Soon after the U.S. election results became clear, European leaders sent hasty congratulations to President-elect Donald Trump. Days later, when they gathered in Budapest for the European Political Community Summit and an EU meeting on competitiveness, Trump wasn’t on the agenda. But he was on everyone’s minds.

A Trump administration is still ten weeks away, but European politicians are already bracing for impact—a few with delight and a majority with anxiety. Getting Europe ready is the marching order, on issues that span climate, the economy, and security.

The first expectation after Trump’s inauguration on January 20 is a U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate. It happened under the first Trump administration, and it almost certainly will happen again. Europeans dislike it, but they are powerless to block the exit. Trump will fulfill a campaign pledge, underline a strong difference with Europe, and further hinder progress on climate.

Following in short order will be a salvo of protective trade measures, such as increased tariffs on cars, machinery, wines, cheeses, and other goods. This campaign promise was popular with Trump’s base. However, the intricate nature of international trade and investment makes it complicated to translate into policy. For example, would a German BMW assembled in Spartanburg, South Carolina, or a European Airbus A320 assembled in Mobile, Alabama, be considered foreign or American for tariff purposes? Given the intensity of U.S.-EU trade and investment relations, a salvo of U.S. tariffs on EU goods—followed by EU retaliations on U.S. goods—would bring adverse consequences for both America and Europe.

The most important issue for Europe is by far the U.S.-NATO-Ukraine-Russia nexus, because a U.S. policy drastically altering NATO and its Article 5 provision would have profound consequences for European security. Such changes would not only affect the future of Ukraine and European NATO members, but would also degrade America’s standing worldwide and perhaps encourage Russia to make further assertive moves in Europe.

Within NATO, Trump will want “delinquent” European governments to pay their fair share of the North Atlantic alliance’s budget. This thundering demand should not be too contentious, since the process is already underway. However, a reduction of U.S. funds for NATO, a withdrawal of U.S. troops and equipment from the European continent, or a sharp drop in U.S. economic assistance to Ukraine could all pose major threats to European security. Such drastic policy changes would normally require both a solid consensus within the Beltway and thorough consultations with European allies. The U.S. defense industry might also object on the basis of preexisting supply contracts. More generally, such decisions would weaken Trump’s hand in his future discussions with Russian President Vladimir Putin on ending the war against Ukraine and would signal weakness to Iran and China.

Trump has declared his intention to end the war in Ukraine “in a day,” though he has yet to offer details. An attempt to hastily achieve a Trump-Putin bilateral deal on peace in Ukraine would be met by strong opposition not only from Kyiv, but also from a majority of European members of NATO, with the exception of countries maintaining a close relationship with Moscow, such as Hungary. “Trump Stopped the Ukraine War in One Day” would certainly be a flashy headline, but a workable consensus on the modalities, legalities, and monitoring of such a momentous agreement cannot be accomplished in twenty-four hours—unless the goal is to give in to all of the Kremlin’s demands.

Beyond these key initiatives, a second Trump presidency may carry a more pernicious influence in Europe, where hard-right political forces that, to various degrees, show sympathy for both Trump and Putin are on the rise. The most vocal champion of these groups is Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, but similar beliefs can be found in governments in Czechia and Slovakia, and among political parties in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. By virtue of its flamboyant style and proclaimed policies, a second Trump administration will provide a boost to populist forces in European countries.

Trump’s immigration policies may have the most substantial influence on these groups. Irregular migration patterns in the United States and Europe have very different characteristics, including geography and countries of origin, but that may not matter to European populists. Hence, the president-elect’s widely publicized intention to expel irregular migrants will comfort European governments already pursuing restrictive measures of a similar nature—at the EU level or bilaterally, such as in Denmark, France, Germany, and Italy. The fact is that these preoccupations are similar and have become a major political feature on both sides of the Atlantic. European anti-immigration forces will relish Trump’s narrative and policies.

A second Trump presidency may also complicate the EU accession process of countries such as Moldova, Serbia, and Ukraine, depending on how U.S.-Russia talks develop. Their accession could suddenly become so complex that an alternative form of relationship would have to be invented. The concept of a European political community distinct from the European Union already exists—crucially, it includes the United Kingdom—but it would need to become institutionalized. It could also include Türkiye, where the constitutional architecture and rule-of-law choices have long rendered EU accession impossible.

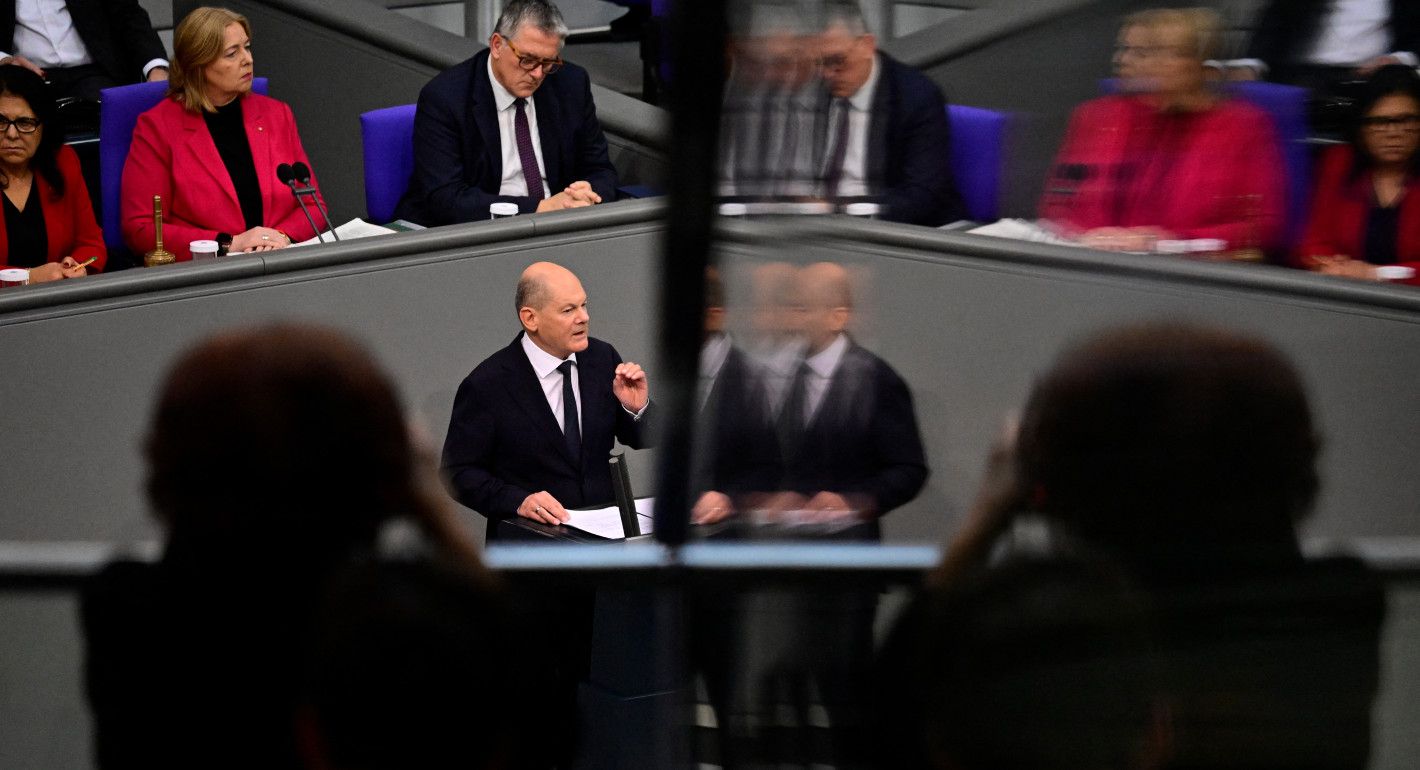

If many of Trump’s policies were to be actively supported by some EU governments, the world could witness a considerable reshuffling of the EU itself, because fundamental EU principles would also be at stake: rule of law, good neighborly relations, common foreign policy. Safeguarding the EU’s founding pillars would clash with populist pro-Russia proclivities within Europe, leading to momentous political battles on the future of the European continent, where the United States and Russia could possibly end up on the same side. European leaders—starting with France’s Emmanuel Macron, Germany’s Olaf Scholz, the United Kingdom’s Keir Starmer, and Poland’s Donald Tusk—cannot prepare themselves fast enough.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.