Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

Providing and financing international public goods to cope with the global challenges in a fractured global order will require bold and innovative approaches.

This essay is part of a series of articles, edited by Stewart Patrick, emerging from the Carnegie Working Group on Reimagining Global Economic Governance.

We are now living in a paradoxical fractured global order, characterized by the simultaneous integration and divisions among countries and among peoples within countries. This order benefits a small percentage of humanity at the expense of the vast majority, resulting in a world of widespread poverty and inequality. Meanwhile, a host of complex challenges that transcend national boundaries and threaten the human condition has also emerged, among them climate change, pandemic disease, financial instability, violent interstate conflict, transnational crime, and biodiversity loss. Although many of these problems have deep historical roots, their reach has expanded and their impact has become more ominous. Advances in science, technology, and knowledge are creating extraordinary opportunities for progress, but these capabilities are unevenly distributed and highly concentrated, and they carry inherent risks.

Crafting effective responses to these multiple challenges will require collective action at a scale never seen before, except perhaps after World War II when the modern multilateral system emerged. A convergence of wills, concerted decisions, and agreed interventions by myriad individuals and groups across the globe will be necessary to forestall the worst consequences of the combined impact of these challenges and the perils they entail. The centerpiece of this effort should be the creation of a robust new multilateral framework to deliver “international public goods,” backed by a new global tax on financial transactions.

The concept of public goods provides a helpful framework to understand collective initiatives to meet common challenges.1 The defining attributes of a public good are nonexcludability, nonrivalry, and positive externalities. These terms imply, respectively, that others cannot be excluded from using the same good, that the use of the good does not exhaust its supply, and that the provision of public goods creates broadly shared benefits. Although the concept of public goods initially was applied to the national level, in the past two decades it has been projected into the international arena in the form of international development cooperation, a potentially promising institutional approach to managing transnational challenges in a mutually beneficial manner.

The public goods lens is particularly appropriate to understanding the fractured global order and the ways in which actions at different levels, from international to local, can help address global problems. The world today is beset by a slew of problems that might be thought of as “international public bads.” Many individual decisions—regarding fossil fuel use, consumption patterns, agricultural practices, industrial production, transport of goods and persons, conflict resolution, and financial speculation, among others—generate negative consequences, including greenhouse gases, deforestation, biodiversity loss, geopolitical instability, financial crisis, excessive waste, and deepening inequalities. These “international public bads” must be prevented or avoided through the provision of their opposites: international public goods. Limiting the occurrence and forestalling the negative impacts of global bads will require the widespread adoption of measures to prompt behavioral changes at all levels of society, from supranational decisions to national and regional policies to individual decisions in specific localities.

The components of what may be called an “international public goods delivery system” should cover this spectrum of social organization. First, there is a need for extensive public awareness about the desirability of an international public good and political agreement on joint initiatives to provide it. This consensus should lead to binding instruments (conventions, treaties, and protocols) implemented by international institutions acting as intermediaries to promote, organize, finance, manage, monitor, enforce, and evaluate measures aimed at providing the international public good. Second, any system created to deliver international public goods must have robust financing mechanisms to support the national and local organizations that design and implement policies, develop operational procedures, and engage with agents in specific locations to induce decisions and behaviors contributing to the provision of the international public good.

It is clear that initiatives to provide international public goods will take time to bear fruit. As the case of reducing carbon emissions to mitigate climate change shows, it can take decades to reach even nonbinding multilateral agreements. According to the renowned scientist Vaclav Smil,

Dealing with [the climate change] challenge will, for the first time in history, require a truly global, as well as a very substantial and prolonged, commitment. . . . The [United Nations’] first climate conference took place in 1992, and in the intervening decades we have had a series of global meeting and countless assessments and studies—but nearly three decades later there is still no binding international agreement to moderate the annual emissions of greenhouse gases and no prospect for its early adoption.

Moreover, even if the binding climate agreements were in place, it likely would take a long time for local decisions taken under their provisions to have a discernible global effect. Nevertheless, postponing decisions to prevent irreversible shifts in the planet’s climate increases the likelihood of catastrophic consequences sooner rather than later. Innovative financing options might help surmount such obstacles to progress on climate change—and other shared global challenges.

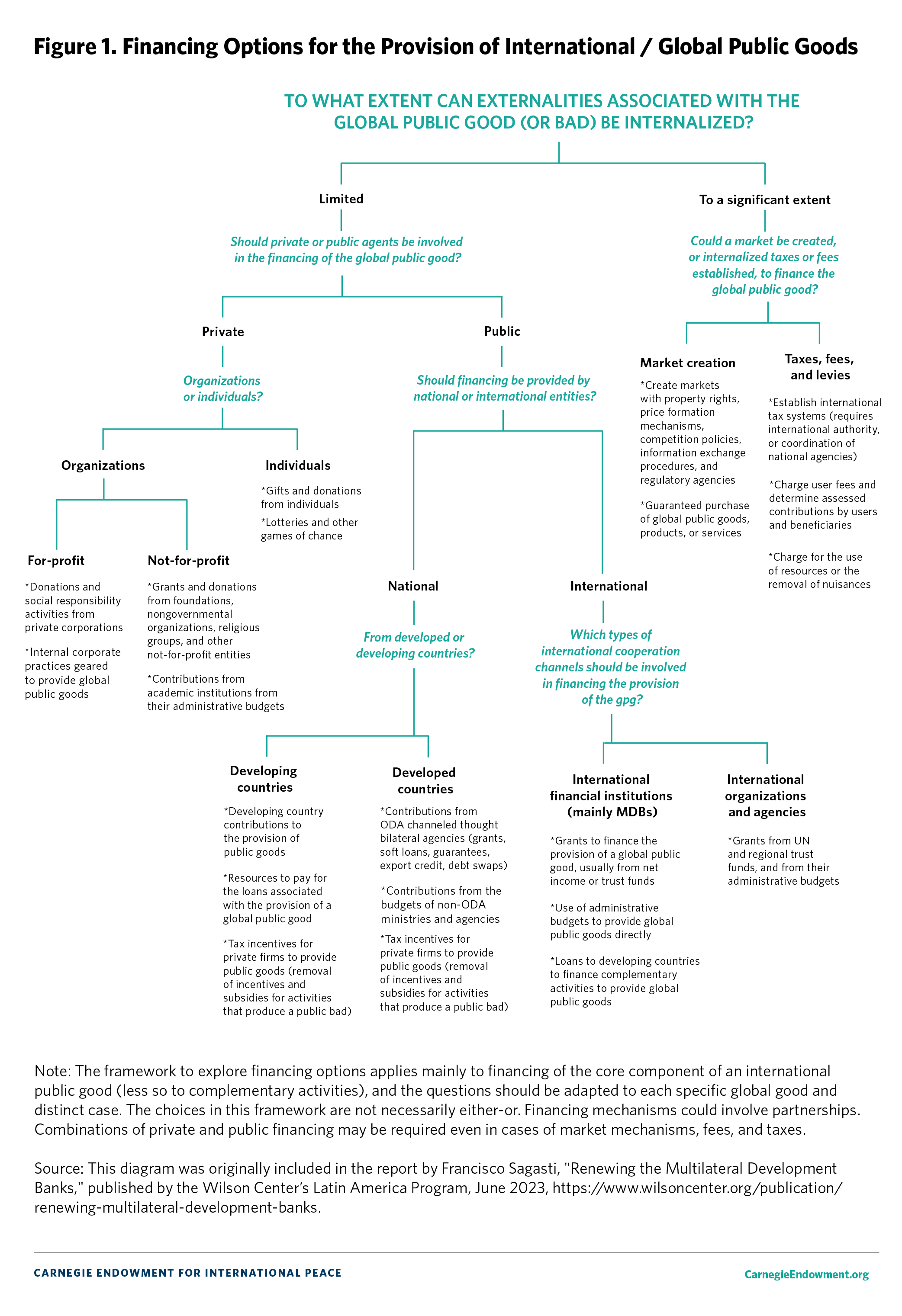

Several financing options can support the provision of international public goods. These range from market creation, taxes, and levies at one end of the spectrum to public budget allocations and private donations at the other (see Figure 1). In the present constrained financial environment of most middle- and low-income countries, it is difficult to expect significant public budget allocations for the provision of international public goods. In addition, the geopolitical and military conflicts and tensions of the fractured global order have led several high- and upper-middle-income countries to reallocate resources toward defense, to the detriment of other areas and particularly international cooperation.

Therefore, it would make more sense to finance the provision of international public goods through market creation or some form of international taxation. This approach would allow revenues to be collected automatically and continuously, and to be allocated in a more predictable way. The successes and failures of market creation mechanisms have been highlighted in the emissions trading schemes that have been in operation for some time in Europe, and they reveal such mechanisms to be of limited effectiveness. Therefore, a sensible financing option would be to opt for some kind of international tax and then create special arrangements to collect, allocate, and administer its proceeds.

Comparable proposals have been made for other purposes, including James Tobin’s tax on short-term currency movements to discourage speculation and the tax on airline tickets for development finance suggested in 2005 by France’s then president Jacques Chirac. The latter idea received support from nongovernmental organizations, as well as Chile and the United Kingdom among other countries. Similarly, though not related to development goals or international public goods, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries recently reached agreement on a global minimum tax of 15 percent on multinational corporations, which is planned to become effective in 2024. The economist Thomas Piketty has also suggested a global wealth tax, generating considerable debate but little political traction.

A recent initiative, which could be implemented in the near future, involves a tax on international shipping aimed at curbing greenhouse gases. Under this proposal, endorsed by the International Maritime Organization, shipping companies would pay a fee for the carbon they release into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. The amounts raised would reach billions of dollars annually and be directed to decarbonize the shipping industry. The details regarding fee levels, collection schemes, trading mechanisms, and allocation and administrative arrangements still need to be ironed out, but negotiations on these issues seem to be on track.

Another promising scheme for the provision and financing of international public goods and development is a proposed international financial transactions tax (IFTT). Estimates suggest that a small tax of 0.1 percent could generate tens, and conceivably hundreds, of billions of dollars. Scores of economists and policymakers, as well as prominent political leaders, have endorsed the idea, which could be implemented without great difficulty because international financial transactions are now reasonably well tracked, in contrast with what would be required for wealth taxes. In addition, an IFTT would raise significant resources and have a negligible negative impact on economic activity. According to Professor Mariana Mazzucato of University College London:

Financial transaction taxes (FTT) have a proven record as effective policy tools worldwide. Roughly forty countries, including powerhouses like Japan, Germany, Italy, France, China, Brazil, India, South Africa, Chile and the UK, either currently utilize this form of tax or have recently done so. The United States already maintains a minor transactions tax.

If significant levels of financing for international public goods are to be raised in the not-to-distant future, an IFTT will likely figure as a major source of funds. For convenience, any such tax should be accompanied by an international public goods facility to collect, allocate, and manage the funds obtained from the tax and from other sources. Before such a tax became operational, governments also would need to agree on the details of its institutional governance, including issues of its administration, operations, allocation and disbursement, and monitoring and evaluation.

In the current geopolitical climate, an IFTT is unlikely to become a truly global initiative, at least in the short term. However, it may be possible to create narrower multilateral coalitions for specific purposes, composed of likeminded countries, that show how an IFTT could work in practice and chart a course for more ambitious proposals. Exchanges on such initiatives may take advantage of existing multilateral arrangements, in particular involving the United Nations, regional organizations, and specialized agencies, and also in issue-specific organizations, as in the case of the International Maritime Organization.

Arrangements will need to be made to determine which international public goods to fund, as well as the range of financing instruments (for example, grants, regular and soft loans, guarantees, equity, and blended finance) that should be made available. Other key decisions would be whether to calculate and collect any such IFTT at the origin or destination of the transaction, and where to deposit the collected amounts. Institutions such as SWIFT could facilitate these tasks and should be involved in negotiations to create an IFTT. The Bank for International Settlements also could help establish a special account where the proceeds of the tax would be deposited, held, invested, and transferred to an IFTT Secretariat.

The operational and administrative arrangements for allocating and disbursing the resources obtained through an IFTT could be handled by a secretariat composed of staff seconded by the multilateral development banks (MDBs), many of which (most notably the World Bank) now have as a mandate the provision of international public goods. In addition to seconding staff, the MDBs could support the secretariat with contributions from their net incomes. To avoid potential conflicts of interest, the head of an IFTT Secretariat would be appointed by its governing board but not be on the staff of any of the MDBs involved.

Providing and financing international public goods to cope with the global challenges that are now clearly visible in a fractured global order will require bold and innovative approaches. The creation of an international public goods facility funded by an IFTT is a promising approach to support the range of initiatives and local actions required for their provision. Nonetheless, it will take a long time and a strong sense of urgency in response to climate change and other major common challenges, together with an unusual degree of political generosity, commitment, and determined efforts by key political leaders, for this change to happen. It likely will start in a modest way and grow as its benefits become more apparent, but there is no time to lose.

1 The terms “global” and “international” have both been used to refer to supranational public goods. This piece uses “international” to envisage a gradual process toward such goods becoming truly global.

Dr. Francisco Sagasti

Dr. Francisco Sagasti is a professor at the Pacífico Business School in Lima, Peru, and a senior affiliated researcher at the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. He has been president of Peru, a congressman, the head of his parliamentary caucus, and the chairperson of the Science and Technology Committee.

Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

The recent record of citizen uprisings in autocracies spells caution for the hope that a new wave of Iranian protests may break the regime’s hold on power.

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

Internet service providers can facilitate internet access but also draconian control.

Irene Poetranto

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy