Researchers from China have long been one of the largest contributors to cutting-edge artificial intelligence research at American companies and universities. Studies of the top AI research papers have shown the authors originally from China contributing as much—if not more—to American AI output than authors from the United States.

But the past seven years of escalating U.S.-China tensions have raised a new question: Are these U.S.-based Chinese AI researchers now returning to China en masse? Put more sharply, is the United States training researchers who will go on to build the AI capabilities of its top geopolitical rival?

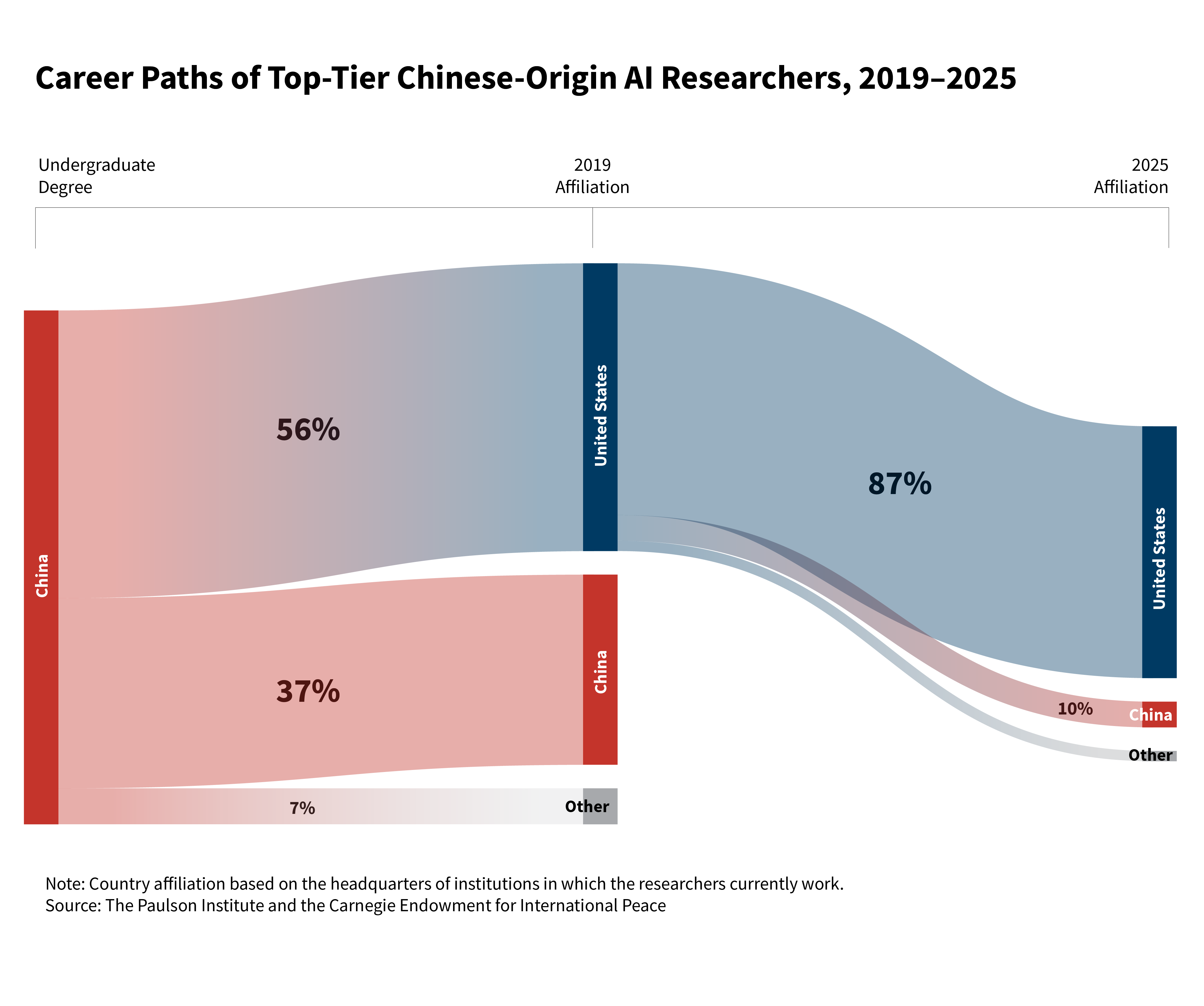

To answer that question, we leveraged and updated a unique dataset from a 2020 study by the Paulson Institute: The Global AI Talent Tracker. (Matt Sheehan was one of the authors of that study.) That dataset contained a sample of 675 top-tier AI researchers who had their research papers accepted at perhaps the world’s top AI conference, NeurIPS 2019 (which has an acceptance rate of about 20 percent). The data showed where these researchers had completed their undergraduate degrees (a rough proxy for country of origin), where they went to graduate school, and where they worked at the time. Within that sample of 675 researchers, exactly 100 of them were Chinese-origin researchers doing research at U.S. institutions as of 2019. To assess whether the United States has retained this pool of top AI talent, we recently gathered updated information on where those 100 researchers work today.1

Eighty-seven of them remain at U.S. institutions. Only ten left to work for Chinese companies or universities, with the remaining three affiliated with institutions in other countries.

This is good—and perhaps surprising—news for U.S. AI competitiveness. Historically, Chinese researchers who came to the United States for their PhDs have had very high stay-rates, with around 90 percent remaining in the country long term. But amid mounting U.S.-China tensions over the past five years, studies have documented a sharp rise in the number of Chinese-origin researchers, across many disciplines, who chose to leave the United States and return to China. Set against this backdrop, our data on Chinese-origin AI researchers showcases the enduring attractiveness of the United States as a place to work at the frontiers of AI.

But reasons for concern remain. Although the data shows America’s ability to retain top AI researchers who are already here, there are some signs that America’s ability to attract Chinese talent is waning. Though this data is limited, it appears that a larger share of talented Chinese AI researchers are simply choosing to remain in China rather than come to America in the first place.

Obstacles to Staying, Reasons for Leaving

In recent years, a number of high-profile, Chinese-born AI researchers have made a splash when they decided to leave the United States and return to China. The reasons why any individual researcher returns home are varied and often personal. But the recent geopolitical tumult has created new obstacles and pressures for Chinese researchers who want to remain in the United States.

Beginning in 2018, a series of actual and proposed restrictions on student visas—including discussions of an all-out ban on Chinese students—left many Chinese researchers in limbo. Chinese applicants faced long delays in processing visa renewals, making them uncertain whether they would be able to finish their degrees and remain in the United States to work. Many who did stay said they felt a cloud of suspicion cast on their work by U.S.-China technological tensions and accusations of industrial espionage.

A series of high-profile indictments of Chinese researchers in the United States sent chills through these communities, but many of those cases collapsed upon further investigation. In a 2021 survey of university researchers who self-identify as Chinese, 42 percent reported feeling racially profiled by the U.S. government. In conversations with Chinese engineers and researchers during this time, several described instances in which U.S. customs officials confiscated and searched the electronic devices of them or their friends and colleagues.

Travel restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic further curbed incentives and opportunities for Chinese researchers coming or returning to the United States. In February 2020, the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump barred entry for foreign nationals who had been in China within the previous two weeks, and China followed up with its own restrictions on inbound travel in March. Even after China officially reopened its borders in 2023, flights between the two countries remained scarce, with daily flights still less than 30 percent of the pre-pandemic levels today.

In addition to these obstacles to remaining in the U.S., China’s AI industry is also exerting a stronger pull on researchers who have gone overseas. Just five or ten years ago, if someone wanted to work at the global forefront of AI research, the opportunities to do that in China were quite limited. But today, Chinese companies and universities have rapidly caught up in pathbreaking research and the training of frontier AI models, giving these researchers the chance to do this work without moving halfway across the world and operating in a second language.

Who Stayed and Who Left

Despite these new push-and-pull factors, the vast majority of researchers from the dataset chose to continue working for U.S. institutions six years later. During the intervening years, many of them moved from U.S. universities into the private sector.

Of these eighty-seven people, forty-one of them currently work in U.S. companies, forty hold professorships at U.S. universities, and six are either completing doctoral degrees or in postdoctoral research positions. Of those working for U.S. companies, more than half are employed by the Magnificent Seven (Google, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla), with others lending their talents to some of the top American AI startups. Three of the eighty-seven founded their own startups in the United States.

Although only ten out of the 100 researchers returned to work for Chinese institutions, those who did return tended to be very high-impact. Two founded their own startups, two took on leadership roles in AI-focused tech giants, and five became professors at some of China’s top universities.

One of the returnees is Yang Zhilin, a star researcher who completed his undergraduate degree at Tsinghua University in 2015 before heading to Carnegie Mellon University for his PhD in computer science. At Carnegie Mellon, Yang was the lead author on widely cited research papers co-authored with some of the world’s most influential AI researchers. In 2023, Yang returned to China to found Moonshot AI, a company whose Chinese name (Dark Side of the Moon) is an homage to Yang’s favorite album. Moonshot has since raised more than a billion dollars and released the Kimi model series, producing some of the world’s top-performing open-source (OS) models. Many U.S. startups are now adopting and building on top of Kimi and other Chinese OS models such as Alibaba’s Qwen. In explaining the decision, they often cite a combination of performance and cost-efficiency in Chinese models that aren’t available from the closed, proprietary models released by American firms such as OpenAI and Anthropic.

Yang’s path highlights the ways in which—despite intense geopolitical rivalry—the Chinese and American AI research communities remain deeply intertwined, connected through rich cross-border flows of people, ideas, and now leading AI models.

Missing the Next Generation

Although the United States has managed to retain a large portion of Chinese AI researchers over the past six years, there are signs that it has lost some of its ability to attract new arrivals from China—a potentially ominous trend given China’s share of global AI talent.

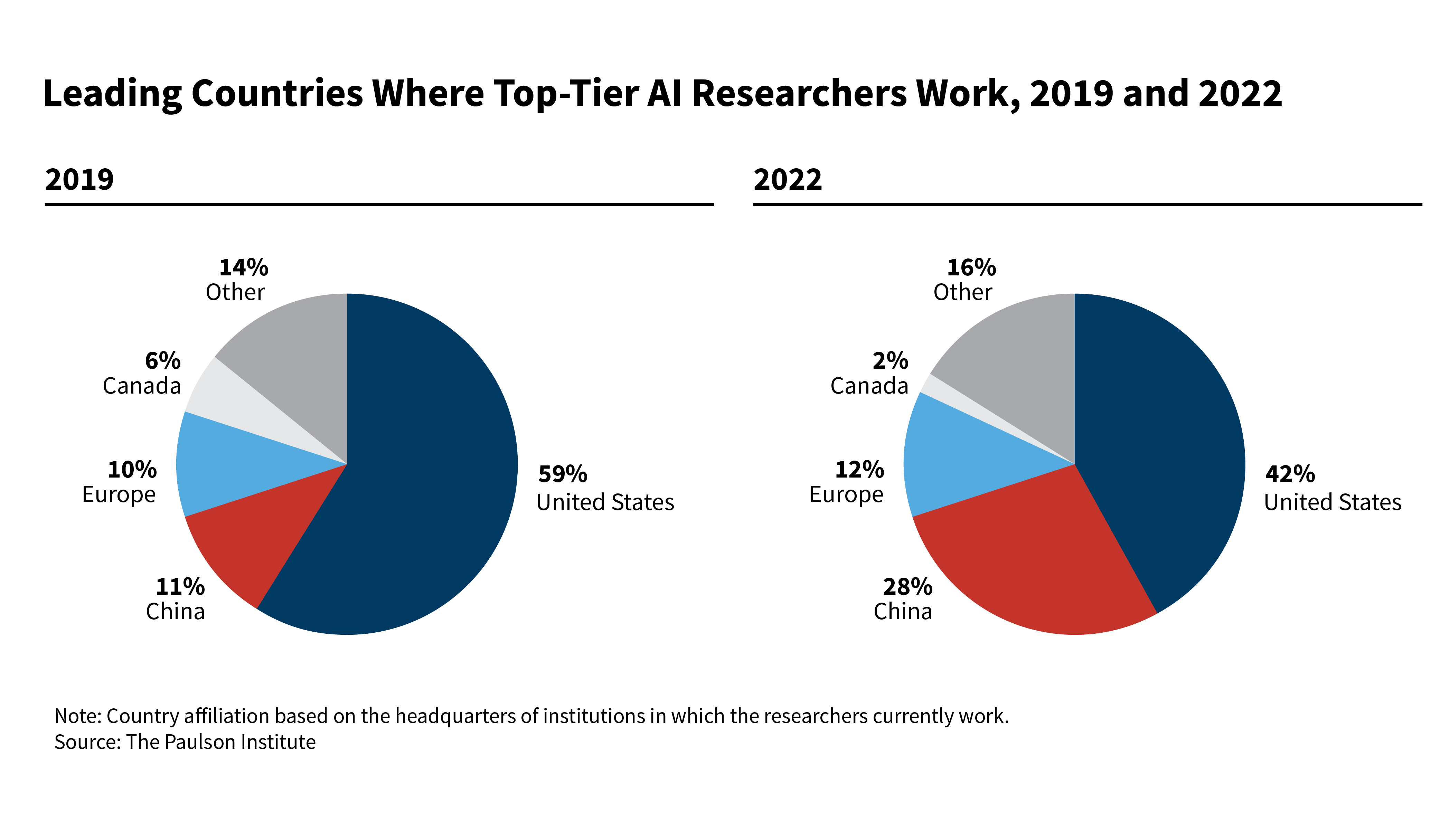

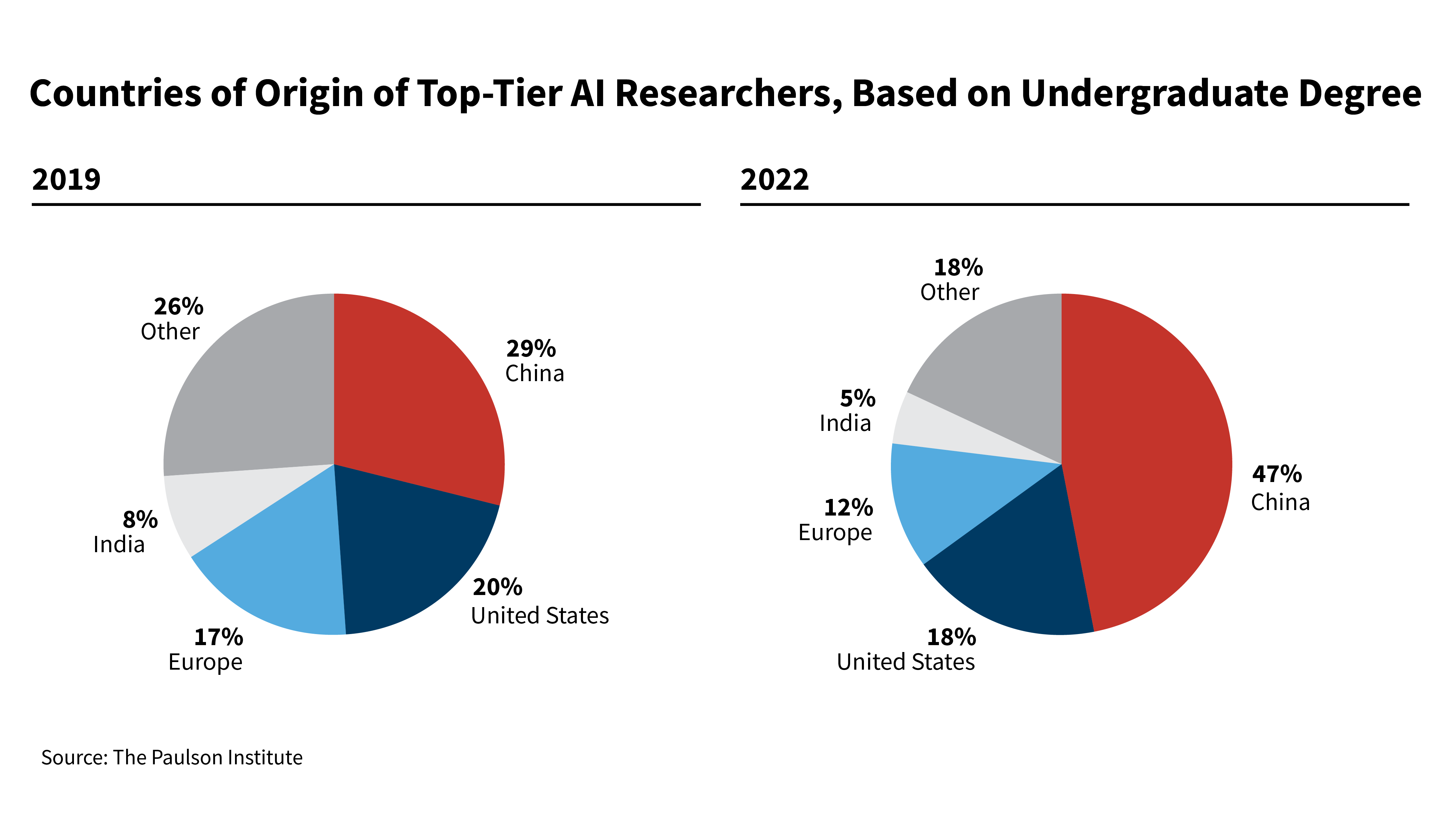

The original Global AI Talent Tracker drew its data from researchers whose papers were accepted at NeurIPS 2019. At the time, Chinese-origin researchers made up 29 percent of the authors of papers at the conference, surpassing the U.S. share of 20 percent and Europe’s 17 percent. Fortunately for the United States, the majority of those Chinese-origin authors (as well as researchers from around the world) chose to do their research at U.S. institutions. Looking at the 2019 affiliation of these 675 top-tier researchers, 59 percent worked at U.S. institutions, compared with 11 percent for China, and 10 percent for Europe. Of the researchers who completed undergrad in China, 56 percent were studying or working for U.S. institutions, compared to 37 percent in Chinese institutions. Looking at all of the researchers who were working at U.S. institutions, 31 percent had completed undergrad in the United States, followed by 27 percent in China, and 11 percent in Europe and India respectively.

Three years later, the Paulson Institute re-ran the study using authors of papers at NeurIPS 2022. By that point, Chinese-origin researchers made up nearly half of all the authors sampled, and Chinese institutions had more than doubled their share to 28 percent. That was still well short of the U.S. share of 42 percent, but it demonstrated rapid catch-up by China in producing many of the year’s best AI research papers.

It also suggested that a larger share of these top-tier Chinese researchers were choosing to remain in China instead of coming to the United States. The 2022 study doesn’t provide numbers on what percentage of these researchers who attended undergrad in China remained in the country for graduate school and to work, but it notes that more Chinese-origin researchers were choosing to stay in China.

If left unchanged, these trends—a larger share of top-tier researchers originating from China, and a smaller portion of those researchers coming to the United States—don’t bode well for U.S. competitiveness. Over several decades, the United States has accumulated a huge number of elite researchers who came from China but chose to live and work in the United States long term. If that flow of talent stops—or even worse, is reversed—the United States will be left scrambling to try to train and attract enough talented researchers to fill the void.

An “All of the Above” Strategy

The United States maintains many advantages when it comes to building and deploying the world’s most advanced and most productive AI systems. It has a major edge over China in access to the cutting-edge chips used to train and run AI systems. Despite the rapid rise of some Chinese apps, American tech giants such as Google and Meta have far larger and more diverse global user bases, giving them inroads into markets and insights into users that their Chinese peers lack. But one of the strongest long-term advantages of the U.S. AI ecosystem—the world’s best pool of research and engineering talent—is at risk.

Mitigating those risks requires an “all of the above” strategy to train, attract, and retain world-class AI researchers. It requires increasing investment in U.S. high schools so that Americans have the tools to begin working in AI. It requires providing the research grants and certainty around visas that help attract the world’s best international students to pursue graduate studies here. And it requires fostering an environment such that the most talented AI researchers from around the world—including China—want to live and build their careers in the United States. None of these things are easy, but the path forward—and the stakes of success or failure—are clear.

Notes

1Methodology: This paper draws on and updates data from The Global AI Talent Tracker, first published in 2020 by the Paulson Institute. (The original study is available in archived form here.) The 2020 study drew on data about the authors of research papers accepted at one of the most prestigious and selective AI conferences, NeurIPS 2019. The study randomly selected 175 papers from 1,428 accepted papers at the conference and collected data on the 675 authors and co-authors of those papers. Using publicly available sources, including LinkedIn and personal or academic websites, the study gathered data on the authors’ undergraduate universities and countries, graduate universities and countries, and 2019 affiliations and countries, as well as the countries where their institutions are headquartered (for multinational corporations with research facilities around the world). The full methodology for the 2020 study is available in archived form here. In the sample of 675 researchers, exactly 100 obtained their undergraduate degrees from Chinese universities (what we classify as “Chinese-origin researchers”) and either studied or worked at U.S.-headquartered institutions in 2019.

For this study, we gathered updated information on the 2025 affiliations of these 100 Chinese-origin researchers using the same methods. The new dataset included information on their 2019 and 2025 institutional affiliations (including where those institutions are headquartered), and whether their current positions are in industry or academia. For people with more than one affiliation—often holding both private-sector positions and university teaching titles—we used the affiliations under which they published new research as their affiliation. In cases where researchers published using both affiliations, we looked at their personal websites to make determinations on which affiliations were “primary.”