A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

{

"authors": [

"Michael Young"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Syria in a New Era"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Syria",

"Israel"

],

"topics": []

}

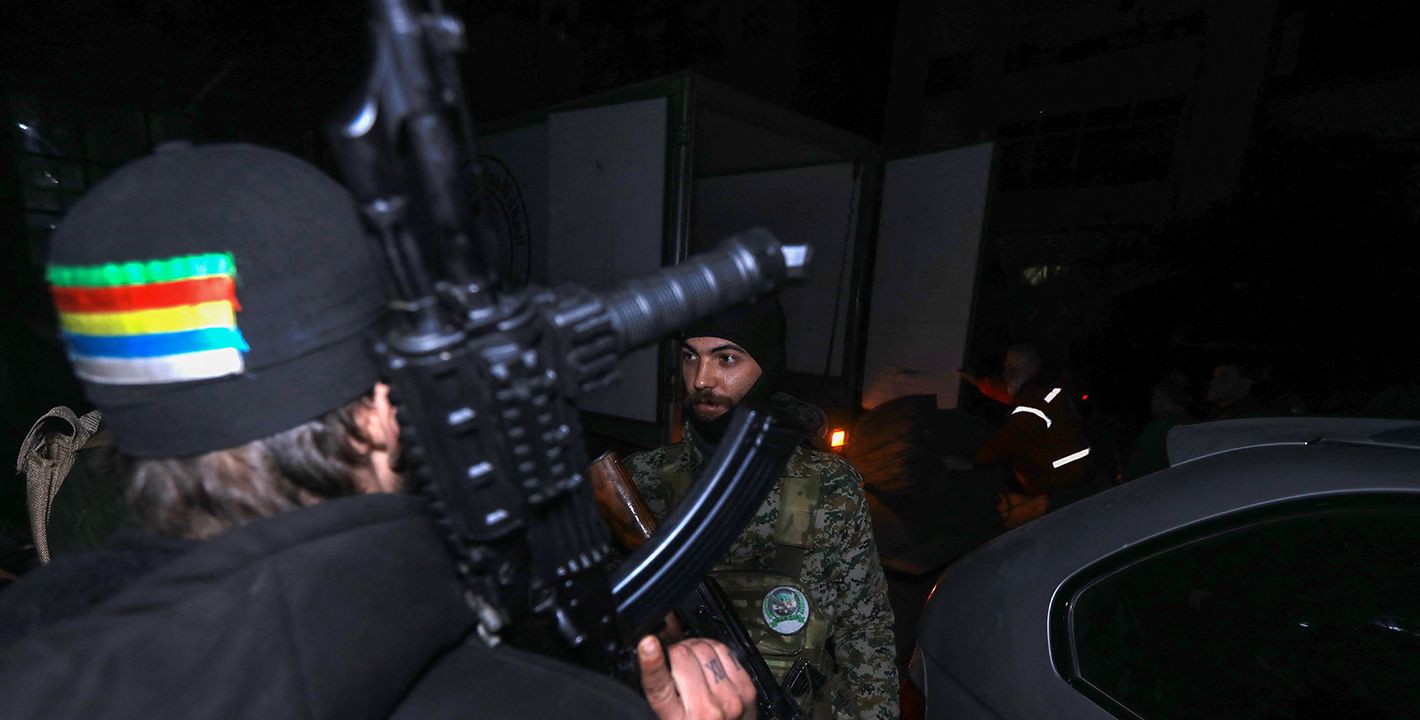

Source: Getty

Israel’s actions in Syria appear to favor the country’s fragmentation into sectarian and ethnic entities.

As the Syrian regime apparently seeks to impose a Salafi-inspired order on a pluralistic society, Israel has seen an opening to advance its geostrategic interests in the country and create a situation that leads to Syria’s partition. There appears to be little pushback from the United States, most likely because the Americans regard Israel as an extension of their power in the Middle East. However, if the Trump administration favors regional stability, Israeli actions, if successful, may lead to precisely the opposite.

Last week, after fighting broke out in the Damascus suburb of Jaramana, which is populated mainly by Druze and Christians, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that Israel would intervene to protect the Druze if regime forces attacked them. Defense Minister Israel Katz declared that the government was “committed to our Druze brothers in Israel to do everything to prevent harm to their Druze brothers in Syria.”

This came shortly after Netanyahu had stated that southern Syria, where large numbers of Syria’s Druze are concentrated, had to be completely demilitarized. “We demand the complete demilitarization of southern Syria in the provinces of Quneitra, Deraa, and Sweida from the forces of the new regime. Likewise, we will not tolerate any threat to the Druze community in southern Syria,” Netanyahu told Israeli cadets on February 23. On March 9, the Israelis went further in their efforts to tie Syria’s Druze to Israel. Katz announced they would be allowed to enter the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights to work.

In parallel with this, Israeli officials have continued to express support for Syria’s Kurds. Last December, Israel’s foreign minister, Gideon Sa’ar, noted that the international community had to protect the Kurds from Turkish attacks, declaring, “It’s a commitment of the international community toward those who fought bravely against [the Islamic State group]. It’s also a commitment for the future of Syria, because the Kurds are a stabilizing force in this country.” The Kurds clearly heard the message. Earlier this month, a senior Kurdish leader, Ilham Ahmed, the co-chair of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the self-declared Kurdish-controlled zone in Syria, told Israeli media, “The security of the border areas in Syria requires everyone to be engaged in the solution, and Israel is one of the parties to that. Its role is going to be very important, so having the discussion with Israel at this time is very important.”

All this came as Syria’s interim president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, was facing mounting tensions with his country’s minority communities. Last week, news that former Assad regime groups had organized attacks against Syrian security forces were quickly overwhelmed by reports of massacres of over 700 people, mainly Alawites, by gunmen tied to Sharaa’s regime. As one diplomat told the French journalist Georges Malbrunot, “The wind has started to shift for Sharaa, who made the mistake of rapidly alienating the minorities after having brought Assad down, instead of having them as partners. But now, it’s probably too late.”

For the Israelis, the fragmentation of Syria, and surrounding Arab countries, would be a boon. Not only would such an outcome guarantee that Israel’s neighbors remain weak, it would also mean, in Syria’s case, that there is no credible government to challenge Israel’s illegal annexation of the Golan Heights. Debilitated Arab states also open other doors, not least that Israel could engage in the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian population by pushing them into nearby countries, with little resistance. Such are the benefits of Israel’s plan for Syria, which is to see the country partitioned along ethnosectarian lines, allowing the Israelis to establish buffer zones near their own borders, or zones of influence elsewhere.

Not that this is particularly new. Britain and France after World War I also manipulated minority politics to divide Arab societies and enhance their control. For a time, the French broke Syria up into supposedly autonomous sectarian entities, establishing Druze and Alawite statelets, allowing them to undercut Syrian nationalist impulses. Similarly, France allied itself with the Maronites in Lebanon and created the Grand Liban, where sympathy with France was more pronounced, as a way of strengthening its influence. That is why Israeli thinking today is very much in line with that of the European colonial powers.

There is a second dimension to Israel’s current approach. As the Israelis have tried to trigger Syria’s breakup, they have unilaterally imposed a security order of their own, whereby they can intervene militarily at will against potential threats. This has been visible almost daily in Syria and Lebanon, and in the Lebanese case was legitimized by the United States in a side-letter to the Israelis accompanying ceasefire negotiations last November.

The role of the United States in this evolving situation has been essential. During the conflict that followed Hamas’s October 7 attack against Israeli towns, the Americans largely embraced Israeli war objectives and armed Israel, despite the extremely heavy civilian loss of life in Gaza. When the conflict with Lebanon escalated in September 2024, the Americans continued to support the Israelis, imposing a surrender agreement that was charitably passed off as a ceasefire agreement, as well as expanding, through its side-letter, Israel’s latitude to pursue military operations without constraints. In every way, the Biden administration, and now the Trump administration, was or is complicit in Israeli actions.

If we assume that the Americans view Israel as a valuable regional policeman at a time when the United States is refocusing its attention on competing with China, this raises an intriguing question. Can Israel’s promotion of partition plans lead to stability in the Middle East—to a Pax Israelica that lays the groundwork for a peaceful regional order?

If that is the expectation, the Americans and Israelis may have to prepare for a rude awakening. Israeli hegemony cannot bring regional stability, because it is so reliant on Arab instability. For Israel to dominate in Syria, it must always ensure that local communities remain divided, since once they unify their efforts, they would be able to challenge Israeli power. At the same time, how often has religious or ethnic partition led to anything but violence? The cases of Palestine, India, Cyprus, or Bosnia-Herzegovina are all examples where partition led to unspeakable suffering, as communities sought to maximize their territory, and as minorities were ethnically cleansed. The late Christopher Hitchens wrote an essay on the perils of partition, in which he mordantly concluded, “A series of uncovenanted mandates, for failed states or former abattoir regimes, is more likely to be the real picture.”

Then there are the regional implications. A Pax Israelica may accelerate pulses in Washington, but in the Middle East it is certain to cause considerable dissatisfaction and blowback, as Israel’s leading rivals seek to undermine its neocolonial yearnings, in favour of their own. Türkiye and Iran are the two most obvious candidates for such an endeavor, and they would probably not be alone. As regional actors interfere in minority affairs to strike at a status quo benefiting Israel, the consequences are likely to come at the expense of the minorities themselves, who will be turned into expendable pawns in proxy wars.

One might argue that the Americans care little about such problems, and are not overly concerned with stability in the Middle East. But then again, their umbilical attachment to Israel, their wholehearted subcontracting of the regional order to the Israelis, would almost certainly mean that they would be drawn back into the region’s quagmires if they were to see their ally’s domination jeopardized. Yet nothing at all today indicates that the United States has any interest in again becoming entangled in the Middle East.

For a long period, the United States liked to portray itself as a democratic republic opposed to the imperial ways of European powers. Yet strangely enough, its habits in the Middle East since the end of the Cold War have been highly suggestive of how those powers once managed the Arabs. In Iraq, the Americans tried a particularly ham-fisted neoimperial revival under the stewardship of the so-called Coalition Provisional Authority and L. Paul Bremer; in Palestine, the Trump administration is now pushing for a beachfront version of population engineering once so beloved of the British during their empire; and America’s implicit acquiescence in Israel’s partition plans for Syria doesn’t seem so very different than an outlook that, had it been in place 109 years ago, might have endorsed Britain’s and France’s decision to carve up the Arab world in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.

More encouragingly, the Syrians themselves appear to be taking measures to avoid the dynamics of partition. On Monday, the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces agreed with the government of Ahmad al-Sharaa to integrate their forces into the country’s new government, thereby sidelining a potentially major conflict between Damascus and its Kurdish minority. A day later, the government came to a similar agreement with the Druze community in Sweida, which among other things will place Druze militias under the authority of the Interior Ministry. While this is good news, in the medium term much will depend on whether the Syrian government can consolidate a more inclusive order. Until then, the pull of partition will linger in the background, and Israel will be waiting.

A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

Implementing Phase 2 of Trump’s plan for the territory only makes sense if all in Phase 1 is implemented.

Yezid Sayigh

Israeli-Lebanese talks have stalled, and the reason is that the United States and Israel want to impose normalization.

Michael Young

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan