No other part of the world admires Lee Kuan Yew as much as the authoritarian post-Soviet states. In justifying restrictions on the media and crackdowns on the opposition, post-Soviet leaders frequently allude to building the “Singaporean model.” However, Lee himself believed that resource-based dictatorships will fail to replicate Singapore’s success, since restricting freedoms is not the cornerstone of his model.

If a monument to Lee Kuan Yew is to be erected any time soon, it might very well happen in one of the post-Soviet states. In fact, such attempts have been made in the past—the Kaluga governor wanted to put a statue of the Singaporean reformer right in the center of the region’s capital. Officials in Tatarstan were reportedly interested in erecting such a monument as well. The national leaders also heaped praise on Lee. While speaking to his inner circle, Dmitry Medvedev loved to mention being counseled by the legendary prime minister. Reacting to the news of Lee Kuan Yew’s death, Vladimir Putin’s Press Secretary, Dmitry Peskov, publically stated that the Russian president highly valued his contacts with Lee, who even reprimanded Putin on his excessively liberal economic agenda. Finally, the economic minister and later Sberbank president, German Gref, was one of the main enthusiasts of the Singaporean model.

Why do all of these people value Lee Kuan Yew so much? The post-Soviet elites’ peculiar understanding of the essence of the Singaporean model provides an answer. They use the system that Lee constructed in Singapore to justify political crackdown. The “Singaporean miracle” is generally reduced to successful state-run capitalism and a dictatorship in which a personalized-power regime and restrictions on freedoms are the price to pay for economic development. One doesn’t have to engage in institution-building—it is enough to consolidate power and micromanage everything.

The proponents of this approach are in effect saying, “You want Singaporean skyscrapers? Put up with the decades-long rule by the same individual, media censorship, and selective repressions against the opposition.” This logic implies that people will have to put up with this state of affairs for quite some time, since Lee Kuan Yew was in power for over thirty years. By tracing their political genesis to Lee, the post-Soviet rulers are justifying the lack of alternatives to their own regimes. The only aspect in which they differ is his fight against corruption. Some leaders (especially the leaders of resource-poor regions) prefer to focus on Lee’s quote: “Put three friends behind bars, and both you and they will know what for.” Others believe that Lee propounded fighting corruption among the lower ranks and rewarding friends and relatives on the top. After all, he left his son to run the country; his wife runs the Temasek Foundation, and his other family members play prominent roles in the Singaporean economy.

For his part, Lee Kuan Yew never refused to meet post-Soviet leaders—the old man was generally curious and didn’t limit himself to meeting just the nice guys. But in his private conversations with experts, he was always insisting that the models these people are constructing in their countries have nothing to do with his. He is certainly right. The city-state, which completely lacks natural resources and imports even water, would simply be unable to sustain the level of inefficiency retained by the post-Soviet authoritarian regimes that are hiding behind the talk of the Singaporean model.

Throughout his life, Lee invested in the only resource his country had (apart from its convenient location)—the people. But this is exactly the resource that all post- Soviet rulers continue to ignore. In Singapore, corporal punishment, fines for spitting and littering, and the censorship of the media and arts coexisted with an emphasis on education, the imposition of the English language and subsequently standard Chinese, lessons on proper decorum, and sending the most talented students to the most prestigious international universities. This is in fact the essence of the Singaporean model.

In educating his fellow citizens, Lee Kuan Yew didn’t just act as a Confucian paternalist; he also was a despotic teacher with a whip—his last official title of “Minister Mentor” is a very apt description of his management style. Lee Kuan Yew was not a humanist who took care of people for their own sake. He treated people as a head of a corporation would treat his workforce by constantly keeping it prepared for the fast-changing competitive environment. The same applies to fighting corruption. Lee’s policy of stiff penalties and generous rewards for good work, which made corruption risky and illogical, served to lower business transaction costs and made Singapore an ideal venue for international investments in Southeast Asia. This was one of the reasons behind Lee Kuan Yew’s retirement after handing the country over to one of the most professional management teams in the world. After all, he had no resource revenues to conceal inefficiency.

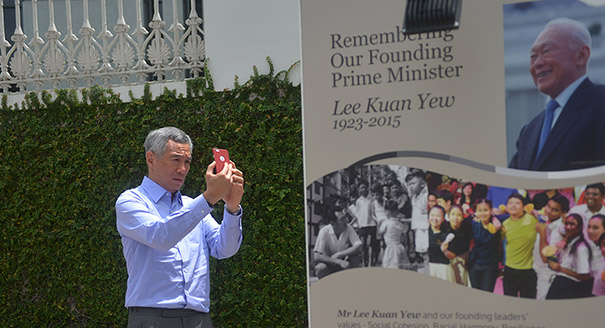

One can argue with how right Lee Kuan Yew’s approach to Singapore’s population was and disagree over whether the “right” choice from the top is better than the test of freedom. But anyone who dealt with Singaporeans—be it government officials, businesspeople, or scientists—will testify to their global thinking, incredible work ethic, and determination. The late Lee Kuan Yew, in fact, possessed all these traits. Thus, the people he left behind will be a better monument to him than any of the monuments planned by his self-proclaimed disciples.

This publication originally appeared in Russian.

.jpg)