The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace hosted a media call on the crisis in Ukraine with Balázs Jarábik, Dmitri Trenin, and Andrew S. Weiss. They discussed the latest developments in the crisis, the planned referendum in Donetsk on May 11, and the elections on May 25.

LISTEN TO THE CALL.

TOM CARVER: Good morning, everyone. Welcome to the 9:00 media call on the Ukraine. We have Balázs Jarábik, who is in Istanbul, but is frequently in Ukraine, and is based in Vilnius for us. We have Dmitri Trenin on the line from Moscow, and we have Andrew Weiss, director of our program, who’s also on the line.

So this is an on-the-record call. It’s 30 minutes long, and when you ask a question I would just ask you to identify yourselves so that everyone knows where the question is coming from. Maybe we just start with you, Balázs, as you’re kind of nearest to the scene and have been in Ukraine recently.

We’ve got the V-E Day celebrations coming up on May 9th. Could you give us a sense of what you think might happen there, and what the referenda, if the separatists do hold the referendum, is likely to do a few days later?

BALAZS JARABIK: Well, I thank you for having me here. Obviously, this is a very important week for Ukraine because of the two events on May 9 and May 11. I think there is a lot of worry most about May 9, the Victory Day. I heard there were plans for major rallies in Donetsk, and obviously, the main question is what’s going to happen in Odessa.

TOM CARVER: When you say “worry,” do you have any sense of what form these celebrations might take? I mean are there big celebrations planned in a lot of the cities?

BALAZS JARABIK: Well, there are no official celebrations. Basically, the authorities cancelled all the official celebrations quoting security situations. They said, “We cannot guarantee the security of our citizens in the current circumstances.” Obviously, these are going to be the pro-Russian forces who are going to rally, at least what I’m hearing from local sources, and then probably there could be provocations and it’s going to be pretty much, and what we had been seeing a few days ago, the tragic events in Odessa.

These provocations are very easy to foment. You know, there’s a lot of _________ engaged. It’s in office. One of the _______ authorities should, and basically an open conflict. It’s going to break up what we’ve seen in Odessa. So, basically, a lot of ______ here. That’s a scene that’s tragic even to Odessa may happen in the East, and as well in the site itself.

TOM CARVER: Dmitri, the elections that are still on, at least at the moment, for May 25th, what’s your sense of how the Russian government is going to respond to them? Do you think that they will in any way recognize the outcome of them or not?

DMITRI TRENIN: Well, my take is that the Russian government is pretty skeptical about the presidential election on May 25. They referred to the violence that you see in Odessa. They refer to the “anti-terrorist operation” in Eastern Ukraine, and they’ve also referred to the referendum that are called in Lugansk and Donetsk on self-determination or autonomy of those regions.

Interestingly enough, I haven’t seen questions of the referendum, but the Russian media does not refer to either of the two referenda as deciding whether those regions want to join Russia or not. This is not the question that’s being discussed or even mentioned in Russia.

But on the other hand, I would say that the Kremlin is still holding the door open. Mr. Labrov, in his public remarks yesterday in Vienna at the Council of Europe, said that, “We will look at the results. We will look at the atmosphere surrounding the elections before we pronounce our own judgment on that.”

It’s very interesting also that the Russian Parliament is not sending observers to the referenda in Ukraine. Very important in my view, and thirdly, President Putin has just met with the acting chairman of the OSCE, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, who is president of Switzerland, today in Moscow.

So as I understand from diplomatic sources, there’s heightened diplomatic activity. Mr. Labrov met with the German Foreign Minister while in Vienna. Steinmeier has also come up with an article in the ___________ about the ways out of the situation. They talk about potentially holding another meeting in Geneva as early as next week. So there’s a frenzy of diplomatic activity as well. I think I would stop here.

TOM CARVER: You know, if what Balázs says comes to pass and there is a lot of violence on these V-E Day celebrations, do you see Moscow moving in in any way across the border? I mean at what level does it require for them to intervene?

DMITRI TRENIN: Well, I think, to me, I pray to be excused. The idea of Russia sending forces into Ukraine has always looked fairly incredible to me at this point, ever since the beginning of this present crisis. I believe that the Russian leadership fully understands the consequences of that decision, and it will not be taken lightly.

The idea, I think, that the Russians are fomenting trouble in Eastern Ukraine or elsewhere in order to create a pretext for intervention essentially gives lower marks to the Russians’ ability to calculate things. So I do not expect it either on May 9 or at any moment before the elections.

Again, we have to be very clear minded and realistic about the potential future scenarios. There may be a scenario of a full-blown civil war in Ukraine. We’re not there yet. We’re still far away from that, hoping it will never come to pass as that scenario would draw Russia _______, but at this point Russia is not, in my view, in my analysis, not about to intervene militarily in Ukraine.

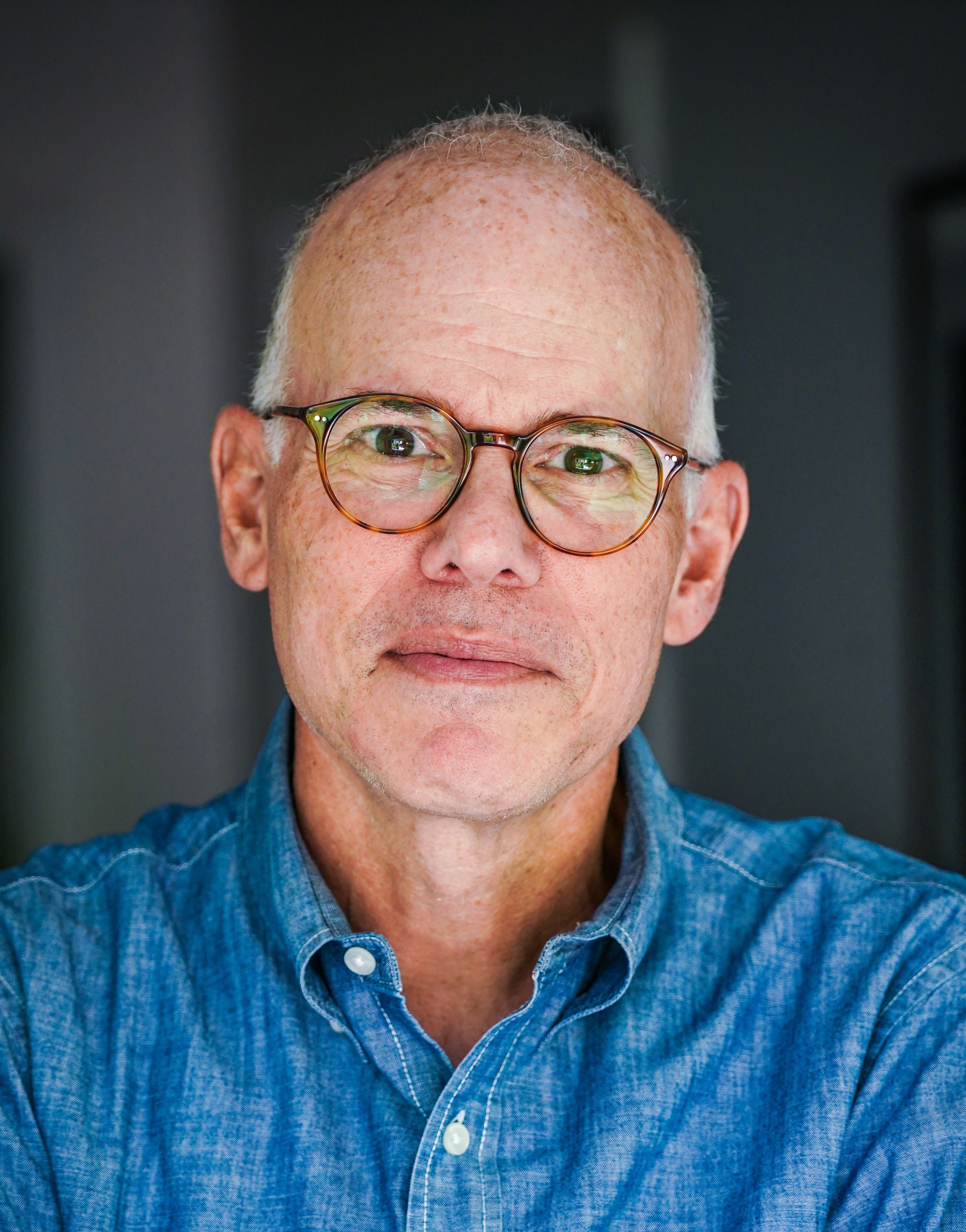

TOM CARVER: Okay. Andrew, you’ve just come in. You’ve just written this article for the New Republic criticizing Obama’s position. Do you want to just elaborate on that and give us your thoughts about why they’re on the wrong track?

ANDREW WEISS: Well, I don’t know if I’d say they’re on the wrong track. I’d say that what we’ve got, though, is a decisive moment in the West’s response to the crisis, and it’s striking if you listen to the different words coming out from the Obama administration. The focus really is let’s try to deter Russia from what Dmitri is describing as probably a remote policy option, and try to basically say that everything that’s happening in Eastern Ukraine or Southern Ukraine bears on some level Russian authorship.

What I think is missing in the current strategy are sort of two issues: One is the scale of the disruption in the East. There’s lots of actors now. There’s lots of people with guns, both pro-Kiev and pro-Moscow, running around. So I see a lot more scope for escalation and miscalculation. And two, I’m concerned that the portrayal of unity between the Western camp, within and among the Western camp, is perhaps misleading.

On Friday you had President Obama and Chancellor Merkel talking about how if Russia disrupts the May 25th elections, that will trigger some form of sectorial sanctions. They’ve left undefined exactly what sectorial sanctions are, and we can talk about that in a discussion.

And then yesterday when the President and Secretary Kerry met separately with Lady Ashton, you heard sort of a discussion about sanctions. The words “sectorial sanctions” wasn’t mentioned.

There’s a Foreign Policy Council meeting in Brussels on Monday, but again, there’s just huge gaps between reality and rhetoric here, which I think it’s going to be very hard for all 28 EU members to come around sanctions’ proposals that would look similar to what Washington would want, and the effort to sort of put pressure on Russia in the end, I think, is going to find itself wanting. There’s just not as much unity and appetite for confrontation with Moscow at the moment.

And again, I think, you know, ultimately the Russians have a lot of arrows in the quiver and a lot of room for maneuver here. I’m not sure if time is on the West side.

DMITRI TRENIN: Okay. Let’s open it up to questions for Balázs or Dmitri or Andrew. Anyone what to start?

PETER KENYON: Hi. This is Peter Kenyon from NPR. I didn’t realize, Balázs, you were in Istanbul. So am I. Hello. And I just wanted to ask: On the 25th election for the Ukrainian government, what is your assessment of how likely this is to be received as something legitimate, something that gains momentum and gives them some kind of authority and legitimacy? And what will it take to achieve that result?

BALAZS JARABIK: Well, based on the latest polling results, you know, the Ukrainians are actually expecting across the country, even in the East, the turnout that I was seeing in the polling, but even in the East, including Donetsk ______, I mean the turnout of people who expressed their willingness to go to was around 70 percent. Now across the country it was 84 percent. That was obviously a good three or four weeks ago so it’s a question how the current events are obviously negatively influencing that.

In a security situation in general the authorities can ensure the people that this is going to be, you know, security come out of the vote as the major question.

Now those who I have been talking to, and even when I was in Kiev, you know the actual security situation doesn’t appear that much a threat or a risk as it appears for outsiders. Even when I’m leaving Kiev it always strikes me how the difference between when I am there and when I’m out of the country, and it’s really a reasonable psychological difference. So let’s keep that mind.

So I think the turnout is going to be high. It’s more the question is what’s going to happen in the East and whether the _____ can actually organize it and ensure the security in the East. I don’t think it’s going to be a problem in Odessa, for example, but, you know, this change in the governorship and the relationship with the police, the problem between the governor and the police is going to be key, and the Central Election Commission and the local election commissions are going to be key.

So the question is how much the separatists can control, how much they can destruct, I think this is a clear strategy and a clear goal, and this is why the Ukraine governments are trying to clean – or at least keep the separatists in check by the anti-terrorist operation.

TOM CARVER: Okay. Anyone else?

MICHAEL PETROU: Sure. It’s Michael Petrou here from Maclean’s magazine. Dmitri, you said that you had predicted in a civil war situation that might be aligned, it would draw Russia into Ukraine, presumably in moreover ways than it’s there already. I’m just wondering if yourself or the other two panelists can envision the situation in which Ukraine’s Western allies might similarly feel compelled to get involved militarily. Is that an outcome that’s likely or even possible?

DMITRI TRENIN: Well, I think, Michael, that civil wars in the area, unfortunately, is possible, and the events in Odessa are in that sense telling in terms of how developments might proceed without anyone actually designing or planning for the next stage, but the situation could just deteriorate beyond a certain point – a point of no return.

The thing is that when you watch television in Moscow with extensive coverage of developments in Ukraine, you very quickly form the idea that everyone on television, whether they are on the Kiev side or Moscow side, looks and sounds precisely as people in your own country, Russia.

It’s still 20-plus years after the fall of the Soviet Union, there’s still evidence to support this claim that Mr. Putin often makes that Russians and Ukrainians are basically one people. Of course, a clear distinction between most Ukrainians and Western Ukrainians.

So if something happens in Ukraine that leads to a civil war, I find, because of the many links that exist, because of the huge interest that exists here in the developments in Ukraine because of the public pressure that might arise, I see ways in which Russia could be actually more of an active participant in what’s going on in Ukraine.

Right now you kind of believe that there is a Russian involvement, Russian presence. I think if you talk to the Russians they will tell you about Western participants and Western presence, but it’s very clear that most of the people we’ve seen acting now are very much Ukrainians. At some point, as I said, if there is full-scale fighting, if larger portions of the population turn against other big portions of the population, I believe that Putin will be compelled, if you like, by the developments on the ground to use the powers that he has from the Russian Parliament to move militarily into Ukraine.

However, I understand that the consequences of such a move are very clear, and should be very clear to the Russian leadership. It’s nothing less than having an Eastern European version of Afghanistan, an open-ended involvement, which basically could have tremendous consequences for your own country in the end.

So, as I said, any decisional back move, to take it very carefully. It’s not an expeditionary operation. It’s not a U.S. President deciding on an involvement in the Middle East or in the Balkans. It’s very close. It’s next door, and ______, as I said, in many ways still the old Soviet-administrative line so any decision about that is going to be extremely difficult, but extremely important if at stake.

MICHAEL PETROU: Do you see Ukraine’s Western allies making any similar decision in intervening militarily were this to escalate into civil war?

DMITRI TRENIN: It’s difficult for me to talk about the West, but I would imagine the West not becoming involved with boots on the ground, but I can imagine the West helping Ukraine militarily and becoming pretty much involved with advisors and military hardware, which in the Russian eyes will make the West a participant in the conflict. And if you imagine Russian soldiers being killed with weapons supplied by the West and operated by people, Ukrainian military people advised or even ordered by the West as the Russians would see it, there will be an urge on the Russian side to be in kind, to respond in kind, and that could lead to the widening of the conflict.

ANDREW WEISS: It’s Andrew here. Could I just tag onto that? I probably am a little more skeptical about the Western appetite for any form of military involvement in the situation. There have been a lot of, you know, suggestions floating around about various types of lethal assistance, and the U.S. administration has been extremely wary of those.

You know, ultimately Ukraine has a lot of military hardware on its territory, literally millions upon millions of AK-47s and other sort of light weapons and heavy weapons that could be used in response to some worsening of the situation and some type of military confrontation with Russia.

Ultimately, though, the West’s ability to make a decisive impact, I think, it’s hard for me to see that being the case, and I see the risks of escalation as something that will militate towards caution. You know, I mean ultimately NATO is an organization that operates by consensus, and I just can’t see NATO governments coming together on behalf of some form of actual military operations or activity on Ukrainian territory.

JOURNALIST: I’m _____ ______ from Voice of America, Russian ______. May I ask all speakers: What do you think? We have an extremely dangerous situation in Eastern Ukraine right now. The situation was pre-arranged by Russia. Any special plans to create such a mess, or situation went without any control? The conflict _____ from self you to organization or ______ society or something else. What’s the main reason of this mess?

TOM CARVER: Balázs, do you want to have a go at that?

BALAZS JARABIK: Yeah, sure. It’s the hardest question. Thank you. A few things: What we see now, and I think there are enough credible reports from the ground that there are not really Russian troops operating in Eastern Ukraine. Obviously Russia –

Also, the second thing is that Russia has a clear objective, and that’s federalization. Now Russia is the only one who is having the clear objective. Both the West in Ukraine is very much divided, and especially, particularly Ukraine, if you look, the young and the better-educated people of the population, wants the new Ukraine, a European one. The old one wants Russian-level penchant, you know, and the political lead wants business as usual, largely. Right? So there is no consensus within Ukraine, and you see the similar, no consensus in the West what exactly to do in the Ukraine.

Compared to that Russia has a clear objective. Now it may look like Russia is actually working very actively to achieve that clear objective, which is federalization of the country, you know, and Russian obviously has enabling factors – troops at the border, which I consider – I’m an Hungarian from Slovakia – and I consider that how much this, the Russian troops on the border are very close, to provide protection, is it actually an attack on the dual identity of the Ukrainians or the Russians or the pro-Russians of Ukraine? You know, these dual identities down in Russia and Ukraine is falling apart. It’s a very important factor.

The other enabling factor is assistance for separatists, obviously. I already mentioned the Russian-level penchant is a promise, a counter-promise over the European living standards, which the other Ukraine is operating. So these are very important enabling factors, but I myself don’t think that there was a plan in advance. I pretty much see Crimea and everything else is a reaction of what is happening in Ukraine, which clearly is a breakdown of the central authority by the ______ events and what was happening with _______ ______.

TOM CARVER: Okay. Anyone else?

TRUDY RUBIN: Hello?

TOM CARVER: Hi.

TRUDY RUBIN: Trudy Rubin from the Philadelphia Inquirer. Can you hear me?

TOM CARVER: Yeah. We can hear you fine.

TRUDY RUBIN: Okay. I wanted to ask Dmitri or all of you, following on the last question, do you think Russia wants permanent destabilization if it cannot get a constitutional amendment that decentralizes the country to the point where it effectively can control provinces in the east and the south? What does Putin want?

[Laughter]

DMITRI TRENIN: Trudy, I think that if Ukraine does not find a way to balance its many interests, its many regions, its many age groups, its many vectors, it will be a prominently unstable country whether Russia is involved or not. I’m not talking about the particular form that this would need to take, but some kind of an all-Ukrainian compromise, an all-Ukrainian agreement on what constitutes the underpinnings of this new Ukrainian state, because the previous Ukrainian state could only survive as long as it was not moving anywhere. It started to move in February and it collapsed. It needs more prominent underpinnings than the remnants of the Soviet Republic of Ukraine, which I think we’ve been living with until last February. So I think that something along the lines of a national consensus is absolutely necessary.

I don’t think that Russia is interested in prominent destabilization for the sake of prominently stabilization. I think that they understand the dangers of that for themselves, but also because – I think Balázs made that point, the developments in Eastern Ukraine, they may be supported, the Russians may sympathize with them, whatever, but in many ways what you see in Eastern Ukraine is an Eastern Ukrainian product, and to present the narrative that it’s all the work of Russian saboteurs or Russian agents, I think, is self-defeating in terms of the future composition, the future stability of Ukraine.

TRUDY RUBIN: If I could just follow up on that, but it seems clear from polls that in Eastern Ukraine they do not want to be part of Russia. They’re just nervous. If you Ukraine were left to itself, perhaps it could find this consensus, but it seems that the consensus that Putin wants is one where at least large parts of Ukraine are totally under Russia’s sway, not Finland.

Do you think that Putin would be satisfied with a formula where Ukraine was neither East nor West? Where it could have a close association with the EU? Or does he want something more totally under his sway, like the post-Soviet federation that he’s looking for?

DMITRI TRENIN: Well, the post-Soviet federation that he’s looking for is not in any way a new edition of the Soviet Union or anything like that. You talk to the Kazakhstanis, to the Kazakhs, and they will tell you that they don’t want to be part of any empire. They don’t see themselves as being under Russian control, and they are not. You talk to Mr. Lukashenko in Belarus next door, and he will tell you that he doesn’t want Belarus to be under anyone’s thumb, and he is using the present crisis to extract more concessions from Mr. Putin.

So there’s a certain limit to how much sway Russia can have even if they wanted to have it in the neighborhood. Now Ukraine is bigger than Belarus and Kazakhstan combined, and much more nationalistic and much better connected to the Western world.

I think what Mr. Putin wants is a Ukraine that is neutral in terms of its affiliations – NATO, EU and the equivalent institutions led by Russia. He also wants a Ukraine, and that’s very important. That would allow a large part of its people to keep their Russian language and sort of dual identity that has been mentioned here, that people would still allowed to feel whatever, some kind of an affinity toward Russian things, and maybe not the Russian Federation in particular, but, you know, historical Russia, what have you.

Again, he sees those ______ Ukrainians very much as part of the same world as the Russians themselves. And finally, I think he is pushing for federalization in order to be able to create a new Ukrainian elite or provide a new element to the Ukrainian elite to balance the Ukraine elite, which is in many ways people in Kiev who, for very good reasons, to be Ukrainian means to be non-Russian.

Otherwise, if you embrace in Ukraine – the problem in Ukraine, as I see it, and I’m not an expert clearly. Balázs may tell me how wrong I am, but I think that from a Ukrainian perspective, to close integration with Russia would mean brutifying yourself. That would mean turning Ukraine into in many ways a province of Russia on equal terms with the rest of the Russian Federation, but still within this Russian world that Mr. Putin is talking about.

TOM CARVER: Okay. Well, we’re overtime, in fact, so I think we will call a halt there. We all obviously watch these developments very closely – the V-E Day and the referenda, if they happen on the 11th, and we will be back in touch I’m sure next week with a call of some kind.

So the transcript for this will be available tomorrow, and, obviously, if you want to get hold of either Balázs or Dmitri or Andrew, then please feel free to contact them or contact Clara directly, but that’s it for the call. Thank you for participating