Saheb Singh Chadha

Source: Getty

Negotiating the India-China Standoff: 2020–2024

India and China have been engaged in a standoff at their border in eastern Ladakh since April–May 2020. Over 100,000 troops remain deployed on both sides, and rebuilding political trust will take time.

Note: The analyses presented in this paper are based on developments up to December 3, 2024.

Summary

In February 2024, India’s defense secretary, Giridhar Aramane, termed China a “bully.”1 The defense secretary may not have been speaking in an official capacity and articulating the view of the Government of India. Nevertheless, the remark was significant as it was on the record and by an Indian policymaker at the strategic level of decisionmaking. While unusual, it reflects the reality of India-China ties over the past four years. Both sides have been engaged in a standoff at their border in eastern Ladakh since April–May 2020. Over 100,000 troops remain deployed on both sides, and rebuilding political trust will take time.2

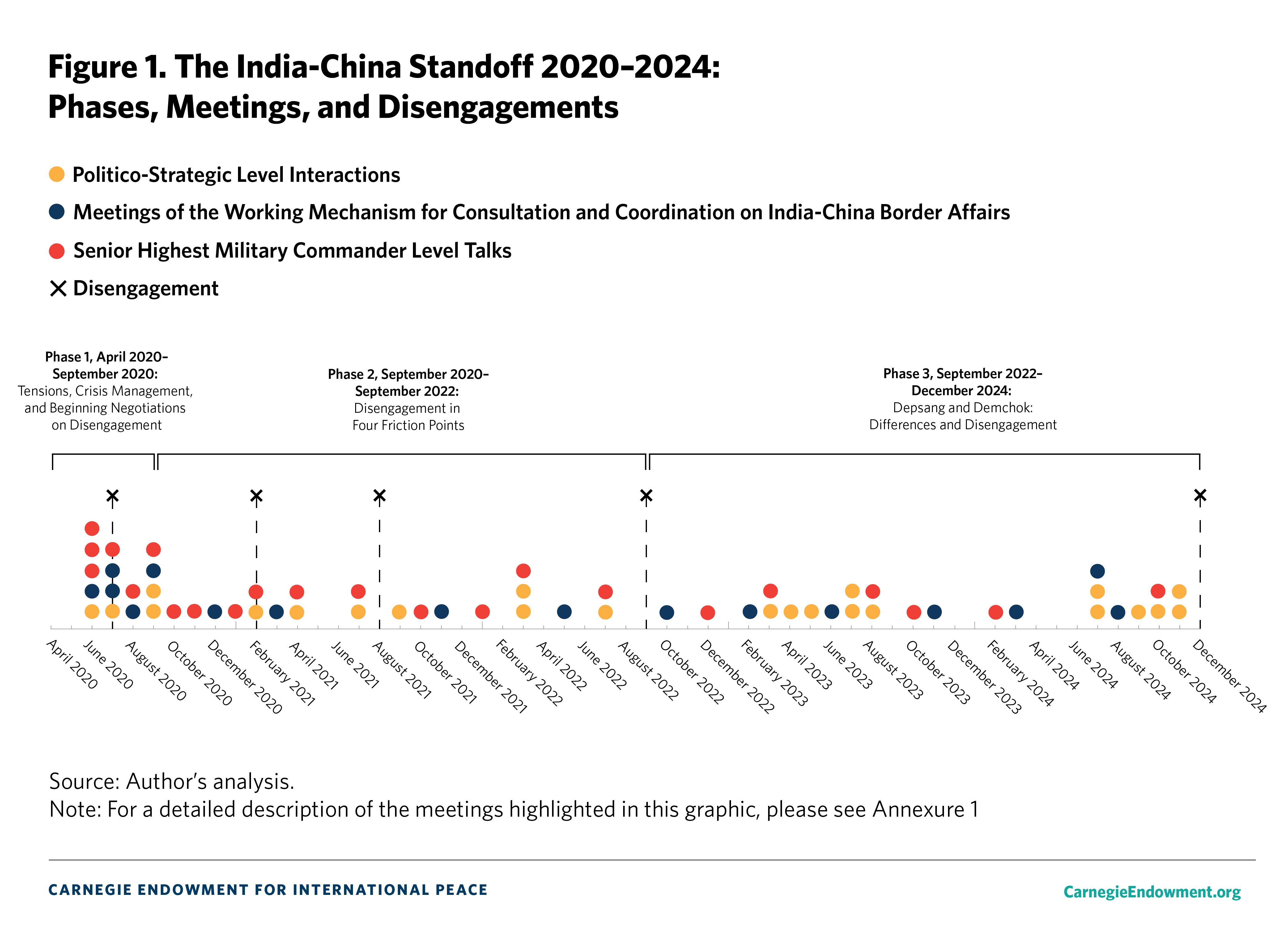

This paper argues that it is possible to divide the past four years of the standoff into three phases based on the negotiating positions of both sides. Between April and September 2020, both sides sought to manage the crisis, reduce tensions, and avoid a fatal clash akin to the Galwan incident. Between September 2020 and September 2022, both sides negotiated disengagement in four friction points in eastern Ladakh. Between September 2022 and July 2024, the gaps in their positions were visible. China signaled its unwillingness to disengage in Depsang and Demchok, preferring to treat them as legacy issues and wanting both sides to “turn over a new leaf” for the border situation.3 It wanted the broader bilateral relationship to expand. India stood by its demand for complete disengagement and de-escalation of troops, and restoration of patrolling rights in Depsang and Demchok before broader bilateral exchanges could deepen. The two sides have attempted to find consensus since July 2024 and, as a result, the situation underwent a change from October to December 2024. Both sides came to an agreement on patrolling in Depsang and Demchok in October, followed by an announcement by India’s external affairs minister (EAM) S. Jaishankar in December, that disengagement had been “achieved in full,” and broader bilateral exchanges were being discussed.4

This analysis is based on four types of sources. The first type includes official statements resulting from the conversations held between India and China since June 2020 to resolve the standoff. These conversations are held through three channels—the Senior Highest Military Commander Level (SHMCL) talks, the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC) at the diplomatic level, and the meetings at the politico-strategic level between heads of state, foreign ministers, defense ministers, national security advisors, and special representatives on the India-China boundary question. The second category entails other official statements by representatives of governments of both countries. The third type includes interviews with stakeholders in the Government of India who have been involved in negotiations and decisionmaking on the standoff or have knowledge of India-China military dynamics along the border, and the fourth category is media reports. This paper corroborates these sources to develop an understanding of the past and present positions of both countries on the standoff and the dialogue that has taken place between India and China over the past four years. The utility of this analysis can be attributed to the paucity of information from official statements on both sides, particularly the Chinese side.

The analysis sheds light on periods of progress within a broader four-year low in the relationship and the factors facilitating that progress. It reveals the role of meetings at the politico-strategic level in facilitating progress in negotiations and investigates why China has sought to coerce India at their land border. It concludes that one of the primary reasons is that China sees India’s infrastructure build-up on its border as part of a plan by the United States to contain China in Asia. In lieu of the agreement on patrolling reached on October 21, 2024, and the bilateral meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping thereafter, the paper recommends continued dialogue between India and China at the politico-strategic level. This increases the possibility of both sides resolving the standoff and provides an opportunity to bridge the trust deficit between the two countries.

Introduction

In April 2020, a standoff commenced between India and China when the latter diverted its troops from an exercise in Tibet to near the border with India.5 These troops then proceeded to move toward the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh and also “sought to change the status quo” in several locations.6 The Indian side maintained that these actions by China were “in complete disregard of all mutually agreed norms,” and reciprocated with the induction of forces to the border in eastern Ladakh.7 The crisis reached a tipping point when troops clashed in the Galwan Valley on the night of June 15, leading to the first fatalities on the India-China border since 1975. India’s EAM, S. Jaishankar, stated at the time that the “unprecedented development will have a serious impact on the bilateral relationship.”8

The past four years have been characterized by tensions between the two nuclear-armed neighbors and the substantial augmentation of troops and equipment on their shared border. The period has also seen clashes that carry the risk of escalation, such as in Galwan in June 2020 and Yangtse in December 2022.9 This paper argues that it is possible to divide the past four years of the standoff into three phases based on the negotiating positions of both sides. Between April and September 2020, both sides sought to manage the crisis, reduce tensions, and avoid a clash akin to the Galwan incident. Between September 2020 and September 2022, both sides negotiated disengagement in four friction points in eastern Ladakh. These were Patrol Point (PP)-15, PP-17, and PP-17A in the Gogra-Hot Springs area, and the northern and southern banks of Pangong Tso.10 After September 2022, the gaps in the two sides’ positions widened. China signaled unwillingness to disengage in the two remaining friction points—Depsang and Demchok. It wanted both sides to move past the border standoff and for the broader bilateral relationship to continue unencumbered. India doubled down on its demand for complete disengagement and de-escalation of troops before broader bilateral exchanges could deepen. In October 2024, both sides came to an agreement on patrolling in Depsang and Demchok.11 In December 2024, it was announced that disengagement had been “achieved in full,” and broader bilateral exchanges were being discussed.12

This paper proceeds in three parts.

Part I introduces the channels of negotiation between the two sides on the standoff, the methodology for the paper, and the existing literature on the standoff.

Part II studies the positions of both sides on the standoff in three phases:

- Phase 1: April 2020–September 2020

- Phase 2: September 2020–September 2022

- Phase 3: September 2022–December 2024

Part III presents the takeaways that have emerged from the analysis, investigates why China has sought to coerce India at their shared border, and provides policy prescriptions.

Part I: Channels of Negotiation, Methodology, and Literature Review

Channels of Negotiation Between India and China

Since June 2020, India and China have negotiated on the standoff primarily through three channels. Their hierarchy is explained first, followed by a description of each mechanism.

The first channel is the meetings at the politico-strategic level between the heads of states, external affairs ministers, defense ministers, and national security advisors. Second is the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC), which is a working group of diplomatic and military experts on both sides. Third is the Senior Highest Military Commander Level (SHMCL) talks at the military level. A stakeholder at the strategic level of decisionmaking further explained the hierarchy and roles of each mechanism to the author.13 The politico-strategic level meetings set out the framework; the WMCC meetings detail the steps to be taken; and the military commanders discuss and implement these steps on the ground. EAM Jaishankar referenced these mechanisms as channels of negotiation with China: “I think the main mechanisms, we have a mechanism called WMCC, and we have a mechanism called Senior High Level Commander’s Meeting. One, you know, one is a kind of military-led with MEA in it, the other is MEA-led with military in it. These mechanisms continue to do the work,” and “obviously you have to have a leadership level by it.”14 India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) too notes that “since June 2020, the two sides have engaged in discussions through WMCC and Senior Commander’s Meeting (SCM) for disengagement in the border areas along the LAC in Eastern Ladakh.”15

Meetings at the politico-strategic level include interactions between representatives such as the two sides’ foreign ministers. With the exception of the bilateral working visit of China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, to New Delhi in March 2022, interactions at this level have taken place primarily on the sidelines of multilateral summits or through telephonic conversations. Fourteen interactions have taken place between EAM Jaishankar and China’s foreign ministers Wang Yi (2013–22, 2023–present) and Qin Gang (2022–23). Three interactions have taken place between India’s defense minister, Rajnath Singh, and China’s ministers of national defense Dong Jun (2023-present), Wei Fenghe (2018–23) and Li Shangfu (2023). Four interactions have taken place between National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval and his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, with one interaction in their role as Special Representatives on the India-China boundary question. The state leaders, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping, have had three interactions—at the G20 Summit in November 2022, at the BRICS summit in August 2023, and a bilateral meeting on the margins of the BRICS summit in October 2024.16

The WMCC predates the 2020 standoff, having been established in 2012 through the India-China Agreement on the Establishment of a Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs.17 It is mandated to “deal with important border affairs related to maintaining peace and tranquility in the India-China border areas” and “will address issues and situations that may arise in the border areas that affect the maintenance of peace and tranquillity.” The Indian side is headed by the joint secretary in the East Asia division of the MEA and the Chinese side by the director-general of the Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). The WMCC has met thirty-one times till date. Fourteen of these meetings had taken place before the 2020 standoff, with the last one held before the 2020 standoff in July 2019.18 Seventeen meetings have taken place since the standoff began, with the first one after the standoff began (the fifteenth overall) taking place on June 24, 2020.19 The WMCC last met on August 29, 2024.20 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the fifteenth to twenty-fifth meetings took place virtually.

The SHMCL talks, better known as the corps commander talks, are held between the two sides’ senior highest military commanders (SHMCs) who are responsible for eastern Ladakh. On the Indian side, the talks are led by the general officer commanding-corps of the Indian Army’s XIV Corps based at Leh, in the union territory of Ladakh.21 On the Chinese side, they are led by the commander of the South Xinjiang Military District, part of the People’s Liberation Army’s Western Theater Command.22 Prior to the standoff, the senior highest military commanders of both sides had not met, with meetings taking place at the brigade commander– or division commander–level.23 After the tensions in May 2020 were not able to resolve through talks below the SHMCL, the Chinese side suggested that the senior highest military commanders meet, which was subsequently taken up.24 Thus, the first SHMCL talks took place on June 6, 2020.25 The meetings began with the purpose of managing tensions, thereafter evolving to discuss the granularities around disengagement. According to statements by the Government of India, twenty-one rounds of SHMCL talks have taken place so far, with the most recent one on February 19, 2024.26 On the Indian side, each meeting of the corps commanders is preceded by a meeting of India’s China Study Group, which lays out the minimum and maximum that the corps commander can negotiate.27 The corps commanders meet at the Border Personnel Meeting points in eastern Ladakh, either at Chushul on the Indian side or Moldo on the Chinese side.

The public official statements resulting from these three channels of communication are relevant, unique, and worthwhile of analysis for several reasons.28 They are credible, primary sources that are publicly accessible and available across the entire duration of the standoff. They provide details of the conversations taking place between the two sides and the negotiating positions they take.29 They are also relevant because both sides have at times released separate statements from the same meeting, indicating differences. Overall, placing both sides’ statements in comparison with each other reveals how their positions have evolved over time and when they have differed with each other and on what issues. In the absence of other primary sources, this analysis is especially important. What emerges is the story of the back-and-forth dialogue that has taken place between India and China over the past four and a half years regarding the border standoff and their broader bilateral relationship.

Methodology

For this paper, a mixed-methods approach was adopted with an analysis of textual sources, corroborated by stakeholder interviews.

The textual sources from the Government of India include the official statements from the three channels of negotiation as well as any separate statements from the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and Ministry of Defence (MoD), along with any other public statements by government representatives. On the Chinese government’s side, there are the official statements from the three channels of negotiation, any separate statements by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), Ministry of National Defense (MND), or any other public statements by government representatives. Where a conversation took place between the two sides, the statements were placed side by side, with the following angles of inquiry.

- The positions that the two sides adopted on any substantive questions, such as those of disengagement, de-escalation, peace and tranquility in the border areas, and broader India-China relations.

- The similarities or differences in positions and considering whether both sides issued a joint statement or separate statements, with joint statements indicating a degree of consensus and separate statements indicating differences.

- The tone and tenor of the statements, for example, the adjectives being used in the statements to describe the conversations.

- The duration between two rounds of meetings, which reflect the momentum of negotiations, or the lack of it.

- The interplay of all of the above factors.

Analyzing official statements using the aforementioned methods generated a set of preliminary takeaways. These were then tested in meetings with relevant Indian stakeholders who nuanced, complicated, reinforced, and pushed back on the analysis. The stakeholders included senior, retired, or serving officials from the primary bodies in charge of policymaking and negotiating the standoff. These included the Indian Army, MEA, MoD, and the National Security Council Secretariat. Consultations with Chinese policymakers are beyond the ambit of this research paper and were logistically infeasible. Thus, the understanding of the Chinese position is brought out by corroborating Chinese statements with the views of Indian policymakers on Chinese thinking, rather than those of Chinese policymakers.

Literature Review

Work on the 2020 India-China standoff is diverse. There are long- and short-form works exploring different aspects of the standoff, such as China’s goals behind its actions in April–May 2020, military dynamics and border infrastructure, policy options for both countries, and comparisons between past and present standoffs.30 There are also works by diplomat-scholars that touch upon the present standoff and Chinese behavior along the LAC over the past decade.31

However, there is a gap in the literature in terms of works that explore the negotiating positions of both sides across the four years of the standoff.32 Even fewer works compare official statements across time and between the two countries. Analysis of Chinese statements and sources is particularly rare.33 It is worth mentioning that the standoff is a relatively recent development, hence analyses have only recently begun to be published.

Part II: Detailing the Standoff

Based on the negotiating positions both sides have adopted, it is possible to divide the standoff into three chronological phases. A brief description of the three phases is placed below, followed by a paraphrasing of India and China’s negotiating positions in the course of the standoff. This is followed by details of each phase, describing both sides’ positions in the meetings across the three channels of negotiation. The details of each phase of the standoff form the major part of this paper.

- Phase 1, April 2020–September 2020: This was characterized by both sides holding each other responsible for the border tensions, managing eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation, and the fallout of the Galwan incident.

- Phase 2, September 2020–September 2022: In this phase, both sides sought common ground, agreed to a degree on the way forward, and negotiated disengagement in four friction points.

- Phase 3, September 2022–December 2024: Both sides adopted increasingly divergent and hardened postures on the standoff from September 2022 until mid-2024 and disagreed on the way forward for the standoff and the bilateral relationship. This situation changed between July and December 2024, with both sides coming to an agreement in October on patrolling in Depsang and Demchok. In December, it was announced that disengagement had been “achieved in full,” and broader bilateral exchanges were being discussed.34

The government of India has maintained and communicated one basic position throughout the standoff. It is that India desires disengagement in all friction points, followed by de-escalation.35 The resumption of the broader bilateral relationship is dependent on peace and tranquility being restored along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China border areas, and efforts to this end.

However, the Chinese position is less understood, and it has evolved over the past four years. This analysis holds particular relevance for explaining the Chinese position. From April to September 2020, the Chinese position was to hold India responsible for the tensions and put the onus of de-escalating tensions on India. It also asked India to delink the situation in eastern Ladakh from the broader bilateral relationship. From September 2020 to September 2022, China signaled a willingness to partially disengage but still disagreed by and large that the border situation should affect overall India-China relations. Between September 2022 and June 2024, China signaled its unwillingness to disengage in the remaining friction points —Depsang and Demchok. It treated them as legacy issues predating the 2020 standoff and preferred to discuss these as part of a regular border management framework. Preferring to assert that the standoff is over, China stated that it would like to resume and deepen bilateral exchanges. Between July and October 2024, China signaled its willingness to work toward “new progress in consultations on border affairs.”36 This has resulted in an agreement on patrolling, which was announced on October 21, 2024 and has led to the completion of disengagement in December 2024.37

Phase 1: Tensions, Crisis Management, and Beginning Negotiations on Disengagement, April 2020–September 2020

This phase was characterized by both sides attempting to manage the crisis, especially in the wake of the Galwan incident, and beginning negotiations to resolve the standoff. Briefly, the Chinese position was to hold India responsible for the Galwan incident and the tensions in eastern Ladakh, thereby putting the onus of reducing tensions on India. It also asked India to place the border tensions in the context of the broader benefits and the “strategic picture” of the India-China relationship and thus to moderate its position. Lastly, it did not agree to India’s demand for complete disengagement, instead advocating de-escalation without disengagement.38

Of the three channels of negotiation, it was the SHMCs that first met in the standoff on June 6, 2020. India noted that the meeting “took place in a cordial and positive atmosphere” and that “both sides agreed to peacefully resolve the situation in the border areas.” It also put forth that both sides agreed to this approach “keeping in view the agreement between the two leaders that peace and tranquility in the India-China border regions is essential for the overall development of bilateral relations.”39 China noted that “both sides agree to implement the important consensus of the two leaders, avoid escalation of differences into disputes, work together to uphold peace and tranquility in the border area, and create favorable (sic) atmosphere for the sound and stable development of bilateral relations.”40 The Chinese statement also sounded a positive note: “Both sides have the willingness and capability to properly resolve the related matters through negotiation and consultation.”

This atmosphere was vitiated after the Galwan incident on the night of June 15, 2020, that left twenty soldiers dead on the Indian side, and at least four on the Chinese side.41 These were the first fatalities on the border in four decades, and both sides held each other responsible.42 India noted that “the Chinese side departed from the consensus to respect the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Galwan valley” and that the “violent face-off happened as a result of an attempt by the Chinese side to unilaterally change the status quo there.”43 Further, the casualties “could have been avoided had the agreement at the higher level been scrupulously followed by the Chinese side.” China likewise held India responsible. MFA spokesperson Zhao Lijian stated that “the Indian troops seriously departed from such consensus, crossed the LAC for illegal activities, and provoked and attacked Chinese personnel, which caused violent physical clashes between the two sides that led to casualties. . . . The right and wrong of this matter is very clear. It happened on the Chinese side of the LAC. The onus is not on China.”44

Both sides attempted to manage the crisis in a series of meetings in the two weeks after the Galwan incident. EAM S. Jaishankar and State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke on the phone on June 17, 2020. Both sides again held the other responsible for the incident, underscored the seriousness of the situation, and put the onus on each other to take corrective action. EAM Jaishankar noted that China’s actions “reflected an intent to change the facts on ground in violation of all our agreements to not change the status quo” and “underlined that this unprecedented development will have a serious impact on the bilateral relationship.”45 He also stated that “the need of the hour was for the Chinese side to reassess its actions and take corrective steps.” Foreign Minister Wang noted that “the Indian forces crossed the Line of Actual Control again, made deliberate provocations and even violently attacked the Chinese soldiers who went for negotiations. This subsequently led to fierce physical clashes and resulted in casualties. The adventurism of the Indian army seriously violated agreements on border issues between the two countries and severely violated basic norms governing international relations. . . . We urge the Indian side to . . . ensure such incidents will not occur again.”46

Foreign ministers Jaishankar and Wang also defined the path forward for negotiations. EAM Jaishankar noted that “both sides would implement the disengagement understanding of 6 June sincerely. Neither side would take any action to escalate matters and instead, ensure peace and tranquility as per bilateral agreements and protocols.”47 The Chinese statement too put forth that “the two sides agreed to fairly address the serious situation caused by the conflict in the Galwan Valley, jointly observe the consensus reached at the commander-level meeting between the two sides, cool down the situation on the ground as soon as possible, and maintain peace and tranquility in the border area in accordance with the agreements already reached between the two countries.”48

On June 20, 2020, MEA spokesperson Anurag Srivastava detailed India’s position on the Galwan incident and the broader tensions in eastern Ladakh.49 On China’s claim that the Galwan Valley was located on the Chinese side of the LAC, he noted that the position was “historically clear,” and “attempts by the Chinese side to now advance exaggerated and untenable claims with regard to Line of Actual Control (LAC) there are not acceptable. They are not in accordance with China’s own position in the past.” He then held China responsible for “hindering India’s normal, traditional patrolling pattern in this area” since early May 2020. He noted that in mid-May, the Chinese side “attempted to transgress the LAC in other areas of the Western Sector of the India-China border areas,” which were “met with an appropriate response.” Thereafter, “the two sides were engaged in discussions through established diplomatic and military channels to address the situation arising out of Chinese activities on the LAC,” and the “Senior Commanders met on 6 June 2020 and agreed on a process for de-escalation and disengagement along the LAC that involved reciprocal actions.” He then reiterated India’s position that the Chinese side “departed from these understandings . . . sought to erect structures just across the LAC . . . [and] when this attempt was foiled, Chinese troops took violent actions on 15 June 2020 that directly resulted in casualties.” He then concluded with India’s expectation that the “Chinese side will sincerely follow the understanding reached between the Foreign Ministers to ensure peace and tranquility in the border areas, which is so essential for the overall development of our bilateral relations.”

A second SHMCL meeting was held on June 22, 2020, which, according to India, focused on the “implementation of the understandings previously reached between the two sides on 06 June 2020.”50 China noted that both sides “on the basis of the first commander-level talks, had an in-depth and candid exchange of views on outstanding issues in border management and control and agreed to take necessary measures to lower the temperature.”51

In the WMCC meeting of June 24, 2020, India recalled the conversation between the foreign ministers and “reaffirmed that both sides should sincerely implement the understanding on disengagement and de-escalation” reached on June 6, 2020, and the “two delegations agreed that implementation of this understanding, in accordance with the bilateral agreements and protocols, would help ensure peace and tranquillity in border areas and the development of broader relationship between the two countries.”52 The Chinese side too referenced the understandings reached by the foreign ministers as well as the SHMCL meetings on June 6 and June 22.53

The SHMCs met for their third round of talks on June 30, 2020. In a nutshell, both sides noted that they were in contact at the diplomatic and military levels to disengage and de-escalate. There were traces of a positive framing to both sides’ remarks, with India noting that “the discussions in the latest meeting of the Senior Commanders reflected the commitment of both sides to reduce the tensions along the LAC.”54 China stated that the two sides “made progress in effective measures by frontline troops to disengage and deescalate the situation. China welcomes that.”55

The Special Representatives on the India-China boundary question had a telephone conversation on July 5, 2020, reviewing the situation in the border areas and detailing the path forward that both sides desired.56 India’s statement noted that both sides took guidance from the leader-level consensus that “maintenance of peace and tranquillity in the India-China border areas was essential for the further development of our bilateral relations and that two sides should not allow differences to become disputes.”57 Thus, both sides agreed that “it was necessary to ensure at the earliest complete disengagement of the troops along the LAC and de-escalation from India-China border areas for full restoration of peace and tranquillity.” Therefore, both sides “should continue their discussions . . . and implement the understandings reached in a timely manner to achieve” these outcomes.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi, China’s Special Representative, noted that “both sides should pay great attention to the current complex situation facing China-India bilateral relations.”58 Both sides “reached positive common understandings,” which were four-fold. First, “peace and tranquility in the border areas matters significantly to the long-term development of bilateral relationship,” but “the boundary question should be placed properly in the bilateral relations, and that an escalation from differences to disputes should be avoided.” Second, “both sides reiterated adherence” to their border agreements and “making joint efforts to ease” the border situation. Third, both sides would “strengthen communication” through the Special Representatives and WMCC mechanisms in order to forestall “more incidents that undermine peace and tranquility in the border areas.” Fourth, “both sides welcomed the progress” in negotiations, agreed to stay in communication, and “stressed the importance to promptly act on the consensus reached” at the SHMCL and “complete disengagement . . . as soon as possible.”

The disengagement process continued in July, and both sides recognized this. The WMCC met on July 10, 2020, and India noted that both sides reviewed the border situation “including the progress made in ongoing disengagement process along the LAC in the Western Sector.”59 China too noted that “both sides fully recognized . . . the positive progress in relaxation of the current regional situation.”60 The SHMCs met on July 14 as well. India noted that they “reviewed the progress on implementation of the first phase of disengagement,” and China also put forth that “the two sides achieved progress in further disengagement between border troops as well as easing the situation at the western sector of the China-India boundary.”61 It was reported that disengagement was completed at PP-14 in the Galwan Valley toward the end of July.62

However, differences emerged on the extent of disengagement and the remaining steps to peace and tranquility. The MFA noted, “As border troops have disengaged in most localities, the situation on the ground is deescalating and the temperature is coming down.”63 Responding to these assertions, the MEA stated, “There has been some progress made towards this objective but the disengagement process has as yet not been completed.”64

The differences between both sides became apparent in August. The SHMCs met on August 2, 2020, yet there was no statement from either side. Reports noted that talks took place for nearly eleven hours with “no meeting ground,” and the two sides did not agree to each other’s proposals.65 Compared to India’s stand that peace and tranquility in the border areas was necessary for the broader bilateral relationship, the MFA noted on August 4, 2020, that the border issue must always be placed “in an appropriate position in bilateral relations.”66 It was reported on August 14 that the disengagement process appeared to have stalled due to reluctance on the Chinese side.67 In the WMCC meeting on August 20, India noted that both sides “will continue to work towards complete disengagement” and that they were in agreement that “restoration of peace and tranquillity in the border areas would be essential for the overall development of bilateral relations.”68 China’s statement did not mention these points.69 By contrast, on August 27, China’s MND asked India to approach the border situation “bearing in mind the big picture of bilateral ties and putting the border issue in an appropriate position in this big picture.”70

It was in the context of these differences, lack of disengagement, and signs that China was again attempting to change the status quo that the Indian Army launched Operation Snow Leopard at the end of August. This was an attempt to block the People’s Liberation Army’s maneuvers, gain tactical advantage, and use it as leverage in the negotiations on the standoff.71

Operation Snow Leopard and Meetings at the Politico-Strategic Level

Operation Snow Leopard, coordinated with messaging at the politico-strategic level, played a key role in inducing progress in the negotiations. Approximately twenty days after it commenced, a shift in the Chinese position and attitude toward negotiations became perceptible. The following section provides further details of the developments in these twenty days.

The first official information about the operation came on August 31, 2020, through a Press Information Bureau release by the MoD.72 It stated that on the night of August 29, the PLA “violated the previous consensus” and “carried out provocative military movements to change the status quo.” As a consequence, “Indian troops pre-empted this PLA activity on the Southern Bank of Pangong Tso,” and took actions to “thwart Chinese intentions to unilaterally change facts on ground.” The MEA reiterated this on September 1 and shared that even as ground commanders were in discussions to de-escalate tensions, “the Chinese troops again engaged in provocative action” on August 31.73 Reflecting on the Chinese side’s behavior along the LAC since April, the MEA noted that it had been “in clear violation of the bilateral agreements and protocols concluded between the two countries to ensure peace and tranquility on the border.” These actions were also in “complete disregard to the understandings reached” at the politico-strategic level between the foreign ministers and special representatives.

The MFA took the position on September 1, 2020, that “Indian troops again illegally crossed the LAC at the southern bank of the Pangong Tso Lake and near the Reqin Mountain,” and that these “flagrant provocations again led to tensions.”74 It noted that India had “severely undermined China’s territorial sovereignty, breached bilateral agreements and important consensus, and damaged peace and tranquility in the border areas.” It put the onus on India to de-escalate tensions, asking India to “take concrete actions to ensure the peace and tranquility of the border areas and the sound development of China-India relations.”

On September 3, 2020, the MEA noted that “now the way ahead is negotiations, both through the diplomatic and military channels,” and “we therefore strongly urge the Chinese side to sincerely engage the Indian side with the objective of expeditiously restoring the peace and tranquility in the border areas through complete disengagement and de-escalation in accordance with the bilateral agreements and protocols.”75

In the context of these developments, India and China’s defense ministers met on September 4, 2020, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s meeting of defense ministers.76 Since the beginning of the standoff, this was the first in-person meeting at the politico-strategic level between India and China and helped break the ice at the political level.77 The meeting took place at the request of the Chinese side.78 The Indian side had communicated to Russia that if a meeting was requested by the Chinese, India would not be averse to it.79 The Indian objectives heading into this meeting were to establish in-person political contact with the Chinese, as well as to understand China’s motivations for its actions since April–May 2020.80 According to an Indian stakeholder, the Chinese objectives were to stabilize the situation in the aftermath of Operation Snow Leopard, remove India’s incentives for further escalation, and also to gauge whether India had other options to this end.81 In this meeting, both countries differed on the next steps to resolve tensions and where to place the standoff in bilateral ties. According to the Indian statement, Chinese state councilor and defense minister, Wei Fenghe, said that both sides should “focus on the overall situation of India-China relations and maintain peace and tranquillity in the India-China border areas.” To this, Indian defense minister, Rajnath Singh, responded that both sides should take guidance from the leaders’ consensus that “maintenance of peace and tranquility in the India-China border areas was essential for the further development of our bilateral relations.” Defense Minister Wei conveyed that the “Chinese side too desired to resolve the issues peacefully,” to which Defence Minister Singh responded that “it was important therefore that Chinese side should work with the Indian side for complete disengagement at the earliest from all friction areas including Pangong Lake as well as de-escalation in border areas.” China’s remarks noted that Defense Minister Wei suggested that both sides should “set eyes on the big picture of China-India relations and regional peace and stability.”82

Six days later, on September 10, 2020, India’s and China’s foreign ministers met in Moscow on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s meeting of foreign ministers. This was arguably the most important interaction yet in the standoff. The meeting was prepared by the capitals, in Delhi and Beijing.83 This meant that positions and possible outcomes were discussed before the meeting by both sides—between the MEA and Chinese representatives in New Delhi, and the MFA and Indian representatives in Beijing. The foreign ministers held two meetings in Moscow—the first with a larger delegation and a second with closer aides.84 While both sides had their differences, they felt there was enough consensus and semblance of a framework to address the standoff, which was worth codifying.85 Thus, the meetings resulted in a joint press statement as well as separate statements from both sides. The joint statement was the first such arising out of any meeting on the standoff held so far through the three channels of negotiation.86 This signaled that in this period of crisis, both sides agreed on a common path forward for negotiations and for a path out of the crisis. The statement noted that both sides had a “frank and constructive discussion on the developments in the India-China border areas as well as on India-China relations.” The five-point statement is placed below.

- The two Ministers agreed that both sides should take guidance from the series of consensus of the leaders on developing India-China relations, including not allowing differences to become disputes.

- The two Foreign Ministers agreed that the current situation in the border areas is not in the interest of either side. They agreed therefore that the border troops of both sides should continue their dialogue, quickly disengage, maintain proper distance and ease tensions.

- The two Ministers agreed that both sides shall abide by all the existing agreements and protocol on China-India boundary affairs, maintain peace and tranquillity in the border areas and avoid any action that could escalate matters.

- The two sides also agreed to continue to have dialogue and communication through the Special Representative mechanism on the India-China boundary question. They also agreed in this context that the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China border affairs (WMCC), should also continue its meetings.

- The Ministers agreed that as the situation eases, the two sides should expedite work to conclude new Confidence Building Measures to maintain and enhance peace and tranquillity in the border areas.

While there was consensus, there were differences as well, thus both sides released separate statements from this meeting, laying out their respective positions. EAM Jaishankar noted that it was “clear that the maintenance of peace and tranquility on the border areas was essential to the forward development of ties” and that “recent incidents in eastern Ladakh “inevitably impacted the development of the bilateral relationship.”87 It was also highlighted that “the massing of Chinese troops with equipment along the LAC . . . was not in accordance with the 1993 and 1996 Agreements and created flash points.” Further, the “provocative behavior of Chinese frontline troops . . . showed disregard for bilateral agreements and protocols.” The Indian side conveyed its expectation of “full adherence to all agreements on management of border areas.” Finally, “the immediate task” was to ensure a “comprehensive disengagement of troops in all the friction areas.”

On the other hand, Foreign Minister Wang noted that it was important to put differences “in a proper context vis-a-vis bilateral relations.”88 In comparison to the Indian position that the border situation would determine the development of the bilateral relationship, he noted that in “difficult” situations, “it is all the more important to ensure the stability of the overall relationship.” Difficulties could be overcome as long as both sides “keep moving the relationship in the right direction.” He too noted that “frontier troops must quickly disengage so that the situation may de-escalate.”

On September 15, 2020, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh addressed the Indian Lok Sabha (House of the People) about the situation in eastern Ladakh, and it stands as the most detailed articulation of the Indian position yet.89 He briefed the house about India’s boundary dispute with China, the present standoff, and India’s approach to it. While noting that both India and China had formally agreed that the boundary question is a “complex issue which requires patience,” he stated that in the interim, the two sides have also agreed that “maintenance of peace and tranquility in the border areas is an essential basis for the further development of bilateral relations.” He further added that “the two sides have agreed to maintain peace and tranquility along the LAC without prejudice to their respective positions on the alignment of the LAC as well as on the boundary question,” and it is “on this basis, that our overall relations also saw considerable progress since 1988.” He also said, “India’s position is that while bilateral relations can continue to develop in parallel with discussions on resolving the boundary question, any serious disturbance in peace and tranquility along the LAC in the border areas is bound to have implications for the positive direction of our ties.”

He held China responsible for the tensions in eastern Ladakh, the Galwan incident, and its “provocative military manoeuvres on the night of 29th and 30th August in an attempt to change the status quo in the South Bank area of Pangong Lake.” He noted that Chinese actions “reflect a disregard” of the bilateral agreements between the two sides and that “this year, the violent conduct of Chinese forces has been in complete violation of all mutually agreed norms.” He also stated that the situation “this year is very different both in terms of scale of troops involved and the number of friction points.”

He detailed the three key principles that determine India’s approach to the border situation. First, “both sides should strictly respect and observe the LAC.” Second, “neither side should attempt to alter the status quo unilaterally.” Third, “all agreements and understandings between the two sides must be fully abided by in their entirety.”

Phase 1 of the standoff came to an end in September 2020, with a shift in the Chinese position becoming visible in the subsequent round of SHMCL talks on September 20. Indian stakeholders have stated in public and private that Operation Snow Leopard “surprised” the Chinese and “brought them back to the negotiating table.”90 The evidence supports this assertion to a reasonable extent. On the question of whether it surprised the PLA, Operation Snow Leopard was intended as a surprise operation, and the location and scale of the deployment were without precedent as tanks had never been placed on Rezang La and Rechin La previously.91 Regarding the question of whether it induced concern, the MFA stated after the operation that India had “severely undermined China’s territorial sovereignty, breached bilateral agreements and important consensus, and damaged peace and tranquility in the border areas.”92 At the defense ministers’ meeting on September 4, 2020, Wei Fenghe told Rajnath Singh that both sides should “not undertake any provocative actions that might escalate the situation.”93

The argument that the PLA found Operation Snow Leopard threatening is also supported by the PLA’s response at a tactical level. Indian stakeholders have mentioned that the Indian Army took up positions that overlooked the PLA’s Moldo garrison on the south bank of Pangong Tso as well as access routes to it and, if needed, could threaten and interdict these.94 In the years since, the PLA has built a bridge across Pangong Tso, which serves as another access point to the Moldo garrison and to the north bank of Pangong Tso.95 An Indian stakeholder noted that this bridge was to circumvent the threat from another possible occupation of the heights on the north and south banks of Pangong Tso by India in the future, as it had done in Operation Snow Leopard.96

On the question of whether the operation brought China to the negotiating table, the Indian statement from the defense ministers’ meeting on September 4, 2020, notes that the meeting was at the request of the Chinese side. Stakeholders at the operational and strategic levels have also asserted that the Chinese were concerned and more willing to talk after this operation.97 The first sign of consensus in the standoff was the joint press statement from the meeting of the foreign ministers, which came about ten days after the operation. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s statement announcing disengagement to the Lok Sabha in February 2021 also supports the conclusion that Operation Snow Leopard helped move forward the negotiations. He noted that because of it, India “maintained the edge.”98

Phase 2: Disengagement in Four Friction Points, September 2020–September 2022

This phase was characterized by India and China negotiating and disengaging in four locations—PP-15, PP-17, and PP-17A in the Gogra-Hot Springs area, and on the northern and southern banks of Pangong Tso. This was enabled by a tactical shift in China’s position. At times, China agreed on the need for disengagement and de-escalation, the relevance of the same for peace and tranquility in the border areas, and the necessity of peace and tranquility for the development of broader bilateral relations. At other times, China disagreed on these points. It also took the position that continuing talks on the boundary question would help realize peace and tranquility in the border areas. Phase 2 tracks these positions and shifts and attempts to explain some of them.

Following the foreign ministers’ meeting on September 10, 2020, the change in the Chinese position—therefore consensus between India and China—was noticeable in the meetings thereafter. The sixth round of SHMCL talks were held on September 21, 2020. Further indicative of consensus was the fact that the SHMCL talks yielded a joint press release, which was also highlighted by the MEA.99 The release was also framed positively, with both sides having “candid and in-depth” exchanges and agreeing to “earnestly implement” the leader-level consensus. They also jointly agreed to “stop sending more troops to the frontline, refrain from unilaterally changing the situation on the ground, and avoid taking any actions that may complicate the situation.” The WMCC met on September 30, 2020, and, according to India, both sides “attached importance to the meetings between the two Defence Ministers and the two Foreign Ministers” and “positively evaluated the outcome of the 6th Senior Commanders meeting on 21 September.”100 China too noted that both sides “agreed to earnestly implement the five-point consensuses reached by the foreign ministers” and “affirmed the outcomes of the 6th round of Military Commander–level Talks.”101

The aforementioned shift and resultant consensus became more evident in the meetings between October and December 2020. Where the sixth round of SHMCL talks had both sides exchanging views on “stabilizing the situation along the LAC,” the seventh round held on October 12, 2020 was about a “sincere, in-depth and constructive exchange of views on disengagement along the Line of Actual Control in the Western Sector of India-China border areas.”102 Again, a joint statement with “positive, constructive” framing that explicitly mentioned that both sides agreed to “arrive at a mutually acceptable solution for disengagement as early as possible” was released. The MEA again highlighted the joint statement and noted that both sides had a better understanding of each other’s positions.103 The eighth round of SHMCL talks held on November 6, 2020, also yielded a joint statement reiterating a “candid, in-depth and constructive exchange of views on disengagement along the Line of Actual Control in the Western Sector of India-China border areas.”104 The twentieth meeting of the WMCC took place on December 18, 2020. Both sides noted that they would continue to work toward disengagement.105 India stated that both sides noted that the previous two rounds of SHMCL talks had “contributed to ensuring stability on the ground,” and, according to China, “both sides spoke highly of the outcomes of the 8th round of Senior Commanders Meeting.” It can be argued that there was an improved climate for talks by the turn of the year.

The ninth round of SHMCL talks held on January 24, 2021, yielded a significantly positive joint statement. Both sides agreed that this round was “positive, practical and constructive, which further enhanced mutual trust and understanding.”106 They agreed to “push for an early disengagement” and “maintain the good momentum of dialogue and negotiation.”

Four days later, EAM Jaishankar addressed the 13th All India Conference of China Studies, where he commented on India’s relationship with China and reaffirmed India’s position on the standoff.107 “The advancement of ties in this period [the last three decades] was clearly predicated on ensuring that peace and tranquillity was not disturbed and that the Line of Actual Control was both observed and respected by both sides.” The border remained “fundamentally peaceful” prior to 2020, and the events in eastern Ladakh including the loss of life “profoundly disturbed the relationship” and put it under “exceptional stress.” He added, “Any expectation . . . that life can carry on undisturbed despite the situation at the border . . . [is] simply not realistic.” He also laid out eight broad propositions, of which three are directly relevant for India’s position on the standoff. They are placed below.

First and foremost, agreements already reached must be adhered to in their entirety, both in letter and spirit. Second, where the handling of the border areas are concerned, the LAC must be strictly observed and respected; any attempt to unilaterally change the status quo is completely unacceptable. Third, peace and tranquillity in the border areas is the basis for development of relations in other domains. If they are disturbed, so inevitably will the rest of the relationship. This is quite apart from the issue of progress in the boundary negotiations.

Two weeks later, in February 2021, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh announced to the Rajya Sabha (House of States) that India and China had reached an agreement on disengagement at Pangong Tso. He reiterated India’s position and stated that the disengagement would “substantially restore the situation to that existing prior to commencement of the standoff last year.”108 He also noted there were “still some outstanding issues” and that both sides had agreed to “achieve complete disengagement at the earliest.” He also mentioned that “India has consistently maintained that while bilateral relations can develop in parallel with discussions on resolving the boundary question, any serious disturbance in peace and tranquility along the LAC in the border areas is bound to have adverse implications for the direction of our bilateral ties.”

With disengagement completed on the north and south banks of Pangong Tso, both sides turned their attention to the remaining friction points and the way forward for negotiations. Eleven days after Rajnath Singh’s announcement, the tenth round of SHMCL talks were held on February 21, 2021. In a joint statement, both sides “positively appraised the smooth completion of disengagement of frontline troops in the Pangong Lake area.”109 They noted that it was a “significant step forward that provided a good basis for resolution of other remaining issues along the LAC in Western Sector.” Four days later, on February 25, 2021, this was followed by a phone call between foreign ministers Jaishankar and Wang. EAM Jaishankar reiterated that disturbance of peace and tranquility “including by violence” would “inevitably” have a damaging impact on the relationship.110 Recognizing the sustained communication between both sides since September 2020 and the resultant progress, he also restated India’s goal: “It was necessary to disengage at all friction points in order to contemplate de-escalation of forces in this sector. That alone will lead to the restoration of peace and tranquility and provide conditions for progress of our bilateral relationship.”

In a significant statement, Foreign Minister Wang flagged, however, that there had been “some wavering and backpedaling in India’s China policy” and that “heightening differences” would not help resolve problems.111 He noted that the situation on the ground had been “noticeably eased” following the disengagement at Pangong Tso and that both sides should “cherish the hard-won relaxation.” He took the position that both sides needed to “advance the boundary talks to build up mutual trust and realize peace and tranquility in the border areas.” Further, while the “boundary disputes” were an “objective fact, which should be taken seriously,” they were not the whole of India-China relations and should be put at a “proper place” in bilateral ties. These remarks indicated some difference with the Indian side’s view on the way forward.

The statements from both sides in the meetings held thereafter—between March and June 2021—reveal the differences between their viewpoints. The WMCC met for its twenty-first meeting on March 12, 2021. India reiterated the position that complete disengagement from all friction points would allow both sides to look at de-escalation and work toward restoration of peace and tranquility in the border areas.112 China’s statement mentioned “resolution of other issues” but not disengagement explicitly. It noted that both sides agreed to hold the next round of SHMCL meetings to “further de-escalate the situation on the ground” and to jointly maintain the “hard-earned peace and tranquility in the border areas.” On April 2, 2021, the MEA highlighted EAM Jaishankar’s comment to Foreign Minister Wang that prolonging the situation was in neither side’s interest, therefore “we hope that the Chinese side will work with us” to ensure that the disengagement in the remaining areas was completed “at the earliest.”113 On April 10, 2021, the eleventh round of SHMCL talks was held. After joint statements from the previous five rounds, this meeting did not result in one, indicating differences. India reiterated its position.114 China again noted its hope that the Indian side could "cherish the positive trend of de-escalation in the region . . . and work together with China to safeguard peace and tranquility in the area.”115 The MND too, on April 29, 2021, noted its “hope that the Indian side will cherish the hard-won outcome.”116

A call was arranged between the foreign ministers on April 30, 2021 “at the request of the Chinese side to convey their sympathy and solidarity with India,” with the context being the devastating second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic sweeping across India.117 The two sides also discussed the standoff, with EAM Jaishankar highlighting his concerns and pushing back on the Chinese position. First, the Indian statement said that the two ministers “discussed the outstanding issues related to disengagement from all friction points along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Eastern Ladakh,” thereby signaling that work remained to be done.118 EAM Jaishankar further conveyed that while the process of disengagement had commenced earlier that year, “it remained unfinished” and that it was “necessary that this process be completed at the earliest.” Lastly, he emphasized that “full restoration” of peace and tranquility in the border areas would enable progress in the bilateral relationship. Regarding the standoff, the Chinese statement only mentioned that both sides “also exchanged ideas on bilateral relations.”119

The differences persisted in the twenty-second meeting of the WMCC held on June 25, 2021. India reiterated its position and noted that the two sides agreed to hold the twelfth round of SHMCL talks at an “early date to achieve the objective of complete disengagement from all the friction points along the LAC.”120 China did not mention disengagement in its statement.121 As it had in previous months, it continued to take the position that both sides would “continuously make efforts to further de-escalate the border situation” and work together to “maintain peace and tranquility in the border areas.”

Amidst these differences, the foreign ministers met in Dushanbe on July 14, 2021, on the sidelines of the SCO meeting of foreign ministers. This was their first in-person meeting since the one in Moscow in September 2020. Apart from restating the Indian position, EAM Jaishankar “emphasized the need to follow through on the agreement” reached in September 2020 and “complete the disengagement.”122 He conveyed his expectation that the Chinese side would work with India toward this objective, but he noted “that the situation in remaining areas is still unresolved.” He recalled both sides’ agreement that prolonging the existing situation was not in either side’s interest, and it was “visibly impacting the relationship in a negative manner.” By contrast, Foreign Minister Wang Yi asserted that after the disengagement in the Galwan Valley and Pangong Tso, the “overall situation in the border area was de-escalated.”123 He reiterated the Chinese position of placing the border issue in an “appropriate position” in bilateral relations and stated that “we must take a long-term perspective and gradually move from emergency response toward regular management and control,” to avoid India-China relations being subject to “unnecessary interruptions” by border-related issues. Despite the differences, both sides agreed to continue negotiations through the existing channels to work toward a mutually acceptable outcome.

Consensus and subsequent disengagement came at the end of July 2021. The SHMCs met on July 31 for their twelfth round of interactions. This meeting resulted in a joint statement, indicating consensus for the first time since February 2021.124 Containing positive framing, it noted that this meeting was held following the one of the foreign ministers on July 14 and that of the WMCC on June 25. It was separately reported that the lack of consensus was bridged by the WMCC and then the foreign ministers’ meetings.125 In the SHMCL meeting, the two sides discussed disengagement and agreed to resolve remaining issues in an “expeditious manner.” Seven days later, the MoD announced that as an outcome of the meeting, both sides had disengaged at PP-17A in the Gogra area.126 It noted that both sides “expressed commitment to take the talks forward and resolve the remaining issues along the LAC in the Western Sector.”

The foreign ministers met in Dushanbe again on September 16, 2021, on the sidelines of the SCO meeting of the heads of states. EAM Jaishankar took cognizance of the disengagement in the Gogra area, “however there were still some outstanding issues that needed to be resolved.”127 China’s statement from the meeting noted that the meeting took place at the request of the Indian side.128 Foreign Minister Wang Yi asserted that the border situation had “gradually de-escalated” and hoped India would help shift the border situation “from urgent dispute settlement to regular management and control.” These statements were indicative of differences in both countries’ positions.

The differences between India and China came to the fore in the thirteenth round of SHMCL talks held on October 10, 2021. The meeting did not yield a joint statement; rather, it resulted in separate statements with forthcoming language where both sides held each other responsible for the continuing standoff. The Indian side highlighted that the standoff had been caused by “unilateral attempts of Chinese side to alter the status quo and in violation of the bilateral agreements.”129 Thus, it was necessary that China take “appropriate steps in the remaining areas so as to restore peace and tranquility along the LAC in the Western Sector.” Accordingly, the Indian side “therefore made constructive suggestions for resolving the remaining areas but the Chinese side was not agreeable and also could not provide any forward-looking proposals.” Holding China responsible, “the meeting thus did not result in resolution of the remaining areas.” Lastly, given that China had indicated its preference that India approach the border situation from a broader bilateral outlook, India used this framing to convey the opposite. The Indian statement noted its “expectation that the Chinese side will take into account the overall perspective of bilateral relations and will work towards early resolution of the remaining issues.” The spokesperson for the PLA’s Western Theater Command commented on the talks, terming India’s demands “unreasonable and unrealistic,” and suggested that India “cherish the hard-won situation in China-India border areas.”130 The MFA further termed India’s remarks “groundless.”131

Differences continued to appear in the meetings thereafter. The WMCC met again on November 18, 2021, with India standing by its demands of complete disengagement, de-escalation, and restoration of peace and tranquility in the border areas.132 China’s statement noted that both sides would “work for an earlier shift from emergency response to routine control,” and that they agreed to “consolidate the current outcomes of disengagement.”133 Both sides agreed to work toward holding the fourteenth round of SHMCL talks. India’s ambassador in Beijing at the time, Vikram Misri, held a virtual farewell call with Foreign Minister Wang Yi on December 6, 2021. While Misri “underlined his continued hope that complete resolution” of the border issues “as per the understanding between the two Foreign Ministers would be achieved soon,” Foreign Minister Wang posited that both sides needed to build mutual trust as the way forward.134

Given the gaps between the two sides’ positions, it was interesting that joint statements emerged from the fourteenth and fifteenth rounds of SHMCL talks held on January 12, 2022, and March 11, 2022, respectively. The statement from the fourteenth round of talks did not mention the goal of disengagement explicitly, which India had repeatedly stated was key.135 It instead less explicitly mentioned that both sides agreed to work for the “resolution of the remaining issues.” The statement also espoused that resolution of the remaining issues would “help in restoration of peace and tranquility along the LAC in the Western Sector and enable progress in bilateral relations.” Given that China had repeatedly been asking India to put the border situation in an appropriate place in bilateral relations, it was interesting that China agreed to this statement. Both sides also agreed to hold the fifteenth round of SHMCL talks “at the earliest” to work out a “mutually acceptable resolution.” The MND commented on the fourteenth round of talks two weeks later, noting that the meeting was held in a “candid and friendly mood” and that it believed that this round of talks was “positive and constructive.”136 In the fifteenth round held on March 11, 2022, both sides “carried forward their discussions from the previous round” and “reaffirmed that . . . resolution would help restore peace and tranquility along the LAC in the Western Sector and facilitate progress in bilateral relations.”137

In hindsight, it is possible that this recent consensus was due to both sides attempting to create a more favorable atmosphere for a visit at the politico-strategic level. Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrived in New Delhi on March 24, 2022, for a working visit that was not previously publicly announced.138 Since the beginning of the standoff in 2020, this was the first bilateral visit to either country by representatives of either side at the politico-strategic level—as opposed to meetings in other countries on the sidelines of multilateral summits.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi met EAM Jaishankar and as well as NSA Ajit Doval. EAM Jaishankar briefed the press on his meeting.139 He noted that it had been a “challenge” to implement the understanding between the two sides on disengagement and de-escalation. Disengagement needed to be “taken forward since the completion of disengagement is necessary for discussions on de-escalation to take place.” He described the situation as a “work in progress, obviously at a slower pace than desirable” and noted that his discussions with Foreign Minister Wang were “aimed at expediting the process.” He responded to the Chinese side’s calls for normalcy and the broader significance of India-China ties, emphasizing that he “was equally forthcoming that India wants a stable and predictable relationship. But restoration of normalcy will obviously require a restoration of peace and tranquillity.” He also noted that “if we are both committed to improving our ties, then this commitment must find full expression in ongoing disengagement talks.”

Foreign Minister Wang reiterated that the boundary issue be put in a proper place in bilateral ties, but he also acknowledged EAM Jaishankar’s position that both sides should “disengage each other in the remaining parts as soon as possible.”140 The statement also noted agreement between the two sides that “it is in the common interests of both countries to restore peace and tranquility in the border areas, and the two countries should achieve regular management and control of the areas on the basis of disengagement.”

China’s statement from the meeting with NSA Doval did not mention disengagement or peace and tranquility. Instead, Foreign Minister Wang suggested that as special representatives on the boundary question, both sides should “strive to switch from emergency response to normalized management and control of the boundary issue as soon as possible, make unswerving efforts toward proper management and control of the border issue, and seek a fair and just solution.”141 An official statement by the Indian side could not be sourced. Asian News International reported that NSA Doval conveyed to Foreign Minister Wang that there had to be “early and complete disengagement” in border areas for ties to move forward, and that peace and tranquility would help build mutual trust and create an environment conducive to progress in bilateral ties.142 It was also reported that the Chinese side invited NSA Doval to visit China to take forward the mandate of the special representatives. NSA Doval was reported to have said that he could visit China after immediate issues were resolved successfully.

In this situation of consensus on some points but disagreement on others, the WMCC met two months later on May 31, 2022. Both sides referenced the consensus between the two foreign ministers and agreed to hold the sixteenth SHMCL meeting at an early date. India reiterated its demand for complete disengagement, whereas China’s statement mentioned “dealing with the outstanding issues about the western section of the boundary under the principle of mutual and equal security.”143 India’s new ambassador in Beijing, Pradeep Kumar Rawat, called on Foreign Minister Wang Yi on June 22, 2022. The former emphasized “the criticality of maintenance of peace and tranquility in the border areas for realizing the full potential” of the leader-level consensus between the two sides on the importance of India-China relations.144 Foreign Minister Wang restated that the boundary issue should be viewed appropriately in the context of bilateral ties.145 He also mentioned that both sides should work “in the same direction to maintain the warming momentum in China-India relations and bring them back to the track of stable and sound development at an early date.” India’s statement mentioned that both sides agreed to make “full use of the opportunities provided by multilateral meetings to continue their exchange of views including between the two Foreign Ministers.”146

Approximately two weeks later, on July 7, 2022, foreign ministers Jaishankar and Wang met on the sidelines of the G20 foreign ministers’ meeting in Bali. EAM Jaishankar called for an “early resolution of all the outstanding issues along the LAC in Eastern Ladakh,” recalled the disengagement achieved so far, and “reiterated the need to sustain the momentum to complete disengagement from all the remaining areas to restore peace and tranquility in the border areas.”147 Foreign Minister Wang again did not mention disengagement or peace and tranquility.148 He said that since March, China and India had maintained communication, “effectively managed differences, and bilateral relations have generally shown a recovery momentum.” He also suggested that both countries should “push for the early return of bilateral relations to the right track.” India’s statement also mentioned that both ministers looked forward to the next round of SHMCL talks at an early date, though China’s statement did not mention this.149

Following this meeting, the sixteenth round of SHMCL talks was held ten days later on July 17, 2022. The resultant joint statement mentioned that “building on the progress made at the last meeting on 11 March 2022,” both sides continued discussions in a “constructive and forward looking manner” and had a “frank and in-depth exchange of views.”150 They reaffirmed that resolution of remaining issues would help in restoration of peace and tranquility along the LAC in the Western sector and enable progress in bilateral relations. They agreed to stay in touch through military and diplomatic channels to reach a mutually acceptable resolution of the remaining issues “at the earliest.”

On July 25, 2022, Xi Jinping sent a congratulatory message to Indian president Droupadi Murmu on her inauguration.151 As per the author’s record, this was the first public communication from Xi Jinping himself containing a message about the standoff and bilateral ties since the latter commenced in April–May 2020. He noted that he was “ready to work with President Murmu to enhance political mutual trust . . . properly handle differences and push India-China relations forward on the right track.” Approximately six weeks later, on September 8, 2022, both sides announced disengagement in the Gogra-Hot Springs area (PP-15) in a short joint statement.152 This was noted to be “conducive to the peace and tranquility in the border areas.” The MEA noted that both sides mutually agreed to take the talks forward, resolve the remaining issues along the LAC, and restore peace and tranquility in India-China border areas.153

With this disengagement, Phase 2 of the standoff came to an end. The study of this phase yields the following takeaways.

- After the disengagements in February and August 2021, the Chinese side would adopt a hardened position and push back on Indian demands for disengagement. This would be the case even if they were to eventually agree to disengagement thereafter. Stakeholders at the strategic level of command and with experience of negotiating with the Chinese explained that this was a negotiation tactic, meant to tire the resolve of the other side.154

- In response to India’s suggested path of disengagement, de-escalation, restoration of peace and tranquility in the border areas, and bilateral exchanges to be resumed in consonance with these, China attempted to employ three tactics at various times. First, it posited that peace and tranquility were already present, therefore bilateral exchanges should resume. Second, it attempted to delink border issues from broader relations, so that bilateral exchanges could resume. Third, it suggested that moving forward, boundary talks and building up mutual trust would have positive effects on peace and tranquility in the border areas.

- In the months leading up to Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit in March 2022, both sides attempted to arrive at a tactical consensus to achieve an atmosphere conducive to the visit. While India had consistently mentioned complete disengagement in the negotiations on the standoff, it used less explicit language in the leadup to Foreign Minister Wang’s visit. Between November 18, 2021, and March 25, 2022, through two rounds of SHMCL talks, six weekly MEA press briefings, and the farewell call between Vikram Misri and Wang, the Indian side did not mention disengagement in its official statements and instead mentioned “resolution.” During Wang’s visit and thereafter, India resumed advocating for complete disengagement from all friction points. China too sought consensus and agreed in joint statements leading up to Wang’s visit that disengagement was necessary for restoration of peace and tranquility in the border areas, which was further necessary for the development of bilateral ties. It would disagree with this assertion at other points in the standoff.

Phase 3: Differences and Disengagement in Depsang and Demchok, September 2022–December 2024

This phase from September 2022 to June 2024 witnessed a slowdown in the negotiations to resolve the standoff. This is due to both sides having been increasingly at odds with each other’s positions regarding disengagement in the remaining friction points of Depsang and Demchok. In a nutshell, China took the position that Depsang and Demchok were legacy issues that predated the present standoff and should therefore be discussed as part of a normalized and routine border management framework.155 Preferring to assert that the standoff was over given disengagement in the rest of the friction points, it pushed for the resumption of broader bilateral engagements. India took the position that Depsang and Demchok should be discussed as part of negotiations on the present standoff.156 The Indian side acknowledged that Depsang and Demchok have had issues prior to 2020.157 However, the situation on the ground also changed qualitatively in April–May 2020, when Chinese troops took up positions that restricted the ability of Indian troops to patrol up to certain patrol points in both Depsang and Demchok.158 In Depsang, the PLA blocked Indian patrols at a bottleneck known as Y-Junction. This prevented Indian troops from patrolling up to PPs 10, 11, 11A, 12, and 13, which they last accessed in January/February 2020.159 In Demchok, Chinese troops blocked Indian patrols at the Charding Ninglung Nallah junction, where China pitched tents, preventing Indian troops from patrolling up to their limits.160 Previously, the Indian army used to patrol up to Charding La (a mountain pass) once or twice a year, even though the Chinese unsuccessfully attempted to block the patrols.161 China had set up tents on the Indian side of Charding La a “couple of years” before 2020, and the presence expanded in April 2020.162

In India’s view, after disengagement from these two points, both sides should de-escalate, restore peace and tranquility in the border areas, and move forward the bilateral relationship. Both sides signaled the differences in their positions through all the three channels of negotiation—the SHMCL talks, WMCC meetings, and meetings at the politico-strategic level. Since July 2024, however, both sides have made a renewed attempt to find meeting ground and engaged in sustained negotiations at all three levels. This has resulted in an agreement on patrolling in Depsang and Demchok that has led to disengagement.