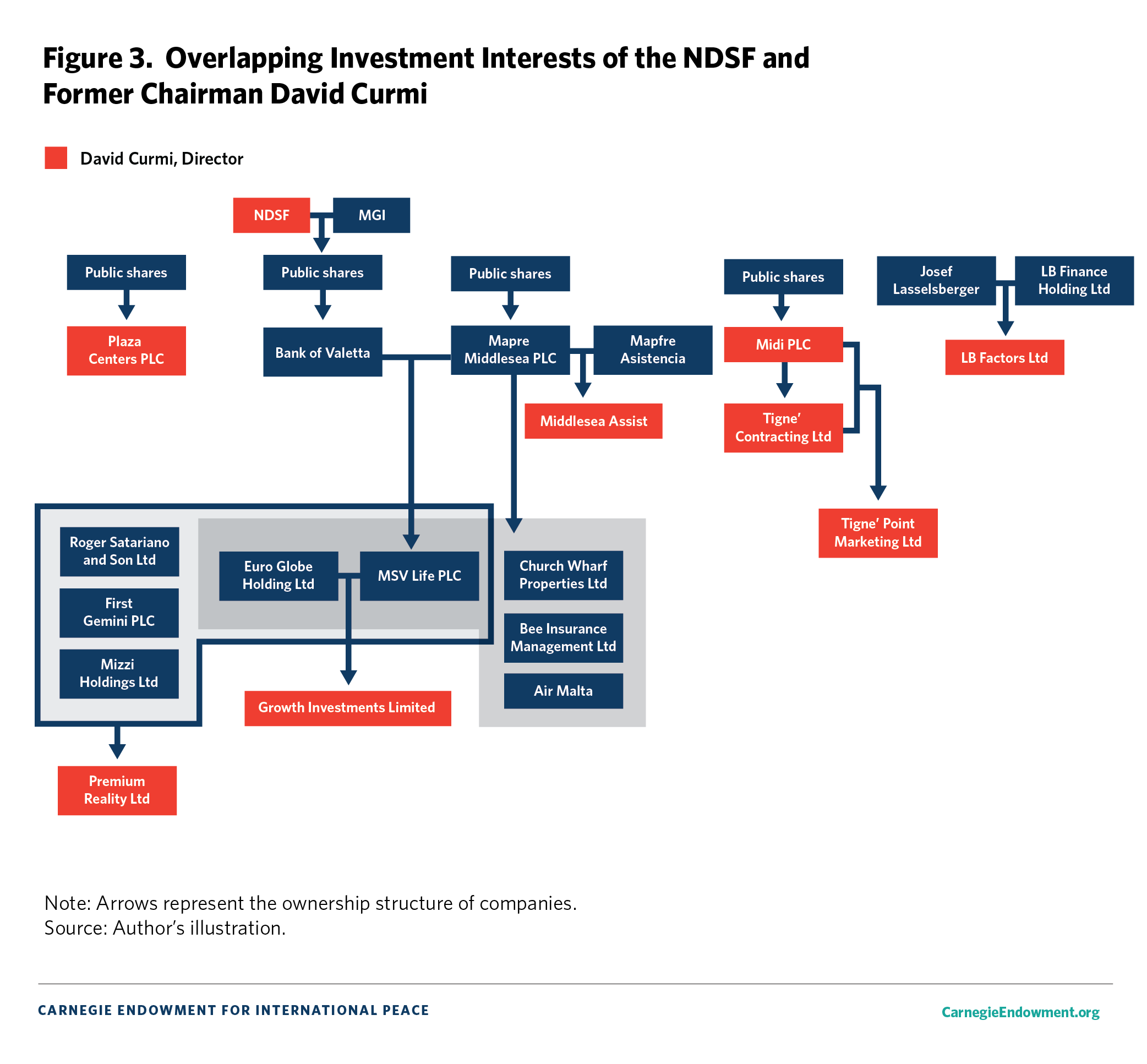

One of the more unusual means of funding a state’s SWF is covered in chapter 10 and features Malta’s SWF. The country uses the proceeds from the sale of Maltese visas and citizenship—so-called golden visas and golden passports—to fund its SWF. Numerous investigations by the European Union (EU) and investigative journalists have documented that this has enabled some corrupt and criminal actors to receive EU residency and/or citizenship and the benefits that go with it. Such funding can create a conflict of interest for Malta because tightening its residency and citizenship requirements could undermine its SWF.

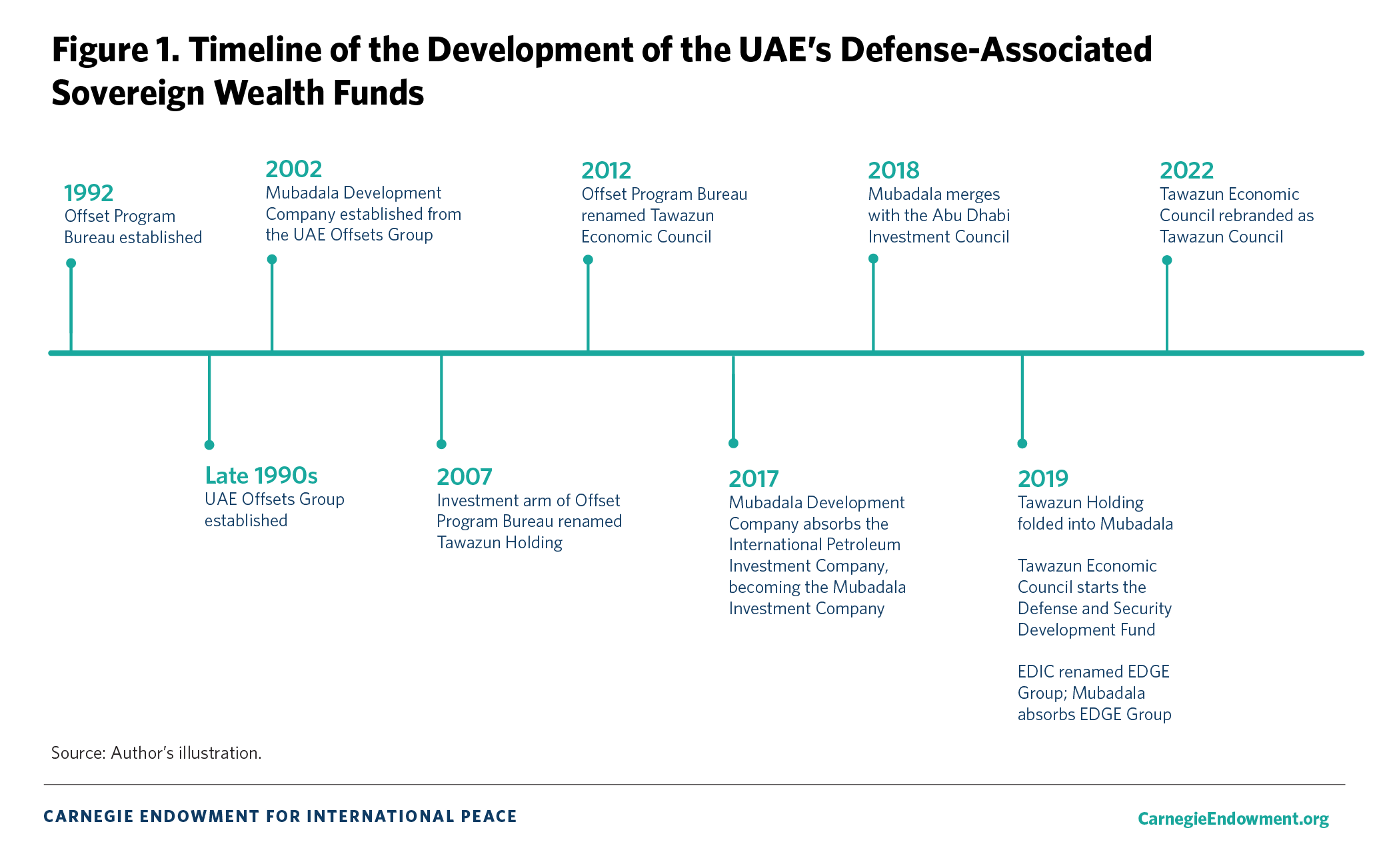

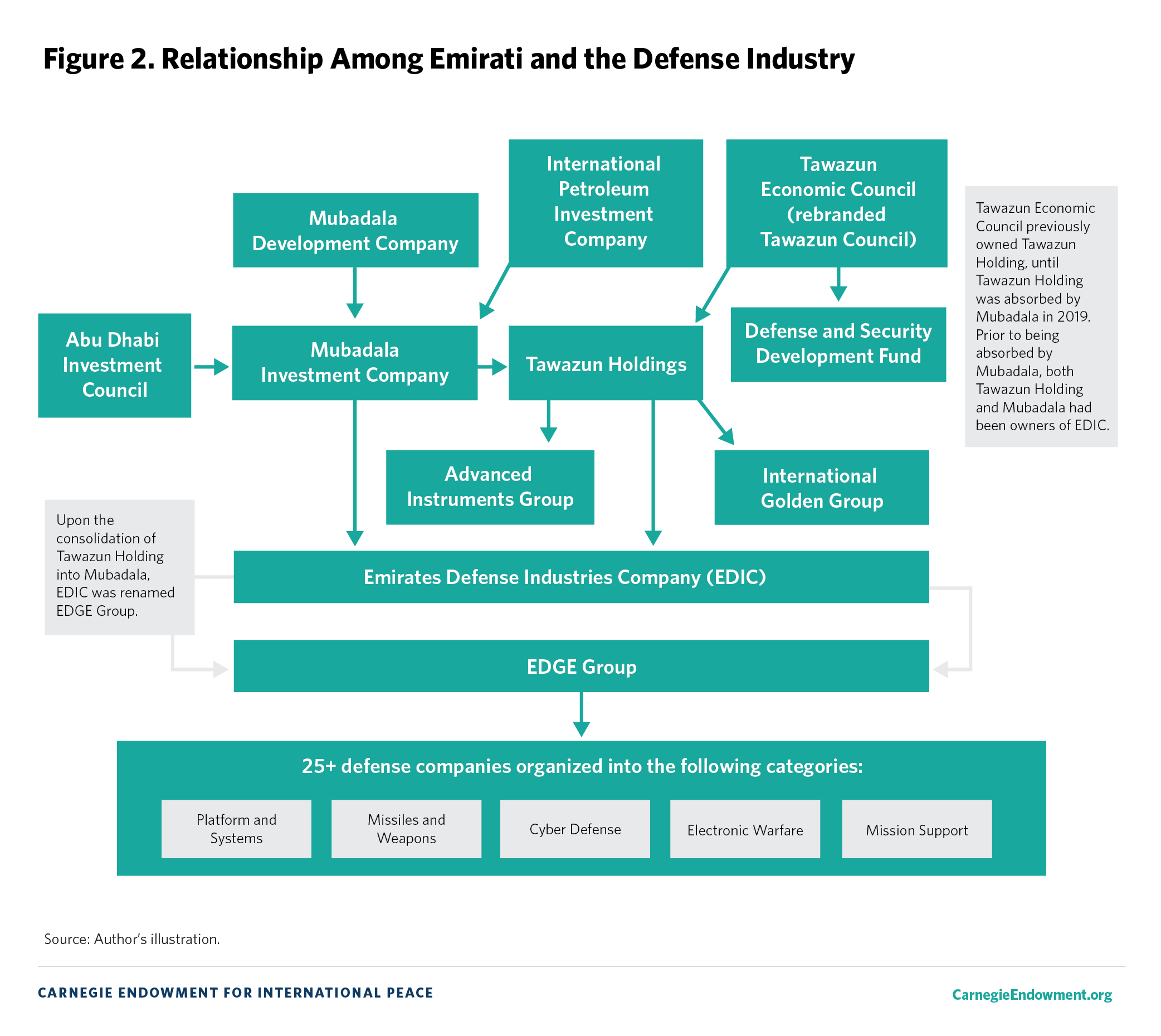

A few countries use the international arms trade to help fund their SWFs, most notably the UAE. One of its most famous SWFs, Mubadala, was founded with money from side contracts for arms purchases from Western defense firms. The arms sector is notoriously fraught with corruption, and the extreme opacity of defense procurement contracts carried out through the veil of sovereign wealth funds makes accountability even more difficult. Because these SWFs are associated with the arms trade, their activities can also have larger ramifications for peace and security, as chapter 11 describes.

Finally, chapter 12 looks at what concrete measures are needed to address the systemic challenges in identifying and responding to corruption, illicit finance, and associated governance risks associated with SWFs. The chapter examines in greater detail the ongoing accountability mechanisms designed to improve SWF governance in their countries of origin, the current legal framework in investment destinations, and what more can be done to make these legal environments meaningful and robust. It also documents what greater transparency among SWFs could mean for both internal and external accountability and, finally, explores whether SWFs should be subject to international evaluations on anti–money laundering, similar to how many other aspects of the financial system are.

Notes

1 Udaibir S. Das, Adnan Mazarei, and Han van der Hoorn (eds.), “Economics of Sovereign Wealth Funds: Issues for Policymakers,” International Monetary Fund, 2010, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/nft/books/2010/swfext.pdf.

2 The concern was that SWFs were becoming security threats by looking to advance their home country’s political goals rather than seeking to maximize their profits. See inter alia Mark A. Clodfelter and Francesca M. S. Guerrero, "National Security and Foreign Government Ownership Restrictions on Foreign Investment: Predictability for Investors at the National Level,” in Sovereign Investment: Concerns and Policy Reactions, eds. Karl P. Sauvant, Lisa E. Sachs, and Wouter P.F. Schmit Jongbloed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Alan P. Larson, David N. Fagan, Alexander A. Berengaut, and Mark E. Plotkin, “Lessons From CFIUS for National Security Reviews of Foreign Investment,” in Sovereign Investment: Concerns and Policy Reactions, eds. Karl P. Sauvant, Lisa E. Sachs, and Wouter P.F. Schmit Jongbloed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Fabio Bassan, The Law of Sovereign Wealth Funds (Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011); and Angela Cummine, Citizens' Wealth: Why (and How) Sovereign Wealth Funds Should Be Managed by the People for the People (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 3–5. Interestingly, earlier incidences where national security concerns were raised often resulted from state-owned enterprise investments rather than SWF investments (for example, the Dubai Ports controversy).

3 Simon Johnson, “The Rise of Sovereign Wealth Funds,” International Monetary Fund, September 2007, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2007/09/pdf/straight.pdf.

4 “Sovereign Wealth Funds in Motion,” Preqin, May 26, 2021, 9, https://www.preqin.com/insights/research/reports/sovereign-wealth-funds-in-motion; and Claire Milhench, “Global Sovereign Fund Assets Jump to $7.45 Trillion: Preqin,” Reuters, April 12, 2018,

5 Prequin and IFSWF self-assesment reports accessed by the author.

6 “Sovereign Wealth Funds: Publically Available Data on Sizes and Investments for Some Funds Are Limited,” United States Government Accountability Office, October 6, 2008, 44, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-08-946. It notes that “[i]n 2007 and early 2008, SWFs, in conjunction with other investors, supplied almost $43 billion of capital to major financial firms in the United States. Citigroup was the major recipient of capital, receiving $20 billion in late 2007 and early 2008. The other recipients were Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, the Blackstone Group, and the Carlyle Group.”

7 Thomas A. Hemphill, “Sovereign Wealth Funds: National Security Risks in a Global Free Trade Environment,” Thunderbird International Business Review 51, no. 6 (2009): 551–566, https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/64327/20299_ftp.pdf?sequence=1.

8 “Explainer: Malaysia's Ex-PM Najib and the Multi-billion Dollar 1MDB Scandal,” Reuters, August 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysias-ex-pm-najib-multi-billion-dollar-1mdb-scandal-2022-08-23.

9 Long before the KIA was established, individual U.S. states had set up precursors to today’s SWFs. Texas set up the Texas Permanent School Fund in 1854; see Texas Education Agency, “Texas Permanent School Fund,” https://tea.texas.gov/Finance_and_Grants/Texas_Permanent_School_Fund.

10 Andrew Rozanov, “Who Holds the Wealth of Nations?,” Central Banking Journal 15, no.4 (2005): 52–57.

11 Rozanov, “Who Holds the Wealth of Nations?”

12 Cummine, Citizens' Wealth, 39–43; and see Appendix 1 for a discussion on the lack of a standard definition of the term “SWF.”

13 “Sovereign Wealth Funds: Generally Accepted Principles and Practices—‘Santiago Principles’,” International Working Group of SWFs, October 2008, 3, https://www.ifswf.org/sites/default/files/santiagoprinciples_0_0.pdf.

14 “Sovereign Wealth Funds in 2021: Changes and Challenges Accelerated by the Covid-19 Pandemic,” IE University Center for the Governance of Change, 2021, 26–27, https://docs.ie.edu/cgc/SWF%202021%20IE%20SWR%20CGC%20-%20ICEX-Invest%20in%20Spain.pdf.

15 “Sovereign Wealth Funds in 2021,” IE University Center for the Governance of Change.

16 “State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan,” https://www.oilfund.az/en/report-and-statistics/recent-figures.

17 “Our Work in Azerbaijan,” Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/azerbaijan; and “Rule of Law—Country Rankings,” The Global Economy.com, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_ruleoflaw.

