This piece is part of a Carnegie series examining the impacts of Trump’s first 100 days in office.

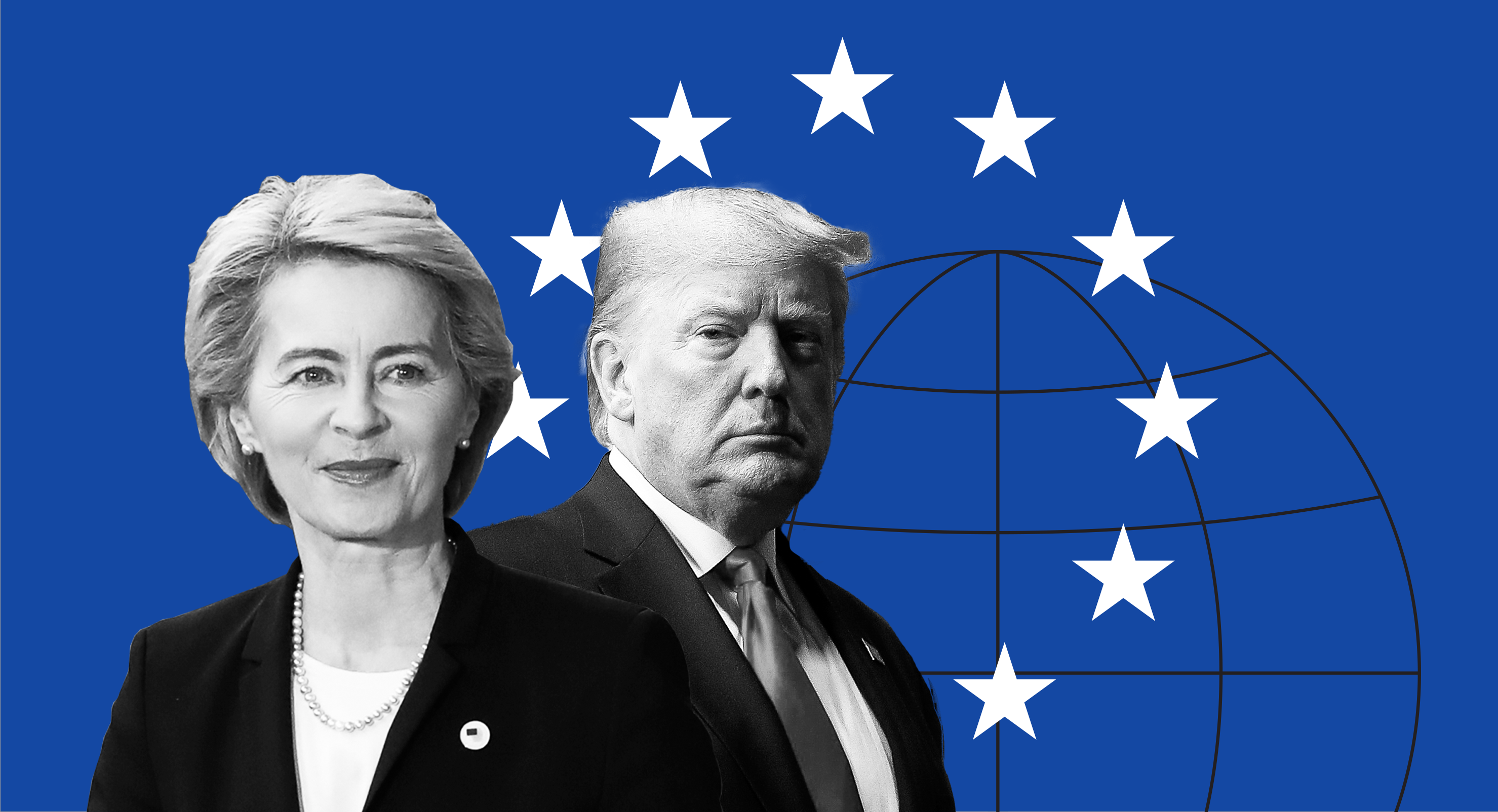

At some point between February 12, when U.S. President Donald Trump spoke to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and the televised humiliation of Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky on February 28, Europe realized it could no longer rely on its longtime ally, the United States.

The shocking depth and breadth of this realization cannot be overemphasized. Political leaders in European states, the European Union, and NATO displayed composure and coordination, but behind the scenes, the soundtrack was a frantic free jazz jam session with dramatic thuds and a long pause—the silence at the realization that the European comfort zone was over.

This revelation shattered the “Trump-proofing” preparations, which included a mix of appeasement, “cheque book diplomacy,” flattery, and moves to dodge direct hits. Some countries were—or thought they were—better placed to seek a relationship with the new president, but the U.S. administration has displayed widespread antagonism toward the EU. The deep entanglement between the two sides of the Atlantic (worth $9.5 trillion and 16 million jobs) means that the dramatic changes in policy have an existential impact on the continent. But the building blocks of a response strategy are coming into focus in three key areas.

First, Ukraine is Europe’s first line of defense. London and Paris have been convening a “coalition of the willing” to plot the next stages of European military and diplomatic support, with the goal of making Ukraine a “steel porcupine” in case of a ceasefire. In the absence of progress in the U.S.-Russia negotiations (and involvement of European countries in the talks), any evaluation of these efforts is premature. But the format enables a majority of European states to work together, despite the lack of cohesion at the EU level. The hope is that Germany and Poland (after its presidential election in a few weeks) will play key roles in this format.

The leadership of London and Paris underscores another important political point: The return of a Franco-British understanding on security and defense after nearly a decade of Brexit-related bickering over fisheries and migration marks a step change that can help reshape the relationship between the EU and UK.

EU institutions, especially the European Commission, also can play supporting roles by mobilizing financial resources and handling complicated in-house horse trading. Divisions among European countries continue to plague consensus-building in the European Council. With respect to Ukraine, the EU has been able to reach agreement with only twenty-six members, with Hungary continuing to hamper consensus and threatening to block imminent decisions on renewing sanctions against Russia or other measure to support Ukraine.

Second, the need for European states to increase their defense spending was long overdue, and the open discussion about assuming responsibility for territorial defense and deterrence is unprecedented. Governments are taking drastic measures to increase defense spending, with Germany’s U-turn on public debt as the most remarkable evidence that taboos can be broken. Alongside national decisions on how to raise defense spending to more than 3 percent of GDP—whether through taxation, cuts, or debt—several initiatives have been announced and others are being discussed to address how the EU can contribute to these efforts.

Aside from financing Europe’s security, the complexities of coordination between NATO, its members, and the EU is a major hurdle. But the real challenge is to overcome existing fragmentation in the defense industry and in procurement. Spending alone does not make Europe more capable of defending itself.

Politically, to ensure public support for rearming Europe and to offset the inevitable costs, defense efforts ought to be part of a broader strategy of economic and technological innovation. Indeed, these efforts could boost Europe’s stagnant economy. At the EU level, the recipes are available in recent recommendations addressing competitiveness, productivity, and technological innovation.

Indeed, Trump’s first 100 days are pushing the EU to put some momentum behind projects that have been underway for years. Tying these objectives with the enlargement of the EU to include Ukraine, Moldova, and the Western Balkans adds a new perspective to upscaling the single market. Expanding the EU and deepening the relationship with other European countries—like the UK, Switzerland, and Norway—would counter the fragmentation that great power competition and political disruption at home are inflicting on the continent.

The final building block of this response is a newfound penchant for global engagement as a means to diversify the EU’s economy and political relations. The tariff barrage unleashed by the United States has prompted a flurry of promises to pursue free trade deals with a range of partners across the globe. In February, after two decades of stagnating talks, the EU and India (re)discovered each other and agreed to finalize a free trade agreement by the end of 2025. At the end of 2024, the EU and Mercosur finalized a trade agreement. New opportunities are being discussed with the UAE, Malaysia, the Philippines, and others. The EU could act as a node in a global trade and cooperation network alternative to the United States’s unilateral protectionism.

Needless to say, the political will and resources to achieve these goals are hard to sustain. The economic and social costs of the security and economic transition at home will lead to political challenges in a volatile context in which few governments enjoy wide popular support, though the EU is enjoying positive public opinion polling at the moment—likely a silver lining of the Trump effect.

The EU’s security turn will come at the expense of its soft power, with reputational costs at home and abroad. Making its economy fit for geopolitical disruption entails daunting obstacles and difficult choices. Europe’s vulnerability to great power rivalry is compounded by disruptive political forces that embrace Trumpian world views. Transatlantic nostalgia could slow down the collective effort, should Washington revisit its current European stance. The armory of policy could fail. And the outcomes may not be to everyone’s liking.

Yet a trajectory of change has been charted, and it has transformative potential—not just for the European continent, but also for the global reordering of post-American international relations. The jazz band has picked up rhythm, even if the melody is not fully harmonic.

Read more from this series, including: