As Saudi Arabia faces the two-year anniversary of the Arab Spring, its oil-rich Eastern Province is caught between bitter disappointments and glimmers of hope. It was here where activists from the country’s Shia minority, inspired by Tunis and Tahrir Square, staged protests demanding the release of political prisoners, political reforms, and an end to discrimination. Now, in the wake of a regime crackdown that has left 15 dead (some sources report as many as 21), and countless others imprisoned, dissent has not abated but rather is marked by intense generational debates about goals, strategy and the prospects for real change.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Awamiya, an impoverished Shia town ringed by date groves in the Eastern Province. To enter, one relies on local guides to circumvent the official checkpoints that dot the main roads. Once inside, the town is a warren of car repair shops, crumbling buildings, and restless young men. It is a city under siege where gunshots routinely punctuate the night.

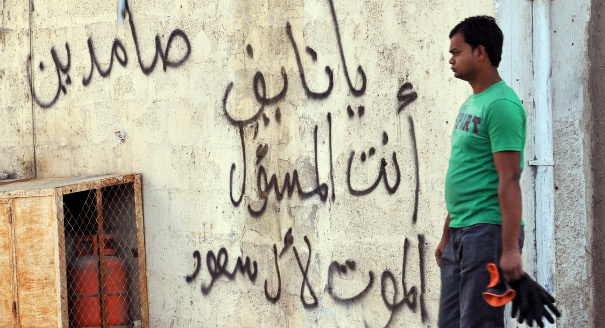

After passing Dignity Circle—self-consciously modeled after Bahrain’s Pearl Roundabout—a massive police fort appears, closeted by turrets and armored vehicles and, finally, a ramshackle structure strung with black flags and loudspeakers. This is the local mosque of Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, the populist Shia cleric whose July 2011 injury and imprisonment by security forces has become a touchstone for the near-nightly protests there and elsewhere in the Eastern Province. The regime says al-Nimr preaches violence and secession at the behest of Iran, putting his youthful followers on par with the al-Qaeda threat the Kingdom confronted several years back. But in his sermons and statements—often plastered on the walls of Awamiya—he rejects violence and calls for sweeping reforms: an end to sectarian discrimination, a release of political prisoners, greater representation, and economic development of a town that, ironically, borders a major oil pipeline. Above all, al-Nimr appeals for dignity; “Nimr speaks to what we are feeling in hearts,” asserted one young activist, still limping from a bullet wound.

“Awamiya is just the opening of the volcano,” one local cleric said. “And you don’t judge the size of the volcano from its opening.” Among the youth in neighboring Qatif, activists are arguing for newer, bolder approaches that differ markedly from the cautious dialogue espoused by the older generation of intellectuals and activists—the so-called “Islahiyyin.” For some, especially in Awamiya, these once-venerated figures are seen as being out of touch and too close to the government—a disenchantment that reached its apogee in the summer of last year, when 40 Shia clerics issued a statement forbidding violent tactics. These missives were intended to counter the infiltration of armed criminal elements into demonstrations, but many younger activists saw the statement as a regime-sponsored ploy to stifle protests of any sort. “Their statement was just like the government’s line—‘Stop protesting, you are causing fitna,’” said a local activist.

For their part, older Shia activists and intellectuals admire the youths’ zeal, but lament their lack of a program and organization. An attempt to unite disparate groups in the East into a “Freedom and Justice Coalition” has largely floundered. Further, the plethora of Facebook pages for other groups belies a degree of structure and coherence that does not actually exist on the ground. Some criticize youths’ naiveté in thinking that localized dissent by a sectarian minority can spark a Tahrir-style movement; “We are a minority, we are a province, we can’t spark a revolution,” noted one. Others disagree, pointing out that the demand for the release of political prisoners—originally started in the East—has become a national, cross-sectarian movement; Sunni activists in the Salafi stronghold of Qassim have since mounted concerted protests demanding the release of outspoken clerics. Young Shia activists argue that, whether they acknowledge it or not, these Sunni figures are actually inspired by the outspokenness and protest culture of the Eastern Province.

Others from the older generation applaud the youth as “post-ideological” and largely non-sectarian in their demands; they reject Iran’s revolutionary dogma and generally eschew the arcane juridical debates among the various Shia marjas (clerical sources of emulation). In conversation, several youth even regarded Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani as their preferred marja precisely because he stayed out of their political affairs; one even went so far as to characterize him as a “secular marja” (marja ilmani).

In conversations with Shia youth across the province as well as with older activists, there is an intense willingness to engage with Salafi reformists and clerics across the Kingdom. Much of this takes place beyond the purview of the regime’s officially sanctioned “dialogue” forums, which many activists perceive as a means to regulate and circumscribe any sort of coordination on actual reform. For example, a group of Shia youth recently launched a Twitter campaign to invite Sunnis from Jeddah to a celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birth. “They all thought we spoke Persian here,” joked one longtime activist in the East. A similar outreach, known as the Tawasul al-Watani, has been ongoing for nearly four years.

Despite these efforts, though, outreach has stalled because of the entrenched sectarianism in Saudi society and government policy. Many Salafi reformists remain tepid about associating too closely with Shia. With no one is this more apparent than the immensely popular and provocative Salafi cleric, Salman al-Awda, who has publicly hinted at democratic reforms, largely abandoned sectarian discourse, and even received Shia delegations. But local Shia lament that he has stopped short from an effective collaboration for fear of alienating his Sunni base. “The growing respect between Sunnis and Shia has not translated into collective action,” acknowledged one activist in Qatif. “We’ve done all we can; it is up to the Sunni reformists now.”

The reverberations of Syria on Saudi society have not helped reform coordination. As the officially sanctioned clergy frame the civil war in sectarian terms—demonizing the Alawis—the Shia of the Eastern Province have likewise come under increased pressure. Many are believed to sympathize with the Assad regime, despite the fact that Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, perhaps the most outspoken of the Shia clerics, has called for the downfall of Bashar. The statements of Syrian (and Iranian) officials have not helped matters; these governments typically speak about the affairs of the Eastern Province to advance their own self-serving regional agendas. For example, in March of last year, the Syrian delegate to the United Nations proposed sending Syrian troops to protect the population of Qatif after the Saudi delegate suggested Saudi troops should be sent to Syria to stop the massacres against the Syrian people.

As the two-year anniversary of what is locally called the “Eastern Revolution” approaches, it is unclear what (if anything) has really changed since March 2011. True, the government has taken some token steps to dampen sectarianism and “protect national unity”—including shutting down TV channels that spouted anti-Shia rhetoric, appointing an additional Shia MP to the non-elected Shura council, and building an interfaith dialogue center in late November 2012 (in Vienna, Austria, a revealing indication about the limits of dialogue inside Saudi Arabia). Most importantly, however, the longtime governor of the Eastern Province, Prince Muhammad bin Fahd, was removed from his post, which he had held since 1985. Among local Shia, the governor was widely known as “Mr. 50/50” for his alleged personal cut of local contracts—an appellation that, tellingly, is also applied by Bahraini activists to that country’s kleptocratic prime minister, Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa. While Muhammad bin Fahd’s removal was greeted with local applause, many activists remain pessimistic about real change, noting that Eastern Province policy is centrally directed from Riyadh—from the Ministry of Interior, in particular—rather than at the governorate level.

Finally, many in the province point approvingly to a sweeping investigation into the disturbances of the East published last year by the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies and leaked to an opposition website. Based on extensive interviews, the 125-page document is remarkable for its objectivity and detail in identifying the roots of dissent in the Eastern Province as an entrenched social, economic, and political problem—rather than as the usual explanations of criminality or Iranian-assisted subversion. “It is Saudi Arabia’s own Bassiouni Report,” noted one Shia activist in Safwa, referring to the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry. Sadly though, the document may suffer a similar fate as its Bahraini counterpart; it seems unclear as to whether or not Saudi authorities have the power—or even the will—to act on its recommendations.

Frederic Wehrey is a senior associate in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This article is based on information gathered during his visit to Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province in January 2013. His book, Sectarian Politics in the Gulf: From the Iraq War to the Arab Uprisings will be published by Columbia University Press later this year.