The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

{

"authors": [

"Stewart Patrick"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"The Post-American World"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "GOI",

"programs": [

"Global Order and Institutions"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Climate Change",

"AI",

"Technology",

"Democracy"

]

}

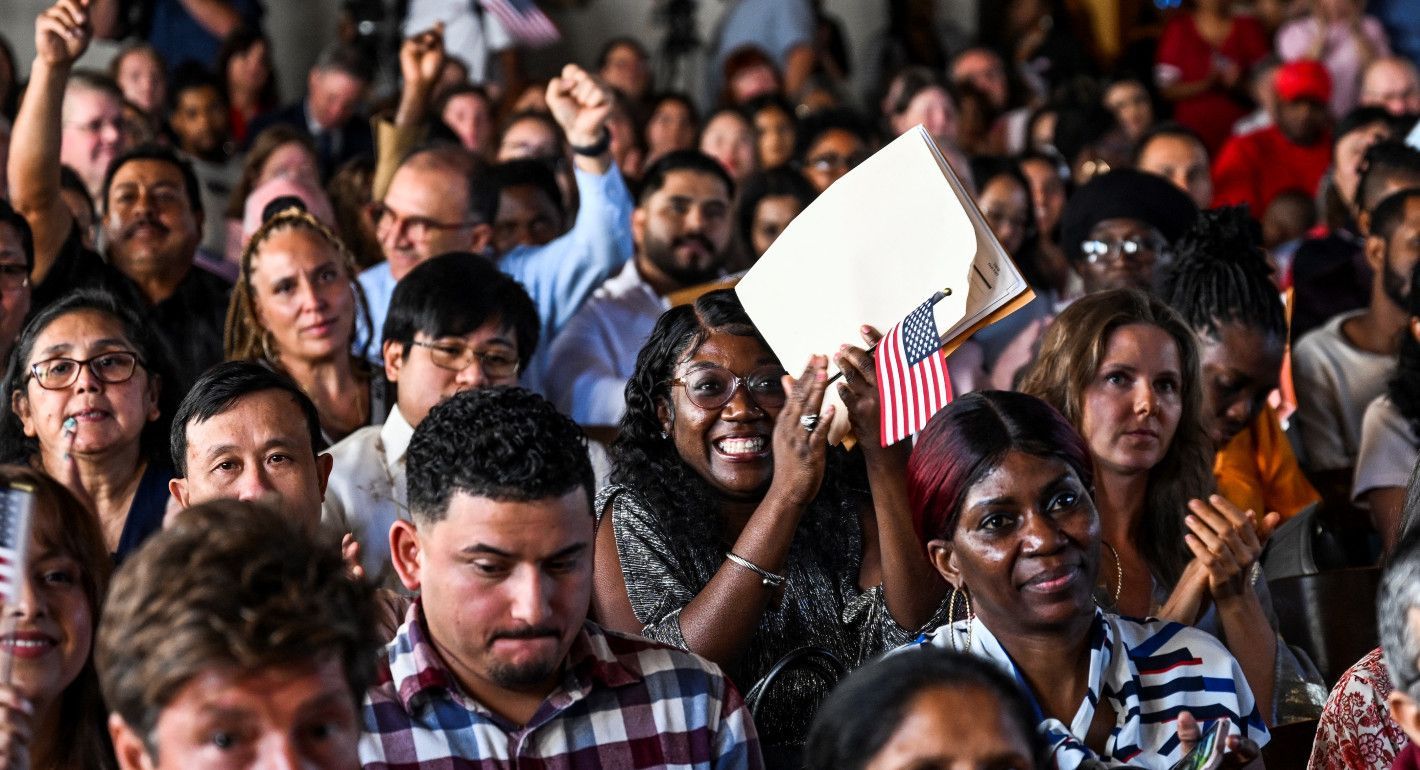

New U.S. citizens in Plains, Georgia, in October 2024. (Photo by Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images)

The incoming administration would be wise to reconsider some of its operating assumptions.

When President-elect Donald Trump enters the White House for a second time on January 20, he will encounter three mighty megatrends. Powerful demographic, ecological, and technological forces have dramatically reshaped the world since he entered office for the first time in 2017. Each of these forces runs counter to and threatens to overwhelm the policy preferences that the president-elect and his senior advisers have articulated, most notably when it comes to migration policy, climate change, and artificial intelligence.

To avoid colliding with these hard realities, the incoming administration would be wise to reconsider some of its operating assumptions, so that it can go with rather than against these powerful currents. Safely navigating the shoals ahead—and exercising true sovereignty over America’s destiny—will require the forty-seventh president make commons cause with other countries and pursue U.S. interests within international institutions.

The first megatrend is a demographic mismatch between a world that is simultaneously old and young, but in different places. In 2023 the world’s population topped 8 billion, up from just 5.3 billion in 1990. It will continue to grow for several decades before cresting between 9.7 billion and 10.9 billion later this century. But in the wealthy world—and even some developing countries—the main worry is not overpopulation, but depopulation, as birthrates plummet and societies age rapidly. In Italy, the fertility rate today is just 1.24 births per woman—far below replacement. In South Korea, it is 0.72—meaning that if trendlines hold, the country’s population will decline 95 percent by 2100. Even China has recently seen its population peak, at about 1.4 billion. Many aging countries face a fiscal cliff, lacking enough workers to cover the expenses of pensioners who are living longer and healthier lives.

Meanwhile, Africa will see its population nearly double by 2050, when one in every four people on Earth will be African. This could be an economic boon, provided the continent’s governments and the global economy can deliver opportunities rather than disappointment to what is already the world’s youngest continent. Thanks to changing fertility and mortality rates, the world’s demographic “PIN code” is set to shift dramatically. A decade ago, it was 1-1-1-4—with approximately 1 billion people apiece living in the Americas, Europe, Africa, alongside 4 billion living in Asia. By 2100, thanks to surging population growth in Africa (and continued, modest growth in Asia) the code will be 1-1-4-5.

One obvious response to this demographic mismatch is higher legal migration from poor but youthful to rich but aging nations. But the politics of this are toxic in much of the world, with migrants becoming easy scapegoats for nativist demagogues. During his first term in office, Trump sought to curtail not only irregular but also legal immigration (not least from African countries), despite the importance of such inflows for staving off U.S. demographic decline. The most recent Republican Party platform calls for him to do so again, even as the U.S. fertility rate has tumbled to 1.62 children per woman. In late December, Trump’s billionaire advisers Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy advocated increasing H-1B visas issued to high-skilled immigrants, outraging Trump’s base. But even if that number grows, it will be far too modest to solve America’s demographic decline and do nothing to meet market demands for low-skilled labor. “To sustain economic growth,” the Washington Post reckons, “the United States needs an infusion of a few million immigrants every year.”

Absent significant immigration, Americans must somehow be persuaded to have more babies—an avowed goal of Vice President-elect J. D. Vance. However, the track record of pronatalist policies is poor, and it is unclear what credible incentives the Republican Party is willing to put on the table to encourage larger families. That being the case, one thing seems clear, as demographer Nicholas Eberstadt writes: “In the shadow of depopulation, immigration will matter even more than it does today.”

The second megatrend is the deepening planetary emergency. Last year was the hottest on record—and likely the coolest we will ever again experience. As the latest Emissions Gap Report notes, the world is badly off track in meeting its 2015 Paris Climate Agreement aspirations. To hold the rise in average global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius, nations must cut emissions 42 percent over the next five years and 57 percent by 2035—targets that now seem totally implausible. The planet currently is on course for a 2.6 to 3.1 degree Celsius temperature rise during this century.

This climate overshoot will guarantee even more catastrophic wildfires, droughts, heatwaves, hurricanes, floods, and other supercharged disasters. Already, the oceans are warmer than at any time in the past 100,000 years—when sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher—and 30 percent more acidic than just 200 years ago, in the early Industrial Revolution. Critical components of the Earth system, from the Amazon rainforest to the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to the Atlantic Ocean current that keeps Europe temperate, are nearing dangerous tipping points. Crossing these thresholds will bring about even more abrupt and discontinuous changes that themselves will accelerate climate change.

Biodiversity is also collapsing, jeopardizing the copious benefits that humans get from healthy species and ecosystems, from the insects that pollinate crops to the mangroves that protect coasts and nurture fisheries. This is not about tree hugging but about what’s in your wallet. According to the World Economic Forum, half of global GDP depends on so-called ecosystem services. But rather than investing in natural capital—as they do human capital (like health or education) or physical capital (like roads and ports)—modern societies despoil it.

This dire trajectory calls for a massive mobilization, akin to the Manhattan Project or Apollo Program, to accelerate investments in decarbonization and natural capital, accompanied by economic incentives and regulations to foster a nature-positive economy. The administration of President Joe Biden took initial steps in this direction, most notably through the Inflation Reduction Act. Trump, in contrast, still dismisses the “climate hoax” and promises to double down on fossil fuels. Trump’s positions won’t alter scientific reality, the same way Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ injunction that state officials strike the phrase “climate change” from public documents won’t alter scientific reality. What they will do is make the hole humanity has dug itself even deeper.

The third megatrend is accelerating technological innovation, including in artificial intelligence and synthetic biology. While these advances hold immense promise, they also pose exceptional risks, and it is unclear Trump is attuned to the need to mitigate these through national regulation and international cooperation.

When Trump took office in January 2017, few outside Silicon Valley had heard of large language models (LLMs), and Nvidia’s share price hovered around $2.50. AI has since exploded, with an estimated 70,000 AI companies worldwide, and Nvidia’s share price was just under $138 at the time of publication. Four of the largest technology firms—Microsoft, Meta, Alphabet, and Amazon—are anticipated to spend a quarter-trillion dollars on AI in 2025, and the global AI market is expected to grow sixfold by 2030. Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, LLM capabilities of have improved dramatically, with many anticipating the imminent advent of artificial general intelligence.

These breakthroughs have enormous potential social benefits, including for advancing scientific discovery, alleviating poverty, revolutionizing education, improving healthcare, streamlining government services, combating climate change, and enhancing worker productivity. Yet without safeguards, expanding AI capabilities could generate massive unemployment, facilitate disinformation, enable mass surveillance, violate privacy rights, exacerbate inequality, undermine arms control, accentuate great power rivalry, and even threaten human extinction.

A parallel revolution in the gene editing and synthetic biology, itself turbocharged by AI, presents a similar mixture of promise and peril. The positive applications of CRISPR Cas-9 technology—from curing afflictions such as sickle cell anemia to improving agriculture—appear limitless. But generative biology will bring unprecedented biosecurity and biosafety risks, allowing adversarial governments and terrorists to create new or resurrect old pathogens as biological weapons, as well as increasing the likelihood of accidents.

Historically, technological innovation has often outpaced governance efforts. Today, commercial and geopolitical concerns are lengthening this lag, increasing safety and security risks from technologies that are inherently dual use and prone to unintended consequences. Not two years ago, thousands of technologists warned that AI companies were “locked in an out-of-control race to develop . . . ever more powerful digital minds that no one—not even their creators—can understand, predict, or reliably control.” Such worries have since been brushed aside, as firms compete to reap financial gain and the U.S. government races to best China as the dominant AI power.

Mitigating such risks requires robust domestic oversight and enhanced international cooperation. Neither goal, however, is a major priority for Trump, whose election was backed by technology “accelerationists.” David Sacks, Trump’s incoming AI czar, is a critic of tech regulation, suggesting that the new administration will remove the modest, existing guardrails in favor of industry self-regulation. Trump will surely rescind Biden’s executive orders on AI, which his party claims “hinders AI innovation and imposes Radical Leftwing ideas.” Trump will likely intensify U.S. AI competition with China while abandoning Biden’s bilateral dialogue on AI safety with Beijing.

Dramatic demographic shifts, a deepening environmental crisis, and accelerating technological innovation are powerful megatrends that no single person, not even the president of the United States, can reliably control or alter in the short and medium term. What Trump can do is try to navigate these currents as effectively and safely as possible and, where possible, shape their long-term trajectory.

Trump should respond to U.S. demographic decline by crafting a balanced immigration policy, in coordination with hemispheric governments, that simultaneously deters irregular entry and expands pathways for legal immigration, which remain the life blood of the U.S. economy. He should reassert rather than abandon U.S. global climate change leadership and double down on existing federal incentives and regulations to promote the clean energy transition, confident in the capacity of U.S. firms to compete in the postcarbon economy. Finally, he should enhance government oversight of private AI companies that cannot be counted on to act in the public interest, while reaching out to America’s long-standing U.S. allies, including in the European Union, to develop common international standards for AI grounded in Western values.

In seeking to Make America Great Again, Trump will need to try to ride the waves of global megatrends rather than fight, in vain, against them. Otherwise, he risks becoming a modern-day version of the Persian King Xerxes, who, when stormy seas destroyed his fleet and his best-laid plans, ordered the waters to be lashed.

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan