The countries in the region are managing the fallout from Iranian strikes in a paradoxical way.

Angie Omar

{

"authors": [

"Perry Cammack",

"Daniel Benaim"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Middle East",

"Western Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Foreign Policy",

"Civil Society"

]

}

Source: Getty

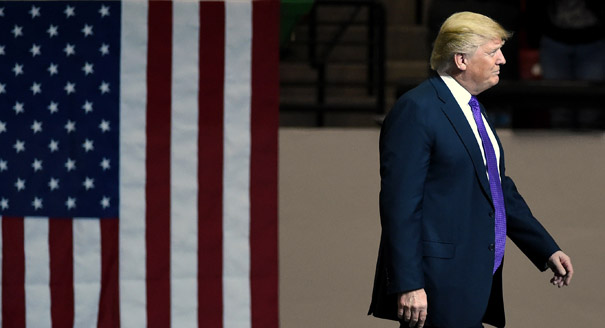

The rise of candidates like Donald Trump is part of a wider global trend spurred by a set of common factors.

Source: New Republic

As tensions over Donald Trump’s political ascendency boil over into violence, many are wondering how a narcissistic, authoritarian-leaning demagogue has secured the inside track to becoming a major party’s nominee for president of the United States.

Much of the commentary has focused on Trump’s character and the historic moment in American political life that has given rise to his candidacy. But while Trump himself may be unique—and distinctly American—Trumpism and the politics of alienation he represents are not. In fact, most of the forces fueling Trump’s rise are already wreaking political havoc around the world—including in a Europe buffeted by its own volatile mix of institutional malaise, economic stagnation, and demographic change.In fact, we may be seeing the beginning of significant international changes that could inject chaos into global politics for years to come. A preview of this fall’s National Intelligence Council Global Trends report released last week suggested that discontent with existing societal bargains and government policies will go global—roiling politics in America’s partners and adversaries alike.

Across Europe, we are seeing hyper-nationalist figures emerge with several common features. They demonize minorities, immigrants, and gays and lesbians, and express nostalgia for a simpler (read: less diverse, less democratic) time. They vilify conventional politicians as feckless and political opponents as traitors. They celebrate the crushing of dissent and flirt with violence. They play on nativist rejections of European unity, NATO, and other transnational projects that underpin the liberal international order and that have done so much in the last half-century to promote stability in Europe and lift hundreds of millions out of poverty worldwide.

In a country of relatively strong and enduring institutions like the United States, the politics of alienation can lead to Donald Trump, whose likely high-water mark will be the Republican nomination. Where modern democratic institutions run less deep, the results can be even worse.

In Hungary, for example, Prime Minister Viktor Orban has described his country as an “illiberal state,” and the anti-Semitic Jobbik party is the country’s third-largest. In Slovakia, neo-Nazis were recently elected to the parliament. In Greece, the Golden Dawn party, which makes use of Nazi symbolism, commands a sizable parliamentary bloc.

As Trump demonstrates, it’s not just so-called emerging democracies that are flirting with extremism. Front National leader Marine La Pen, a plausible contender to become the next president of France, has vowed to pull her country out of NATO and the European Union. In Germany, England, and elsewhere, political fortunes have risen for actors who until recently were considered beyond the pale, but are now speaking for alienated groups.

The standard-bearer and patron of this phenomenon is Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has paired his brand of hyper-macho contempt for liberalism with active support for radical parties in Europe. It should come as no surprise that Putin has lavishly praised Trump, who returned the favor by whitewashing Putin’s “alleged” murder of journalists by declaring, “I think our country does plenty of killing, too.” Putin presents a superficially appealing model, having quashed domestic dissent and made tactical gains in Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine. Over the longer run, his approach looks like a loser, since cronyism will cannibalize Russia’s economic potential and his supposed foreign policy successes will further alienate his neighbors and open Russia to punitive sanctions.

Still, the politics of alienation isn’t going away anytime soon. How did it take root in so many places at once?

We see four principal factors at work, working both globally and locally.

First is the worldwide acceleration of economic inequality, propelled by globalization. In America, six straight years of positive job creation has reduced the unemployment rate in half to under 5 percent, and the U.S. is in a relatively strong macroeconomic position compared to other advanced economies. But for many Americans, it doesn’t feel that way. The middle class is shrinking, income has been largely stagnant for decades, manufacturing has been gutted, and the wealthiest 1 percent have captured the vast majority of America’s economic recovery.

The picture in Europe is even gloomier. With high structural unemployment and a rapidly aging population, European economic growth was anemic even before the 2008 financial crisis and crippling austerity measures that followed. The EU’s share of global economic output is falling. Beyond Europe’s borders, in rentier states like Russia and much of the Middle East, the sustained downturn in oil prices could devastate already fragile and beleaguered middle classes.

Second is the disruptive impact of information technology and social communication, which seem likely to rewrite the rules of politics everywhere except possibly North Korea. Even as large swaths of the populations in America and Europe feel alienated from their institutions of government, they are also increasingly less dependent on elites for information, access, guidance, or platforms.

Third is the demographic change that, though playing out differently in America and Europe, stokes similar cultural anxieties. Both continents look different than they used to. In the United States, this is not simply reflected in the election of the first African-American president in 2008: By 2020, more than half of the nation’s children are projected to be nonwhite. And while the recent net flow of people across the Untied States’s southern border has been toward Mexico, America’s 55 million Hispanics represent a growing share of the population and workforce.

If these circumstances prove challenging for a country that prides itself as a nation of immigrants, imagine the impact in Europe, where societies have defined themselves for centuries in terms of national identities. Immigration and culture have long been difficult political issues in Europe, especially since almost every country is failing to produce enough native-born children to sustain its population. But the influx of more than a million refugees in 2015 alone—mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, and with no end in sight—has created a sense of panic that is undermining not only Europe’s ability to marshal a collective response to the problem, but the political standing of important U.S. partners like Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Fourth is the brittleness of the political institutions of many developed nations. As Moises Naim notes in The End of Power, at the same time that economic power has been consolidating, instruments of political power have been collapsing. Most political institutions, whether in the United States or Europe, are proving slow-footed and unresponsive in the face of rapidly changing global events—and austerity has only further hurt their credibility. In America, the failures of the media, political parties, Congress, and even cultural institutions helped pave way for the rise of Occupy Wall Street, the Tea Party movement, and now the groundswell of support for Donald Trump.

A decade ago, Trump would have needed to co-opt the Republican establishment, or contemplate a third-party run. But after having spent seven years trying to manipulate nativist anti-Obama fears through talk radio, the birther movement, and the Tea Party, the Republican establishment now finds itself victim of the same forces, as Donald Trump uses mistrust of “the establishment” and a profusion of tweets to execute a hostile takeover of the GOP.

Although the Democratic Party has been insulated from such tensions, partly by winning four of the last six presidential elections, liberals should take no solace in the Republican turmoil. The politics of alienation have tended to boost the reactionary right, but the Democratic Party may itself be susceptible to the same tumult if the root causes are left unaddressed.

In Europe, some of the most important projects of the past 70 years are at stake—namely, the NATO alliance and the European Union itself. European leaders eager to help shoulder the burdens of challenges beyond their borders—whether those initiatives are driven by economics, humanitarian concerns, or obligations to allies—are losing ground.

What is to be done?

There is a near-term challenge and a long-term challenge. Donald Trump—disapproved of by two in three Americans—remains a long way from the White House. The short-term challenge is to deal him a decisive defeat and ensure that the next U.S. president is a bulwark against the politics of resentment, rather than its most powerful champion.

The longer-term challenge is a far more daunting one: to come to terms with the economic and institutional dislocations caused by globalization, which are squeezing middle classes around the world and giving nativist populists such as Trump the space to thrive.

Effective responses to the frustrations, mistrust, and grievances of alienated voters will vary from context to context, and inevitably draw on an enormously broad set of tools, from equitable taxation to effective immigration policy to better public diplomacy. Where grievances reflect genuine systemic failures, those in power need to be open to moving past orthodoxies to develop novel policy solutions to economic inequality and other problems, new mechanisms to engage and respond more nimbly to citizens, and reforms to reinvigorate institutions. Just as there are common features of Trumpism, hopefully countries can learn from each other’s experiences in developing effective responses.

Especially vital is a renewed effort to shore up civil society and consolidate constitutional and civic norms in established as well as new democracies. A recent bipartisan letter, signed by 139 foreign policy experts, called for the next U.S. administration to make democracy promotion a priority. We agree, and believe it should be a priority within trans-Atlantic cooperation as well, accounting for the domestic politics of partners and adversaries alike.

Ultimately, though, democracy promotion begins at home. The Trump phenomenon is a reminder that we cannot take the health of our democratic institutions for granted. They cannot be left to run on autopilot. They need to be constantly reinvigorated and protected.

Addressing the roots of the politics of alienation requires smart policies. But it may also require a broader self-examination of the larger social, economic, cultural, and political factors that allow a character so resentful, cruel, and unworthy of the mantle of democratic leadership to emerge as a supposed champion of the dispossessed.

Former Nonresident Fellow, Middle East Program

Perry Cammack was a nonresident fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on long-term regional trends and their implications for American foreign policy.

Daniel Benaim

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The countries in the region are managing the fallout from Iranian strikes in a paradoxical way.

Angie Omar

French President Emmanuel Macron has unveiled his country’s new nuclear doctrine. Are the changes he has made enough to reassure France’s European partners in the current geopolitical context?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

The drone strike on the British air base in Akrotiri brings Europe’s proximity to the conflict in Iran into sharp relief. In the fog of war, old tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean risk being reignited, and regional stakeholders must avoid escalation.

Marc Pierini

In an interview, Hassan Mneimneh discusses the ongoing conflict and the myriad miscalculations characterizing it.

Michael Young

Domestic mobilization, personalized leadership, and nationalism have reshaped India’s global behavior.

Sandra Destradi