18 "Fund for Future Generations: Sovereign Wealth Fund in Equatorial Guinea, Africa,” Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, https://www.swfinstitute.org/profile/598cdaa50124e9fd2d05b002.

19 “Our Work in Equatorial Guinea,” Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/equatorial-guinea; and “Rule of Law—Country Rankings,” The Global Economy.com.

20 Countries with lower rankings have stronger rule-of-law environments.

21 Carson Ezell, “Middle Eastern SWFs,” Harvard College Economics Review, October 23, 2021, https://www.economicsreview.org/post/middle-eastern-swfs.

22 “Investor Profile: RERF (Kiribati),” SWF Academy, https://globalswf.com/fund/RERF.

23 “Sovereign Investors 2020: A Growing Force,” PwC, 2020, 5, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sovereign-wealth-investment-funds/publications/assets/sovereign-investors-2020.pdf.

24 “Frequently Asked Questions,” GIC, https://www.gic.com.sg/who-we-are/faqs; and “Santiago Principles Self-Assessment,” IFWSF, https://www.ifswf.org/assessment/bpi-france.

25 “Oil Revenues Stabilization Fund of Mexico: Overview,” PitchBook, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/limited-partner/52308-28.

26 “Mubadala Capital,” https://www.mubadala.com/en/what-we-do/mubadala-capital; and “Real Estate & Infrastructure Investments,” https://www.mubadala.com/en/what-we-do/real-estate-infrastructure-investments.

27 “Sovereign Investors 2020: A Growing Force,” PwC, 2020, 11, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sovereign-wealth-investment-funds/publications/assets/sovereign-investors-2020.pdf.

28 “About PIF,” https://www.pif.gov.sa:443/en/Pages/AboutPIF.aspx.

29 David D. Kirkpatrick and Kate Kelly, “Before Giving Billions to Jared Kushner, Saudi Investment Fund Had Big Doubts,” New York Times, April 10, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/10/us/jared-kushner-saudi-investment-fund.html?referringSource=articleShare.

30 “Sovereign Wealth Funds Turning to Private Capital: Are They Competing or Playing alongside GPs?,” IQEQ, June 30, 2021, https://iqeq.com/insights/sovereign-wealth-funds-turning-private-capital-are-they-competing-or-playing-alongside-gps.

31 “Sovereign Wealth Funds in Motion,” Preqin, 11.

32 “Qataris Buy Remaining 30 Pct of Paris St Germain,” Reuters, March 6, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/france-psg-qatar/qataris-buy-remaining-30-pct-of-paris-st-germain-idUSL5E8E69CP20120306; and “Sovereign Wealth Funds Triple Their Investments to 450 in 2021, According to IE University and ICEX-Invest in Spain Report,” IE University, March 9, 2022, https://www.ie.edu/university/news-events/news/sovereign-wealth-funds-triple-their-investments-to-450-in-2021-according-to-ie-university-and-icex-invest-in-spain-report.

Direct investment strategies benefit SWFs by giving them greater control over their assets and allowing them to bypass additional fee structures when investing through a private equity fund.

33 In co-investing, an SWF invests alongside a partner such as another SWF, private equity fund, or venture capital fund pension fund. Co-investing helps the SWF reduce its risk exposure, while allowing for more flexibility in portfolio construction. Neil Buckley, “Glencore-QIA Deal for Rosneft Stake Starts to Lose Its Lustre,” Financial Times, January 18, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/c735dc00-dccf-11e6-86ac-f253db7791c6.

34 Tim Logan, “How Eight Fancy Boston Condos Figure Into a Fight Over the Saudi Throne,” Boston Globe, March 30, 2021, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/03/30/business/how-eight-fancy-boston-condos-figure-into-fight-over-saudi-throne.

35 Cory Bennett, “How China Acquires ‘the Crown Jewels’ of U.S. Technology," Politico, May 22, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/05/22/china-us-tech-companies-cfius-572413; and Erica Hanichak, Lakshmi Kumar, and Gary Kalman, “Private Investments, Public Harm: How the Opacity of the Massive U.S. Private Investment Industry Fuels Corruption and Threatens National Security,” Transparency International, December 2021, 23, https://secureservercdn.net/166.62.106.54/34n.8bd.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Private-Investments-Public-Harm-How-the-Massive-and-Opaque-US-Private-Equity-Industry-Fuels-Corruption-and-Threatens-National-Security.pdf?time=1664249759.

36 Hanichak, Kumar, and Kalman, “Private Investments, Public Harm,” 23.

37 Jack Farchy and Neil Hume, “Glencore and Qatar Take 19.5% Stake in Rosneft,” Financial Times, December 10, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/d3923b08-bf09-11e6-9bca-2b93a6856354.

38 One particularly interesting facet of the deal was that “Glencore’s actual equity stake in Rosneft was only about 0.5% and Qatar’s just under 5%.” See Farchy and Hume, “Glencore and Qatar Take 19.5% Stake in Rosneft.”.

39 Scott Patterson and James Marson, “Glencore, Qatar Sell Rosneft Stake to Chinese Firm in $9 Billion Deal,” Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/glencore-qatar-sell-14-stake-in-rosneft-to-chinese-energy-company-1504881233.

40 Stephen Blank, “Kremlin Ties Rosneft Closer to China,” Jamestown Foundation, November 8, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/kremlin-ties-rosneft-closer-to-china.

41 Vneshtorgbank (VTB) is one of Russia’s largest state-owned banks. It is subject to a variety of sanctions, including full blocking sanctions by the U.S. Treasury Department in response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. See “U.S. Treasury Announces Unprecedented & Expansive Sanctions Against Russia, Imposing Swift and Severe Economic Costs,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, February 24, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0608.

42 “About Us,” Norges Bank Investment Management, accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.nbim.no/en/organisation/about-us.

43 David Pegg, “Angola Sovereign Wealth Fund’s Manager Used Its Cash for His Own Projects,” Guardian, November 7, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/07/angola-sovereign-wealth-fund-jean-claude-bastos-de-morais-paradise-papers.

44 Michael Stothard and Jane Croft, “SocGen Agrees €963m Settlement With Libyan Investment Authority,” Financial Times, May 4, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/7dc88450-3094-11e7-9555-23ef563ecf9a.

45 “Sovereign Wealth Funds 2021,” IE University Center for the Governance of Change, 24–25.

46 “IFSWF Members’ Experiences in the Application of the Santiago Principles,” Report Prepared by IFSWF Sub-Committee 1 and the Secretariat in Collaboration With the Members of the IFSWF, IFSWF, July 7, 2011, 40, https://www.ifswf.org/sites/default/files/Publications/stp070711_0.pdf.

47 “Santiago Principles,” International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds.

48 “OECD Guidance on Sovereign Wealth Funds,” Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), accessed July 29, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/oecdguidanceonsovereignwealthfunds.htm.

49 “OECD Guidance on Sovereign Wealth Funds,” OECD.

50 “OECD Guidance on Sovereign Wealth Funds,” OECD.

51 “State-Owned Enterprises and Corruption: What Are the Risks and What Can Be Done?,” OECD, August 27, 2018, http://www.oecd.org/fr/corruption/state-owned-enterprises-and-corruption-9789264303058-en.htm; “Anti-Corruption and Integrity in State-Owned Enterprises,” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-corruption-integrity-guidelines-for-soes.htm; and Rajni Bajpai and Bernard C. Myyers, “Chapter 3: State-Owned Enterprises,” in “Enhancing Government Effectiveness and Transparency: The Fight Against Corruption,” World Bank, September 2020, 94–121, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/235541600116631094/enhancing-government-effectiveness-and-transparency-the-fight-against-corruption?cid=gov_tt_gov_en_ext.

52 “Sovereign Wealth Funds,” United States Government Accountability Office; and “Assessing the Economic and National Security Implications of Sovereign Wealth Funds and Foreign Acquisition,” Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate Hearing, November 14, 2007, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg50364/html/CHRG-110shrg50364.htm.

53 “Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative,” EITI, https://eiti.org; and “Open Contracting Partnership,” Open Contracting Partnership, https://www.open-contracting.org.

54 “About Us," International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, https://www.ifswf.org/about-us.

55 Pjotr Sauer, Jake Cordell, and Felix Light, “A Royal Mark Up: How an Emirati Sheikh Resells Millions of Russian Vaccines to the Developing World,” Moscow Times, July 10, 2021, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/07/09/a-royal-mark-up-how-an-emirati-sheikh-resells-millions-of-russian-vaccines-to-the-developing-world-a74461; and Rolf J. Wideroe and Markus Tobiassen, “Sputnik for Sale,” VG Nett, June 3, 2021, https://www.vg.no/spesial/2021/sputnik/index-en.html.

Chapter 2: Corruption Risks Within Sovereign Wealth Funds

As sources of long-term, patient capital, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) offer immense potential for countries to achieve their national development goals. Yet as the extensive list of examples in this compilation will document, SWFs are at grave risk of embezzlement, fraud, political manipulation, and other corrupt uses. At the center of the problem is a lack of transparency and accountability, which limits access to comprehensive, accurate data. Available data on SWFs is extremely limited, which creates opportunities for bad actors to abuse funds for their own interests. Little is known about the investments, operations, or internal management of the vast majority of funds around the world, which collectively manage over $11.5 trillion in assets.1 Without this detailed financial and operational information, the door is being left wide open for rapacious managers and political elites to misappropriate investment earnings. Their actions deprive citizens and other stakeholders of the opportunity to equally and justly benefit from fund proceeds.

This chapter highlights the many types of corruption and political risks inherent to the SWF industry and demonstrates that recent efforts to improve transparency have fallen woefully short. SWFs should be required to disclose far more extensive and detailed information about the way they develop strategies, manage assets, compensate executives, engage financial intermediaries, and report to political overseers. Only by expanding the availability of this critical data can SWFs become truly accountable to their public constituents.

The Secret Lives of SWFs

Operating as government-owned or government-controlled investment vehicles, SWFs acquire assets in private and public financial markets both in their home countries and abroad. Having state ownership in some ways sets the SWF industry apart from the private investment fund industry, which includes hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity. First, the stated missions of SWFs can go beyond maximizing investment returns; for example, they can aim to achieve macroeconomic stability or realize economic development initiatives domestically. Rather than pursuing speedy exits, SWFs often have long-term horizons and operate as passive investors that take minority rather than controlling stakes in target companies. Finally, there is an explicit political layer that distinguishes SWFs from private investment funds. Without having fiduciary duties to private investors and clients, SWFs are completely beholden to the governments that endow them. Politicians have considerable power to shape SWF investment strategies to pursue explicit political goals.

Yet even though their home governments can exert influence over their operations, SWFs in practice behave very similarly to certain types of private investment funds. Structurally, SWFs are often set up identically to private equity funds, with capital committed to the fund managed by an external general partner. This investment model endows the general partner with greater autonomy to apply expertise and develop portfolio strategies, but it also can result in bloated financial fees and crony relationships that undermine the fund’s financial performance. In contrast to popular perceptions, many SWF investments do not end up in publicly traded companies that have strictly regulated transparency obligations and fiduciary responsibilities. Just like their counterparts in the venture capital, private equity, and hedge funds industries, SWFs often purchase minority stakes in unlisted, privately held companies.2

This shared investment preference results in clear similarities in how both SWFs and investment funds are regulated. Most countries require little, if any, transparency from investment funds (including SWFs) about transactions made outside of public markets. In the United States, for example, SWFs are held to the exact same regulatory requirements as private pools of capital.3 SWFs are only required to publicly disclose equity stakes equal or greater to 5 percent of publicly traded companies. Any remaining investments in privately held companies need not be disclosed to shareholders, the general public, or regulatory authorities; for these investments, SWFs are on their own to decide what information to disclose. SWFs have adopted a number of rationales to justify preserving this opacity around their investments, including the threat of domestic political short-term pressures that could undermine their long-term investment strategies. The end result is that with few exceptions, records of SWF investments in unlisted assets—whether a private company or a real estate project—are not publicly available.

The overlap between SWFs and private investment funds is even more pronounced by the fact that many SWFs have become increasingly large investors in private equity, a sector notorious for its opacity.4 From 1984 to 2007, twenty-nine SWFs made more than 2,500 direct private equity investments worth a total of $198 billion.5 Indeed, SWFs comprise nineteen of the top forty institutional investors in private equity worldwide.6 In the wake of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, SWFs have even begun accruing substantial debt and using leverage to fund some investments—another trademark strategy of the private equity industry. SWFs also often act as coinvestors with massive private equity funds. Furthermore, SWFs have adopted their own arcane corporate structures called subfunds to coordinate sectoral investments. For example, Egypt’s SWF includes four subfunds, each with its own governance, legal structure, investment process, and independent board.7 These vehicles add a layer of opacity and complicate outside analysts’ ability to understand the true extent of their holdings.

Instead of enforcing transparency, regulators work to limit the “control” SWFs can exert over the companies they acquire stakes in. The majority of SWF investments, whether through private equity or other direct investments, are made in international markets rather than domestic markets. The extensive use of government-owned assets to buy foreign companies has given rise to suspicions about the political motives behind SWF decisions, which could disrupt markets in support of government interests.8 Countries such as France, Germany, and the United States are putting in place increasingly strict protocols for evaluating whether SWF investments are being made in sensitive sectors and therefore could generate national security or corporate espionage concerns. Yet many of these protectionist procedures are classified, and it can be difficult for investors to learn when government scrutiny of SWFs investments is ongoing. SWFs operate in a climate of secrecy, with few if any windows into their operating behavior.

Voluntary Self-Regulation Has Made Only Minimal Progress

Surprisingly, the enormous rise of cross-border SWF investments has not sparked the creation of a centralized international regulatory body to oversee the industry. Instead, growing nervousness among countries hosting SWF investments compelled representatives from twenty-three leading funds to found the International Working Group of SWFs in 2008. The group worked together to develop a set of twenty-four voluntary principles, known as the Santiago Principles, to improve transparency and governance. These voluntary standards ask SWFs to define their policy purposes, government arrangements, roles and responsibilities, and ownership rights, among other issues.9 Widespread adoption of such principles was intended to discipline SWF behavior and reassure host countries and the general public about the intentions behind these investments, as well as potentially forestall protectionist actions.10 However, voluntary participants’ compliance with the Santiago Principles still leaves much to be desired. The International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) has no power to enforce its own standards, and naming and shaming efforts by other nongovernmental organizations have been mostly absent. This means that only a few SWFs fully adhere with these basic good governance standards.

Moreover, even those SWFs adhering to the Santiago Principles still fall short of ensuring needed transparency. According to the principles, publicly declaring fund objectives does not entail the release of annual reports that provide in-depth information on how the SWF plans to achieve its objectives. Moreover, there is no clause requiring SWFs to disclose essential information on their financial positions, such as audited statements, that could shed light on the volume of assets under management or on the use of debt instruments and leverage. Although most SWFs report that information to their host-country governments, it is not sent to any international body, such as the International Monetary Fund, that could impartially validate and share the data with third parties. What is left is a highly decentralized system, where SWFs are free to invest trillions abroad but are not required to disclose any comprehensive information on their activities to the public.

The uneven progress toward full transparency is best illustrated through an analysis of the SWF Scoreboard. Developed and run by Edwin M. Truman and colleagues for more than a decade, the SWF Scoreboard aggregates publicly available information (“fund websites, annual reports, and ministries of finance, and other public sources such as IMF reports”) and ranks SWFs on thirty-three elements that cover structure, governance, transparency, and accountability. A higher score indicates that a SWF is implementing more robust governance reforms and disclosing more about its investment activities. Table 1 lists the top ten and the bottom ten SWFs according to the 2019 scores, which range from 11 to 100.

| Table 1: 2019 SWF Scoreboard Rankings | |||||

| Top Ten | Bottom Ten | ||||

| Country | Fund | Score | Country | Fund | Score |

| Norway | Government Pension Fund Global | 100 | Qatar | Qatar Investment Authority | 46 |

| New Zealand | New Zealand Superannuation Fund | 94 | Saudi Arabia | Public Investment Fund | 39 |

| United States | Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund | 93 | Russia | Russian Direct Investment Fund | 37 |

| Chile | Economic and Social Stabilization Fund | 92 | United Arab Emirates | Emirates Investment Authority | 36 |

| Azerbaijan | State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan | 92 | Kiribati | Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund | 35 |

| Canada | Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund | 91 | Brunei | Brunei Investment Agency | 30 |

| Timor-Leste | Petroleum Fund of Timor-Leste | 91 | Algeria | Revenue Regulation Fund | 26 |

| Chile | Pension Reserve Fund | 89 | United Arab Emirates | Dubai World | 24 |

| United States | Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation | 88 | Libya | Libyan Investment Authority | 23 |

| Australia | Future Fund | 87 | Equatorial Guinea | Fund for Future Generations | 11 |

Source: Julien Maire, Adnan Mazarei, and Edwin M. Truman, “Sovereign Wealth Funds Are Growing More Slowly, and Governance Issues Remain,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, February 2021, https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/sovereign-wealth-funds-are-growing-more-slowly-and-governance-issues |

|||||

At the top of the list is Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global, which has consistently demonstrated a world-leading commitment to transparency. The fund’s portfolio value is updated in real time on its website, and it publishes a lengthy annual report detailing board votes, shareholder resolutions, and engagement with target companies, especially on environmental, social, and corporate governance.11 Other SWFs have instituted best practices that hold them accountable to elected officials. Both Australia and New Zealand require managers of their respective SWFs to submit reports regularly to their ministers of finance and, in turn, members of their national parliaments.12 The funds themselves are still completely separate from political institutions and intended solely to pursue profit, but they do not operate in a black hole and are accountable to regulators and monitors.

It is the more advanced democracies that enact stronger arrangements to ensure that SWFs release necessary information. Several funds based in the Middle East, such as the Qatar Investment Authority, have been reducing the amount of information available on their websites and in their annual reports. Singapore’s SWF, Temasek, prioritizes private deals across Asia, either through private equity funds or direct investments in fast-growing sectors such as real estate. Both investment strategies thrive on opacity.13

One of the most important predictors of strong transparency scores on the SWF Scoreboard is a country’s rank on other indexes of good governance. For example, research into SWFs has found a strong correlation between a country’s scoreboard results and the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicator of Voice and Accountability; Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index; and the Polity IV indicator of democracy.14 SWF management may often be a reflection of other wider institutional reforms: where democracy and good governance are weak, SWFs will likely fail to disclose the necessary information to track their operations.15

Parsing the Data Crumbs

The end result is that regulators, journalists, civil society activists, academics, and investors alike are left with regrettably little information about how a large number of SWFs from around the world operate. The little data that are available remain incomplete and prohibitively expensive for most researchers. The first stop for most analysts is third-party aggregators, such as PitchBook, Preqin, and FactSet. These services pull together both publicly available data and insider information to construct a detailed profile of each SWF, including estimated size, investment behavior, performance, intermediary relationship, and governance structure. Because SWFs are government-connected entities, much of the data concern what might be considered public finances, thereby requiring openness and transparency. The global Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute offers similar coverage of self-reported investment patterns through its pricey subscription service. Yet third-party aggregators impose pricey subscriptions on accessing the data, limiting the ability of law enforcement authorities around the world to track how money flows in and out of SWFs.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission collects and makes publicly available basic information about the private investment fund industry (which includes a small number of SWFs), including manager information and fund size. Funds must fill out somewhat detailed forms about their makeup, but they do not have to reveal their actual investments or performance. Regulators, including those tasked with monitoring foreign investments, are often completely reliant on the private, third-party aggregators mentioned above to gain visibility into SWF activities, increasing the financial and logistical obstacles to undertaking proper due diligence. Only in rare cases are data freely available about how SWFs are managing their assets. For example, the Sovereign Investment Lab based at Bocconi University in Italy has built a database on the investments of twenty-nine SWFs, but this includes those equity stakes in publicly traded companies since they appear in public disclosures released in various jurisdictions.

Moreover, private, third-party aggregators are significantly dependent on SWFs sharing their underlying data. If an SWF, particularly one operating in a nondemocratic country, chooses not to disclose an equity investment, it is unlikely that any of the aggregators will be able to pick up, much less monitor, that activity. In addition, there are large segments of SWF portfolios that are almost completely absent. Bond markets remain mostly opaque, as are investments in domestic asset classes, which for some funds comprise the bulk of assets under management (such as in Russia).16 There are finally few mechanisms for verifying whether the self-reported data are accurate.

Home country regulators presumably collect these data on investments, but only in rare instances (such as in Norway) is any of that information made public. Instead, analysts often glean information on fund objectives and governance from some SWF annual reports and websites. For example, a recent study demonstrates the evolution of declared investment strategies over time as well as innovation and collaboration between SWFs.17 However, annual reports do not contain audited financial statements, nor do they outline in any detail the breadth of investments pursued by funds. Learning about more sensitive topics from these reports is next to impossible, whether it be full lists of nongovernmental investors (foreign and domestic), management fees paid to private investment funds, executive compensation, key relationships with intermediary brokers, or corporate structures facilitating investments (especially through offshore companies).

Leaked documents provide perhaps the only window into some SWFs. In 2018, the global Paradise Papers leak revealed rampant cronyism and corruption within Angola’s SWF, Fundo Soberano de Angola (see chapter 4). The fund paid millions of dollars in management fees through uncompetitive tenders to investment managers closely linked to the country’s ruling elites.18 Even supposedly better-governed funds have been implicated in serious scandals following documents being leaked into the public sphere. A trove of tens of thousands of internal documents from Australia’s Future Fund led to accusations of tax avoidance and exorbitant fees paid out to external fund managers.19 However, such leaks rely on whistleblowers sharing the truth about SWF activities with the wider public—thus, leaks are welcome but highly imperfect mechanisms for ensuring transparency.

The Risks of Opacity

The risks of this opacity persisting within the SWF industry are immediate and serious. Collectively, SWFs invest trillions of dollars across a host of developing and developed countries. At the macroeconomic level, a lack of transparency raises the specter of real destabilization risks if funds were to fail, be mismanaged, or rapidly withdraw funding from target markets. Lack of oversight into SWFs’ substantial investments could inflate dangerous equity price bubbles.20

Opacity also carries political consequences. Over the past two decades, much of the push to better regulate the SWF industry has been spurred by concerns about political motivations driving investment behavior. To what degree are SWFs independent from the governments that create them? Without transparency, it becomes significantly more difficult to differentiate whether investment decisions are being made on a purely financial basis or with political aims in mind, such as the transfer of corporate intellectual property to domestic companies. In the aftermath of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, an array of SWFs began sweeping up highly discounted assets in troubled developed economies and were credited with partially bailing out the U.S. and European banking systems to the tune of $63 billion.21 Although protectionist sentiments globally have led to more restrictive regulations around SWF investments, a growing body of evidence is revealing that the motivations behind these investments are sometimes geared toward the pursuit of other political goals. U.S. policymakers, for example, have passed much stricter protocols for assessing foreign investments in sensitive sectors in part because of fears that SWFs could be exploiting opacity to acquire information and technology critical to national security.

Some of those fears have not gone unfounded. In examining a dataset of equity stakes taken in U.S. publicly traded firms, research has shown that SWFs have become increasingly attracted to investing in politically active companies.22 Their investments help provide a type of “foreign state insurance,” shielding their home government from possible potential risk but also opening up lobbying opportunities within the U.S. political process.

SWFs that fail to disclose proper information to regulators and the general public are uniquely vulnerable to political co-optation, mismanagement, and outright corruption. The vast sums of money tied up in these funds offer an array of personal and political dividends to the government elites that create them. As the assets of SWFs surged in 2011, nearly three-quarters of all assets under SWF management were held by nondemocratic governments.23 These financial assets can be used to keep incumbent governments in power, for example, by buying citizens’ loyalty and co-opting or neutralizing domestic competitors.24 Therefore, the shield of opacity can hide the use of SWFs as a strategic financial tool designed to aid ruling elites.

A good example of this is Libya’s SWF. Established in 2006, the Libyan Investment Authority’s (LIA) mandate was to invest substantial Libyan financial assets earned from its oil industry into a more diversified portfolio that could function as a reserve fund.25 Even though the fund was carefully managed in near complete secrecy by Muammar al-Qaddafi and his family, it received an influx of foreign capital and took numerous positions in Western companies, such as General Electric, AT&T, and Juventus Football Club.26

It was not until internal fund documents were leaked to the British nongovernmental organization Global Witness that the world began to learn about of the full extent of the LIA’s investment behavior, including the $64 billion amassed.27 A later audit by Deloitte suggested that upward of 20 percent of the fund’s value had disappeared into a black hole, presumably lining the pockets of the ruling elite.28 Accusations were also leveled at Goldman Sachs, whose investment managers allegedly paid prostitutes and bought private jets and stays in five-star hotels in an attempt to woo business from the LIA.29 Ultimately, the fund became one of the first targets of sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council amid rampant accusations from insiders of corruption and misappropriation by the Qaddafi government and its external partners.30

Recent work on African states has drawn attention to a new category of unofficial SWFs that behave almost identically to their official counterparts but disclose even less information to the general public.31 Known as extra-budgetary resource funds, these vehicles operate in near complete secrecy; they do not appear in annual budgets or comply with even basic reporting or audit standards. These funds provide nondemocratic governments with the ability to invest in projects that can pad the pockets of loyal elites and help the regime stay in power longer.

In sum, the corruption risks inherent to SWFs are enormous, as several of the chapters in this compilation attest. At least $4.5 billion was stolen from Malaysia’s SWF (see chapter 3), in what became the “world’s biggest financial scandal.”32 The scandal wound up snaring individuals from over ten countries, including the then Malaysian prime minister. In 2020, the prime minister was sentenced to twelve years in prison for engaging in corruption and abuse of power. A recent investigation of Uzbekistan’s SWF implicates the country’s leadership in directing tens of millions of dollars to a corporation run by a relative of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev.33 As more and more countries begin the process of creating their own funds, there is a real threat of continued corruption unless good governance standards are put in place.

Strengthening Transparency Will Improve Accountability

Given the macroeconomic, political, and corruption risks associated with SWFs, there must be greater transparency across the industry as a whole. What types of information should SWFs disclose? First, fundamental information on SWF finances needs to be disclosed: the value of assets under management; the short- and long-term performance indicators; the allocations across markets and investments; the benchmarks; and the environmental, social, and corporate governance metrics. Ideally, these data points would be validated through external audits. This type of information should be required from the entire pooled investment industry, which thrives on the same opacity that SWFs do and is vulnerable to many of the same problems.

Organizationally, SWFs should also better identify their key policy objectives as well as their governance structures, including board selection and responsibilities and the fund’s relationships with policymakers and regulators. Alongside releasing more information about SWF internal operations, countries need to carve out a greater role for popularly elected legislatures and independent agencies to supervise those activities and ensure that investments are being made in the national interest. Improving reporting mechanisms is a key step along that path, but those in charge of public oversight must also be empowered to hold SWF managers accountable. Transparency fosters accountability only when stakeholders and other observers can act on the disclosed information and prevent the co-optation of SWFs for political motivations.

Voluntary disclosure is not enough. Although the Santiago Principles provide a template for cooperation between funds, until a major international organization steps in to publish true third-party evaluations, compliance and disclosure practices will likely remain incomplete. So far, fragmented efforts to name and shame SWFs for neglecting good governance principles have not led to real and durable change. Given the importance of cross-border investments within SWF portfolios, the international community must take a stronger stance and empower a body to monitor SWF governance.

SWFs have much to gain by being more transparent about their operations and investment decisions. Companies targeted by more transparent SWFs typically generate higher investment returns, suggesting that transparency can be a strong signal of quality due diligence and monitoring on the part of SWFs.34 Transparency also allows for more objective evaluations on whether SWFs are actually meeting their policy and performance objectives, which should improve funds’ abilities to raise and borrow capital. Conversely, SWFs that are vulnerable to political interference see lower returns on their investments and more negative deterioration of long-term performance in targeted companies.35 Investors have expressed frustration with a lack of access to timely statistics from SWFs based in Middle East, particularly when large withdrawals occurred shortly after oil prices fell.36 In that regard, transparency is a win-win for the vast majority of SWF stakeholders. If entrenched elites are allowed to monopolize management and disclosure decisions, corruption will thrive.

Notes

1 William Megginson, Asif Malik, and Xin Yue Zhou, “Sovereign Wealth Funds in the Post-pandemic Era,” Journal of International Business Policy 6 (April 2023): 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-023-00155-2.

2 Veljko Fotak, Bernardo Bortolotti, William Megginson, and William Miracky, “The Financial Impact of Sovereign Wealth Fund Investments in Listed Companies,” unpublished working paper, University of Oklahoma and Università di Torino (2008).