In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

{

"authors": [

"Kirk H. Sowell"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Sada",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Jordan",

"Levant"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

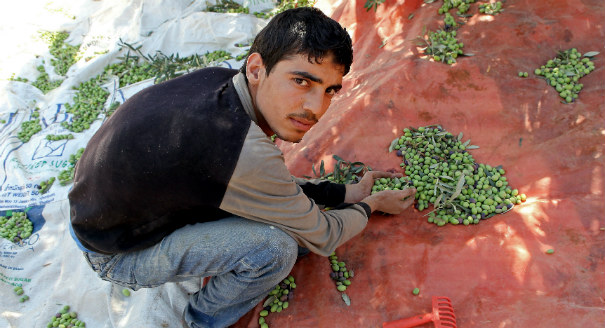

Source: Getty

Jordan is making a concerted effort to address unemployment by restricting foreign labor and promising increased vocational training.

Jordan’s government, headed by Prime Minister Hani al-Mulqi, is taking on labor market reform. It is fighting decades of dependence on foreign labor while producing ever more college graduates in the near-absence of vocational education. With the debt-to-GDP close to 100 percent and the state solvent only because of foreign aid, the government has determined to nationalize its workforce to address the dire issue of employment.

The depth of Jordan’s unemployment problem cannot be overstated. Prior to 2015, the Ministry of Labor only reported unemployment at around 12 percent, raising these reported rates to 18 percent by mid-2017, yet this still understates the problem as surveys only count those who self-report. A different way of looking at the issue is to compare new entrants to the labor force, which are more reliably counted, to new jobs created. As of 2017, Jordan’s universities produce 61,000 new graduates, but total net new jobs each year since 2011 average just 48,000. The Ministry of Labor’s 2015 job creation figures show just 16,000 of new jobs went to those with any education beyond high school. A separate survey published in August 2017 confirms these numbers, finding that only 34 percent of new college graduates find jobs within six months. This shortfall can only be partially attributed to the post-2011 economic downturn. Even in 2009, when universities were producing 40,000 graduates per year and Jordan created 76,312 new jobs, only about 28,000 went to those with post-secondary education.

Taking workforce participation into account deepens the gap. Women make up about 56 percent of university graduates but have a participation rate of just 13 percent in the job market. While there are many women graduates who would not be in the workforce for family reasons, others are absent due to a lack of jobs. Even male participation among Jordanian citizens remains low, at 58 percent. According to the World Bank, the global average is 76 percent—only seven other countries have male participation rates this low. The low participation rate for males is potentially explained by “the culture of shame.” The majority of private sector jobs available tend to be low-skill labor in manufacturing, retail, and agriculture, and these tend to be associated with low status, a result of long-term dependence on foreign labor without being wealthy.

Jordanians with a high school degree or less, who are most likely to pursue low-skill jobs and account for almost two-thirds of the population, are squeezed from below by competition from a large pool of foreign workers willing to work at lower wages. Jordan has over 300,000 registered foreign workers plus traditional estimates of 300,000-500,000 illegal foreign workers, making non-Jordanians 27 to 33 percent of the country’s total workforce—a large figure for a developing country with high unemployment. In December 2016, Minister of Labor Ali al-Ghazzawi said that the ministry estimated that there were now 800,000 illegal foreign workers, which if accurate would make foreigners 40 percent of the workforce. In February 2017, the ministry revised the estimate up to one million illegal workers, making them 44 percent of the total. Moreover, outgoing remittances come to $1.5 billion annually, cutting Jordan’s net gains from incoming remittances in half.

The private sector produces too few jobs for Jordanians even without foreign workers, so some degree of nationalization is unavoidable. For 2015, the last year for which the Ministry of Labor has made these statistics available, three of the six sectors that created the most jobs—civil and security services, education, and health and human services—were predominately in the public sector. The three private sector segments that produced the most jobs were retail, manufacturing, and hotels and restaurants, which in 2016 employed a reported 24,472; 83,052; and 17,686 foreign workers, respectively. While manufacturing initiatives such as the Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs), which are tied to a free trade agreement with the United States, are often held up as a success for dramatically increasing Jordan’s textile exports, the fact that a majority of the workers are from South Asia means this program has done little for Jordanian employment.

Therefore the new government has made the nationalization of the labor force its first major reform. On June 28, 2016, barely a month into office, the Ministry of Labor blocked new foreign worker permits, except for domestic workers and QIZ employees. The new minister of labor, Ali al-Ghazzawi, defended it as necessary not only to employ more Jordanians, but also to limit the large number of unlicensed workers. While Egyptian workers, who for decades have been heavily involved in Jordanian agriculture, have been given the option to renew their permits after six months, the ban on new permits effectively caps their current numbers, which will decline because the government increased the cost of the permit from 120 dinars ($170) to 300 ($420) for agricultural workers and 500 ($705) for other workers. Combined with a crackdown on the employment of foreign workers without permits, the policy promised to cut the supply of cheap labor while raising revenue.

The construction industry was quick to complain, saying as early as November 2016 that the restrictions on foreign labor had led to project shutdowns because Jordanians could not be found to do the work. Ministry of Labor Spokesman Mohammed al-Khatib responded that most unemployed Jordanians have similar education levels to foreign construction workers and that the restrictions in place for construction did not ban legal foreign workers, noting that the ministry’s enforcement mainly impacted “the 500,000-600,000” unregistered foreign workers.

The agriculture industry also complained that the measures increased the cost of labor from one-third of total costs to half. One farm owner interviewed by Al-Ghad said that he usually had to pay only 1.5 dinars ($2.10) per hour, but now workers were demanding 2 to 2.5 dinars ($2.80-3.50) per hour. Yet, unlike the construction sector, there was no reduction in work permits for agriculture, just a crackdown on the use of illegal workers. It is also worth noting that 2.5 dinars per hour is on par with the average salary in Jordan. By August 2017, with Jordan’s growing season in full swing again, employers again pressured the Ministry of Labor to allow more Egyptian workers whom they could pay less. Walid al-Faqir, head of the Water Management Initiative, argued that because Jordanians were refusing to take these jobs, the ministry was simply harming a sector already suffering from water shortfalls and reduced trade with Syria and Iraq.

Ghazzawi proposed getting Jordanians working in agriculture by having them do more mechanized agricultural work, promising in July 2017 to offer technical training to make sure Jordanian labor was productive enough to justify the higher cost. In addition, in September the government adopted a 100-million dinar ($141 million) program with two tracks, one focused on training and a second focused on placing Jordanians into industries that have heavily employed foreign workers. The goal is to reduce Jordan’s foreign workforce by 10 to 25 percent over five years.

These efforts coincide with, and to an extent are undermined by, a commitment under the “Jordan Compact,” a February 2016 agreement with European countries, to increase legal employment for Syrian refugees in exchange for aid and trade deals that the Jordanian economy desperately needs. The compact aimed to issue 200,000 permits to Syrians over three years, starting with 50,000 by the end of 2016. While behind schedule, permits were up to 62,000 by September 2017. Syrian labor most directly competes with other foreign labor for low-skilled jobs, rather than with Jordanians, but Syrians are also taking many positions the government wants Jordanians to have. This gives rights to decent pay for Syrians who are already working, helping prevent abuse, but it squeezes Egyptian workers in particular and will complicate expanding employment for Jordanians.

After many years of delaying reforms, the Jordanian government is now acting on a conviction that it must fix the mismatch between available jobs and the skills of those entering the labor force and reduce dependence on foreign labor. Beyond the government’s efforts to nationalize the workforce—which have already placed undue burdens on key private sector industries and are limited by its international obligations to employ Syrian refugees—both officials and community leaders could work to change attitudes about vocational training and manual labor to deal with Jordan’s chronically high unemployment.

Kirk H. Sowell is a political risk analyst focusing on Jordan and Iraq. Follow him on Twitter @uticarisk.

Kirk H. Sowell

Kirk H. Sowell is the principal of Utica Risk Services, a Middle East-focused political risk firm.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

Iraq’s foreign policy is being shaped by its own internal battles—fractured elites, competing militias, and a state struggling to speak with one voice. The article asks: How do these divisions affect Iraq’s ability to balance between the U.S. and Iran? Can Baghdad use its “good neighbor” approach to reduce regional tensions? And what will it take for Iraq to turn regional investments into real stability at home? It explores potential solutions, including strengthening state institutions, curbing rogue militias, improving governance, and using regional partnerships to address core economic and security weaknesses so Iraq can finally build a unified and sustainable foreign policy.

Mike Fleet

How can Saudi Arabia turn its booming e-commerce sector into a real engine of economic empowerment for women amid persistent gaps in capital access, digital training, and workplace inclusion? This piece explores the policy fixes, from data-center integration to gender-responsive regulation, that could unlock women’s full potential in the kingdom’s digital economy.

Hannan Hussain

Hate speech has spread across Sudan and become a key factor in worsening the war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. The article provides expert analysis and historical background to show how hateful rhetoric has fueled violence, justified atrocities, and weakened national unity, while also suggesting ways to counter it through justice, education, and promoting a culture of peace.

Samar Sulaiman