Three thoughts on the revolution in Ukraine: first, it was as remarkable as it was unexpected. Nothing in Ukrainian public attitudes suggested that hundreds of thousands of citizens would rise up against the corrupt and oppressive government of Victor Yanukovych. He seemed firmly in charge, supported by the country’s business elite, the security services, as well as the cronies he had placed in key posts throughout the government. The strength, the organization, and the courage of the protest movement were unexpected, as was the collapse of the Yanukovych regime.

Second, Western media coverage of the revolution has been remarkably one-sided, focusing on Putin and Russia rather than on what was happening in Ukraine. The Economist newspaper called it “Putin’s Inferno” on its cover. The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote on Sunday about “The Games Putin Plays” rather than about the remarkable turn of events in Kyiv, and chose to discuss the limits of Russian power and influence. Even Zbigniew Brzezinski told Charlie Rose on February 20 that “in many ways the issue goes beyond Ukraine, it goes to the heart of the issue ‘what will Russia become over the next decade or so…’”

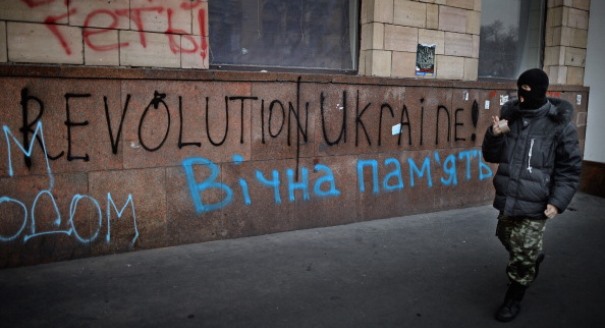

There is no question that Russia has played and will continue to play a very important role in Ukraine’s future. There is not question that there are regional divisions with the West leaning toward Europe and the East and South toward Russia. But the focus on Russia has ignored the fact that it was Ukraine’s revolution, made in Ukraine by Ukrainians. The country has been independent from Russia for nearly quarter of a century and has had its own political life, its own media, its own oligarchs, its own political class, its own business community and intelligentsia, had conducted multiple presidential and parliamentary elections—in other word has been independent of Russia. That will be the deciding factor in its future, and that is where—in Ukraine—the greatest uncertainty lies today.

Which brings us to the third point: the fall of Yanukovych’s government in Kyiv is only the beginning of a new and difficult chapter in Ukrainian history. It is a new chapter, but it does not begin on a clean sheet of paper. Instead, Ukraine begins this new phase with a lot of baggage. Its domestic politics is full of uncertainty. The three protest leaders—Vitali Klitschko, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and Oleh Tyahnybok—were united in their opposition to Yanukovych and put aside their differences during the struggle. Will they continue to cooperate now? How will they manage their political ambitions? Will they agree on a single candidate? Will they work together through the very difficult next phase with many tough and unpopular decisions to be made on the economy? They have talked about the need for economic reforms, but those are certain to be painful for Ukrainian voters and run counter to the interests of powerful business interests. Those are not easy for any politician running an election campaign.

Then there is the Tymoshenko factor. Her appearance in the Maidan after release from prison will probably be the most iconic image of the revolution, but her future role in Ukrainian politics is unclear. Along with her reputation as the fiery leader of the 2004-2005 Orange revolution, she carries her baggage as one of the key players in Ukraine’s notoriously shady gas trade with Russia—the “gas princess”—and a highly divisive politician whose falling out with then-President Victor Yushchenko was blamed by many for the failure of his presidency and the election of Victor Yanukovych in 2010.

It is hard to imagine that after Tymoshenko’s imprisonment by Yanukovych she has given up her political ambitions. How will she get along with the opposition troika? The new speaker of Ukrainian parliament-turned acting prime minister-turned acting president Aleksandr Turchynov is a long-standing associate of hers. Will she opt to concentrate on repairing her health but pull strings from behind the curtain? She has denied that she is running for prime minister. Indeed, who would want that job now, when the economy is described as “catastrophic” and tough decisions have to be made? But after the May election?

Looking beyond leadership politics, there is the challenge of national reconciliation. Anti-Yanukovich protests have spread through most of the country, not just its traditionally Europe-leaning West. But before the protests began support for the Association Agreement with the European Union was a lot weaker in the Eastern regions of the country, and the geopolitical tug of war between Europe and Russia over Ukraine has almost certainly accentuated these differences.

The first post-revolutionary signs are not encouraging. After his disappearance, Yanukovych briefly re-emerged and claimed the revolution was a coup, and he still considered himself to be the legitimate leader of the country. He then disappeared again. The gathering of politicians supporting Yanukovych from the country’s Eastern regions in Kharkiv was attended by Russian politicians. Although all spoke in favor of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, the threat of a split—certain to be very messy if it comes to that—is in the air, as are the questions of the whether and how of Russia’s role in it.

The new leadership, for its part, did not help matters either. One of the first actions by the Rada following Yanukovych’s departure was to repeal the 2012 law that had granted Russian the status of a second official language in those parts of Ukraine that had a significant share of Russophone residents. This is bound to feed the myth of Ukraine’s European aspirations as being anti-Russian.

The relationship with Russia is becoming more, not less complicated. The Russian government has recalled its ambassador from Kyiv for consultations—a worrisome sign against the backdrop of some very harsh statements by senior Russian officials and politicians questioning the legitimacy of the new government. Perhaps, most significantly, Putin has not made a public statement, which suggests a wait-and-see attitude on his part. The new Ukrainian leadership’s pledge to pursue European integration—no doubt welcome news to those in the Maidan—will reinforce Russian perceptions of the revolution’s anti-Russian essence.

Russia’s decision to—again—suspend its assistance to Ukraine underscores the dire economic situation in the country. Its acting president/prime minister Aleksandr Turchynov has declared that the treasury is empty and the government has no money to meet its obligations—to the pensioners, to the holders of the reported $13 billion of Ukraine’s sovereign debt, and to the military and security personnel. So far, no offers of aid to replace Moscow’s $15 billion loan package are forthcoming. The IMF has expressed its readiness to help Ukraine, but in the words of the IMF Chief Christine Lagarde “We need to operate under the rules and that means there are important economic reforms that need to be started.” Those reforms again, three months before the election!

Even in foreign policy, aside from the difficulties with Russia, Ukraine is facing the prospect of a complicated relationship with Europe. Having declared European integration its top priority, the new leadership is bound to be disappointed. Europe’s doors are not open. The Association Agreement that Yanukovych did not sign in November did not include a path to EU membership. The so-called free trade provisions of the deal are comprised of 15 chapters, 25 annexes, and two additional protocols—hardly a free trade document.

To paraphrase what many have said before, this is not the end, not even the end of the beginning, this is just the beginning. And a very messy one at that.