New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

Source: Getty

Comparison of the two countries’ social media environments shows how tech companies and policymakers can work to combat autocratic coercion.

Across the world, governments and Big Tech companies have diverged on how social media platforms should moderate political content and who gets the final say. While numerous studies on platform governance and content moderation have drawn on findings from relatively liberal contexts such as the United States and Western Europe, major platforms also operate in illiberal contexts in which governments exert undue pressure to restrict media freedom and crack down on critics.

This paper compares two contexts with different degrees of illiberality: India and Thailand. Through desk research and interviews with key stakeholders, it analyzes how the Indian and Thai governments have used legal, economic, and political forms of coercive influence to shape platforms’ moderation of political content. Further, the paper identifies major types of coercive influence that may explain why platforms comply or do not comply with government demands. The analysis finds that India’s government under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been able to exercise greater leverage than the Thai government over social media content regulation because of India’s large market size and regulatory measures that give the government sweeping powers over tech platforms.

Despite attempts to standardize community guidelines and rules of content moderation in line with international human rights law, tensions often arise when platforms and governments diverge in their interpretations of what constitutes acceptable political content and who has the power to decide. Governments exert coercive influence that shapes platforms’ content moderation in three intertwined ways.

Three main factors shape the extent to which platforms are driven to comply with government demands:

From this understanding of how transnational platforms are influenced at multiple levels by the governments of their market regions, clear takeaways emerge for policymakers seeking to counteract illiberal governments’ coercive influences on political content moderation by platforms, prevent censorship, and circumvent cronyism when it comes to platform regulation. Critically, rebalancing power relations between governments, platforms, and users will be essential for these measures to be effective.

Contemporary debates on political content moderation typically revolve around concerns that hate speech and disinformation might undermine social cohesion and democratic integrity in the United States and Western Europe. In these regions, liberal traditions and institutions largely guarantee judicial independence and freedom of expression. But in illiberal and/or autocratic contexts, from Türkiye to Vietnam, governments have exploited the international debate over platform regulation to coerce tech companies to censor—rather than moderate—content. Companies that seek to sustain their business in these countries are increasingly under pressure to suppress content and information that government actors view as challenging their status quo.1 This development has especially intensified in South and Southeast Asia, where governments have cracked down on journalists and oppositional civil society.

This paper analyzes how the governments of India and Thailand have exerted pressure on platforms to moderate political content, especially during anti-government protests, and what drives these governments’ differing abilities to do so effectively. In this context, political content refers to information related to the government, including various state agencies and their affiliates, and public discussion and criticism of these entities’ policies and practices. We focus our analysis on three platforms that dissidents often use to criticize their governments and build networks of support: Facebook (owned by Meta), X (formerly known as Twitter), and YouTube (owned by Google). The ability to publicly share content makes these platforms highly impactful for dissidents—and a thorny problem for illiberal governments.2 By examining how the Indian and Thai governments have responded, we develop a typology of government influence on platforms. Further, we show how structural factors—including a government’s reliance on foreign tech companies, a country’s market potential, and existing channels through which to contest government policies—underpin differences in governments’ ability to coerce tech platforms.

The methods of data collection used for this paper combine desk research with online and onsite personal communications with platform representatives and civil society members affected by the political content moderation policies in India and Thailand. The authors asked senior platform representatives who deal (or previously dealt) with content moderation and curation about their respective companies’ core values and approaches to content moderation. Among other things, we sought to understand whether the laws of their countries of origin or the laws of their market regions prevailed when the two clashed. In India, we talked to six platform executives who worked on country-level platform policies, one journalist whose critical content about the government had been taken down, and one digital rights advocate. In Thailand, we talked to two individuals who had previously worked for country and regional offices of Facebook and X, one digital rights advocate, two dissidents who were administrators of pages taken down by these two platforms, and one chief executive of a traditional media outlet that had been affected by the Thai government’s online censorship, and one expert on taxation of digital platforms. Their names have been anonymized at their request.

The paper begins by situating this study in the existing debates on content moderation and platform governance. Next, it details legal, economic, and political forms of coercive government influence on platforms’ political content moderation. Then, it explains the factors that underpin the Indian and Thai governments’ differing abilities to pressure platforms. Finally, it offers brief recommendations for policymakers trying to address governments’ unduly coercing content moderation.

Internal and external forces, including government influence, shape social media platform governance.3 Major platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube are primarily driven by advertising-based profit, which shapes their decisions to host and promote certain content.4 However, domestic and international campaigns against disinformation and hate speech have increasingly compelled platforms to monitor, moderate, and remove content “deemed to be ‘irrelevant,’ ‘false,’ or ‘harmful.’”5 Platforms’ terms of service and community guidelines or standards reflect processes of content moderation configured by the companies’ operational environments, the legal requirements of their host countries, cultural norms, and international human rights standards.6 Major platforms have similar, generic rules, which enables cross-platform content-sharing by users.7 These rules prohibit hateful, discriminatory, unlawful, and misleading content and the exposure of private information of users without their consent.8 Platforms also monitor local contexts and languages, combining human moderators and automated filtering to flag and remove objectionable content.9

With the advent of social media as a tool for political communications and participation, platform users are subject to overlapping domestic and international legal frameworks that govern speech. Tensions often arise when states disregard platforms’ preference for self-regulation or when platforms regulate speech that is not prohibited by the national laws of a particular market.10 Governments have invoked sovereignty to demand that platforms moderate content that could be detrimental to national interests, security, sovereignty, or citizens’ well-being.11 Increasingly, many states question the opaque processes that platforms employ to moderate content or deplatform high-ranked authorities.

Most analyses of government interventions in online content moderation look at the United States and Western Europe.12 In Europe, various regulations have increased governments’ and regional organizations’ ability to influence platforms’ community standards and content moderation filters while remaining compatible with democratic rule of law. The European Union’s Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online, e-Commerce Directive, Digital Services Act, and Digital Markets Act, as well as Germany’s Network Enforcement Act, for instance, are framed in terms of user benefits and allow for debate and modification.

Comparative insights into other contexts with weaker rule of law and restricted civil society remain scant. Illiberal and autocratic governments in Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Vietnam, for example, have blatantly requested that platforms take down or suppress, rather than moderate, content. The few analyses of content moderation in such political environments show that government regulations of online content can be used to stifle dissent and consolidate ruling power rather than foster platform accountability.13 Government figures sometimes harness their political connections and personal relationships with local platform representatives to advance censorship.14 In addition, economic measures can be politicized to make platforms more susceptible to censorship and information manipulation.15 This paper builds on these nascent insights to systematically demonstrate how governments exert coercive influence on tech platforms, and why platforms may respond differently depending on the context.

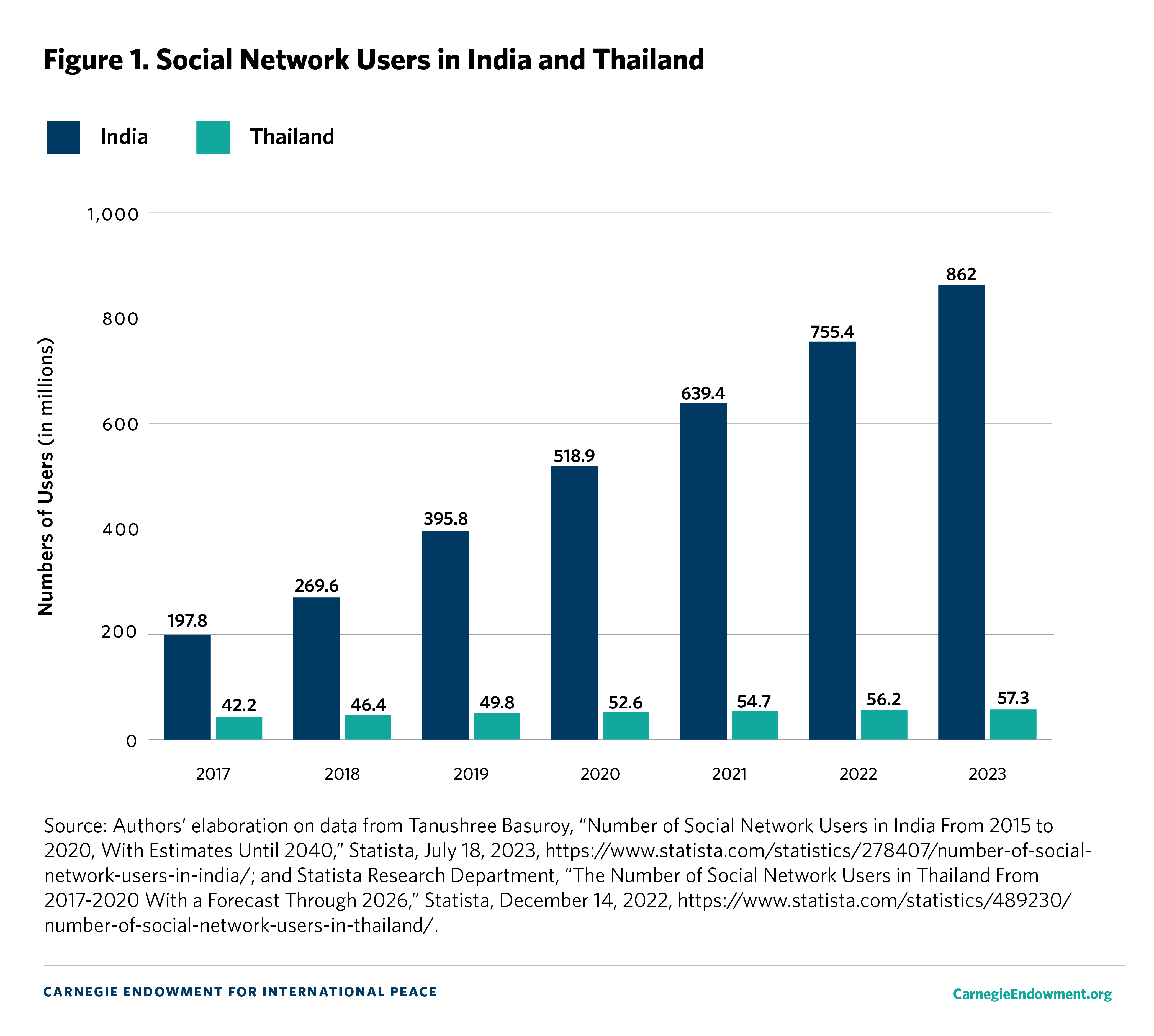

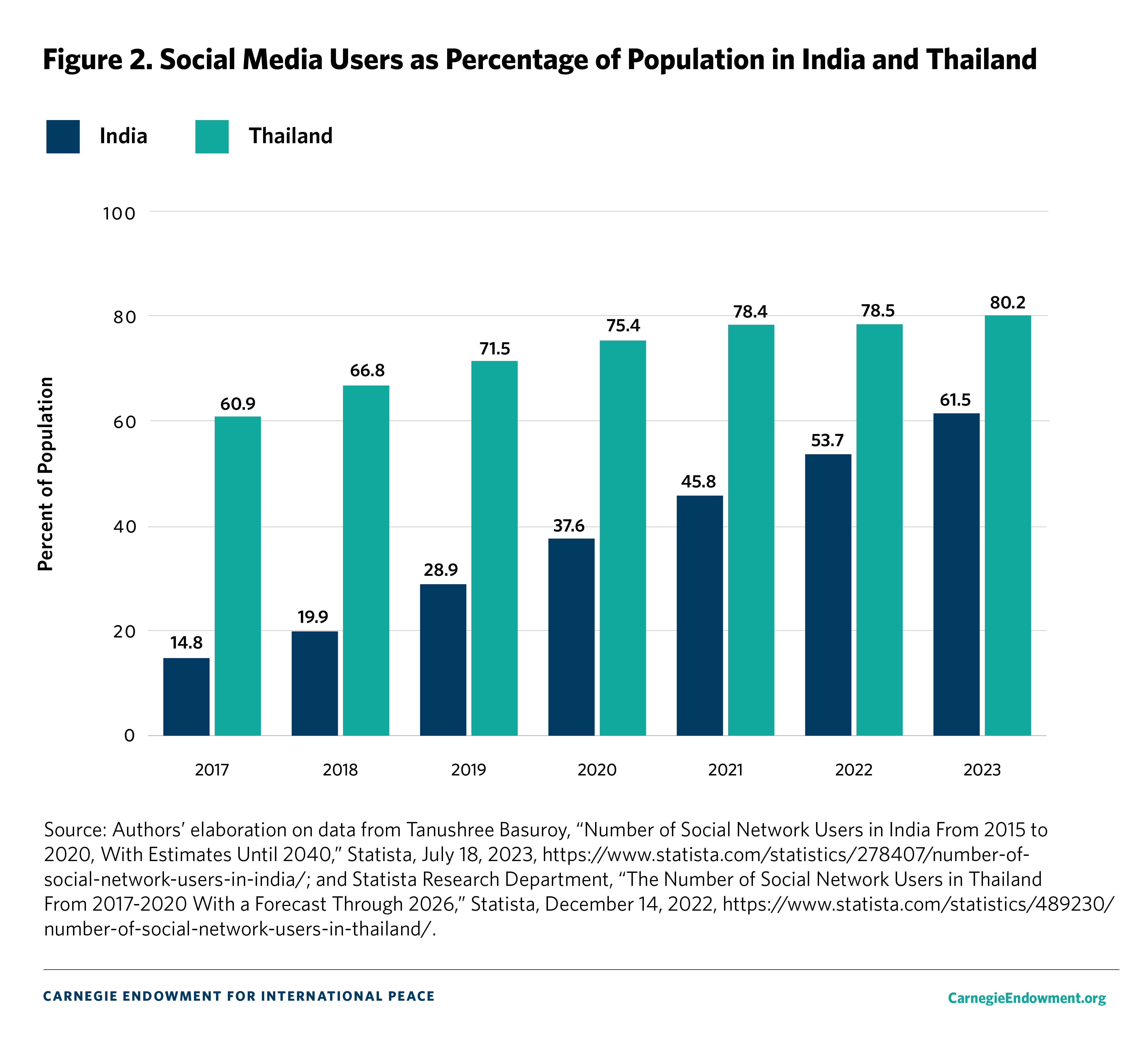

Both India and Thailand display common conditions that are crucial for understanding types of government influence on content moderation. In both countries, Big Tech companies have a huge presence. Since digitization, India’s social media usership is estimated to have risen from almost 15 percent in 2017 to approximately 62 percent of its 1.4 billion population in 2023.16 In terms of user base, India is the largest market for Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, which, along with X, are among the most-used platforms by India’s 467 million social media users.17 India also had a domestic platform, Koo, with more than 15 million subscribers since its launch in 2020, but as of July 2024, Koo appears to be shutting down.18 Meanwhile, Thailand has the highest degree of Facebook connectivity in Southeast Asia—Bangkok has been dubbed the “capital of Facebook.”19 Thailand’s social network usership has grown steadily, from 60 percent in 2017 to 80 percent of its 70 million population in 2023.20 Facebook and the messaging app LINE, followed closely by TikTok, were Thailand’s most-used social media platforms in 2023, with a penetration rate per population of 91, 90, and 78.2 percent, respectively.21 Despite originating in Japan, LINE presents itself as a localized platform and has frequently collaborated with state agencies, local media outlets, and banks in Thailand.22

In addition, India and Thailand display varying degrees of internet control due primarily to their declining democratic qualities. India is identified as an “electoral autocracy” in the V-Dem Institute’s 2024 report on democracy around the world.23 But restrictions on speech preceded the current BJP-led coalition government. For example, certain sections of the Information Technology (IT) Act of 2000 provided the mechanisms for online repression by government actors. Since the BJP came to power in 2014, the central government and local governments have often used Section 66A of the IT Act, which criminalizes posting offensive messages online, to stifle critics. Even after the Supreme Court of India ruled Section 66A unconstitutional in 2015, governments have continued to use it.24 Thailand’s democracy collapsed after the military coup in 2014. Though Thailand held elections in 2019, the V-Dem Institute labeled the country a “consolidated autocracy” until mid-2023. Although the May 2023 election saw executive power formally transition to a former opposition party, the monarchy-military nexus continues to loom large. As of this writing, Thailand is classified by the V-Dem Institute as an “electoral autocracy.”25

In both countries, autocratization has occurred alongside growing controls over the digital space. The Thai and Indian governments restrict social media content that they deem a threat to “national security” (or the monarchy in the case of Thailand), “public order,” or “friendly relations with foreign States,” or for being “inciteful.”26 In India, the 2021 IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules have tightened the government’s grip on the internet.27 In Thailand, the 2007 Computer-Related Crime Act (CCA), which was amended in 2016, and its related ministerial announcements, have increased government control over internet service providers (ISPs), online media, tech platforms, and users.28

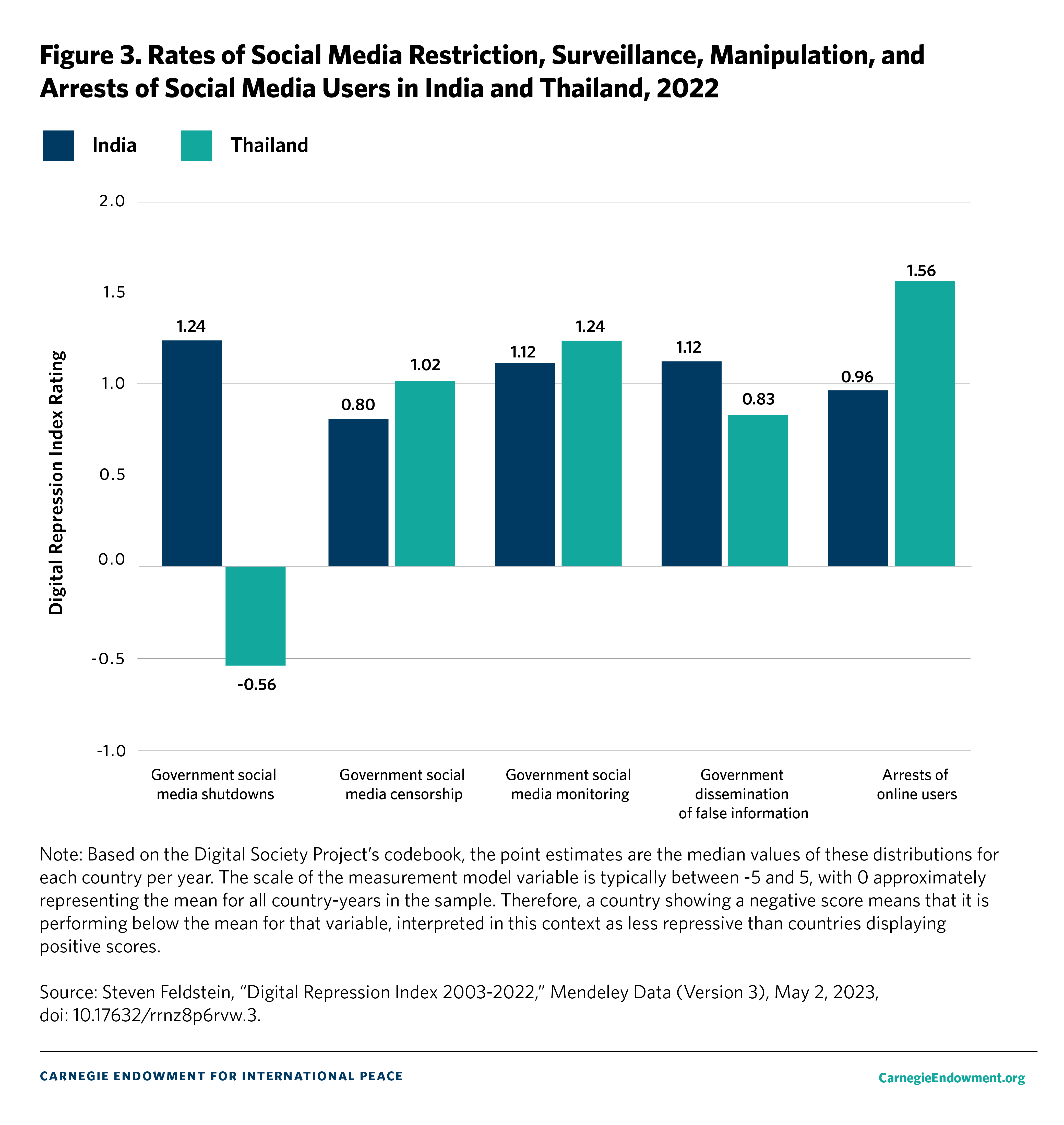

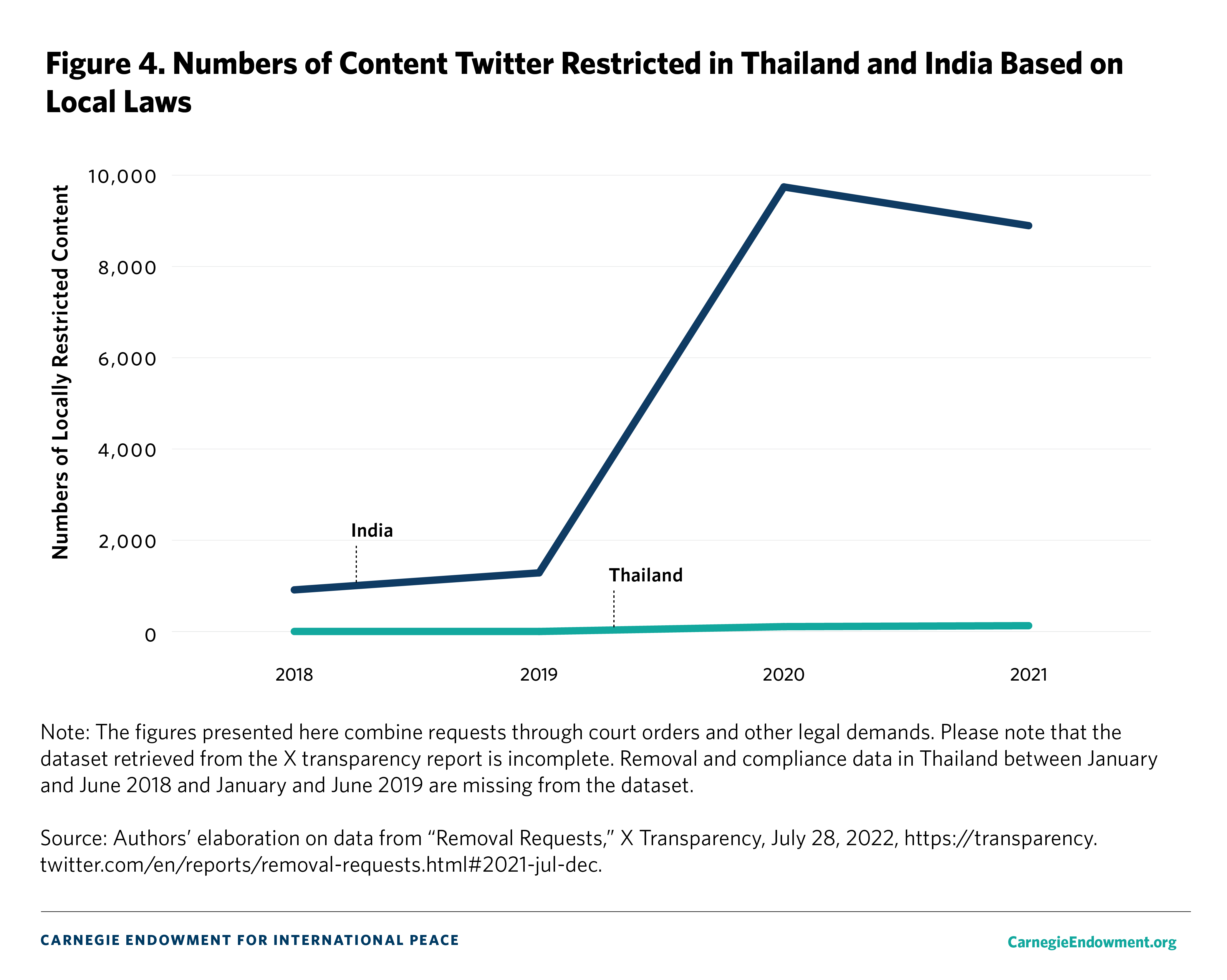

These laws provide for a broad scope of interpretation and contain vague notions of what constitutes online threats to national security and public order. This allows governments and state authorities to opportunistically use the laws for further digital control. In India, for example, the Department of Telecommunications holds the power to issue licenses to ISPs, which gives them significant leverage to order ISPs to block any website or subscriber without informing the users.29 The government can also stifle platforms through internet shutdowns.30 From 2012 to April 2024, state governments in India shut down the internet 812 times—more than any other country in the world.31 Similarly, after the 2014 coup, Thailand’s government increasingly filtered and censored online content considered “lèse majesté” (offensive to the monarchy) through the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society (MDES), the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC), the cyber crime police, and the courts.32 As shown in figure 3, Thailand has higher rates of social media monitoring, censorship, and arrests of online users. In contrast, government shutdowns of social media and government dissemination of false information feature more prominently in India.

There are, however, massive disparities between India and Thailand in terms of their economic size and how that affects platforms’ business considerations. In 2021, Thailand’s gross domestic product (GDP) was about $505.9 billion in purchasing power parity; India’s GDP was about $3.17 trillion.33 Annual growth in Thailand stagnated at the rate of 2.2 percent in 2023.34 India’s annual growth was 7.2 percent in 2022–2023.35 In 2020, ad revenues for Facebook, YouTube, and LINE in Thailand were $209.4 million,36 $149 million,37 and $36 million, respectively.38 In 2020–2021, Facebook India’s revenues crossed the $1 billion mark, with revenues increasing significantly in the following years.39 India has Meta’s largest consumer base (including Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp); some of Meta India’s top-level officials even managed the company’s operations in Southeast Asia.40 Advertising and net revenues for other Big Tech platforms in India also show a year-on-year increase.41 Google India posted a 79.4 percent rise in gross ad revenue at more than $3 billion in FY 2022.42 Both Meta and Google have deemed India a “priority market,” planning billions of dollars of investment.43 As major platforms venture into other sectors, India’s power as a large manufacturing and market destination has grown.

Governments and state agencies can enforce legal measures (including laws, executive rules, and regulations) to induce content moderation practices that are favorable to them, which this paper calls legal influence. These practices might include redesigning content filters according to legal requirements or reframing platform rules in response to threats of punitive measures (including loss of intermediary status or safe harbor protection from penalty and liability for acts of third parties who use their platforms) in cases of noncompliance. These legal measures are problematic when implemented unduly, disproportionately, and selectively to achieve objectives of control such as dissent suppression or election manipulation.44 Often, legal influence intersects with economic and political influences.

In both India and Thailand, the government’s legal authority resides in the claim that platforms operating in their territory must comply with local laws. While that may be the case, these governments subjectively interpret and arbitrarily apply their laws to tighten information controls. To force platforms to comply with local laws, the Indian and Thai governments have increased pressure through domestic ISPs and threatened to sue platforms or even evict them from the country. In addition, both governments have intimidated platforms’ local staff in retaliation for noncompliance. Finally, platforms in both countries risk losing legal protection if they fail to cooperate with the government.

Interviewees in India mentioned a convergence in the starting philosophy of local and global platforms when it came to their content moderation practices—that is, compliance with Indian laws and jurisdiction.45 In practice, the government often issues content and account takedown orders, capitalizing on vague legal definitions.

According to Section 69A of the 2000 IT Act, relevant state agencies can block access to content they deem to be “in the interest of sovereignty or integrity of India, defence of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence relating to above or for investigation of any offence.”46 The 2021 IT Rules allow the government to order a platform to take down content not included under Section 69A of the IT Act or Article 19(2) of the Indian Constitution (on restrictions to freedom of speech and expression), including content on digital news sites, over-the-top media services, and gaming platforms. For example, during the coronavirus pandemic, the government ordered Meta and X to take down or block content that criticized the government’s handling of the pandemic on grounds of being either misleading or false content. Targeted content included news reports, political commentaries, and satire.47

Government-dominated regulatory mechanisms and committees have been instrumental in further tightening the Indian government’s control over platforms. Part II of the IT Rules obligates platforms to deal with user complaints through a grievance redressal mechanism within fifteen days, enable identification of the “first originator” of messages, and develop automated tools to censor content.48 In October 2022, an amendment to the IT Rules established three-member Grievance Appellate Committees (GACs) to decide on platforms’ content moderation decisions. On April 6, 2023, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) published a notification of the IT Rules in the Gazette of India that said a government-appointed fact-checking unit could flag any online content that the central government vaguely defined as “fake or false or misleading.”49 This obligates all intermediaries, including ISPs, to remove such content within seventy-two hours. Noncompliant platforms may risk losing their legal immunity as “intermediaries” for third-party user content as provided by Section 79 of the IT Act.50 The proposed Digital India Act, which is intended to replace the IT Act, will substantially increase government control over the internet and is expected to remove so-called safe harbor protections for platforms.51

While an appellate committee is needed to address platforms’ opaque decisions on content moderation, weakening accountability mechanisms and increased political interference have called the GACs’ transparency and nonpartisanship into question. The committees are appointed by the central government. Their decisions cannot be appealed against or revised beyond citizens asking the courts to enforce their constitutionally guaranteed rights to freedom of speech and expression.52 Together with the aforementioned legal measures, the GACs may compel platforms to proactively block political content unfavorable to the government.53 Except for tepid comments on ongoing legal challenges to these rules, the major platforms have not publicly questioned the appointments to or the functioning of the GACs.

Content takedown requests disproportionately target civil society critics in India. For example, in the second half of 2020, X (then Twitter) received government requests to take down the accounts of 128 verified journalists and news outlets. This number represented 35 percent of the 361 global legal requests that the company received.54 Platforms have largely complied with government takedown orders based on Section 69A of the IT Act.55 In 2020, Meta began tracking the number of global restrictions externally imposed on its content. In 2021, there were twenty-four restrictions.56 Further, Meta’s compliance rate on Indian government requests for user data increased from 51 percent between January and June 2021 to 68.26 percent between July and December 2022.57 By 2022, major platforms published monthly transparency reports under Rule 4(1)(d) of the IT Rules. Between October 27, 2022, (when Tesla CEO Elon Musk assumed ownership) to April 27, 2023, X has fully complied with forty-four of fifty requests from the government of India, including takedowns.58

The Indian government has also leveraged its legal influence by threatening retaliation against local platform staff. In March 2021, after Twitter labeled a tweet from a spokesperson of the ruling BJP as “manipulated media,” a special cell of the central government–controlled Delhi Police raided Twitter’s offices in Delhi and Gurgaon.59 While the MeitY claimed it never threatened any Twitter employees with jail sentences, the police filed a first information report in June 2021 against India’s Twitter chief, Manish Maheshwari, in connection with a viral video of an alleged hate crime published in the platform. The prospect of his arrest prompted Twitter to transfer him to San Francisco.60 In an unprecedented development, Twitter globally removed two tweets from Indian journalist Saurav Das on Indian Home Minister Amit Shah’s comments on the Indian judiciary (without informing Das). Twitter claimed that its action was in response to the legal demands of the Indian government.61

Finally, the clash between Twitter and the government following the farmers’ protests illustrates how platforms in India risk losing legal protections if they fail to cooperate. On February 8, 2021, the government ordered Twitter to take down 1,178 accounts that they claimed belonged to Sikh and Pakistani extremist groups.62 Twitter did take down 500 accounts, but it explained that it would not remove the accounts of journalists and activists and accused the government of acting beyond its powers. In June 2021, the government accused Twitter of failing to appoint a compliance officer as required by the IT Rules and stripped the tech giant of its legal protection as an intermediary under Section 79. Twitter risked becoming the only major platform to lose its safe harbor shield for third-party content. Twitter soon fell in line with the government’s orders.

Similar strong-arm tactics are evident in Thailand. While the Indian case highlights the importance of national laws and jurisdiction, the Thai laws governing online content prioritize national cyber sovereignty, with the state possessing supreme legal authority over Thai territory and citizens.63

The CCA’s oft-cited Sections 14(1), 14(2), and 14(3) are the most powerful legal weapons for compelling ISPs to remove content that is critical of powerful government, military, and palace actors. Both the platforms and Thai authorities may share concerns about pornographic, gambling-related, and false content. But in sharp contrast with the tech companies’ community standards, the CCA does little to articulate the parameters of what constitutes unacceptable content. Instead, the CCA vaguely defines criminal content as damaging “public order or good morals,” causing panic, or offending “the security of the Kingdom.” 64 This loose definition allows for opportunistic interpretation by government authorities. Under the CCA, the MDES is responsible for requesting court orders to remove or block online content. Once the court delivers the order, it is submitted to the NBTC, which instructs tech companies to comply with the order. In cases of noncompliance, tech companies may face criminal charges and/or fines of 5,000 Thai baht per day.65 In November 2022, the MDES announced an amendment to the CCA that allows individuals to submit complaints and request platforms take down or block content. If content is deemed detrimental to national security, platforms are compelled to remove it within twenty-four hours. To date, there is no mechanism for those who create and share content to challenge these complaints.66

In addition to the CCA, the coronavirus pandemic gave the government of then prime minister Prayut Chan-o-cha pretext to impose a state of emergency. Under Section 9(3) of the resulting emergency decree, the government prohibited the publication and dissemination of any information that could affect “the security of state or public order or good moral of the people.”67 In March 2020, the government issued a new regulation that banned misleading or fear-mongering information about COVID-19. Until its cessation in September 2022, the decree was used mainly to target government critics and protesters, as well as platforms that hosted their content.68

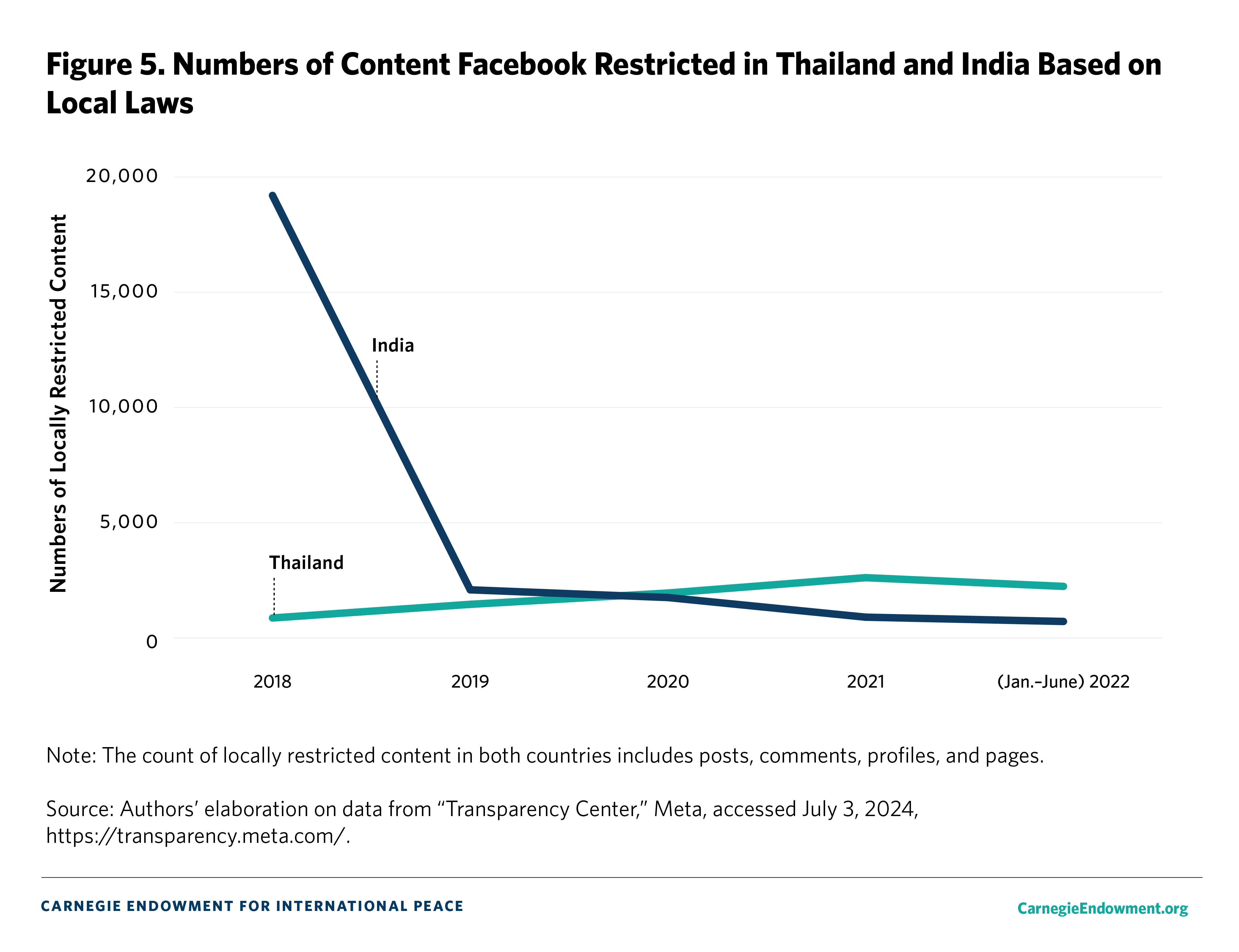

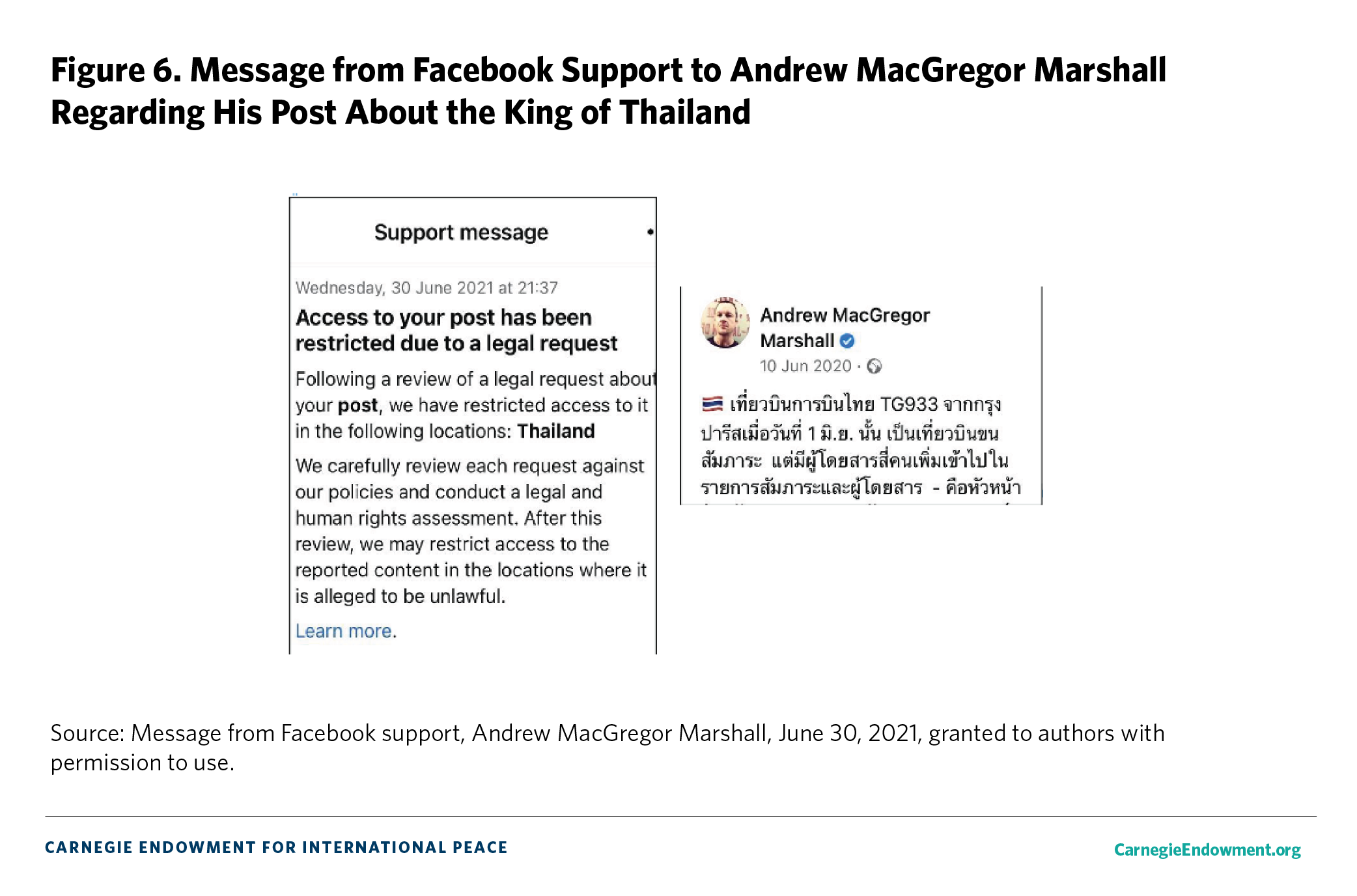

In contrast with those in India, platforms operating in Thailand tend to locally block content (a practice known as geo-blocking) that is accused of violating national laws. Between 2018 and 2021, Meta restricted domestic access to 6,900 sites that the government alleged had violated local laws.69 Google’s takedown rate was even higher. From 2009 to 2020, 28,595 items were removed from Google Search and YouTube.70 Pressure intensified after the military coup in 2014, after King Rama IX’s death in 2016, and when a scandalous video of the new king went viral on social media in 2017. During anti-government protests in 2020 and 2021, government requests to take down “illegal” and “fake” content skyrocketed.71 In August 2020, the court ordered 2,300 URLs—1,790 of which were hosted on Facebook—to be taken down.72 In the latter months of 2020 and 2021, when anti-government protests increased, Meta geo-blocked 3,580 sites, including 2,373 sites deemed offensive to the monarchy by the MDES.73 Based on its transparency report, Twitter received 178 legal demands and court orders to remove or withhold content between July 2020 and June 2021, more than any previous year.74

Thai authorities have also used the CCA to pressure domestic ISPs to solicit cooperation from U.S.-based platforms outside of Thailand. For example, in 2017, exiled dissidents shared a scandalous video of the new Thai king—who lived in Germany at the time—on Facebook, garnering about 458,000 views. In response, the NBTC ordered all ISPs and international internet gateway services to block the clip or risk losing their licenses. This was futile, as the clip posted on Facebook was encrypted and the host servers were located abroad. On May 9, 2017, the Thai Internet Service Provider Association emailed an official request to Meta (then Facebook) CEO Mark Zuckerberg. After deciding that the clip violated a local law—most likely Article 112—Facebook geo-blocked the clip in Thailand.75 However, the Facebook pages of the dissidents who shared the video, though condemned by the military junta, remained available across the country and their numbers of followers skyrocketed. Users who followed these pages and shared their alleged lèse majesté content were threatened with computer-related crime charges.76

Like their counterparts in India, Thai platform staff have also dealt with legal intimidation. In 2020, Meta’s office in Thailand faced legal threats after the MDES requested it block the Royalist Marketplace, a group run by academic dissident Pavin Chachavalpongpun with at least one million followers.77 The page shared scandalous information about the palace in coordination with anti-monarchy hashtags on Twitter. After Meta failed to respond to the court’s takedown within fifteen days, as stipulated in the CCA, the former minister of the MDES threatened to file a CCA-related lawsuit against the company. According to a former staff member, Meta was concerned that the police might charge their local team under Article 112, which carries harsh jail sentences and stigmatizes the accused. Some local staff were afraid that the authorities would go after family members serving in the Thai bureaucracy.78 One dissident who witnessed the incident unfolding mentioned that “Facebook [was] under immense pressure although they resisted [the government’s request] for quite some time. In the end, [Facebook] made a tactical decision to geo-block [the Royalist Marketplace page].”79 Twitter/X, however, has managed to avoid this kind of legal harassment despite being a key platform for young Thai activists. As of 2021, Twitter had not registered its office in Thailand and had no local staff subject to Thai laws: “This is why government pressure on [Twitter/X in Thailand] is not so intense.”80

In addition to legal influence, governments can use business-oriented incentives or threats to shape content moderation policies—what this paper calls economic influence. These may include offers of business deals, government patronage for market growth, ad revenues, reduction of taxation or threats to increase it, or loss of market access. Companies whose business model depends on revenue streams and market dominance may be motivated to accept government demands. This is especially true in big markets like India, where Meta and Google seek to retain good relationships with the government and the ruling party.81

In India, ad contributions represent a major plank of government influence over platforms. In an analysis of over 500,000 political advertisements on Facebook and Instagram from February 2019 to November 2020 (during elections season), Meta (then Facebook) boosted ads for the BJP—their “largest political client”—while allegedly undercutting ads for opposition parties.82 The main opposition party, the Indian National Congress, accused Meta of giving the BJP “favourable treatment on election-related issues” and promoting partisan ad targeting.83 Meta allegedly charged lower advertising rates to the BJP while also allowing “ghost and surrogate advertisers” to campaign for the party, bypassing Facebook’s community standards.84

As platforms seek to expand their businesses beyond social networking to other business sectors, cordial relationships with the government become essential. This has the potential to make content moderation decisions more susceptible to government influence. For example, the BJP’s Facebook ads were also funded by a firm belonging to Reliance, one of India’s leading conglomerates.85 That same year, Meta signed a $7.5 billion deal with Jio, the country’s largest telecommunications company—owned by Reliance.86 In 2021, Meta opened an office in Gurgaon to train 10 million small businesses and 250,000 creators as part of the government’s plan to digitally transform the Indian economy.87 A year later, Meta-owned WhatsApp collaborated with Reliance’s Jio Mart to launch the first end-to-end shopping experience on WhatsApp.88 WhatsApp also started digital payments in India, a lucrative market that reportedly tops real-time payment transactions in the world.89 Similarly, other tech companies are leveraging India’s rapidly growing digital economy to advance their business interests. Google has made a massive investment in India’s digital infrastructure.90 Musk has discussed making lower-cost Tesla electric vehicles for the Indian market.91 A former tech platform executive pointed out that business opportunities in India such as these may be a factor in content moderation decisions: “Opportunities for expansion in India are immense. There’s still a large user base of rural population that can be signed up for traditional product offerings [on content creation and dissemination, and social networking] while platforms venture into new verticals.”92

Being in the Indian government’s good graces can secure tech platforms’ business interests, for instance, “through digitization schemes that rely on government contracts or indirectly by making the process less bureaucratic.”93 As the same platform executive observed: “In the past two decades, the government has undertaken [public-private-participation] projects in a big way. Platforms can be natural partners for those involving digital infrastructure and services.”94 With the government’s emphasis on “Made in India” enterprises and the ever-present threat of adopting domestic alternatives if global platforms take an adversarial stance, the pressure is only increasing.95 Meta’s former India policy head, Ankhi Das, reportedly told her staff not to endanger Meta’s business prospects in India by citing members of the ruling party for hate speech violations.96 Opportunities for business consolidation and expansion have created high-value stakes for platforms in India where political parties, especially the ruling BJP and its flagship digitization initiative, are major clients who invest in social media outreach.97

In contexts with weak rule of law, governments can also utilize taxation policy to coerce tech companies to comply with their content removal demands. Thailand’s Revenue Code Amendment Act went into effect in September 2021, allowing the government to collect a value-added tax (VAT) from foreign electronic service providers and platforms that receive an annual revenue of more than 1.8 million baht from providing electronic services to non-VAT registered customers in Thailand.98 In paying VAT, foreign tech entities are compelled to register in Thailand, a measure recommended by the junta-appointed National Assembly to Reform the Media to ensure tech companies’ compliance with Thai laws.99 Meanwhile, the domestic tech and media sectors have welcomed this measure as a power-balancing tactic.100

On the surface, the new taxation measure may have little to do with the government’s efforts at content moderation, but it can be exploited to put pressure on platforms that resist the government’s content-related requests. In 2016, Pisit Pao-in, then deputy chairman of the National Assembly to Reform the Media, admitted that companies like Google and LINE did not always accommodate the government’s requests to take down content deemed to threaten national security and the monarchy. But, he explained, tax measures offer the Thai government leverage in their negotiations: “[Platforms’] profit stems from [local] ads . . . The [Thai] state has not collected tax from this revenue . . . I want to discuss this matter with related agencies, especially the Revenue Department. [Taxing foreign corporations] is our leverage to get their support for defending our national security. [If tech corporations accommodate our requests], they may get tax exemption so they can retain the profit.”101

Economic influence is often intertwined with legal influence. For example, during the 2020 anti-establishment protests in Thailand, the MDES threatened Facebook with daily fines for its noncompliance with the government’s demand to remove lèse majesté content. Then, in September 2020, the MDES minister increased pressure on the platform through a new law that could tax social media platforms as over-the-top service providers. Taxation and legal codes such as the CCA would help the MDES deal with “any illicit or fraudulent element,” including content that might offend the monarchy.102 In other words, the Thai government could instrumentalize taxation policy to shape what it considers “a quality platform.”103

Despite these trends, some experts doubt whether the government will ever make good on the threat to weaponize a tax regime.104 Thailand’s bureaucratic bodies, with overlapping mandates, hardly coordinate and at times even compete with one another. Revenue regulations for transnational corporations constitute a bureaucratic area separate from content regulation under the NBTC and MDES. Moreover, politicizing taxation for content censorship could backfire. The Thai private sector primarily relies on social media platforms for e-commerce; any disruptions may prompt pushback against the government by domestic tech startups, e-merchants, and online users. This dependence is largely due to Thailand’s lack of domestic tech industry. In contrast to India, where domestic platforms threaten to supplant global ones, the Thai government has limited economic leverage to force platforms to comply with its content moderation requests.105

The third form of coercive influence is government actors’ use of backdoor connections or personal relationships with domestic or international tech executives to affect content moderation decisions. This political influence is often coupled with economic influence, as personal relationships between platform representatives and government actors based on business interests can lead the former to eschew their own platform’s community guidelines or standards at the latter’s request. Government political influence is also exerted through platforms’ country executives with ties to the governments and pressure from social media users who support the ruling party.

Close links between government elites and platform executives in India can create mutually beneficial relationships. This can be positive, such as when platforms work with government agencies, using their channels to increase people’s awareness of and participation in elections and government programs. The flip side, however, is that platforms can also be politically influenced to bypass their community guidelines for content moderation and to provide or withhold information per government requests.

It has been reported that Meta’s former and current leadership has had close ties to the BJP, leading to concerns about the transparency of the company’s content moderation policies.106 When Meta’s former policy head in India, Ankhi Das, was accused of advising the company to ignore hate speech violations by members of the BJP on Facebook, responses from Meta’s leadership in India were muted. Its Indian business head, Ajit Mohan, refuted the allegation more than a month after the exposé, claiming Das’s policy did not represent that of the company. Following its closed-door meeting with a Parliamentary Standing Committee, Meta did not issue a public statement. Most tellingly, in its first due diligence report on the impact of platform-based hate speech on human rights in India, Meta did not investigate accusations of political bias in its content moderation. Meta claimed that it was studying the report’s recommendations but fell short of committing to implement them.107

The state can also exert influence when individuals with government connections are hired as platform executives. After the 2021 IT Rules in India compelled platforms to appoint local grievance and compliance officers, Twitter appointed Vinay Prakash, who had previously worked for IT minister of state Rajeev Chandrasekhar. Observers expressed concern that such appointments could potentially give the government access to Twitter’s internal discussions and information resources.108

Support from partisan users can also bolster a government’s political influence on content moderation. As active users, these supporters can target platforms through sustained smear campaigns or boycotts. Following Twitter’s confrontation with the government during the 2020–2021 farmers’ protests in India, the company was vilified as a so-called foreign agent that was interfering in the country’s internal affairs. Members of the BJP started actively promoting Koo as a local, more “nationalist” alternative.109 This pressure, in conjunction with the IT Rules, prompted Twitter/X and other platforms to adopt a more conciliatory approach to content moderation. According to a platform executive, companies like Twitter/X feel obligated to strengthen their cooperation with the government and the public to manage pressure from “people who have political support.” This has had a notable impact on platforms’ content moderation practices, as “the cost of compliance may seem less than the cost of non-compliance.”110

Like in India, the intersection between political and economic elites in Thailand provides mutual benefits for both sides. Government elites can ask their business connections for help cracking down on political threats.111 And telecommunications or tech companies can lean on their relationships with political elites to receive lucrative government contracts and even positions in ministries.112

The Thai government often uses the country’s culture of formal and informal so-called talks, which sometimes imply subtle threats, to coerce platforms. This is rooted in patronage-based relationships between the government and domestic tech sectors that intersect with state agencies, such as the Communications Authority of Thailand and the NBTC, or are connected with government figures.113

The political relationships that exist between government figures and local platform representatives in India do not have an exact parallel in Thailand, mainly because platforms there are foreign entities and their representatives are sometimes non–Thai nationals. Despite this, the Thai government has allegedly leveraged official and informal connections with platform representatives to solicit their cooperation in removing unfavorable political content. Though it remains difficult to gauge the extent of these relationships in Thailand, interviewees from tech companies often mentioned that their ability to effectively moderate harmful content circulating online in Thailand depended on ties with Thai state agencies such as the MDES and the police. And research for this paper did reveal evidence of working relationships between the Thai government and platform representatives.

The MDES has collaborated with platforms on a wide range of nonpolitical issues, which possibly allows it to exert influence on political content moderation.114 In 2019, then MDES minister Puttipong Punnakan launched the MDES’s Anti–Fake News Center—viewed by many as the government’s arbiter of truth and a tool to quell the opposition. In early 2020, Puttipong visited Silicon Valley to discuss collaboration with Google and Facebook, especially regarding their role in monitoring “fake” and “inappropriate” content.”115 These meetings may not have led to much substantive collaboration.116 But a similar meeting with LINE Thailand CEO Phichet Rerkpreecha—then head of public policy for the company—led to LINE endorsing the MDES’s crackdown on so-called fake news.117 Between 2004 and 2008, Puttipong and Phichet worked together as the spokesperson (and in 2006 as a deputy) and assistant, respectively, of former Bangkok governor Apirak Kosayothin.118 LINE’s collaboration with MDES reinforced the perception that its CEO and the former minister were good friends.

Initial attempts to establish a channel of communication between platforms and the Thai government for content removal can be traced back to 2013 and 2014, when first the civilian government and then the subsequent military junta asked LINE to assist them with “obtaining communications of Thai citizens.”119 In 2015, Pisit—a former cybercrime police officer and then vice president of the junta-appointed Reform Commission on Mass Communication—gathered representatives from Google, Facebook, and LINE for a so-called talk, to ensure these foreign entities understood what kind of content was unacceptable under Thai laws and traditions. Pisit asserted that the reason for their noncooperation was the lack of communication as well as legal and cultural misunderstandings, saying “what [Thais] think is wrong may not be wrong for [these foreign companies] so content removal based on Article 112 is difficult . . . They may criticize their leaders freely because these are public figures, but in Thailand, such is unacceptable for Thais.120

The death of King Rama IX in 2016 gave the Thai government pretext to request cooperation from tech companies. The NBTC issued an order for local ISPs and social media companies to monitor inappropriate content. In response, Facebook executives allegedly sent two letters to the MDES saying that, after careful legal review, they were willing to collaborate with Thai authorities to restrict content that was illegal under local law.121 The MDES, the cyber crime police, and the NBTC held a meeting with tech companies—including LINE, Google, and possibly Meta—at the Government House in October to “seek cooperation from social media [companies] in suppressing lèse majesté content during the mourning period.”122 LINE appears to have been most willing to collaborate, proposing that its headquarters in Japan would set up a steering committee to investigate reports of lèse majesté content. Google also reportedly blocked lèse majesté webpages after the meeting.123

Backdoor communications between the Thai government and Facebook also appear to have played a role in the aforementioned Royalist Marketplace incident in 2020. A Thai media CEO and sources from tech outfits in Thailand cited a meeting between Facebook and government representatives that took place in California the same year. The CEO went so far as to speculate that a palace aide might have made this meeting possible by exploiting Facebook’s community guidelines on local laws to pressure the company.124 A source who used to work for Facebook/Meta, however, mentioned that the palace, via the MDES, applied pressure on the company in 2021—not in 2020—when anti-establishment protests were conflated with nationwide criticism of the king’s involvement in the delayed coronavirus vaccine rollout.125

Finally, in January 2024, Meta appointed a former Royal Thai Police officer as its new public policy head in Thailand. Given the Thai police’s negative reputation, dissidents are concerned that this new appointment could result in greater online censorship and cooperation with the Thai authorities at the expense of freedom of expression.126

Despite governments’ attempts to influence platforms, our research shows that their efforts may not always yield the intended outcome. Sometimes, platforms push back; at other times, they readily comply.

Before August 2020, Meta reportedly stalled when the Thai government ordered it to take down the Royalist Marketplace Facebook group. When the company eventually complied, it immediately issued a statement condemning government requests that “[are] severe, contravene international human rights law and have a chilling effect on people’s ability to express themselves.” The company claimed it was planning to legally challenge the Thai government. Although it was unclear whether Meta could realistically do so, the news of it possibly suing the Thai government became an international sensation and contributed to the Thai authorities’ retreat.127 In the end, the government did not pursue its lawsuits against Meta, and Meta had no grounds to countersue.128

The same cannot be said for India, where platforms are increasingly acceding to the government’s demands to take down content or accounts. As discussed, Meta and now X have begun to globally, not just locally, block content at the Indian government’s behest, which allows the government to flex its powers beyond its territory. X’s owner, Musk, has made the platform’s reluctance to lock horns with the government clear. He noted that social media rules in India were “quite strict,” and that he would rather comply with the government’s requests than risk sending X employees to jail.129

Three structural factors explain why tech companies have responded differently to the Thai and Indian governments.

The first is whether the platforms consider a country to be an important economic market. As tech companies expand into adjoining ventures, they have opened the door for the government to use political content moderation as a bargaining chip. Google and Meta increased their rate of compliance with government requests as they experienced a period of business consolidation and searched for ways to diversify their revenue beyond ads. As Mohan, Meta’s Indian business head, remarked, “India is in the middle of a very exciting economic and social transformation . . . The pace of this transformation probably has no parallel in either human history or even in the digital transformation happening in countries around the world.”130 Similarly, Google CEO Sundar Pichai responded positively when MeitY Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw encouraged collaborative partnerships between the Indian government and tech platforms, saying that India offers an “incredible opportunity” for tech startups, unified payments interface systems, and artificial intelligence.131 Tesla officials visited India in 2023 to discuss setting up an electric vehicle factory for domestic sale and export.132

In contrast, the Thai government is much more economically dependent on tech companies. Under government pressure in 2022, Meta threatened to exit the country instead of backing down. While it ultimately agreed to remove the Royalist Marketplace Facebook group, it threatened to close its office in Thailand if the government asked it to take down a new Royalist Marketplace page. This made the Thai e-business sector nervous, which reined in the regime’s hardline stance.133 Because Thailand remains a small-to-medium-sized market, Meta was emboldened to prioritize the principle of protecting freedom of expression over profit in the face of government pressure.134

The second factor is the growth of domestic platform companies. In India, Koo, with its emphasis on connecting local communities in local languages, was touted as a “Made in India” platform that could also be downloaded from the Government of India’s app store. Other homegrown social networking apps that incorporate localized features and are user-friendly —like JioChat (of Reliance Industries Ltd.) and ShareChat—demonstrate potential. While these local platforms are not rivals to Big Tech, they have the potential to become competitive—especially if they are promoted by the government.

In comparison, there are virtually no domestic Thai companies to compete with international platforms. Tech startups in the country got off to a late start. Most tech firms are either subsidiaries of foreign corporations focused on e-commerce and delivery service (e.g., Singapore’s Shopee and Grab or Japan’s LINE) or telecommunications (e.g., China’s Huawei). For the most part, locally owned tech companies focus on agricultural tech, green energy, and household services.135 At present, none of the top Thai tech startups are communications or networking platforms.136

The third factor is whether tech companies can fend off legal coercion. Meta, for instance, insisted that the Thai government needed a court order to compel the platform to take down or geo-block content prohibited under lèse majesté law. This time-consuming process often frustrates the authorities, and the posts remain publicly accessible as they acquire a court order. Moreover, platforms can deliberately inform account owners targeted by the authorities about the pending action against their posts. This gives the account owners time to respond. When the government sought to geo-block the Royalist Marketplace, Meta’s regional staff warned the group’s administrator, Pavin, about the imminent block.137 Pavin had enough time to create a new page and invite his followers to join it. The government’s efforts backfired, as the new page doubled the Royalist Marketplace’s following from one to two million.

Similarly, X has informed some dissidents about the government’s pending legal actions against their posts, suggesting they seek legal support. According to Andrew McGregor Marshall, an outspoken critic of the monarchy, “before [my posts would be blocked upon the Thai authorities’ requests], Facebook and Twitter would inform account owners . . . it’s quite clever, making it pointless to geo-block because I can repost it and then [the authorities] have to get the court order again [for content removal].”138

While international platforms have effectively contested the Thai government’s legal threats, they have not enjoyed the same success in India.139 Tech companies in India perceive noncompliance to have serious consequences for their operations. In interviews, platform representatives referred to the legal legitimacy of government requests as the basis for their compliance. According to one representative, “we follow the law of the land because it makes logical sense. If a legitimate request is made, that is, the government agency has met all the legal criteria, we will give data or block content. If they don’t, we will push back.”140

Unlike in Thailand, where the government needs a court order to request content be taken down, government agencies in India have requested content removal under the Indian Penal Code, the Criminal Procedure Code, the IT Laws, and the IT Rules. At times, platforms may push back—for example, asking the authorities to “get an order from the designated body under MeitY to issue that order of takedown or seek post facto judicial review of takedown decision.”141

Meta’s WhatsApp has filed a plea challenging the “traceability” clause of the IT Rules in the Delhi High Court, which gives authorities the ability to determine the first originator of a message. The court has stayed the implementation of this rule pending further hearings. If WhatsApp prevails, it would be a significant victory against the government.142 However, the legal scope may shrink if the government invokes emergency provisions under the IT Rules and the IT Act.143 In early 2023, the government used emergency powers to force all major platforms to block links to a controversial documentary about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.144 If platforms in India fully accept those provisions of the IT Rules, the government would become, in effect, the final arbiter of online political content.

The typology of influence set out in this paper can inform regulatory policies to preempt the chances of coercion. Emerging markets have become crucial for growth-focused platforms. In the case of India, existing dependencies are exacerbated when the government is a major client of a social media platform. This cycle of dependency is further perpetuated when platforms wish to expand their operations beyond social media and messaging services to tech sectors where the government is again their facilitator and client. This may make platforms more prone to government control, impacting their content moderation policies. Even when there are remedial measures in the case of government overreach, platforms seem to prefer compliance over confrontation unless their business model is directly targeted.

In the absence of formal legal obligations, platforms may respond to social expectations by acknowledging rights-based approaches to content moderation, as their decisions have an impact on democratic discourse at scale.145 Pressure from civil society advocates can increase the reputational costs for platforms if companies cave to government coercion. Concurrently, users can also collaborate with civil society advocates to challenge platforms’ arbitrary rules. This can prompt those companies, which build their brand value on their users’ right to free expression, to change or modify certain policies. Concerned civil society organizations can mobilize on strategic issues like protecting user data and preventing government fact-checkers from having the final say on whether content is acceptable.

Similarly, platforms can also band together to challenge autocratic coercion by pooling their strengths. Joint actions by tech companies can minimize the risk of a single platform being targeted by a government. Civil society advocates have campaigned to strengthen legal remedies against government coercion. Tech companies can add their collective weight to legal reform campaigns to ensure that regulation does not turn into a tool of repression.

Janjira Sombatpoonsiri

Research Fellow, German Institute for Global and Area Studies

Janjira Sombatpoonsiri is a research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies and an assistant professor at Thailand's Chulalongkorn University. Her current research focuses on autocratic weaponization of disinformation laws, digital propaganda and conflict narratives in Southeast Asia, and digital repression of protest movements. Her academic articles appear in, for instance, International Journal of Communication, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Voluntas, and Journal of Peace Research. She is a regional manager for the Digital Society Project.

Sangeeta Mahapatra

Sangeeta Mahapatra is a research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, Hamburg. Her areas of research include examining the nature, trends, and impacts of digital authoritarianism and disinformation on democracy and diplomacy in South and Southeast Asia; the shaping of ethical and effective norms and frameworks of global internet and AI governance; and building cyber resilience against emergent security threats.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

A new Carnegie survey of Indian Americans examines shifting vote preferences, growing political ambivalence, and rising concerns about discrimination amid U.S. policy changes and geopolitical uncertainty.

Milan Vaishnav, Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, …

The India AI Impact Summit offers a timely opportunity to experiment with and formalize new models of cooperation.

Lakshmee Sharma, Jane Munga

An exploration into how India and Pakistan have perceived each other’s manipulations, or lack thereof, of their nuclear arsenals.

Rakesh Sood

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum