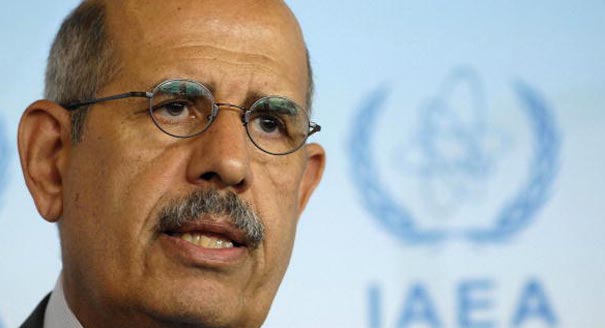

On Monday, Mohammed ElBaradei stepped down after twelve years as head of the UN's nuclear watchdog. Yukiya Amano, ElBaradei's successor as director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, will confront growing proliferation challenges from nuclear weapons programs and nuclear power industries across Asia, the Middle East, and beyond.

In the final days of ElBaradei's tenure, the last week of November, the IAEA issued a stern resolution censuring Iran for continually defying its international nuclear obligations. In response, Iran announced that it would build 10 additional uranium enrichment plants, once again challenging the IAEA's enforcement authority. In a new Q&A, James Acton reflects on ElBaradei's leadership, discusses Amano's agenda, and calls attention to the importance of the IAEA's work.

- How would you assess Mohamed ElBaradei’s twelve-year tenure as director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency? What were his successes and failures?

- How will Japan’s Yukiya Amano differ from his predecessor? Why did the United States favor his candidacy?

- How influential is the position? How do the director general and the IAEA impact states’ decisions to abandon, pursue, or proliferate nuclear capacities?

- How will Amano’s arrival impact international efforts to contain nuclear programs in Iran, North Korea, and Syria?

- How will Amano manage the proliferation challenges posed by an expanded use of nuclear energy?

How would you assess Mohamed ElBaradei's twelve-year tenure as director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency? What were his successes and failures?

Today's IAEA is a very different beast than the slightly obscure technical organization that Mohamed ElBaradei inherited 12 years ago. ElBaradei has raised the profile of the Agency considerably and more people and governments recognize that it is a vital component of the global nonproliferation architecture. Perhaps ElBaradei's defining moment was his very vocal argument, prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, that there was no evidence that Iraq had reconstituted its nuclear weapons program. This doubtless contributed to his 2005 Nobel Peace Prize.

Yet in the process, ElBaradei has also regularly stepped beyond his mandate. In the last few years, ElBaradei has come to view himself as global statesman. He has increasingly spoken about political issues ranging from the importance of nuclear disarmament to his views on sanctions on Iran and even the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Meanwhile, where states have violated their nonproliferation obligations, he has hesitated to use the full investigative authority of the IAEA and could have pressed states much more strongly to grant the IAEA swift access to nuclear sites by immediately reporting unnecessary delays to the IAEA's Board of Governors. However well-intentioned this approach has been, it has eroded confidence among many states, including non-Western ones, in the IAEA's ability to carry out its safeguards role impartially and effectively.

Behind the scenes, the IAEA Secretariat has also become increasingly politicized. In particular, the Office of External Relations and Policy Coordination (which reports directly to ElBaradei) is an increasingly important force in drafting reports to the Board of Governors. It consistently argues for "softer" language than that advocated by the Department of Safeguards, which leads the Agency's investigations.

Although safeguards are the Agency's highest profile task, the IAEA also works to promote the peaceful uses of atomic energy, especially in developing states. Particularly noteworthy was ElBaradei's initiative, "Programme of Action for Cancer Therapy," launched in 2004 to "improve cancer survival in developing countries by integrating radiotherapy investments into public health systems."

How will Japan's Yukiya Amano differ from his predecessor? Why did the United States favor his candidacy?

Yukiya Amano has positioned himself as a very different kind of leader than ElBaradei. He has indicated his desire to play a much less high-profile role and has spoken of the need to depoliticize the IAEA.

Amano's election was long and painful. His main rival was the South African, Abdul Minty, who is regarded as an "advocate" in the ElBaradei mold, and who gained support from developing nations. The United States and most developed nations supported Amano, in part because they believe that he is less likely to soft-pedal reports on Iran, but more generally because they believe that in long run he will be a less divisive leader.

How influential is the position? How do the director general and the IAEA impact states' decisions to abandon, pursue, or proliferate nuclear capacities?

The IAEA is tasked with verifying whether states are complying with their nonproliferation obligations. If it can fulfill this task effectively, it will help deter states from embarking on nuclear weapons programs in the first place. The IAEA must be well-funded and technically competent. Its nuclear verification budget for 2010 is only about €120 million ($179 million), of which the United States pays about 25 percent. Although this is a real-term increase over 2009, it is still very modest given the importance of the Agency's role. The director general has an important role to play, both in lobbying states to provide adequate funding and in ensuring that the Agency’s own internal procedures are effective.

Deterring states from embarking on nuclear weapons programs requires more than just verification; it also demands effective enforcement in the event that a state has been found to have broken the rules. This task largely falls on the IAEA Board of Governors and the UN Security Council. Whether states on these bodies support enforcement depends in part on the reports submitted to them by the IAEA director general. In this way the director general can certainly influence the enforcement process. Drafting honest, straightforward, and complete reports is one of his key tasks.

How will Amano's arrival impact international efforts to contain nuclear programs in Iran, North Korea, and Syria?

Iran will be the most pressing item in Amano's inbox when he takes office. The Agency's investigation into Iran's nuclear program is now in its eighth year. For over a year now, Iran has refused to meaningfully address evidence of nuclear weapons design activities that, in the words of Mohamed ElBaradei "appears to have been derived from multiple sources over different periods of time, appears to be generally consistent, and is sufficiently comprehensive and detailed that it needs to be addressed." Added to this is Iran's recent statement that it intends to build ten more centrifuge enrichment plants. While few believe that Iran has the resources to follow through, it underlines the hostile atmosphere in which the investigation is being conducted.

If Iran continues not to cooperate, Amano could deliver a more strongly worded report to the Board. This would increase the chance that the UN Security Council will agree to tougher sanctions.

Although not so high-profile, Amano will also have to make a decision about whether to change tactics in handling the Syria investigation. There is strong evidence that the building the Israelis destroyed in an air strike in September 2007 was a nuclear reactor that Syria failed to declare to the IAEA—in breach of its legal obligations. The IAEA has repeatedly asked Syria for access on a voluntary basis so it can investigate the matter further. Syria has consistently refused. Amano must decide whether to make the Agency’s request for access legally binding by asking for a "special inspection"—a step ElBaradei steadfastly refused to take.

As for North Korea, given that it has withdrawn from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), it has now largely fallen outside the Agency's jurisdiction. If the denuclearization process resumes, the IAEA will almost certainly be tasked with verifying the shutdown of North Korea's declared nuclear activities. That is a straightforward task and likely to prove uncontroversial.

How will Amano manage the proliferation challenges posed by an expanded use of nuclear energy?

The IAEA is already significantly underfunded and the further expansion of nuclear energy will stretch its budget yet further. Getting states to part with their cash has always been an uphill battle, and it will be a significant test of Amano's leadership.

Amano will also need to oversee the ongoing process of reforming safeguards to better address new challenges. For example, there is always a debate about whether the Agency should focus its limited resources on states with large nuclear power industries or those believed to present higher proliferation risks. Given that Amano hails from Japan, a state with a large nuclear industry that complains about the burden of safeguards, it will be interesting to see how he handles this debate.

Finally, there is an effort underway to create back-up fuel supply guarantees to enhance the energy security of states developing nuclear power. On November 27, the Board of Governors approved IAEA involvement in a proposal by the Russian Federation. Other proposals are in the pipeline. Managing the development and implementation of these mechanisms will be high on Amano's agenda and success could allow him to make an early mark.