July 2025

Dear friends,

It is gearing up to be an eventful summer for Africa policy in Washington, DC. In trying to track relevant developments, it often feels as though one is trying to catch a mist: you can see it everywhere, but it is also hard to grasp and it can obscure more than it reveals. Perhaps the fluidity of the situation points to how we need to set aside our priors and employ a different set of analytical tools?

The Africa Program was recently in Luanda, Angola, for the U.S.-Africa Business Summit, where some of the tensions within U.S.-Africa engagement were on full display. The American delegation, led by Ambassador Troy Fitrell, then Senior Bureau Official for African Affairs at the State Department, emphasized the administration’s shift from aid to trade and hailed the implementation of the U.S. Commercial Diplomacy Strategy for Africa wherein foreign service officers will be judged on their ability to facilitate commercial deals with host countries. This message, echoed by officials from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), USTDA, and EXIM, energized summit attendees. Yet African governments, particularly the new Chair of the African Union Commission, expressed grave concerns about the viability of strong commercial diplomacy in the face of the administration’s threat of reciprocal tariffs—which could impose rates exceeding 20 percent on around 11 African countries—as well as reports of an impending U.S. visa ban affecting approximately 25 countries. Since then, the U.S. has reduced non-immigrant visa validity for applicants from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Nevertheless, the summit was a dynamic convening of key stakeholders in U.S.-Africa economic relations attended by well over 2,700 delegates mostly from industry as well as government, think tanks and civil society from both sides of the Atlantic.

Still on summits: last week, most of the DC policy community scrambled to follow the impromptu White House “summit” with the leaders of five West and Central African countries: Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania, and Senegal. News about the multilateral lunch meeting broke barely a week prior. While media coverage fixated on President Trump’s unusual remarks about the Liberian president’s spoken English—eliciting strong reactions from some African intellectuals—there were other developments worth highlighting. It appeared that both Trump and the African leaders were at ease, speaking a mutually intelligible language of lavish compliments and dealmaking. Substantive issues were also discussed: Gabon’s president emphasized the country’s endowments in critical minerals, its push for local value addition, and opportunities for U.S. investments. Senegal’s president invited U.S. expertise in conducting further geological surveys of its hydrocarbons and minerals endowments [read our policy brief on advancing U.S.-Africa partnerships in mining and geological sciences] and spoke about plans for a new tech city that could benefit from American capital. When asked about extending AGOA, Trump said “we will take a look at that”, he said “we will treat Africa very nicely” on tariffs and added that he might be interested in visiting the continent. All five African presidents agreed to a journalist’s proposal to nominate President Trump for a Nobel Peace Prize for his role in conflict resolution between the DRC and Rwanda and elsewhere around the world.

Interestingly, most journalists present asked questions unrelated to U.S.-Africa policy or international relations. This divergence is a pattern at White House briefings, where the media portion often strays from the core agenda. Watch the entire video replay. Reports suggest that behind the scenes, U.S. officials asked African leaders whether they would accept third-country deportees from the U.S. At a public event at the Atlantic Council the next day, Guinea-Bissau’s president and one of the summit’s architects Umaro Sissoco Embaló stated that no such discussion about “accepting immigrants” took place.

Meanwhile, the Africa Program was unable to attend the Fourth International Financing for Development Conference in Sevilla, Spain, focused on reforming the international financial architecture and mobilizing resources to meet the SDGs. Call it summit fatigue, maybe? Check out Devex for a readout. Besides, there is just so much happening in DC as the administration continues to drastically reposition America’s role in the global economy and multilateral system in ways that deeply affect the African continent. Frankly, so much of the development finance architecture is still being reorganized or dismantled anyways, that I am not confident in any solution emerging within the next year.

And on that note, the turbulence in U.S. international trade policy continues. On July 8, the Trump administration postponed, yet again, the implementation of reciprocal tariffs on all trading partners until August 1, to allow more time for bilateral deals. Since then, the White House has sent individual tariff letters to about 26 countries, including Algeria, Libya, South Africa, and Tunisia, with new reciprocal import duty rates. Unsurprisingly, many governments (including some African ones) have been dispatching delegations to Washington, while ambassadors are busy negotiating. So far, only the U.K., Vietnam, and Indonesia have struck “trade deals” with the administration. African countries face some of the steepest proposed duties, with Lesotho confronting a 50 percent tariff—a threat to over 40,000 jobs and the survival of its apparel industry. [Read Kholofelo Kugler and Tani Washington’s analysis of how African countries are responding to U.S. reciprocal tariffs.]

These emerging trade deals are not conventional agreements, which typically take years to negotiate. Rather, the new deals as we see from the ones with U.K. and Vietnam focus on a narrow set of product lines and are explicitly transactional: in exchange for lower U.S. tariffs, partner countries agree to increase imports of American agricultural goods or industrial equipment, or ease regulatory restrictions. For many African countries, particularly commodity exporters, their key bargaining chip will be critical minerals. For others, it may be their willingness to accept third-country deportees. A U.S.-DRC minerals deal is currently in the works. As I explain in this short video, the recent U.S.-Ukraine minerals deal may offer insights into how similar deals with African countries could be structured. The Africa Program plans to convene a series of roundtables on these minerals deals—with industry, trade experts, and governments—and will publish research in the coming weeks. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, China is advancing its own trade diplomacy. At the 4th China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo (CAETE) in Changsha, Hunan, from June 12–15, China announced a zero-tariff policy for imports from all 53 African countries with which it maintains diplomatic relations. The goal is to help close Africa’s $62 billion trade deficit with China. Whether African countries can capitalize on this opportunity is uncertain, given longstanding non-tariff barriers—such as electricity shortages, weak transport infrastructure, and compliance challenges with food and safety standards—that have similarly hampered their utilization of the U.S. preferential trade program, AGOA.

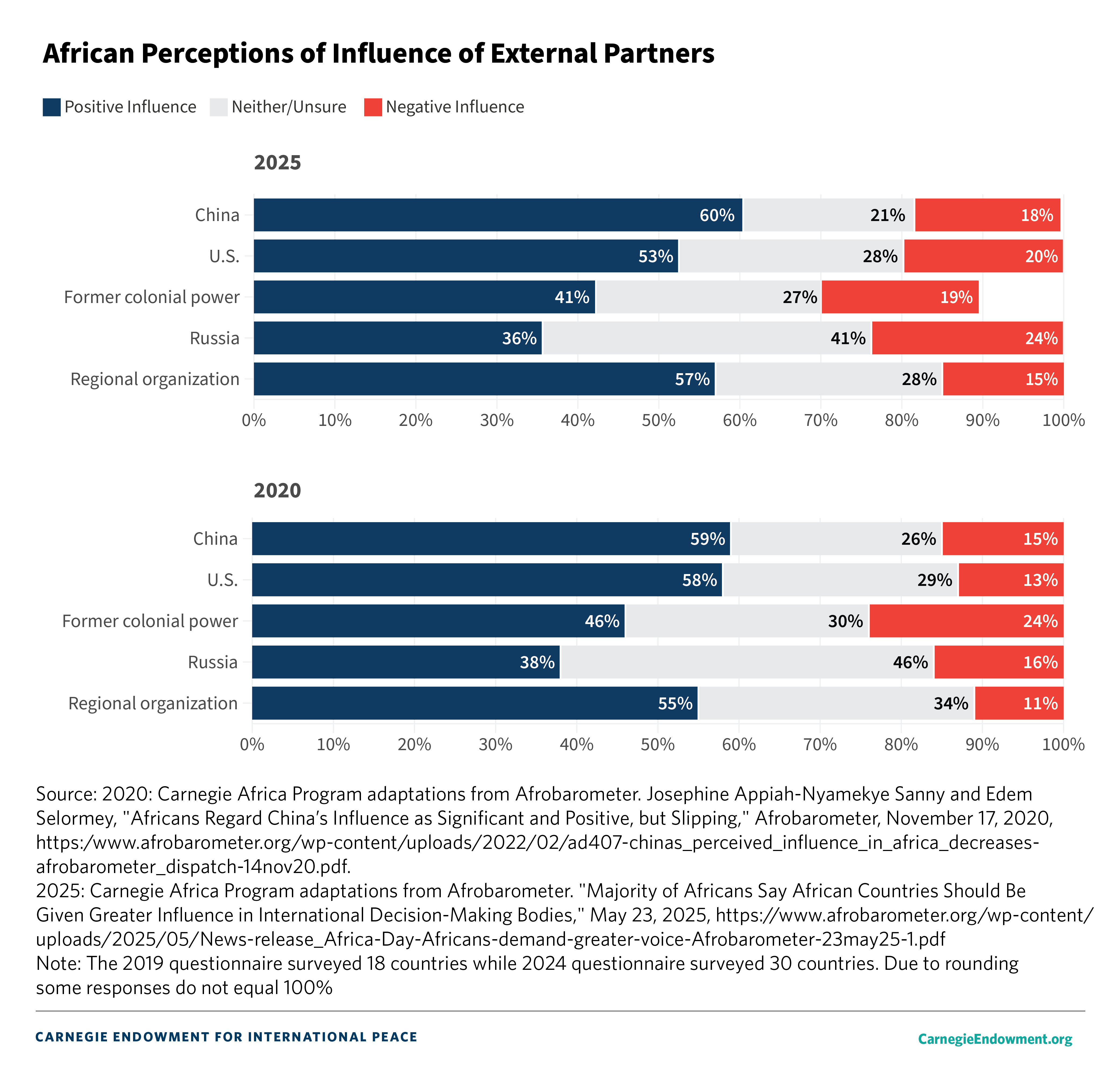

Still, China’s announcement gives it a narrative win, especially when juxtaposed with U.S. efforts to restrict African market access. It is therefore not surprising that China now ranks higher than the U.S. in African public opinion. In the Afrobarometer’s survey round 10, countries were asked: Do you think that the economic and political influence of each of the following countries or organizations on [country] is mostly positive, mostly negative, or haven’t you heard enough to say? As a result, 60 percent of Africans view China’s influence positively, compared to 53 percent for the U.S. and 49 percent for the European Union. These perceptions have shifted since 2020, with ratings rising by 1 percentage point for China (59%) and a 5-point drop for the U.S. (58%). (See our July Chart of the Month below.)

Elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific, Japan is preparing to host the Ninth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD 9), from August 20–22. Since 1993, the Japanese government has convened this summit in partnership with the United Nations, UNDP, the World Bank, and the African Union Commission. We will be keeping a close eye on this year’s TICAD.

Back in Africa, Kenya has been rocked by weeks of violent protests over police brutality and poor governance, leaving dozens dead. President William Ruto came into office in the summer of 2022 with a promising agenda to jumpstart the economy and fill the regional leadership vacuum left by countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and the DRC, all struggling with internal crises. In June 2024, Kenya was designated a Major Non-NATO Ally of the U.S. during Ruto’s state visit; the country also hosted an African Climate Summit and entered into trade talks with Washington. Today, however, much of that international goodwill has dissipated. See Jane Munga’s commentary on the recent protests and Professor Ken Opalo’s deeper analysis of Kenya’s political economy. Kenya’s relationship with the U.S. may also shift, especially following Ruto’s recent trip to China, where he described Kenya and China as “co-architects of a new world order”—a statement that has drawn criticism from the U.S. Senate.

Check out the professional opportunities – jobs, fellowships etc. – that we have included at the bottom of the newsletter.

This is our final newsletter for the summer, but we will see you again in September. Until then, enjoy the season. And, as always, stay connected by subscribing to our newsletter, follow us on LinkedIn, and find us on X (formerly Twitter) at @AfricaCarnegie.

Sincerely,

Zainab Usman

Director, Carnegie Africa Program

Features

How the U.S.–Ukraine Critical Minerals Deal Will Shape Future Partnerships

In May 2025, the Trump administration signed a groundbreaking agreement with Ukraine, focusing on critical minerals and postwar reconstruction. This video breaks down the key provisions, objectives, and global implications of the deal.

By Zainab Usman

How a U.S.-Africa Business Summit Could Launch a New Era of U.S.-Africa Relations

By shifting away from traditional aid delivery systems, a U.S.-Africa business summit could launch a new era of U.S.-Africa relations in a way likely to yield growth and shared prosperity.

By Ramsey Day

How Different Regions Are Rethinking Their Approaches to Subsea Cables

This critical infrastructure’s governance and security varies from region to region, and great power dynamics are one of the factors shaping investment, deployment, repair, and resilience.

By Sophia Besch, Jane Munga, Elina Noor, Erik Brown

How African Countries Are Responding to the New U.S. Reciprocal Tariffs

As African countries face different impacts from the tariffs and offer different responses, a cohesive trade strategy will be necessary to support individual economies and expand the continent-wide integration project.

By Kholofelo Kugler and Tani Washington

The End of the Global Aid Industry

USAID’s Demise Is an Opportunity to Prioritize Industrialization Over Charity

By Zainab Usman

Developments on Our Radar

Africa Now Has Duty-Free Access to the China Market, Now What? [China Global South Project]

Kenya: Visa-free travel now available for many African and Caribbean countries [AfricaNews]

Sidi Ould Tah elected ninth president of the African Development Bank Group [African Development Bank Group]

Why Gulf States are targeting African mines [The Africa Report]

Nigeria honours ex-President Buhari with state burial and tribute [Aljazeera]

Professional Development Opportunities

The Atlantic Dialogues Emerging Leaders Program 2025 [application]

Gulbenkian Institute for Advanced Study - Fellowships 2026/27 [application]

SOAS University of London - Research and Communications Fellow [application]

SOAS University of London Future Leaders Programme [application]

World Bank Group Africa Fellowship Program [application]

Boeing Visiting Faculty Chair in International Relations, 2025-2026 - Schwarzman Scholars [application]

Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor - Schwarzman Scholars [application]

Full-Time Faculty - Schwarzman Scholars [application]